Chapter 17. Well-Being

WB.2: Deep Dive – The Science of Happiness: Research Findings

Approximate reading time: 5 minutes

What really makes us happy? Researchers have been exploring this for years, trying to understand if things like money, looks, possessions, enjoyable jobs, or good relationships make a difference. Here’s what they found:

Age and Happiness

As people get older, they tend to feel more satisfied with life. However, happiness doesn’t seem to differ much between men and women (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999).

Family and Relationships

Close relationships, like being married, seem to make people happier. Those who are happily married report being happier than those who are single, divorced, or widowed (Diener et al., 1999). Good marriages and strong social connections are linked to happiness (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

Money and Happiness

This is a tricky one. Yes, money can buy happiness to an extent. People in richer countries and those who are wealthier tend to be happier. But, happiness only increases with income up to a certain point. After about $75,000 per year, more money doesn’t necessarily mean more happiness (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Surprisingly, having more money can sometimes stop people from enjoying simple things in life (Kahneman, 2011; Quoidbach et al., 2010).

Education, Employment, and Happiness

Happy people are more likely to have graduated from college and to have jobs that they find meaningful. Education has a slight connection to happiness, but being smart doesn’t directly make you happier (Diener et al., 1999).

Religion and Happiness

Generally, religious people report being happier. This connection depends a lot on where you live. In places with tougher living conditions, being religious is linked to greater well-being (Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011).

Culture and Happiness

If your personality and values fit well with your culture, you’re likely to be happier. For example, in cultures that value individualism, self-esteem is a big factor in happiness (Diener, Diener, & Diener, 1995; Diener, 2012).

So, while many factors contribute to happiness, things like parenthood and physical attractiveness don’t seem to have a strong link. Although people often think having children is key to a happy life, research suggests that those without children are usually happier (Hansen, 2012). And how attractive you think you are matters more for happiness than your actual looks (Diener, Wolsic, & Fujita, 1995).

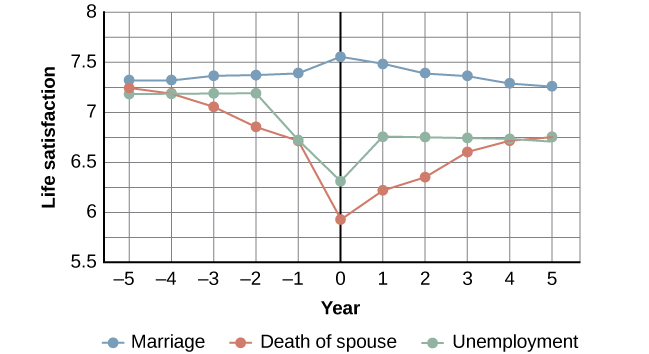

Recently, researchers have been looking at whether big life events permanently change our happiness levels (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006). It seems that sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t. For example, marriage might not keep making us happier, but unemployment or severe disabilities might lead to a long-term drop in happiness. A study showed that after events like marriage, unemployment, or losing a spouse, people’s happiness levels changed; sometimes they went back to normal, sometimes they didn’t (Diener et al., 2006; Fujita & Diener, 2005).

This graph (Figure SUP WB.2) shows how people’s happiness changed before and after big life events like getting married, losing a job, or losing a spouse. For marriage, happiness peaked around the wedding then slightly dropped. For unemployment and losing a spouse, happiness fell sharply and then recovered a bit, but not completely.

Image Attributions

Figure SUP WB.1. Figure 14.27 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License and contains modifications of the following works:

- credit a: modification of work by Phil Roeder;

- credit b: modification of work by Robert S. Donovan

Figure SUP WB.2. Figure 14.28 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).