Health 2: Lifestyle and Choices

Suggested Learning Strategies

Strategies that Focus on Caring

1. Caring and Caregiving Discussion

Invite students, as a whole class or in small groups, to discuss the following questions:

- How is caring about your own health related to being an effective care provider? How do your lifestyle choices reflect your caring for yourself?

- If we truly care for and respect our physical bodies, how will this be reflected in our lifestyle choices?

- How is psychological and emotional health related to the ability to express caring for others?

- How does social connectedness relate to physical and emotional health? What does this tell you in terms of social needs of clients with whom you’ll be working?

- How does cognitive ability relate to overall health? Why is this important for you to understand as you work as a care provider with cognitively challenged individuals?

- In what ways is caring in all its dimensions related to spiritual health?

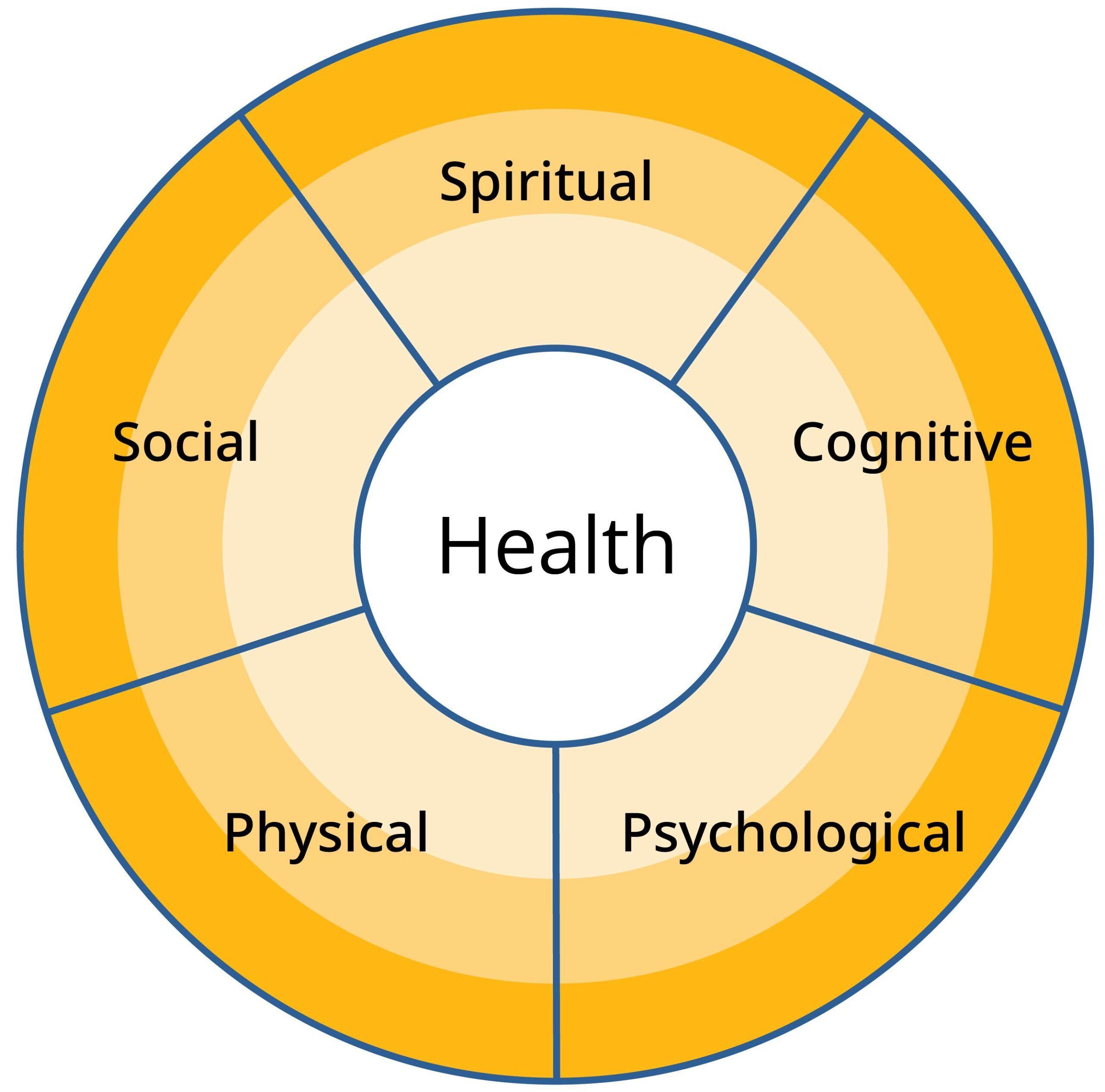

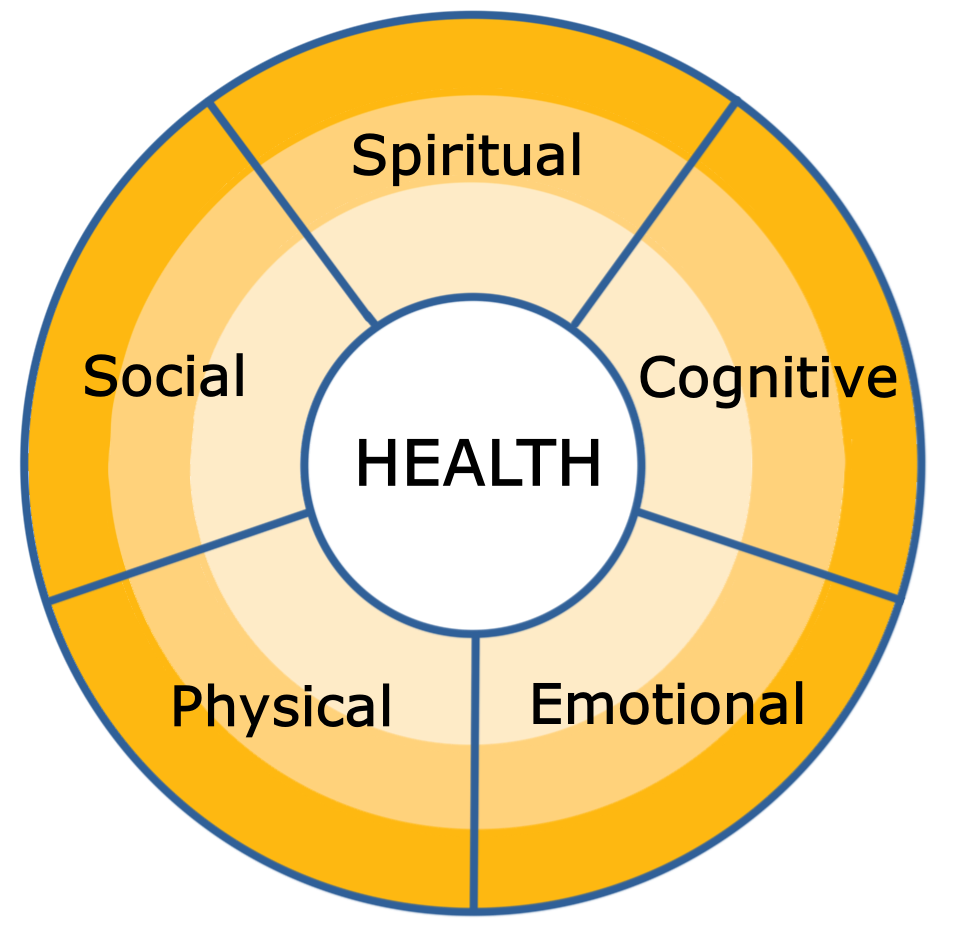

2. Building a Health Wheel

Caring always presupposes a person-centred approach to all caregiving practice. In order to fully understand the uniqueness of each client, students need to grasp how changes in one dimension of health affect and are affected by all the other dimensions. The following exercise helps to portray this interaction:

Begin by drawing a health wheel which identifies the five components or dimensions of health. Encourage students to suggest indicators or signs of health in each of the five components. See diagram below with some suggestions for indicators of health. Another resource is the First Nations Health Authority’s Health Wheel.

The Health Wheel: Indicators of Health

Physical

- Healthy body weight

- Sensory acuity

- Strength and endurance

- Flexibility

- Coordination

- Energy

- Recuperative ability

Psychological

- Ability to cope effectively with the demands of life

- Ability to express emotions appropriately

- Ability to control emotions when necessary

- Possessing feelings of self-worth, self-confidence, and self-esteem

Cognitive

- Ability to process and act on information, clarify values and make sound decisions

- Ability to take in new information and understand new ideas

- Ability to learn from experience

- Ability to solve problems effectively

Spiritual

- Having a sense of unity with one’s environment

- Possessing a guiding sense of meaning and value in life

- Ability to experience love, joy, wonder, and contentment

- Having a sense of purpose and direction in life

Social

- Ability to initiate and maintain satisfying relationships with others

- Knowing how to behave in a variety of social situations

- Having a group of friends and family who care and provide support

- Ability to provide understanding and support to others

3. Exploring the Implications of the Health Wheel

In order to assist students to see the intimate interconnectedness of the five components or dimensions of health, guide the students through the following exercise:

- Identify symptoms or indicators of challenges to health

- Draw a circle around the health wheel and label it “symptoms.” Encourage students to identify symptoms or challenges to health in each of the five dimensions.

- Your question might be: What are physical symptoms or indicators that something is wrong? What are emotional symptoms or indicators? Cognitive? Social? Spiritual? As the students identify these, write them in the circle (see Understanding Holistic Nature of Health below for examples).

- Identify causes of health challenges

- Draw another circle and label it “causes.” Encourage the students to give suggestions for possible causes of health challenges in each dimension.

- Your question might be: What are some physical causes of ill-health? Emotional causes? Cognitive? Social? Spiritual? As the students identify these, write them in the circle (see Understanding Holistic Nature of Health below for examples ).

- NOTE: The causes do not need to match the symptoms.

- Identify behaviours that contribute to health

- Draw a third circle and label it “approaches to health.” Encourage students to give suggestions of behaviours or choices that contribute to health in each dimension.

- Your question might be: What are some behaviours or choices in the physical dimension that contribute to health? In the emotional dimension? Cognitive? Social? Spiritual? As students identify the behaviours, write them in the circle (see below for examples ).

- NOTE: The approaches to health do not need to correspond with the already listed causes or symptoms.

- Examine the interconnectedness of the dimensions

- Choose a student from the group and ask that person to secretly select one of the symptoms and write it down, another to secretly select a cause, a third to secretly select an approach to health and a fourth to secretly select a sign of health. Encourage these students to select from any of the health dimensions.

- Invite the students to reveal their selection by using the following script:

Here’s a situation in which a person is experiencing (symptom), caused by (cause). The approach to health that will be undertaken is (approach to health), and the result, hopefully, will be (sign of health). - Experiment with this exercise two or three times. Since each dimension of health represents a part of a whole, no combination will ever be too far-fetched.

- Invite students to discuss what this exercise has displayed with respect to:

- The degree to which one dimension of health affects every other dimension.

- The degree to which choices or approaches to health in one dimension affect the other dimensions and what this suggests for creative thinking when individuals are searching for remedies or treatments.

- In Canadian society we tend to be more comfortable with the physical dimension of health and most often seek physical treatments for physical symptoms. Is this adequate? Could we be more creative and discover more options?

- How might traditional medicines or alternative treatments contribute to holistic health?

4. Unfolding Case Study: Caring for Peter Schultz

As a homework assignment, have students review their client portfolio for Peter Schultz and the Health Wheel: Indicators of Health. They could also use the First Nations Health Authority’s Health Wheel for this assignment.

- Whole Class Activity and Discussion

- In class, draw a health wheel on the white board, labelling the components (e.g., emotional) and their indicators (e.g., ability to cope effectively with the demands of life), where applicable. Leave the health wheel on the white board for reference throughout the activity.

- Small Group Activity

- Divide the class into small groups, assigning half of the groups to develop a health wheel for Peter and the other half to develop a health wheel for Peter’s wife, Eve.

- Students should use their knowledge about person-centred care, family care providers, and health to identify two to three challenges that may be experienced for each component of health (e.g., for emotional health, caregiver stress is a potential challenge for Eve).

- The students should then identify one or two positive behaviours that could be used to address the challenges identified (e.g., to address caregiver stress, Eve may benefit from attending a support group). If time allows, students could also be directed to identify a resource available online or in the community as support (e.g., Alzheimer Society of B.C. Caregiver Support Group).

- Whole Class Activity Debrief

- Come together as a class and review the health wheels that have been developed. Work together to identify additional challenges and behaviours to support health.

- Note: Students could be instructed to add the completed health wheel to their client portfolio for Peter Schultz.

Understanding Holistic Nature of Health

| Components of Health | Symptoms | Causes | Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical |

|

|

|

| Cognitive |

|

|

|

| Social |

|

|

|

| Emotional |

|

|

|

| Spiritual |

|

|

|

Strategies that Focus on Critical Thinking, Problem-Solving, and Decision-Making

1. Classroom Debate Activity

Invite students to engage in a debate about a topic discussed in this course. Divide the class into small groups of three to five students and assign two groups to each of the topics outlined; one group will take a pro position towards the topic and the other group will take a con position.

Ask each group to identify two to three reasons to support the position they have been assigned. Then, with the instructor acting as the moderator, the two groups will engage in a debate using the following structure:

- Each group provides a brief introduction to their position on the topic.

- In alternating format, the two groups present the two or three reasons identified to support their position.

- Each group provides a brief closing statement.

After the debate has concluded, briefly come together as a larger group and summarize the positions that were presented. Invite feedback from the students not involved in the debate and discuss further considerations. Alternate groups until each student has participated in a debate.

Debate topics for Health 2: Lifestyle and Choices:

- Health care professionals should not smoke.

- HCAs should be required to have vaccinations.

- HCAs who understand health care from a global perspective are able to provide better care for their clients.

2. Determinants of Health – Critical Thinking Exercise

Have students work in small groups. Each group chooses, or is assigned, two to three determinants of health. The groups develop and write down scenarios to illustrate how the multiple determinants of health interrelate and influence health. The groups then share their scenarios with the rest of the class.

3. Evaluating Online Health Information

Health literacy is described by the Canadian Public Health Association as “the ability to access, understand, evaluate, and communicate information as a way to

promote, maintain, and improve health in a variety of settings across the life-course.”[1]

- To support students in accessing reliable health information, ask them to work in pairs to research a health-related topic (e.g., determinants of health, components of health).

- Using the STUDENT HANDOUT below, have the students visit a website related to their topic and complete an evaluation of the information provided.

- After students have completed the exercise, briefly come together as a group to review the online health resources that were evaluated, discussing why it is important for health consumers, HCAs, and students to carefully evaluate health information found online.

- Ask students what other criteria are important to consider when evaluating information online.

This activity could be completed as part of a related assignment, such as the Lifestyle Change Project (Learning Strategy 4) below.

STUDENT HANDOUT

Evaluating Health Information Online: A Checklist

When seeking health information online, it is important to keep in mind that the Internet is not regulated and anyone can set up a website. The criteria presented here will help to decide whether information found online is credible.

- Does the website say who is responsible for the information and how you can contact them? Look for sections called About us, About this site, or Contact us. Be wary if you can’t find out who runs the site and how to contact them.

- Is the purpose of the website to give information, or is it trying to sell you something? Commercial websites (with a URL address ending in .com) might provide information that supports what they are selling and not a balanced view. Be sure that the information presented on the website is suitable for the topic and is consistent with information seen from other sources.

- Does the web address confirm that its scope and/or purpose is suitable? For example, .edu for educational sites, .gov/gc.ca for government sites, .org for non-profit organizations, etc. You can usually get reliable health information from non-profit educational or medical organizations and government agencies. Health information should be unbiased and balanced, based on solid medical evidence, and not just someone’s opinion.

- Does the website give references to articles in medical journals or other sources to back up its health information? The most trustworthy health information is based on medical research. The website should provide links to other resources that can be accessed for information on this topic.

- Is the information provided easy to understand and presented clearly? Technical or unfamiliar terms should be clearly explained.

- Is there evidence that the website is well maintained and does not include misspellings or broken links? Websites should tell you when the information was prepared and updated, and resources and links should be recent.

Note: The material used to create this checklist has been obtained from the following sources:

- Evaluating Information Found on the Internet, Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries. Retrieved from http://guides.library.jhu.edu/content.php?pid=198142&sid=1657518

- Internet Research: Finding and Evaluating Resources, Simon Fraser University Library. Retrieved from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/help/research-assistance/finding-evaluating-resources

Download Student Handout: Evaluating Health Information Online: A Checklist [PDF].

4. Lifestyle Change Project

Invite students to undertake a Lifestyle Change Project, which may be a marked assignment for the course. This assignment will encourage students to actively use an informed problem-solving process to make positive changes in their lives. If possible, have students carry out the change for a period of three to four weeks. This allows time for them to understand the difficulty in sustaining the change, especially during the time of other changes in their lives (e.g., being a student). Students may enjoy using technology to monitor their progress. See Online Learning Tools and Apps at the end of this chapter.

- Assessment: They will be invited to assess their present health status in light of what they have learned in the course.

- Goals: They will set achievable goals related to their assessment.

- Planning: They will be guided to plan carefully for their change project.

- Evaluation: They will be guided to evaluate the effectiveness of their project and reflect on the process.

Students may be invited to form small groups to share their change projects and what was learned.

See the STUDENT HANDOUT to guide this Lifestyle Change Project.

For an alternate assignment, you could use the Planning Your Journey to Wellness: A Road Map from the First Nations Health Authority.

STUDENT HANDOUT

Lifestyle Change Project

The purpose of this project is to provide you with an opportunity to apply knowledge learned in Health 1: Lifestyle and Choices to the development and implementation of a personal lifestyle change process.

- Identify the need for a health-related change or alteration.

- Based on assessments you have done of your current lifestyle choices related to health, what one thing would you like to change or alter?

- What will be the payoffs in making this change or alteration (i.e., why do you want to do it)?

- Set your goal(s).

- When deciding on a goal, remember that it is best to start with small achievable goals rather than big life-changing goals that are more likely to fail. It is much better to have small successes than large failures.

- Write one or two goal statements that describe the behaviour or lifestyle choices you want to change. Phrase your goal(s) in positive language e.g., “I will …”.

- Your goal statement(s) should reflect specific, measurable behaviours rather than general outcomes. For example, “I will go for a 30-minute walk every day” is better than “I will get more exercise.” “I will eat five servings of fruit and vegetables every day” is better than “I will eat more fruits and vegetables.”

- Plan your change process by asking yourself:

- What will I have to give up to make this change or alteration?

- What difficulties or obstacles (habits, thoughts, feelings, attitudes, time demands, inadequate social supports, etc.) are presently holding me back or might be problems in achieving my goal(s)? How might I overcome these obstacles?

- Who are the people in my life who will support me?

- What other ways might I build in support for this change? Are there ways I can reward myself for success? Are there people who might join me in my activities?

- What are the steps in the achievement of my goal(s)?

- How can I make sure that I am recognizing my successes along the way?

- Carry out the change process.

- Set yourself a target date for the achievement of your lifestyle change goal(s) and begin the process.

- Evaluate your experience. In reviewing your experience with the lifestyle change process, discuss:

- Your achievements. Did you meet your goal(s) fully? Partially? Did you have to change your goal(s) as the process progressed?

- Any problems or difficulties encountered in achieving your goal(s). How might these have been avoided or diminished?

- What you learned about lifestyle change from undertaking this project. How might this learning be useful to you in your role as a care provider? What suggestions would you have for others who might want to make changes of a similar kind?

Remember: Even if you aren’t completely successful in meeting your original goal, you will be successful in learning something about yourself and your needs that can be very useful to you in the future as you strive to make health-enhancing lifestyle choices.

© Province of British Columbia. This material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Download Student Handout: Lifestyle Change Project [PDF].

Strategies that Focus on Professional Approaches to Practice

1. Scenarios

Invite students, working in small groups, to review the following scenarios and determine to what degree the HCA is behaving in a professional manner. Have students discuss how self-care relates to professional practice.

Sharon Sandhu is an experienced HCA working for a home support agency. Sharon has struggled with her weight for many years, knowing that the extra 30 pounds she carries could be increasing her chances for high blood pressure, diabetes, and cancer.

One of her elderly clients, Mable Chung, is an outspoken, sometimes brutally honest, 90-year-old who regularly advises Sharon that “there is no excuse for being fat.” One day, after hearing Mable’s comments many times, Sharon responds sharply, “Oh, for goodness sake Mable, get off it. I’m sick of hearing your nagging.”

Marg Thompson is an HCA who works in a special care unit with clients who have dementia. She loves her work but often feels tired and lacking in energy. She knows she would feel better if she could cut back on her smoking and exercise more. She tells herself that she will start exercising next month, or when the weather improves, but somehow she never actually gets started. She also promises to stop smoking every New Year’s but so far, she hasn’t. One day Marg’s supervisor mentions to her that he has noticed her lack of energy, which can seem like apathy. He has also noticed that Marg has had more illness (mainly colds) in the past year than anyone else on the unit. He wonders if she is unhappy with her job and, possibly, should consider working elsewhere.

James Ahmed is an HCA on a surgical unit in an acute care hospital. He works steady afternoon (1500–2300) shifts. This works well for him, as his wife works day shifts, so he can take his children to school and they only need a couple of hours of after-school child care per day. They are saving to buy a house and every penny counts!

This evening, one of the clients who had surgery today is very confused and agitated. The nurse assigns James to do 1:1 observation with the client. James keeps the client safe and reports his observations to the nurse. At the end of the shift, the nurse asks James if he can “do a double” (work until 0700) as the night HCA who was booked for 1:1 phoned in sick. James really needs the money, so decides to accept the shift, even though he only slept a few hours the night before and this is the third double shift he has done this month. James leaves the hospital at 0710 to drive home – a 35-minute drive. He really has trouble keeping his eyes open on the way home.

Suggested Course Assessment

The course learning outcomes may be assessed by the following tasks:

- One or more quizzes or examinations that pertain to knowledge of effective approaches and lifestyle choices that support health (Learning Outcome #2).

- An assignment in which students analyze their personal nutrition level and/or physical activity routines. Invite students to discuss how their choices in nutrition and/or exercise affect all other dimensions of their health (Learning Outcomes #1 and #2).

- A written assignment in which students report on a personal health and lifestyle change process (Learning Outcomes #1, #2, and #3). Students may enjoy tracking their progress using an online tool or app (See Online Learning Tools and Apps for a list of tools).

Resources for Health 2: Lifestyle and Choices

Online Resources

Bergland, C. (2014, March 12). Eight habits that improve cognitive function. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-athletes-way/201403/eight-habits-improve-cognitive-function

Brown University, Health and Wellness. (2015). Alcohol and your body. https://www.brown.edu/campus-life/health/services/promotion/alcohol-other-drugs-alcohol/alcohol-and-your-body

Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. (2013). Understanding substance use: A health promotion perspective. Here to Help. https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/infosheet/understanding-substance-use-a-health-promotion-perspective

Care for Caregivers. (n.d.). Healthcare worker resources. https://www.careforcaregivers.ca/

Emerald Works Mind Tools. (n.d.). Stress management: Manage stress. Be happy and effective at work. https://www.mindtools.com/pages/main/newMN_TCS.htm

First Nations Health Authority (n.d.) First Nations perspective on health and wellness. https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-for-first-nations/first-nations-perspective-on-health-and-wellness

First Nations Health Authority (n.d.) Wellness streams. https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-for-first-nations/wellness-streams

First Nations Health Authority (n.d.) Wellness roadmap. https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-wellness-roadmap.pdf

Government of British Columbia. (2014). Elder abuse reduction curricular resource. BCcampus. http://solr.bccampus.ca:8001/bcc/items/8d5b3363-396e-4749-bf18-0590a75c9e6b/1/

Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Health. (2005). Healthy aging through healthy living: Towards a comprehensive policy and planning framework for seniors in B.C. http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2005/healthy_aging.pdf

Government of Canada, Health Canada. (2016). Eating well with Canada’s food guide. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/index_e.html

Government of Canada, Health Canada. (2012). Environmental and workplace health. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/index-eng.php

Government of Canada, Health Canada. (2015). Food and nutrition. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/index-eng.php

Government of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. (n.d.). Social determinants of health and health inequalities. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html

HealthLinkBC. (2015). Making a change that matters. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/abp2710

HealthLinkBC. (2015). Spirituality and your health. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/abq0372

HealthLinkBC. (2019). Stress management. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/rlxsk#hw153409

Lewis, C. (2019). Why is the wellness wheel important? [Blog post]. https://www.1and1life.com/blog/wellness-wheel/

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Changing your habits for better health. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diet-nutrition/changing-habits-better-health

New York State Department of Health Bureau of Injury Prevention. (2009). Check for safety: A home fall prevention checklist for older adults [Brochure]. https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/0641.pdf

Proactive Mindfulness. (n.d.). Proactive stress management. https://www.proactivemindfulness.com/category/stress/

Simon Fraser University (2014). The 7 dimensions of wellness. http://www.sfu.ca/students/health/resources/wellness/wheel.html

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Health topics. https://www.who.int/health-topics/

WorkSafeBC. (2014, December). Back talk: An owner’s manual for backs. https://www.worksafebc.com/en/resources/health-safety/books-guides/back-talk-an-owners-manual-for-backs

Online Videos

AsapScience. (2014, December 14). Are you sitting too much? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uiKg6JfS658

Alcohol and Drug Foundation. (2014, October 26). Alcohol and your body [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I_OoW_w-uM8

Australian Lions Drug Awareness Foundation, Inc. (2010, August 26). Alcohol and your brain [Video]. YouTube.https://youtu.be/zXjANz9r5F0

Boroson, M. (2011, March 2). One-moment meditation: “How to meditate in a moment” [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/F6eFFCi12v8

Braive. (2017, December 10) Stress bucket [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/1KYC5SsJjx8

Braive. (2016, March 31). The fight flight freeze response [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/jEHwB1PG_-Q

Buettner, D. (2009, September). How to live to be 100+ [Video]. TEDxTC. https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_buettner_how_to_live_to_be_100/up-next?language=en

Government of British Columbia. (n.d.). Move for life DVD [Videos]. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/seniors/health-safety/active-aging/move-for-life-dvd

Maudsley Learning. (2016, July 1). What is mental health? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/G0zJGDokyWQ

McGonigal, K. (2013, June 13). How to make stress your friend [Video]. TEDGlobal. https://www.ted.com/talks/kelly_mcgonigal_how_to_make_stress_your_friend/up-next

MHLiteracy. (2020, May 1). Stress (le stress) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/jHjkEfwfECo

Motivation Thrive. (2021, January 19). I can’t say no! – Don’t be emotionally triggered: Dr.Gabor Maté [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/JKbZbiXzvDg

PE Buddy. (2020, May 10). Learn the 5 dimensions of health! PE Buddy [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijpvLaArBBI&t=11s

PsycheTruth. (2011, August 8). Self-esteem, confidence, how to love yourself, human needs and humanistic psychology [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/hplaY196ARw

TED. (2020, September 2). A walk through the stages of sleep: Sleeping with science, a TED series [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/eM2VWspRpfk

Youngster. (2019, November 6). Top 3 benefits of physical activity: Dr. Greg Wells [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/5-SgF18bCHQ

Online Learning Tools

The following materials are ready for use in the classroom. A brief description and estimated time to complete each activity is included for each.

DocMikeEvans. (2011, December 2). 23 and 1/2 hours. What is the single best thing we can do for our health? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo&list=PL4TcyUrQ3YhJ4X5kajWc

- A video discussing the benefits of daily walking to improve our overall health (15 minutes for viewing and discussion).

Government of Manitoba. (n.d.). Physical education/health education. Module B: Fitness management, lesson 2: Changing physical activity behaviour. https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/physhlth/frame_found_gr11/rm/module_b_lesson_2.pdf

- A lesson outline which applies the Stages of Change model to physical activity. Learning tools and activity suggestions are included (20–30 minutes).

Here to Help. (2016). Wellness modules. http://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/wellness-modules

- A series of 11 modules that address health from a holistic perspective. Modules include discussions of a topic area, self-assessments, and tips for achieving wellness (10–20 minutes per module).

Online Learning Tools and Apps

Anxiety Canada. (n.d.). MindShift CBT [Mobile app]. https://www.anxietycanada.com/resources/mindshift-cbt/

- An app that can be used to identify and apply strategies for dealing with anxiety.

Canadian Mental Health Association. (n.d.). Mental health meter [Mobile app]. http://www.cmha.ca/mental_health/mental-health-meter/

- A mental health self-assessment tool (5–10 minutes).

Healthwise. (2015). Interactive tools. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/tu6657

- A list of tools that can be used to assess health, fitness, and lifestyle (5–10 minutes).

Optimity. (2016). My optimity [Mobile app]. https://www.myoptimity.com/

- An app that can be downloaded to obtain rewards points for improving health-related knowledge (5–10 minutes).

- Canadian Public Health Association. (2017). A Vision for a Health Literate Canada: Report of the Expert Panel of Health Literacy. p. 11. https://www.cpha.ca/vision-health-literate-canada-report-expert-panel-health-literacy ↵