Main Body

6 Distribution

Leyland F. Pitt (Simon Fraser University, Canada)

Introduction

The Internet and the Web will radically change distribution. The new medium undermines key assumptions upon which traditional distribution philosophy is based, and in practice renders many conventional channels and intermediaries obsolete.

In simple markets of old, producers of goods or services dealt directly with the consumers of those offerings. In some modern business-to-business markets, suppliers also interact on a face-to-face basis with their customers. However, in most contemporary markets, mass production and mass consumption have caused intermediaries to enter the junction between buyer and seller. These intermediaries have either taken title to the goods or services in their flow from producer to customer, or have, in some way, facilitated this by their specialization in one or more of the functions that have to occur for such movement to occur. These flows of title and functions and the intermediaries who have facilitated them have generally come to be known as distribution channels. For a majority of marketing decision makers, dealing with the channel for their product or service ranks as one of the key marketing quandaries faced. In many cases, despite what the textbooks have suggested, there is frequently no real decision as to who should constitute the channel–rather, it is a question of how best to deal with the incumbent channel. Marketing channel decisions are also critical because they intimately affect all other marketing and overall strategic decisions. Distribution channels generally involve relatively long-term commitments, but if managed effectively over time, they create a key external resource. Small wonder then that they exhibit powerful inertial tendencies, for once they are in place and working well, managers are reluctant to fix what is not broken. We contend that the Web will change distribution like no other environmental force since the industrial revolution. Not only will it modify many of the assumptions on which distribution channel structure is based, in many cases, it will transform and even obliterate channels themselves. In doing so, it will render many intermediaries obsolete, while simultaneously creating new channels and, indeed, new intermediaries.

First, we review some of the rationale for distribution channel structure and identify the key tasks of a distribution channel. Second, we consider the Internet and the Web, and describe three forces that will affect the fundamental functions of distribution channels. This then enables the construction of a technology-distribution function matrix, which we suggest is a powerful tool for managers to use to assess the impact that electronic commerce will have on their channels of distribution. Next, we visit each of the cells in this matrix and present a very brief case of a channel in which the medium is currently affecting distribution directly. Finally, we conclude by identifying some of the long-term effects of technology on distribution channels, and possible avenues for management to explore to minimize the detrimental consequences for their distribution strategies specifically, and for overall corporate strategy in general.

What is the purpose of a distribution strategy?

The purpose of a distribution channel is to make the right quantities of the right product/service available at the right place, at the right time. What has made distribution strategy unique relative to the other marketing mix decisions is that it has been almost entirely dependent on physical location. The old saying among retailers is that the three keys to success are the 3 Ls– Location, Location, Location!

Intermediaries provide economies of distribution by increasing the efficiency of the process. They do this by creating time, place, and possession utility, or what we have referred to simply as right product, right place, right time. Intermediaries in the distribution channel fulfill three basic functions.

- Intermediaries support economies of scope by adjusting the discrepancy of assortments . Producers supply large quantities of a relatively small assortment of products or services, while customers require relatively small quantities of a large assortment of products and services. By performing the functions of sorting and assorting, intermediaries create possession utility through the process of exchange and also create time and place utilities. We refer to these activities as reassortment/sorting, which comprise:

- Sorting which consists of arranging products or services according to class, kind, or size.

- Sorting out which would refine sorting by, for example, grading products or output.

- Accumulation which involves the aggregation of stocks from different suppliers, such as all (or the major) producers of household equipment or book publishers.

- Allocation which is really distribution according to a plan–who will get what the producer(s) produced. This might typically involve an activity such as breaking bulk .

- Assorting which has to do with putting an appropriate package together. Thus, a men’s outfitter might provide an assortment of suitable clothing: shirts, ties, trousers, socks, shoes, and underclothes.

- Intermediaries routinize transactions so that the cost of distribution can be minimized. Because of this routinization, transactions do not need to be bargained on an individual basis, which would tend to be inefficient in most markets. Routinization facilitates exchange by leading to standardization and automation. Standardization of products and services enables comparison and assessment, which in turn abets the production of the most highly valued items. By the standardization of issues, such as lot size, delivery frequency, payment, and communication, a routine is created to make the exchange relationship between buyers and sellers both effective and efficient. In channels where it has been possible to automate activities, the costs of activities such as reordering can be minimized–for example, the automatic placing of an order when inventories reach a certain minimum level. In essence, automation involves machines or systems performing tasks previously performed by humans–thereby eliminating errors and reducing labor costs.

- Intermediaries facilitate the searching processes of both producers and customers by structuring the information essential to both parties. Sellers are searching for buyers and buyers are searching for sellers, and at the simplest level, intermediaries provide a place for these parties to find each other. Searching occurs because of uncertainty. Producers are not positive about customers’ needs and customers cannot be sure that they will be able to satisfy their consumption needs. Intermediaries reduce this uncertainty for both parties.

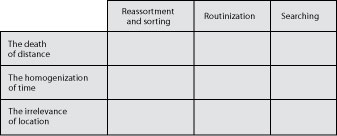

We will use these functions of reassortment/sorting, routinization, and searching in our construction of a technology-distribution function grid, or what we call the Internet Distribution Matrix.

What does technology do?

Understandably at this early stage, the focus has either been on the Web from a general marketing perspective, or as a marketing communication medium. While this attention is important and warranted, less attention has been given to the Web’s impact on distribution channels, and this may turn out to be even more significant than its impact on communication. Indeed, as we shall argue, distribution may in the future change from channels to media. We discern three major effects that electronic commerce will have on distribution. It will kill distance, homogenize time, and make location irrelevant. These effects are now discussed briefly.

The death of distance

In the mid-1960s, an Australian named Geoffrey Blainey wrote a classic study of the impact of geographic isolation on his homeland. He argued that Australia (and, of course, neighbors such as New Zealand) would find it far more difficult to succeed in terms of international trade because of the vast physical distances between the country and world markets. Very recently, Frances Cairncross chose to satirize Blainey’s title, The Tyranny of Distance, by calling her work on the convergence of three technologies (telephone, television, and computer), The Death of Distance. She contends that “distance will no longer determine the cost of communicating electronically.” For the distribution of many products–those that can be digitized, such as pictures, video, sound, and words–distance will thus have no effect on costs. The same is true for services. For all products, distance will have substantially less effect on distribution costs.

The homogenization of time

In the physical market, time and season predominate trading, and therefore by definition, distribution. We see evidence of this in the form of opening hours; activities that occur by time of day and in social and climatic seasonality. The virtual marketplace is atemporal; a Web site is always open. The seller doesn’t need to be awake to serve the buyer and, indeed, the buyer does not have to be awake, or even physically present, to be served by the seller. The Web is independent of season, and it can even be argued that these media create seasonality (such as a Thanksgiving Web browser). Time can thus be homogenized–made uniformly consistent for all buyers and all sellers. Time and distance vanish, and action and response are simultaneous.

The irrelevance of location

Any screen-based activity can be operated anywhere on earth. The Web bookstore Amazon.com, one of the most written about of the new Web-based firms, supplies books to customers who can be located anywhere, from book suppliers who can be located anywhere. The location of Amazon.com matters to neither book buyers nor book publishers. No longer will location be key to most business decisions. We have moved from marketplace to marketspace . To compare marketspace-based firms to their traditional marketplace-based alternatives, one needs to contrast three issues: content (what the buyer purchases), context (the circumstances in which the purchase occurs), and infrastructure (simply what the firm needs in order to do business).

The best way to understand a firm like Amazon.com as a marketspace firm is to simply compare it to a conventional bookstore on the three criteria of content, context, and infrastructure. Conventional bookstores sell books; Amazon.com sells information about books. It offers a vast selection and a delivery system. The interface in a conventional bookstore situation is in a shop with books on the shelves; in the case of Amazon.com, it is through a screen. Conventional bookstores require a shop with shelves, people to serve, a convenient location, and most of all, large stocks of books; Amazon.com requires a fast efficient server and a great database. Try as they might, conventional bookstores can never stock all the books in print; Amazon.com stocks no, or very few, books, but paradoxically, it stocks them all. It really matters where a conventional bookstore is located (convenient location, high traffic, pleasant surroundings); Amazon.com’s location is immaterial. Technology is creating many marketspace firms. In doing so, cynics may observe that it is enacting three new rules of retailing: Location is irrelevant, irrelevant, irrelevant.

The Internet distribution matrix

Contrasting the three effects of technology vertically, with the three basic functions of distribution channels horizontally, permits the construction of a three-by-three grid, which we call the Internet distribution matrix . This is shown in Exhibit 1. We suggest that it can be a powerful tool for managers who wish to identify opportunities for using the Internet and the Web to improve or change distribution strategy. It can also assist in the identification of competitive threats by allowing managers to concentrate on areas where competitors might use technology to perform distribution functions more effectively. Frequently, competition may not be from acknowledged, existing competitors, but from upstarts and from players in entirely different industries.

Each cell in the matrix in permits the identification of an effect of technology on a distribution function. So, for example, the manager is able to ask what effect the death of distance will have on the function of reassortment and sorting, or what effect the irrelevance of location will have on the activity of searching, in his or her firm. In order to stimulate thought in this regard, and to aid vicarious learning, we now offer a number of examples of organizations using their Web sites to exploit the effects of technology on distribution functions. It should be pointed out that neither the technological effects nor the distribution functions are entirely discrete–that is, uniquely identifiable in and of themselves. In other words, it is not possible to say that a particular Web site is only about the death of distance and not about time homogenization, or location irrelevance. Nor is it possible to say that, just because a Web site changes reassortment and sorting, it does not affect routinization and searching. Like most complex organizational phenomena, the forces all interact with each other in reality, and so we have at best succeeded, hopefully, in identifying cases that illustrate interesting best practices, or a good example, in each instance.

The effects of technology on distribution channels

In this section, we move through the cells in the Internet distribution matrix and, in order of sequence, present cases of firms using their Web sites to exploit the effects of technology in changing distribution functions.

The death of distance and reassortment and sorting

Music Maker is a Web site that allows customers anywhere to create CDs of their own by sorting through vast lists of recordings by various artists of every genre. The Web site charges per song, and then allows the customer to also personalize the CD by designing, coloring, and labeling it. The company then presses the CD and delivers it to the customer. Rather than compile a collection of music for the average customer, like a traditional recording company, or attempting to carry an acceptable inventory, like a good conventional record store, Music Maker lets customers do reassortment and sorting for themselves, regardless of how far away they may be from the firm in terms of distance. If a customer wants Beethoven’s “Fifth” and Guns’N’Roses on the same CD, they can have it. At present, distance is only a problem for delivery, and not for reassortment/sorting; however, in the not-too-distant future, even this will not be an impediment. As the costs of digital storage continue to plummet, and as transmission rates increase, customers may simply download the performances they like, rather than have a CD delivered physically, and then press their own CD, or simply store the sound on their hard drive.

The death of distance and routinization

A problem frequently encountered by business-to-business marketers with large product ranges is that of routinely updating their catalogs. This is required in order to accurately reflect the availability of new products and features, changes and modifications to existing products, and of course, price changes. Once the changes have been made, the catalog then needs to be printed, and physically delivered to customers who may be geographically distant, with all the inconvenience and cost that this type of activity incurs. The problem is compounded, of course, by a need for frequent update, product complexity, and the potentially large number of geographically dispersed customers.

DuPont Lubricants markets a large range of lubricants for special applications to customers in many parts of the world. Its catalog has always been subject to change with regard to new products, new applications of existing products, changes to specifications, and price changes. Similarly, GE Plastics, a division of General Electric, offers a large range of plastics with applications in many fields, and the company faced similar problems. Both firms now use virtual routinization by way of their Web sites to replace the physical routinization that updating of printed catalogs required previously. This can be done for customers regardless of distance, and the virtual catalog is, in a real sense, delivered instantaneously. Users are availed of the latest new product descriptions and specifications, and prices, and are also able to search the catalog for the best lubricant or plastic application for a particular job, whichever the case may be.

The death of distance and searching

Anyone who has experienced being a traveler in country A, who wants to purchase an airline ticket to travel from country B to country C, will know the frustration of being at the mercy of travel agents and airlines, both in the home country and also in the other two. Prices of such tickets verged on the extortionate, and the customer was virtually powerless as he or she tried to deal with parties in foreign countries at a distance, unable to shop on the ground (locally) and make the best deal. The German airline Lufthansa’s global reservation system lets travelers book fares from anywhere in the world, to and from anywhere in the world, and permits them to pick up the tickets at the airport. Unlike the Web sites of many airlines, which tend to be dedicated, Lufthansa’s allows the customer to access the timetables, fares, and routes of its competitors. In this way, distance no longer presents an obstacle to customers in their search for need satisfaction, because Lufthansa is able to directly interact with customers all over the world.

The homogenization of time and reassortment/sorting

In a conventional setting, students who wish to complete a degree need to be in class to take the courses they want, and so do the faculty who will present, and the other students who will take, the courses, all at the same time. Where two desired courses clash directly with regard to time slots, or are presented close together at opposite ends of the campus or on different campuses, the student is generally not able to take more than one course at a particular time. This problem is particularly prevalent for many MBA programs with regard to elective courses, and students have to choose among appealing offerings in a way that generally results in satisficing rather than optimizing. Traditional distance learning programs have attempted to overcome these problems but have only been partially successful, for the student misses the live interaction that real-time classes provide. The Global MBA (GEMBA) program of Duke University, Fuqua School of Business, allows its students to take the elective course lectures anywhere, anytime, over the Internet, and uses the medium to permit students to interact with faculty and fellow students. As the on-line brochure states, “Thanks to a unique format that combines multiple international program sites with advanced interactive technologies, GEMBA students can work and live anywhere in the world while participating in the program.” Students enroll for the course from many different parts of the world and in many time zones, yet are now able to self-assort the MBA program that they really want.

The homogenization of time and routinization

Every two months, British Airways mails personalized information to the many millions of members of its frequent flyer Executive Club. The problem is that this information is out-of-date on arrival. When club members wish to redeem miles for free travel, they either have to call the membership desk at the airline to determine the number of available miles, or, more commonly, request a travel agent to do so for them. There is also the problem of determining how far the member can travel on the miles available.

Nowadays, members are availed of on-line, up-to-the minute, and immediate information on their status on the British Airways Web site. By entering a frequent flyer number and a security code, a member is able to get a report on available miles, and check on the latest transactions that have resulted in the earning of miles. Then, the member is presented with a color map of the globe with the city of preferred departure at the center. Other cities to which the member would be able to fly on the available miles are also highlighted. The member is also able do what-if querying of the site by increasing the number of passengers, or upgrading the class of travel. Time is homogenized, and transactions routinized, because members can perform these activities when it suits them, and not have to wait for a mailed report, or for the travel agent’s office to open. What would be a highly customized activity (determining where the member could fly to and how) when performed by humans is reduced to a routine by a system.

The homogenization of time and searching

In many markets, the need to reduce uncertainty by searching is compounded by the problem that buyer and seller operate in different time zones or at different hours of the day or week. Even simple activities, such as routine communication between the parties, become problematic. Employee recruitment presents a good example of these issues–companies search for employees and individuals search for jobs. Both parties in many situations rely on recruitment agencies to enter the channel as intermediaries, not only to simplify their search processes, but also to manage their time (such as, when will it suit the employer to interview, and the employee to be interviewed?).

A number of enterprising sites for recruitment have been set up on the Web. One of these, Monster Board, lists around 50,000 jobs from more than 4,000 companies, including blue-chip employers rated among the best. It keeps potential employees informed by providing customized e-mail updates for job seekers and, of course, potential employers are able to access résumés of suitable candidates on-line, anytime.

The recruitment market also provides excellent examples of getting it wrong and getting it right on the Web as a distribution medium. For many years, the Times Higher Education Supplement has offered the greatest market for jobs in higher education in the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth. Almost all senior, and many lower level, positions in universities and tertiary institutions are advertised in the Times Higher . In 1996, the Times Higher set up a Web site where job seekers could conveniently browse and sort through all the available positions. This must have affected sales of the Times Higher , for within a short while, the Times Higher Web site began to require registration and subscription, perhaps in an attempt to shore up revenues affected by a decline in circulation. Charging, and knowing what to charge for and how, on the Web are issues with which most managers are still grappling. Surfers, perhaps enamored of the fact that most Internet content is free, seem unwilling to pay for information unless it produces real, tangible, immediate, and direct benefits.

Universities in the United Kingdom may have begun to sense that their recruiting was less effective, or someone may have had a bright idea. At the same time as the Times Higher was attempting to charge surfers for access to its jobs pages, a consortium of universities set up a Web site called jobs.ac.uk, to which they all post available positions. Not only is the job seeker able to specify and search by criteria, but once a potential position is found, he or she is able to link directly to the Web site of the institution for further information on issues such as the student body, research, facilities, and faculty–or whatever else the institution has placed on its site. Jobs.ac.uk does not need to be run at a profit, as does the Times Higher . The benefits to the advertising institutions come in the form of reduced job advertising costs and being on a site where job seekers will obviously come to look for positions. This is similar to the way that shoppers reduce their search in the real world by shopping in malls where there is more than one store of the type they intend to patronize.

In traditional markets, where searching requires a physical presence, both buyer and seller need to interact at a mutually suitable time. Of course, this time is not necessarily suitable to the parties in a real sense, and is typically the result of a compromise.

Those who wish to transport large quantities of goods by sea either need to wait until a shipper in another country opens the office before placing a telephone call, or communicate by facsimile and wait for an answer. But what if capacity could be ascertained, and then reserved automatically? And, what if a shipper had spare capacity and wished to sell it urgently? SeaNet is a network that serves the global maritime industry 24 hours a day, regardless of time zones, by facilitating search for buyers and sellers. Reports indicate that this award-winning site is cash positive within a year, and that it experiences subscription renewals at a rate of 90 percent. Shippers can post their open positions, orders, sales, and purchase information onto the site. This information is updated almost instantly and can be accessed by any shipping company anywhere in the world searching the Internet in order to do business–not just subscribers. Companies that want to do business can then contact the seller by e-mail, or by more conventional methods. With the help of SeaNet’s site, shippers can find the information they need quickly and easily.

The irrelevance of location and reassortment/sorting

Conventional computer stores attempt to serve the average customer by offering a range of standard products from computer manufacturers. Manufacturers rely on these intermediaries to inform them about what the typical customer requires, and then produce an average product for this market. Customers travel to the store that is physically near enough to them in order to purchase the product. In this market, location matters. The store must be accessible to customers and, of course, be large enough to carry a reasonable range of goods, as well as provide access and parking to customers.

Dell Computer is one of the real success stories of electronic commerce, with estimates of daily sales off its Web site needing to be updated on a daily basis, and at the time of writing, estimated to be in excess of USD 6 million ( USD 5.5 million) each day. The company has been a sterling performer through the latter half of the 1990s, and much of this recent achievement has been attributed to its trading over the Internet. Using Dell’s Web site, a customer is able to customize a personal computer by specifying (clicking on a range of options) such attributes as processor speed, RAM size, hard drive, CD ROM, and modem type and speed. A handy calculator instantly updates customers on the cost of what they are specifying, so that they can then adjust their budgets accordingly. Once satisfied with a specified package, the customer can place the order and pay on-line. Only then does Dell commence work on the machine, which is delivered to the customer just over a week later. Even more importantly, Dell only places orders for items such as monitors from Sony, or hard drives from Seagate, once the customer’s order is confirmed. The PC industry leader Compaq’s current rate of stock turnover is 12 times per year; Dell’s is 30. This may merely seem like attractive accounting performance until one realizes the tremendous strategic advantage it gives Dell. When Intel launches a new, faster processor, Compaq effectively has to sell six-week-old stock before it is able to launch machines with the new chip. Dell only has to sell ten days’ worth. Dell’s location is irrelevant to customers–the company is where customers want it to be. Dell actually gets the customers to do some work for the company by getting them to do the reassortment and sorting themselves.

The irrelevance of location and routinization

Location has typically been important to the establishment of routines, efforts to standardize, and automation. It is easier and less costly for major buyers to set up purchasing procedures with suppliers who are nearby, if not local, particularly when the purchasing process requires lengthy face-to-face negotiation over issues such as price, quality, and specification. Recent examples of major business-to-business purchasing off Web sites, however, have tended to negate this conventional wisdom.

Caterpillar made its first attempt at serious on-line purchasing on 24 June 1997, when it invited preapproved suppliers to bid on a USD 2.4 million order for hydraulic fittings–simple plastic parts which cost less than a dollar but which can bring a USD 2 million bulldozer to a standstill when they go wrong. Twenty-three suppliers elected to make bids in an on-line process on Caterpillar’s Web site. The first bids came in high, but by lunchtime only nine were still left revising offers. By the time the session closed at the end of the day, the low bid was USD 22 cents. The previous low price paid on the component by Caterpillar had been USD 30 cents . Caterpillar now attains an average saving of 6 percent through its Web site supplier bidding system.

General Electric was one of the first major firms to exploit the Web’s potential in purchasing. In 1996, the firm purchased USD 1 billion worth of goods from 1,400 suppliers over the Internet. As a result, the company reports that the bidding process has been cut from 21 days to 10, and that the cost of goods has declined between 5 and 20 percent. Previously, GE had no foreign suppliers. Now, 15 percent of the company’s suppliers are from outside North America. The company also now encourages suppliers to put their Web pages on GE’s site, and this has been found to effectively attract other business.

The irrelevance of location and searching

Location has in the past been critical to the function of search. Most buyers patronize proximal suppliers because the costs of searching further afield generally outweigh the benefits of a possible lower price. This also creates opportunities for intermediaries to enter the channel. They serve local markets by searching for suppliers on their behalf, while at the same time serving producers by giving them access to more distant and disparate markets. Travel agents and insurance brokers are typical examples of this phenomenon. They search for suitable offerings for customers from a large range of potential suppliers, while at the same time finding customers for these suppliers that the latter would not have been able to reach directly in an economical fashion. The intermediary owns the customer as a result in these situations, and as a result, commands the power in the channel. Interactive marketing enables suppliers to win back power from the channel by interacting directly with the customer, thus learning more about the customer.

The U.K. insurance company Eagle Star now allows customers to obtain quotes on auto insurance directly off its Web site. It offers a 15 percent discount on purchase, and allows credit card payment. The company reports selling 200 policies per month in the first three months of this operation, generating USD 290,000 ( USD 265,000) in premiums, and making 40,000 quotations. While it could be argued that these numbers are minuscule compared to the broker market, it should be remembered that this type of distribution is still in its infancy. Customers may prefer dealing directly with the company, regardless of its or their location, and in doing so, create opportunities for the company to interact with them even further.

Some long-term effects

The long-term effects of the death of distance, homogenization of time, and the irrelevance of location, on the evolution of distribution channels will be manifold and complex to contemplate. However, we comment here on three effects which are already becoming apparent, and which will undoubtedly affect distribution, as we know it in profound ways.

First, we may in the future talk of distribution media rather than distribution channels in the case of most services and many products. A medium can variously be defined as: something, such as an intermediate course of action, that occupies a position or represents a condition midway between extremes; an agency by which something is accomplished, conveyed, or transferred; or a surrounding environment in which something functions and thrives.

Traditionally, distribution channels have been conduits for moving products and services. The effects of the three technological phenomena discussed above will be to move distribution from channels to media. Increasingly in the future, distribution will be through a medium rather than a channel.

The key distinction that we make between a channel and a medium in this context concerns the notion of interactivity. Electronic media such as the Internet are potentially intrinsically interactive. Thus, whereas channels were typically conduits for products, an electronic medium such as the Internet has the potential to go beyond simply passive distribution of products and services, to be an active (and central) creative element in the production of the product or service. From virtual markets (e.g., Priceline.com) through virtual communities (e.g., Firefly) to virtual worlds (e.g., The Palace), the hypermedia of the Web actively constitutes respectively a market, a community, and a virtual world. The medium is thus the central element that allows consumers to co-create a market in the case of Priceline, their own service and produce in the case of Firefly, and their virtual world in the case of ThePalace. Critically, in each instance, the primary relationship is not between customers, but with the mediated environment with which they mutually interact. In summary, McLuhan’s well-known adage that the “medium is the message” can be complemented in the case of interactive electronic medium such as the Web with the addendum that, in some cases, the “medium is the product.”

A second effect of these forces on channel functions may be a rise in commoditization as channels have a diminished effect on the marketer’s ability to differentiate a product or service. Commoditization can be seen as a process by which the complex and the difficult become simple and easy–so simple that anyone can do them, and does. Commoditization may easily be a natural outcome of competition and technological advance, which may see prices plunge and essential differences vanish. Commoditization will be accelerated by the evolution of distribution media that will speed information flow and thus make markets more efficient. The only antidote to commoditization will be to identify a niche market too small to be attractive to others, innovation sufficiently rapid to stay ahead of the pack, or a monopoly. No one needs reminding that the last option is even more difficult to establish than the preceding two.

Disintermediation (and also reintermediation) is the third effect that we discern. As networks connect everybody to everybody else, they increase the opportunities for shortcuts–so that when buyers can connect straight from the computer on their desk to the computer of an insurance company or an airline, insurance brokers and travel agents begin to look slow, inconvenient, and overpriced. In the marketing of products, as opposed to more intangible services, this is also being driven by cheap, convenient, and increasingly universal distribution networks such as FedEx and UPS. No longer does a consumer have to wait for a retailer to open, drive there, attempt to find a salesperson who is generally ill-informed, and then pay over the odds in order to purchase a product, assuming the retailer has the required item in stock. Products and prices can be compared on the Web, and lots of information gleaned. If one supplier is out of stock or more expensive, there is no need to drive miles to a competitor. There are generally many competitors, and all are equidistant, a mere mouse click away. These phenomena will all lead to what has been termed disintermediation, a situation in which traditional intermediaries are squeezed out of channels. As networks turn increasingly mass market, there is a continuous contest of disintermediation (see also the disintermediation threat grid on )

The Web also creates opportunities for reintermediation , where intermediaries may enter channels facilitated electronically. Where this occurs, it will be because they perform one of the three fundamental channel functions of reassortment and sorting, routinization, or searching more effectively than anyone else can. Thus, we are beginning to see new intermediaries set up sites which facilitate simple price search, such as the U.K.-based site Cheapflights, which enables a customer to search for the cheapest flight on a route, and more advanced sites (e.g., Priceline) which actually purchase the cheapest fare when customers state what price they are prepared to pay. In a world where new and unknown brands may have an uphill battle to establish themselves, there may be opportunities for sites set up as honest brokers, merely to validate brands and suppliers on Web sites. In these constant games of disintermediation and reintermediation, customer relationships will be the winners’ prize.

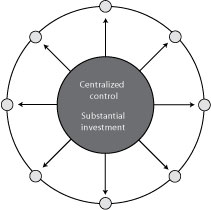

Dealing effectively with distribution issues in the future will require an understanding of the new distribution media, and how the new model will differ from the old. Most extant distribution and communication models are based on centralization, where the investment is at the core and substantially (as shown in Exhibit 2), and considerably lower on the periphery.

In the new model which is shown in Exhibit 3, investment is everywhere, and everywhere quite low. Essentially all that is required is a computer and a telephone line, and anyone can enter the channel. This can be as supplier or customer. Intermediaries can also enter or exit the channel easily; however, their entry and continued existence will still depend on the extent to which they fulfill one or more of the basic functions of distribution. It will also depend on the effects that technology have on distribution in the markets they choose.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have developed the Internet distribution matrix, and suggest that it can be used by existing firms and entrepreneurs to identify at least three things. First, how might the Internet and its multimedia platform, the Web, offer opportunities to perform the existing distribution functions of reassortment/sorting, routinization, and searching more efficiently and effectively. Cases of organizations using the medium to perform these activities, such as those that we have identified, can stimulate thinking. Second, the matrix can enable the identification of competitors poised to use the media to change distribution in the industry and the market. Finally, the matrix may enable managers to brainstorm how an industry can be vulnerable. Neither the firm nor its immediate competitors may be contemplating using the Web to achieve radical change. However, that does not mean that a small startup is not doing so. And the problem with such small startups is that they will not operate in a visible way, or at the same time. In many cases, they might not even take an industry by storm, but they might very well deprive a market of its most valuable customers, as they exploit technology to change the basic functions of distribution.

Cases

Dutta, S., A. De Meyer, and S. Kunduri. 1998. Auto-By-Tel and General Motors: David and Goliath. Fontainebleau, France: INSEAD. ECCH 698-066-1.

Jelassi, T., and H. S. Lai. 1996. CitiusNet: the emergence of a global electronic market. Fontainebleau, France: INSEAD and EAMS. ECCH 696-009-1.

Subirana, B., and M. Zuidhof. 1996. Readers Inn: virtual distribution on the Internet and the transformation of the publishing industry. Barcelona, Spain: IESE. ECCH 196-026-1.

References

Blattberg, R. C., and J. Deighton. 1991. Interactive marketing: exploiting the age of addressability. Sloan Management Review 33 (1):5-14.

Cairncross, Frances. 1997. The death of distance: how the communications revolution will change our lives. London: Orion.

Hoffman, D. L., and T. P. Novak. 1996. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing 60 (July):50-68.

Magretta, Joan. 1998. The power of virtual integration: an interview with Dell Computer’s Michael Dell. Harvard Business Review 76 (2):73-84.

McKenna, Regis. 1997. Real time: preparing for the age of the never satisfied customer. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Quelch, J. A., and L. R. Klein. 1996. The Internet and international marketing. Sloan Management Review 37 (3):60-75.

Stern, Louis W., and Adel I. El-Ansary. 1988. Marketing channels. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.