Section 2: Introduction to Sexualized Violence

Section 2 provides background information on sexualized violence including definitions, statistics, and impacts.

You may want to begin by referring to your post-secondary institution’s sexualized violence policy when discussing how we define sexualized violence. The focus of this section is on the cultural, institutional, and environmental factors that are unique to graduate students, influence the likelihood of sexualized violence occurring, and create barriers to a disclosure.

How much time you spend on this section will depend on the participants’ level of knowledge. Participants who have taken previous training in sexualized violence will be more familiar with the concepts and need less time. Other participants who are new to the concepts will require more time.

You could share Handout 1: Supporting Survivors of Sexualized Violence (see Appendix 1: Handouts) after the discussion on the impacts of sexualized violence (slide 11) or you could wait until later in the workshop, after slide 29.

Section 2 includes the following slides:

- Slide 6: How Do We Define Sexualized Violence?

- Slide 7: Sexualized Violence (Individual Level and Social Level)

- Slide 8: Sexualized Violence Pyramid

- Slide 9: Power and Sexualized Violence

- Slide 10: Impacts of Sexualized Violence

- Slide 11: Discussion: Impacts

- Slide 12: Sexualized Violence and Graduate Students

- Slide 13: Consent and Coercion

- Slide 14: Discussion: Power Hierarchies

Slide 6

Facilitator Notes

- Begin by reading the definition of sexualized violence from your post-secondary institution’s sexualized violence policy.

- Point out that many terms can be used to describe violence that is sexual in nature, such as sexual assault or sexual harassment. Tell participants:

- In this workshop, we use the (umbrella) term sexualized violence as it includes all forms of violence that are sexual in nature: physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, and financial.

- As with all forms of violence, sexualized violence can range in severity, and different people will experience the impacts of sexualized violence in different ways.

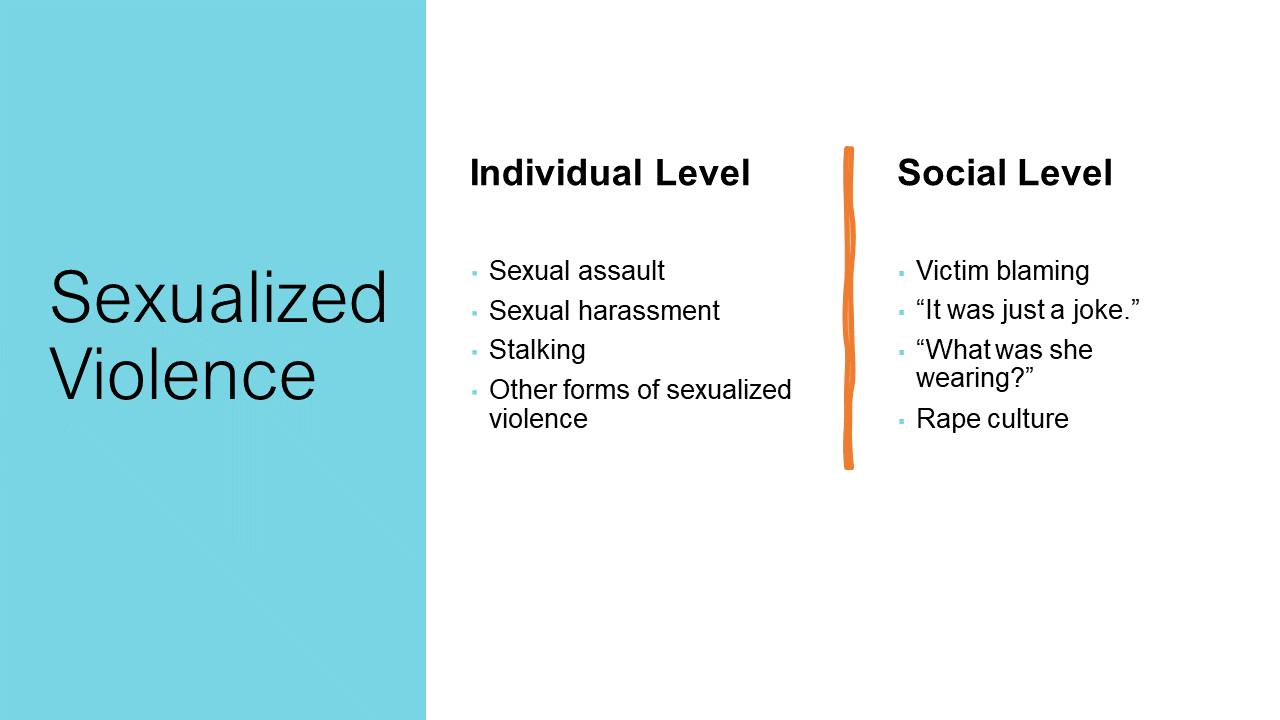

Slide 7

Facilitator Notes

- Sexualized violence on the individual level constitutes a wide range of sexualized acts and behaviours that are unwanted, coerced, committed without consent, or forced either by physical or psychological means. It includes:

- Sexual assault, which is any form of sexual contact without consent

- Sexual harassment, which is any form of unwanted sexual attention or communication

- Stalking behaviours, which involve repeated unwanted contact or communication

- Any form of online sexualized violence, such as sharing intimate photos or videos without consent

- Sexualized violence on the social level encompasses the many attitudes, actions, and social norms that perpetuate and sustain environments where sexual assault and abuse are tolerated, accepted, and denied. This is also called rape culture.

- There is a recognition that the term rape culture may not be the most useful or inclusive term; however, it is currently the most commonly used one to describe the suite of beliefs, values, and actions that allow sexualized violence to be so prevalent.

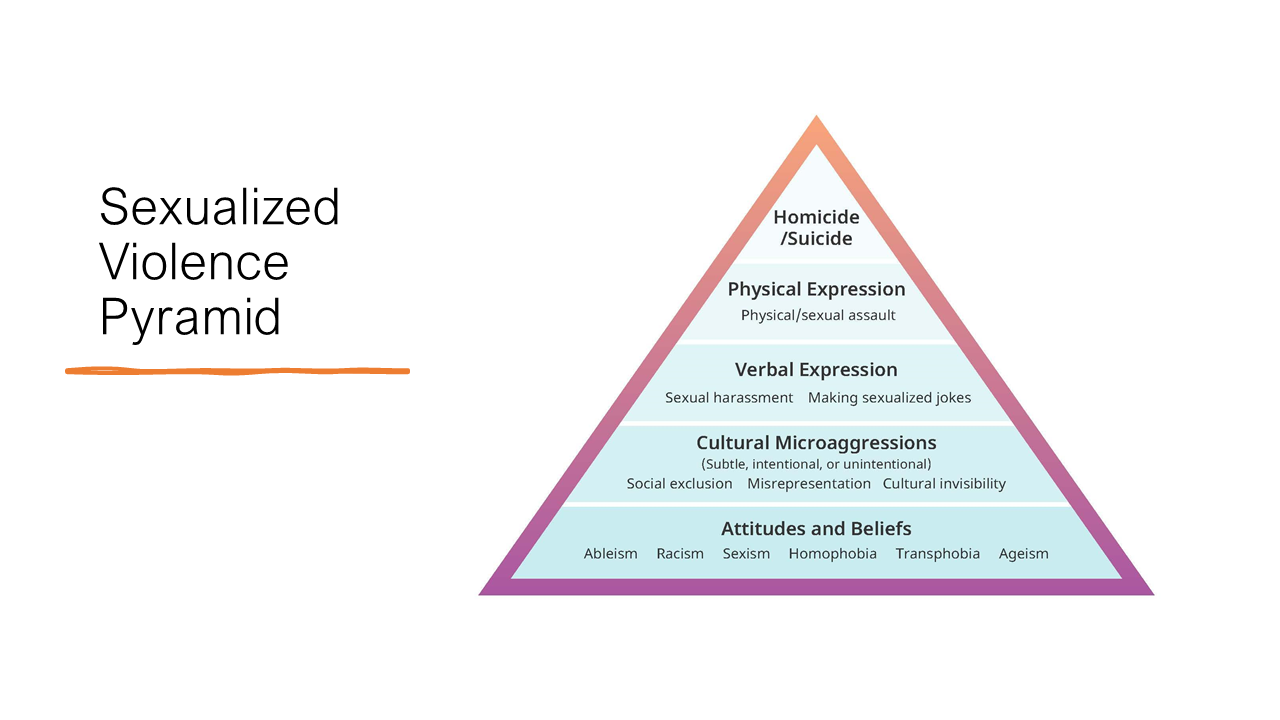

Slide 8

Facilitator Notes

- The bottom of the pyramid shows common attitudes and behaviours, and the top of the pyramid shows some of the more highly recognized forms of sexualized violence. We may refer to some of these behaviours toward the bottom as boundary violations because they are not as easily recognized as acts of sexualized violence as those that are listed at the top of the pyramid. The behaviours on the bottom may not be as overt but can still cause harm and have an impact on those who are subjected to them (e.g., cause feelings of discomfort and violation).

- When the attitudes and behaviours at the bottom of the pyramid are normalized, this helps support the behaviours higher on the pyramid.

- There is a reason why the pyramid is broad at the bottom and narrows at the top, and that’s because everyday actions, words, and beliefs lay the foundation for physical acts of sexualized violence. These attitudes and beliefs at the bottom are what are commonly referred to as rape culture. Victim blaming and protecting perpetrators (both aspects of rape culture) occur throughout the actions at all levels of the pyramid.

- Many people participate, consciously or unconsciously, in actions at the bottom of the pyramid, but not all people escalate their behaviour into the realm of sexual assault.

- Physical expressions of violence can’t happen without the attitudes and beliefs that precede them – they are all connected.

- This pyramid does not suggest that the things at the bottom of the pyramid aren’t serious; these everyday experiences of sexualized violence can have a cumulative impact.

- It is important to differentiate between intent and impact. For example, while the intent of telling a misogynistic joke might be to get a laugh, it has the impact of normalizing that it is okay to devalue, disrespect, and degrade women and femininity, and in turn, creates a culture in which sexualized violence is seen as acceptable or justifiable.

- Sexualized violence is fundamentally about the impact that it has on survivors; not intending to cause harm is not an excuse.

- Optional: Ask participants if they can come up with examples of sexualized violence and where the behaviour would appear in the pyramid. Identify less recognized acts if the participants do not bring them up, such as shaming, bragging, body objectification, non-consensual disclosure of intimate images, leers, exposure, drugging, and stealthing (secret condom removal).

Slide 9

Facilitator Notes

- A common myth about sexualized violence is that it is motivated by sexual desire or attraction. The reality is that this is rarely the case. Rather, sexualized violence is an expression of power and often results from and reproduces power imbalances and inequities. We can think about this on both the individual and the social level too:

- On the individual level, forcing unwanted contact or attention on another person always involves a dynamic of power and control.

- People in positions of authority might abuse that authority to coerce someone they have power over.

- People also commit sexualized violence because they feel a sense of entitlement, such as the belief that someone else owes them sex or that they have the right to someone else’s body or sexuality.

- In all these situations, the perpetrator disregards the needs, wants, and well-being of the other person to get what they want, while the survivor’s power and choice are taken away. This dynamic of power and dominance is at the root of all forms of sexualized violence.

- Sexualized violence can happen to anyone, but it does not impact all communities equally. Sexualized violence is disproportionately experienced by women and groups of people who experience different forms of social, economic, and political marginalization or oppression. Marginalized survivors often experience unique barriers to accessing support.

- Colonization and sexualized violence are interconnected, which has led to a reality in which Indigenous women, girls, and others who don’t align with colonial understandings of gender and sexuality are disproportionately impacted by sexualized violence.

- In a few slides we will discuss where power imbalances can be present for graduate students.

Slide 10

Facilitator Notes

- Sexualized violence is a traumatic event. There is a growing awareness about the impacts of trauma in various areas of a survivor’s life:

- Psychological and emotional impacts include anxiety, terror, shock, shame, emotional numbness, disconnection, intrusive thoughts, helplessness and powerlessness, nightmares, depression, irritability and jumpiness, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harm, suicidality, and substance abuse.

- Physical impacts include injuries, fatigue/exhaustion, disrupted sleep, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), intestinal problems, sexual dysfunction, high-risk sexual behaviour, and unplanned pregnancy.

- The potential professional and financial impacts of sexualized violence on graduate students are numerous, especially if a student has multiple roles within their post-secondary institution. Survivors may risk being ostracized from their field of study, require a leave of absence, need a change in supervisors or institution, or abandon their degree altogether. Financially, any of these impacts could be incredibly costly to a graduate student.

Slide 11

Facilitator Notes

- For the large group discussion, invite participants to read the question on the slide and share their thoughts with the large group. If facilitating online, ask participants to unmute and talk or put their comments in the chat.

- Participants may share the some of these professional impacts:

- Decreased work or academic performance because of stress (e.g., lack of sleep, inability to focus on studies, avoiding work duties)

- Deciding to drop out or leave one’s program because of the harm they’ve been subjected to

- Compounding existing marginalization or feelings of isolation within one’s program or institution

- Arguably the stakes for experiencing sexualized violence and deciding what to do following an experience are highest for graduate students when the decision to take a leave of absence, change supervisors or institutions, or abandon their degree are incredibly costly, especially for students who are deeply linked to a specific institution, department, or field of study (Pescitelli, 2018).

- You could share Handout 1: Supporting Survivors of Sexualized Violence after this discussion (See Appendix 1: Handouts).

Important points to share with participants:

- These described impacts of sexualized violence are reactions we may see in ourselves or others who have experienced sexualized violence.

- However, there is no “correct way” to respond to trauma.

- People may be hesitant or unwilling to disclose sexualized violence.

- How we respond to a disclosure is very important and can impact a survivor’s emotional and psychological health.

Slide 12

Facilitator Notes

- Over the last several years, there has been increased attention and research on sexualized violence in post-secondary contexts.

- The statistics on this slide show the prevalence of sexualized violence for post-secondary students. (Burcyzcka, 2020; Ontario Women’s Directorate, 2013).

- The third statistic helps highlight the role that power often plays in boundary violations at post-secondary institutions (Peter & Stewart, 2019).

- It’s important to note that sexualized violence can happen to anyone. However, women are significantly more likely than men to experience sexualized violence and certain groups are more at risk of being targeted due to their intersecting social positions.

- Marginalized groups, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit women, women with disabilities, and 2SLGBTQIA+ people, experience sexualized violence at higher rates.

- Indigenous women are almost three times as likely to experience violence (physical and/or sexual) than non-indigenous women (Brennan, 2011).

Slide 13

Facilitator Notes

- To help understand sexualized violence and its prevalence in the academic environment, it’s important to acknowledge both consent and coercion.

- Conversations about consent often focus on the legal definition. Consent is defined in Canada’s Criminal Code as the voluntary agreement to engage in a sexual activity. Consent must be affirmatively communicated through words or actions, and it must be ongoing and continuously discussed. Silence or passivity is not consent. It is also not consent if a person is impaired by drugs or alcohol.

- The problem with the legal definition of consent is that it doesn’t address context and assumes all relationships are neutral. A graduate student might say yes to meeting a friend for a drink. However, the dynamics are very different if that graduate student is invited to go for a drink with an instructor or advisor. When someone in a position of authority asks to meet a student for a drink, the student may feel like they can’t say no because they might experience negative consequences. These power hierarchies can consciously or even unconsciously impact our decision-making.

- Coercion can involve the use of threats or physical force but can also include using social norms and power relations to pressure someone to engage in sexual activity. For example, there may be after-hours events in your program that you are unable to attend, but declining an invitation could impact your career trajectory. The coercion does not have to be explicit to be coercion. Technically, you are consenting to go, but you are making that decision based on avoiding these negative consequences.

- Graduate students can have a lot at stake when deciding how to engage (or not engage) with those in direct positions of power over their academic and professional success. In the next slide, we will discuss examples of power dynamics and their relationship to sexualized violence in graduate school.

Slide 14

Facilitator Notes

- Certain institutional cultures and settings have environmental factors and power dynamics that set the stage for coercive behaviour.

- Tell participants that you’re going discuss how graduate studies and academic institutions, in general, can contribute to a culture where boundaries are not always respected.

- Invite participants to read the questions on the slide and share their responses with the group. If facilitating online, ask participants to unmute and talk or put their comments in the chat.

- Note: If you have time, this activity works well as a small-group discussion (or as a breakout room discussion if online). Have participants work in small groups of no more than four. Give the small groups 10 minutes to brainstorm responses to the questions on the slide and then have the groups share with the large group.

- The details that emerge from this discussion may be specific to participants’ fields of study or programs. For example, students in engineering programs may note gender imbalances and a prevalence of sexualized language. Social work students may mention that they spend time doing research in isolated community environments. Encourage participants to reflect on experiences they have witnessed or heard about.

Participants may note the following:

- Power hierarchies (relationships): Participants may provide examples of the various roles graduate students can occupy, such as student, teaching assistant, research assistant, faculty, and member or leader of student groups. Discussion should focus on the various power hierarchies these relationships can produce (e.g., supervisors having power and authority over graduate students, or graduate students having power and authority over others). Discuss how this power can contribute to coercion directly or implied.

- Norms: Participants may note that graduate students are a diverse group of individuals. They may be working professionals or have children and other family responsibilities. They may have a close relationship with their supervisor, where socializing and drinking are normalized. They may be more isolated from campus life and often required to work off campus or in isolated spaces, or they could be supervised by community members in practicums and internship placements.

- Attitudes: Participants may talk about an unrealistic workload and culture of competition with little regard for work-life balance support. There is often a culture where sexualized violence is more likely to occur, and seasoned, tenured faculty have a sense of entitlement and credibility. A high value is placed on loyalty to the supervisor and institution (Students for Consent Culture Canada, 2021). The stakes for graduate students are arguably the highest if they decide to take a leave of absence, change supervisors or institutions, or abandon their degree. All are incredibly costly, especially for students who are deeply linked to a specific institution, department, or field of study (Pescitelli, 2018).

- Behaviours: Participants may discuss sexualized jokes, innuendo, objectification, and other foundational-level actions on the pyramid of sexualized violence.