Chapter 16. Gender, Sexuality and Anti-Oppression

GS.24: Deep Dive – Sexology: Sex Research

Approximate reading time: 8 minutes

Exploring Human Sexuality: Insights from Sex Research

The study of human sexuality, known as sexology, is a fascinating and complex field that intersects various disciplines including psychology, biology, and sociology. It aims to understand the many aspects of sexual behaviour, preferences and functioning. Sexologists — the experts in this field — employ their extensive training to explore and explain the diverse facets of human sexuality.

Their work spans several domains, from clinical practice and counselling to educational roles and groundbreaking research. These professionals delve into the intricacies of sexual behaviour and emotions, offering guidance and solutions to individuals grappling with sexual issues, and improving their overall quality of life (Tilley, 2015).

Pioneering Research by Kinsey

Before the late 1940s, access to reliable, empirically-based information on sex was limited. Physicians were considered authorities on all issues related to sex, despite the fact that they had little to no training in these issues, and it is likely that most of what people knew about sex had been learned either through their own experiences or by talking with their peers. Convinced that people would benefit from a more open dialogue on issues related to human sexuality, Dr. Alfred Kinsey of Indiana University initiated large-scale survey research on the topic. The results of some of these efforts were published in two books: Sexual behaviour in the Human Male, and Sexual behaviour in the Human Female, which were published in 1948 and 1953, respectively (Bullough, 1998).

In 1947, Alfred Kinsey established The Kinsey Institute for Research, Sex, Gender and Reproduction at Indiana University, shown here in 2011. The Kinsey Institute has continued as a research site of important psychological studies for decades.

At the time, the Kinsey reports were quite sensational. Never before had the American public seen its private sexual behaviour become the focus of scientific discussion on such a large scale. The books, which were filled with statistics and scientific lingo, sold remarkably well to the general public, and people began to engage in open conversations about human sexuality. As you might imagine, not everyone was happy that this information was being published. In fact, these books were banned in some countries. Ultimately, the controversy resulted in Kinsey losing funding that he had secured from the Rockefeller Foundation to continue his research efforts (Bancroft, 2004).

Although Kinsey’s research has been widely criticised as being riddled with sampling and statistical errors (Jenkins, 2010), there is little doubt that this research was very influential in shaping future research on human sexual behaviour and motivation. Kinsey described a remarkably diverse range of sexual behaviours and experiences reported by the volunteers participating in his research. Behaviours that had once been considered exceedingly rare or problematic were shown to be much more common and harmless than previously thought. (Bancroft, 2004; Bullough, 1998).

Among the results of Kinsey’s research were the findings that women are as interested and experienced in sex as men, that both females and males masturbate without adverse health consequences, and that homosexual acts are fairly common (Bancroft, 2004). Kinsey also developed a continuum known as the Kinsey scale (See the Kinsey Scale in the previous discussion, in Learning about Binary, Continuum, and Sliding Scale Models above) that is still commonly used today to categorise an individual’s sexual orientation (Jenkins, 2010). Sexual orientation is an individual’s emotional and erotic attractions to same-sexed (now called same gender) individuals (homosexual), individuals from opposite-sex (now called other gender) (heterosexual), or both (bisexual).

In this textbook, we will refer to women and men when referring to historical data that was originally categorised by researchers as a binary gender.

When discussing gender in the present or future tense we will update gender-based language to avoid reinforcing misleading binary gender oversimplifications.

Advancements by Masters and Johnson

William Masters (1915-2001) and Virginia Johnson (1925-2013) formed a research team in 1957 that expanded studies of sexuality from merely asking people about their sex lives to measuring people’s anatomy and physiology while they were actually having sex. Masters was a former Navy lieutenant, and trained gynaecologist with an interest in studying sex workers. Johnson was a former country music singer with an interest in studying sociology. Masters and Johnson became romantic partners, and eventually married each other but later divorced. Despite their colourful private lives they were dedicated researchers with an interest in understanding sex from a scientific perspective.

In 1966, William Masters and Virginia Johnson published a book detailing the results of their observations of nearly 700 people who agreed to participate in their study of physiological responses during sexual behaviour. Unlike Kinsey, who used personal interviews and surveys to

collect data, Masters and Johnson observed people having intercourse in a variety of positions, and they observed people masturbating, manually or with the aid of a device. While this was occurring, researchers recorded measurements of physiological variables, such as blood pressure and respiration rate, as well as measurements of sexual arousal, such as vaginal lubrication and penile tumescence (swelling associated with an erection). In total, Masters and Johnson observed nearly 10,000 sexual acts as a part of their research (Hock, 2008).

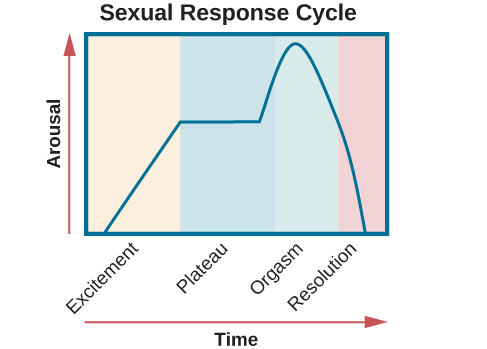

Based on these observations, Masters and Johnson divided the sexual response cycle into four phases that are fairly similar in a person with a clitoris and vagina as compared to a person with a penis: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

The Sexual Response Cycle

- Excitement: Activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system defines the excitement phase; heart rate and breathing accelerate, along with increased blood flow to the vaginal walls, clitoris, penis, and nipples (vasocongestion). Involuntary muscular movements (myotonia), such as facial grimaces, also occur during this phase.

- Plateau: Blood flow, heart rate, and breathing intensify during the plateau phase. During this phase, often referred to as “foreplay”, females experience an orgasmic platform (the outer third of the vaginal walls tightening) and males experience a release of pre-seminal fluid containing healthy sperm cells (Killick et al., 2011). This early release of fluid makes penile withdrawal a relatively ineffective form of birth control (Aisch & Marsh, 2014).

- Orgasm: The shortest but most pleasurable phase is the orgasm phase. After reaching its climax, neuromuscular tension is released and the hormone oxytocin floods the bloodstream, facilitating emotional bonding. Although the rhythmic muscular contractions of an orgasm are temporally associated with ejaculation, this association is not necessary because orgasm and ejaculation are two separate physiological processes.

- Resolution: The body returns to a pre-aroused state in the resolution phase. Most males enter a refractory period of being unresponsive to sexual stimuli. The length of this period depends on age, frequency of recent sexual relations, level of intimacy with a partner, and novelty. Because most females do not have a refractory period, they have a greater potential, physiologically, of having multiple orgasms.

This foundational research by Masters and Johnson, along with Kinsey’s earlier work, has significantly influenced our understanding of human sexuality, making it a subject of serious academic inquiry and public discussion.

Image Attributions

Figure SUP GS.1. Figure 10.17 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).