Chapter 5. Immigration and the Immigrant Experience

5.9 Immigrants and War

Perhaps the single greatest irony of Canadians’ relationship with immigrants and visible minorities (including Aboriginal people) rose to the surface in the course of two World Wars. Keen to welcome nation-building immigrants but critical of their cultures and suspicious of the kind of nation they might build, Canadians tied themselves in knots when it came time to engage in military adventures.

The diversity introduced to Canada from the 19th century complicated ideas of loyalty. Recall that Anglo-Canadians were extremely suspicious of Franco-Catholic loyalties to the Vatican as articulated by the ultramontanists. The loyalty of the French at the secular level was regularly drawn into question — so often so that the apparent disinterest of Québecois in volunteering for service in 1914-17 (see Section 6.4) was both expected and viewed as demonstrable proof of disloyalty to the Crown — regardless of the fact that Anglo-Canadian numbers in the ranks were shored up mightily by recent British immigrants. French Canadians, for their part, characterized Anglo-Canadians as absurdly loyal to an absent monarch in a foreign country, rather than to the country of their birth: Canada. What, then, were they to make of the hundreds of thousands of Europeans and Asians drawn from beyond the borders of France and Britain?

Local xenophobia was, thus, amplified by the arrival of war in 1914. Germans were instantly persecuted, their property attacked, and calls raised for sweeping arrests. Germanic names were part of the landscape of British North America for centuries and now they were Anglicized to demonstrate loyalty and to reduce visibility. Even the Ontario city of Berlin took the name of the British general in the Boer War, Kitchener. Austro-Hungarians — that is, Austrians, Hungarians, many Ukrainians, and almost everyone from the Balkans — were also targeted. The Hapsburg Empire’s vilification in wartime propaganda gave license to indulge prejudice and hostility toward those Central and Southern European immigrants who had been recruited — at no small expense — to build the Canadian West’s economy. What’s more, eugenicists already regarded the Austro-Hungarians as a liability in the building of a forthright, strong, British nation; Austro-Hungarians were perceived by government and civic officials as inherently impoverished and therefore feckless and unhealthy as well. And now, in wartime, they were subject to arrest and incarceration in internment camps.

Anglo- and Franco-Canadians, however, proved flexible in their distaste for foreigners. At the end of WWI, when the map of Europe was redrawn at Versailles, much of the Ukraine now fell within the borders of Poland, a beleaguered nation-state towards which the public had some sympathies. To be an Austro-Hungarian was to be an enemy; to be a Pole was to be reinvented as a brave ally.

The Pacificists

Pacificism was another barrier to inclusion during wartime. Several immigrant communities were recruited under Sifton’s watch with the promise that their pacifist beliefs would be honoured in Canada. For the Mennonites in particular, this was a critical assurance. In Russia, they were the target of violent repression by the Czarist regime precisely because of their anti-war stance; Canada’s offer to respect their pacificism was a deal-maker.

The Doukhobor experience in this regard offers an example. A dissenting sect established in Russia and Georgia during the 17th century (if not earlier), the Doukhobors’ critique of established church authority and the secular state in Russia attracted repression. This peaked in 1895 when the regime of Nicholas II sent in storm troops — in this case, Cossacks — to force Doukhobor compliance with state laws and universal conscription. These events produced an international outcry and the search for a new home for the Doukhobors (something which the frustrated Czar was only too happy to permit). Sifton’s ministry stepped forward and offered block settlements in Saskatchewan and Alberta totalling more than three-quarters of a million acres. The communal-ownership model preferred by the Doukhobors was to be respected, as was their anarchist reluctance to engage with the bureaucratic machinery of the state. As well, the Doukhobors were reassured by revisions to the Dominion Military Act that exempted them from military service.

Three factors caused the Canadians to change their position on the Doukhobor agreements. The bureaucracy of the modern state became more rigorous: Sifton’s replacement, Frank Oliver, began insisting on individual land registrations and pressures grew to send Doukhobor children to public schools. As tensions grew in Europe, an oath of allegiance to the Crown was required. Provincial governments were established in Alberta and Saskatchewan; now the Doukhobors had several levels of government with which to deal.

The communities fractured and the largest part, calling itself the Sons of Freedom, migrated to the southeast of British Columbia. There, their anti-materialist protests (which involved nude demonstrations and the burning of buildings) and their opposition to public schooling peaked in the 1920s and then in the mid-20th century. The growing state formation under W. A. C. Bennett moved to capture Doukhobor children and to educate them in facilities secure from parental influence. Arrests of the Freedomites followed. While all of these steps were taken within the letter of the law, the Doukhobor community experienced their incarceration and the abduction of their children as nothing short of state terrorism. Within only a few decades, the Doukhobor experience in Canada looked very much like what it had been under the Czars.

What this history demonstrates is, in part, the conflicting currents of modernism – which involves the growth of the state, record-keeping, militarism, and the primacy of the individual — and the survival of pre- or antimodernist belief systems and inclinations — including the idealization of rural and communal life, spiritual versus materialist priorities, and anarchistic resistance to the very idea of the nation-state.

Key Points

- Canadian policy, and much of the public, turned against Central and Eastern European immigrants during wartime.

- Certain groups were characterized as “enemy aliens” and faced internment during the Great War.

- Pacifist colonies in the West and elsewhere in Canada were increasingly confronted by public opinion and governments that reneged on earlier assurances of tolerance.

Media Attributions

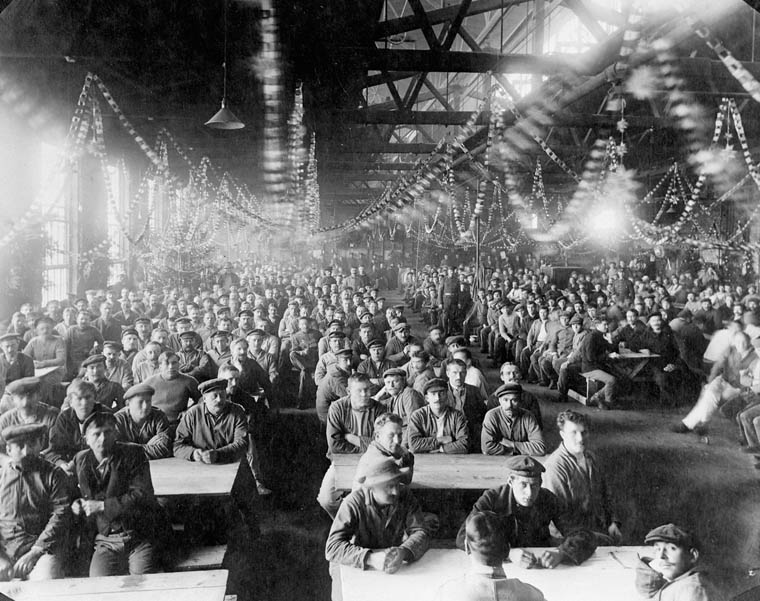

- Christmas celebration at Internment Camp in Canada, WWI, 1916 © Internment Camps, Library and Archives Canada (C-014104) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Village of Vosnesenya, Thunder Hill Colony © Library and Archives Canada (C-000683) is licensed under a Public Domain license

An anti-war position; pacifists typically will not volunteer for and refuse to be conscripted into conflict. Many eastern European religious groups brought pacifist beliefs with them to Western Canada before 1914.

An individual who advocates the dismantling of the state and the creation of a structure based on voluntary association and participation.

Or Freedomites; a radical anarchist faction within the Doukhobor diaspora in Canada; broke away from the main settlements in Saskatchewan and resettled in southeastern British Columbia; anti-materialist protests and anti-statism led to confrontations with the provincial government in the 1920s, and 1950s–1960s.

A retreat from modernization and modernity, often associated with rural and traditional values, spirituality, and social hierarchies.