Main Body

Chapter 12. Peer Review and Final Revisions

12.1 Revision

Learning Objectives

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising

- Use peer reviews and checklists to assist revising

- Revise your paper to improve organization and cohesion

- Determine an appropriate style and tone for your paper

- Revise to ensure that your tone is consistent

- Revise the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means that little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practise, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

You should revise and edit in stages: do not expect to catch everything in one go. If each time you review your essay you focus on a different aspect of construction, you will be more likely to catch any mistakes or identify any issues. Throughout this chapter, you will see a number of checklists containing specific things to look for with each revision. For example, you will first look at how the overall paper and your ideas are organized.

In the second section of this chapter, you will focus more on editing: correcting the mechanical issues. Also at the end of the chapter, you will see a comprehensive but more general list of things you should be looking for.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

When you revise, you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

When you edit, you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

Tip

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them throughout the writing process; then keep using the ones that bring results.

Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

For many people, the words critic, critical, and criticism provoke only negative feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. To do this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Revising Your Paper: Organization, Cohesion, and Unity

When writing a research paper, it is easy to become overly focused on editorial details, such as the proper format for bibliographical entries. These details do matter. However, before you begin to address them, it is important to spend time reviewing and revising the content of the paper.

A good research paper is both organized and cohesive. Organization means that your argument flows logically from one point to the next. Cohesion means that the elements of your paper work together smoothly and naturally. In a cohesive research paper, information from research is seamlessly integrated with the writer’s ideas.

Revise to Improve Organization

When you revise to improve organization, you look at the flow of ideas throughout the essay as a whole and within individual paragraphs. You check to see that your essay moves logically from the introduction to the body paragraphs to the conclusion, and that each section reinforces your thesis. Use Checklist 12.1: Revise for Organization to help you.

Checklist 12.1: Revise for Organization

At the essay level

Does my introduction proceed clearly from the opening to the thesis?

Does each body paragraph have a clear main idea that relates to the thesis?

Do the main ideas in the body paragraphs flow in a logical order? Is each paragraph connected to the one before it?

Do I need to add or revise topic sentences or transitions to make the overall flow of ideas clearer?

Does my conclusion summarize my main ideas and revisit my thesis?

At the paragraph level

Does the topic sentence clearly state the main idea?

Do the details in the paragraph relate to the main idea?

Do I need to recast any sentences or add transitions to improve the flow of sentences?

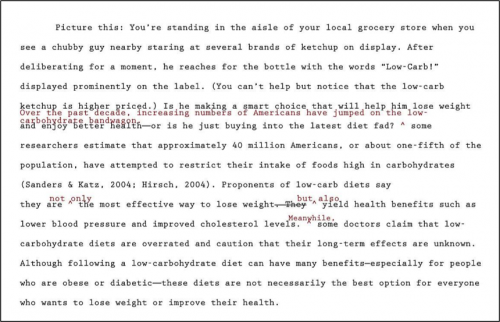

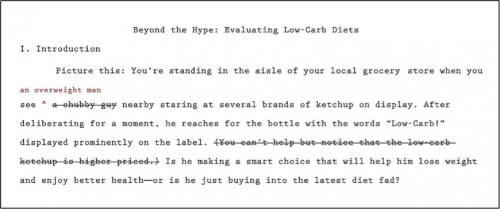

Jorge reread his draft paragraph by paragraph. As he read, he highlighted the main idea of each paragraph so he could see whether his ideas proceeded in a logical order. For the most part, the flow of ideas was clear. However, he did notice that one paragraph did not have a clear main idea. It interrupted the flow of the writing. During revision, Jorge added a topic sentence that clearly connected the paragraph to the one that had preceded it. He also added transitions to improve the flow of ideas from sentence to sentence.

Read the following paragraphs twice, the first time without Jorge’s changes, and the second time with them.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.1

Follow these steps to begin revising your paper’s overall organization.

Print out a hard copy of your paper. (You will use this for multiple self-practice exercises in this chapter.)

Read your paper paragraph by paragraph. Highlight your thesis and the topic sentence of each paragraph.

Using the thesis and topic sentences as starting points, outline the ideas you presented—just as you would do if you were outlining a chapter in a textbook. Do not look at the outline you created during prewriting. You may write in the margins of your draft or create a formal outline on a separate sheet of paper.

Next, reread your paper more slowly, looking for how ideas flow from sentence to sentence. Identify places where adding a transition or recasting a sentence would make the ideas flow more logically.

Review the topics on your outline. Is there a logical flow of ideas? Identify any places where you may need to reorganize ideas.

Begin to revise your paper to improve organization. Start with any major issues, such as needing to move an entire paragraph. Then proceed to minor revisions, such as adding a transitional phrase or tweaking a topic sentence so it connects ideas more clearly.

Optional collaboration: Please share your paper with a classmate. Repeat the six steps and take notes on a separate piece of paper. Share and compare notes.

Tip

Writers choose transitions carefully to show the relationships between ideas—for instance, to make a comparison or elaborate on a point with examples. Make sure your transitions suit your purpose and avoid overusing the same ones.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Earlier chapters have discussed using transitions for specific purposes in the planning of your writing. Table 12.1: Common Transitional Words and Phrases groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 12.1: Common Transitional Words and Phrases According to Purpose

| Transitions That Show Sequence or Time | ||

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | first, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| Transitions That Show Position | ||

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| Transitions That Show a Conclusion | ||

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |

| in the final analysis | therefore | thus |

| Transitions That Continue a Line of Thought | ||

| consequently | furthermore | additionally |

| because | besides the fact | following this idea further |

| in addition | in the same way | moreover |

| looking further | considering…, it is clear that | |

| Transitions That Change a Line of Thought | ||

| but | yet | however |

| nevertheless | on the contrary | on the other hand |

| Transitions That Show Importance | ||

| above all | best | especially |

| in fact | more important | >most important |

| most | worst | |

| Transitions That Introduce the Final Thoughts in a Paragraph or Essay | ||

| finally | last | in conclusion |

| most of all | least of all | last of all |

| All Purpose Transitions to Open Paragraphs or to Connect Ideas Inside Paragraphs | ||

| admittedly | at this point | certainly |

| granted | it is true | generally speaking |

| in general | in this situation | no doubt |

| no one denies | obviously | of course |

| to be sure | undoubtedly | unquestionably |

| Transitions that Introduce Examples | ||

| for instance | for example | such as |

| Transitions That Clarify the Order of Events or Steps | ||

| first, second, third | generally, furthermore, finally | in the first place, also, last |

| in the first place, furthermore, finally | in the first place, likewise, lastly | |

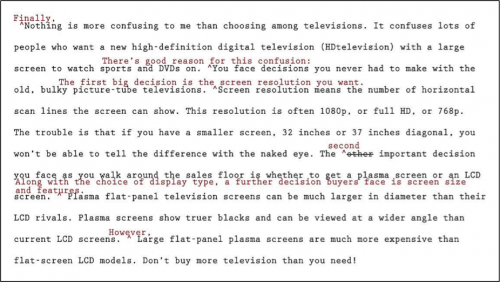

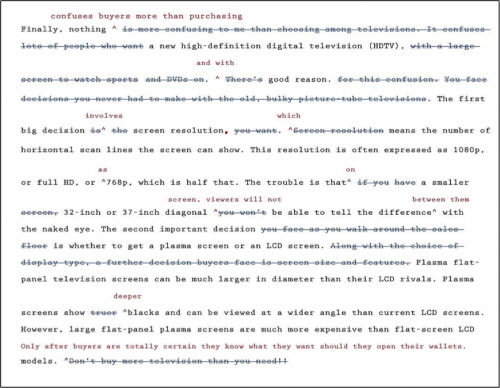

When Mariah (who you were introduced to in Chapters 5 and 6) revised her essay for unity, she examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Tip

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.2

Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

Do you agree with the transitions and other changes that Mariah made to her paragraph? Which would you keep and which were unnecessary? Explain.

What transition words or phrases did Mariah add to her paragraph? Why did she choose each one?

What effect does adding additional sentences have on the coherence of the paragraph? Explain. When you read both versions aloud, which version has a more logical flow of ideas? Explain.

Revise to Improve Cohesion

When you revise to improve cohesion, you analyze how the parts of your paper work together. You look for anything that seems awkward or out of place. Revision may involve deleting unnecessary material or rewriting parts of the paper so that the out of place material fits in smoothly.

In a research paper, problems with cohesion usually occur when a writer has trouble integrating source material. If facts or quotations have been awkwardly dropped into a paragraph, they distract or confuse the reader instead of working to support the writer’s point. Overusing paraphrased and quoted material has the same effect. Use Checklist 12.2: Revise for Cohesion to review your essay for cohesion.

Checklist 12.2: Revise for Cohesion

Does the opening of the paper clearly connect to the broader topic and thesis? Make sure entertaining quotes or anecdotes serve a purpose.

Have I included support from research for each main point in the body of my paper?

Have I included introductory material before any quotations? Quotations should never stand alone in a paragraph.

Does paraphrased and quoted material clearly serve to develop my own points?

Do I need to add to or revise parts of the paper to help the reader understand how certain information from a source is relevant?

Are there any places where I have overused material from sources?

Does my conclusion make sense based on the rest of the paper? Make sure any new questions or suggestions in the conclusion are clearly linked to earlier material.

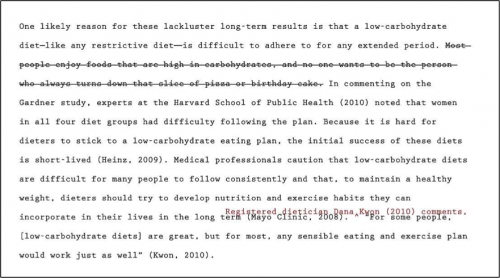

As Jorge reread his draft, he looked to see how the different pieces fit together to prove his thesis. He realized that some of his supporting information needed to be integrated more carefully and decided to omit some details entirely. Read the following paragraph, first without Jorge’s revisions and then with them.

Jorge decided that his comment about pizza and birthday cake came across as subjective and was not necessary to make his point, so he deleted it. He also realized that the quotation at the end of the paragraph was awkward and ineffective. How would his readers know who Kwon was or why her opinion should be taken seriously? Adding an introductory phrase helped Jorge integrate this quotation smoothly and establish the credibility of his source.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.3

Follow these steps to begin revising your paper to improve cohesion.

Print out a hard copy of your paper, or work with your printout from Self–Practice Exercise 12.1.

Read the body paragraphs of your paper first. Each time you come to a place that cites information from sources, ask yourself what purpose this information serves. Check that it helps support a point and that it is clearly related to the other sentences in the paragraph.

Identify unnecessary information from sources that you can delete.

Identify places where you need to revise your writing so that readers understand the significance of the details cited from sources.

Skim the body paragraphs once more, looking for any paragraphs that seem packed with citations. Review these paragraphs carefully for cohesion.

Review your introduction and conclusion. Make sure the information presented works with ideas in the body of the paper.

Revise the places you identified in your paper to improve cohesion.

Optional collaboration: Please exchange papers with a classmate. Complete step 4. On a separate piece of paper, note any areas that would benefit from clarification. Return and compare notes.

Writing at Work

Understanding cohesion can also benefit you in the workplace, especially when you have to write and deliver a presentation. Speakers sometimes rely on cute graphics or funny quotations to hold their audience’s attention. If you choose to use these elements, make sure they work well with the substantive content of your presentation. For example, if you are asked to give a financial presentation, and the financial report shows that the company lost money, funny illustrations would not be relevant or appropriate for the presentation.

Tip

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may add information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity, all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence, the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

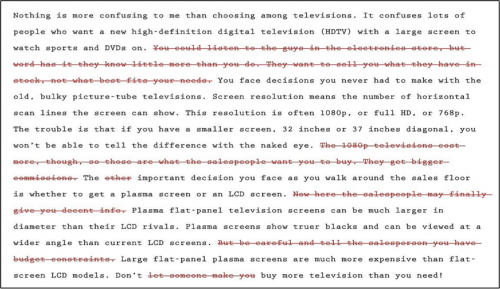

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes and the second time with them.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.4

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Do you agree with Mariah’s decision to make the deletions she made? Did she cut too much, too little, or just enough? Explain.

Is the explanation of what screen resolution means a digression? Or is it audience friendly and essential to understanding the paragraph? Explain.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Now, print out another copy of your essay or use the printed version(s) you used in Self–Practice Exercises 12.1 and 12.3. Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

Tip

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copy editors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copy editors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Using a Consistent Style and Tone

Once you are certain that the content of your paper fulfills your purpose, you can begin revising to improve style and tone. Together, your style and tone create the voice of your paper, or how you come across to readers. Style refers to the way you use language as a writer—the sentence structures you use and the word choices you make. Tone is the attitude toward your subject and audience that you convey through your word choice.

Determining an Appropriate Style and Tone

Although accepted writing styles will vary within different disciplines, the underlying goal is the same—to come across to your readers as a knowledgeable, authoritative guide. Writing about research is like being a tour guide who walks readers through a topic. A stuffy, overly formal tour guide can make readers feel put off or intimidated. Too much informality or humour can make readers wonder whether the tour guide really knows what he or she is talking about. Extreme or emotionally charged language comes across as unbalanced.

To help prevent being overly formal or informal, determine an appropriate style and tone at the beginning of the research process. Consider your topic and audience because these can help dictate style and tone. For example, a paper on new breakthroughs in cancer research should be more formal than a paper on ways to get a good night’s sleep.

A strong research paper comes across as straightforward, appropriately academic, and serious. It is generally best to avoid writing in the first person, as this can make your paper seem overly subjective and opinion based. Use Checklist 12.3: Revise for Style to review your paper for other issues that affect style and tone. You can check for consistency at the end of the writing process. Checking for consistency is discussed later in this section.

Checklist 12.3: Revise for Style

My paper avoids excessive wordiness.

My sentences are varied in length and structure.

I have avoided using first person pronouns such as I and we.

I have used the active voice whenever possible.

I have defined specialized terms that might be unfamiliar to readers.

I have used clear, straightforward language whenever possible and avoided unnecessary jargon.

My paper states my point of view using a balanced tone—neither too indecisive nor too forceful.

Word Choice

Note that word choice is an especially important aspect of style. In addition to checking the points noted on Checklist 12.3, review your paper to make sure your language is precise, conveys no unintended connotations, and is free of bias. Here are some of the points to check for:

Vague or imprecise terms

Slang

Repetition of the same phrases (“Smith states…, Jones states…”) to introduce quoted and paraphrased material (For a full list of strong verbs to use with in text citations, see Chapter 9: Citations and Referencing.)

Exclusive use of masculine pronouns or awkward use of heorshe

Use of language with negative connotations, such as haughty or ridiculous

Use of outdated or offensive terms to refer to specific ethnic, racial, or religious groups

Tip

Using plural nouns and pronouns or recasting a sentence can help you keep your language gender neutral while avoiding awkwardness. Consider the following examples.

- Gender biased: When a writer cites a source in the body of his paper, he must list it on his references page.

- Awkward: When a writer cites a source in the body of his or her paper, he or she must list it on his or her references page.

- Improved: Writers must list any sources cited in the body of a paper on the references page.

Keeping Your Style Consistent

As you revise your paper, make sure your style is consistent throughout. Look for instances where a word, phrase, or sentence does not seem to fit with the rest of the writing. It is best to reread for style after you have completed the other revisions so that you are not distracted by any larger content issues. Revising strategies you can use include the following:

Read your paper aloud. Sometimes your ears catch inconsistencies that your eyes miss.

Share your paper with another reader whom you trust to give you honest feedback. It is often difficult to evaluate one’s own style objectively—especially in the final phase of a challenging writing project. Another reader may be more likely to notice instances of wordiness, confusing language, or other issues that affect style and tone.

Edit your paper slowly, sentence by sentence. You may even wish to use a sheet of paper to cover up everything on the page except the paragraph you are editing. This practice forces you to read slowly and carefully. Mark any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

On reviewing his paper, Jorge found that he had generally used an appropriately academic style and tone. However, he noticed one glaring exception—his first paragraph. He realized there were places where his overly informal writing could come across as unserious or, worse, disparaging. Revising his word choice and omitting a humorous aside helped Jorge maintain a consistent tone. Read his revisions.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.5

Using Checklist 12.3: Revise for Style, revise your paper line by line. You may use either of these techniques:

Print out a hard copy of your paper or work with your printout from Self–Practice Exercise 12.1. Read it line by line. Check for the issues noted on Checklist 12.3, as well as any other aspects of your writing style you have previously identified as areas for improvement. Mark any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

If you prefer to work with an electronic document, use the menu options in your word processing program to enlarge the text to 150 or 200 percent of the original size. Make sure the type is large enough that you can focus on one paragraph at a time. Read the paper line by line as described in step 1. Highlight any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

Optional collaboration: Please exchange papers with a classmate. On a separate piece of paper, note places where the essay does not seem to flow or you have questions about what was written. Return the essay and compare notes.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers need most is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review.

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review: Organization, Unity, and Coherence

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

This essay is about____________________________________________.

Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

Writing at Work

One of the reasons why word processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that work groups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a work group and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.6

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to consider that feedback in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.7

Consider the feedback you received from the peer review and all of the revision exercises throughout this section. Compile a final draft of your revisions that you can use in the next section to complete your final edits.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

12.2 Editing and Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper

Learning Objectives

- Edit your paper to ensure that language, citations, and formatting are correct

Given all the time and effort you have put into your research paper, you will want to make sure that your final draft represents your best work. This requires taking the time to revise and edit your paper carefully.

You may feel like you need a break from your paper before you edit it. That feeling is understandable, so you want to be sure to leave yourself enough time to complete this important stage of the writing process. This section presents a number of opportunities for you to focus on different aspects of the editing process; as with revising a draft, you should approach editing in different stages.

Some of the content in this section may seem repetitive, but again, it provides you with a chance to double-check any revisions you have made at a detailed level.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah and Jorge have, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Tip

Editing takes time. Be sure to budget time into the writing process to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

Readers do not cheer when you use there, their, and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these methods match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

- Sentences that begin with There is or There are

- Wordy. There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

- Revised. The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

- Sentences with unnecessary modifiers

- Wordy. Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favour of the proposed important legislation.

- Revised. Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favour of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of, with a mind to, on the subject of, as to whether or not, more or less, as far as…is concerned, and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

- Wordy. As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy. A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

- Revised. As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy. Researchers are preparing a report about using geysers as an energy source.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be: Sentences with passive voice verbs often create confusion because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active voice verbs in place of forms of to be, which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

- Wordy. It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

- Revised. Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened

- Wordy. The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone. My over-60 uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

- Revised. The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone. My over-60 uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most essays at the post-secondary level should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 2: Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?

Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer, kewl, and rad.

Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t, I am in place of I’m,have not in place of haven’t, and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy, face the music, better late than never, and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion; complement/compliment; council/counsel; concurrent/consecutive; founder/flounder; and historic/historical. When in doubt, check a dictionary.

Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited.

Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing, people, nice, good, bad, interesting, and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.8

Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

Read the unrevised and the revised paragraphs aloud. Explain in your own words how changes in word choice have affected Mariah’s writing.

Do you agree with the changes that Mariah made to her paragraph? Which changes would you keep and which were unnecessary? Explain. What other changes would you have made?

What effect does removing contractions and the pronoun you have on the tone of the paragraph? How would you characterize the tone now? Why?

Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Self–practice EXERCISE 12.9

Return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words.

Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Brief Punctuation Review

Throughout this book, you have been presented with a number of tables containing transitional words. Table 12.2: Punctuating Transitional Words and Phrases shows many of the transition words you have seen organized into different categories to help you know how to punctuate with each one.

Table 12.2: Punctuating Transitional Words and Phrases

| Joining Independent Clauses (coordination) | ||||||

| 2 IND | Coordinating conjunctions: FANBOYS | Conjunctive adverbs and other transitional expressions | ||||

| IND; IND | IND, ____ IND | IND. _____, IND or IND; _____,IND | ||||

| for | accordingly | after all | ||||

| and | after a while | also | ||||

| nor | anyhow | as a result | ||||

| but | at any rate | at the same time | ||||

| or | besides | consequently | ||||

| yet | for example | for instance | ||||

| so | furthermore | hence | ||||

| henceforth | however | |||||

| in addition | indeed | |||||

| in fact | in other words | |||||

| in particular | instead | |||||

| in the first place | likewise | |||||

| meanwhile | moreover | |||||

| nevertheless | nonetheless | |||||

| on the contrary | on the other hand | |||||

| otherwise | still | |||||

| then | therefore | |||||

| thus | ||||||

| Forming Dependent Clauses (subordination) | ||||||

| IND +DEP or DEP,IND | ||||||

| after | although | as | as if | as though | ||

| because | before | if | in order that | since | ||

| so that | that | though | unless | until | ||

| when | whenever | where | wherever | |||

| *which | while | who | whom | whose | ||

* This row contains relative pronouns, which may be punctuated differently.

Joining Independent Clauses

There are three ways to join independent clauses. By using a mix of all three methods and varying your transition words, you will add complexity to your writing and improve the flow. You will also be emphasizing to your reader which ideas you want to connect or to show things like cause and effect or contrast. For a more detailed review of independent clauses, look back at Chapter 3: Putting Ideas into Your Own Words and Paragraphs. Option 1 By simply using a semicolon (;), you can make the ideas connect more than if you were to use a period. If you are trying to reinforce that connection, use a semicolon because it is not as strong of a pause as a period and reinforces the link. Option 2 When you want to link two independent sentences and increase the flow between ideas, you can add a comma and a coordinating conjunction between them. With coordinating conjunctions (FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), you do not use a comma every time: you would only do so if what is on either side of the conjunction is a complete sentence not just a phrase. You would not put a comma if you are only giving a list of two items. For example:

Comma:It is cold outside, so I wore an extra warm coat.

No comma: It is cold outside. I wore an extra warm coat and gloves.

The first example contains a complete sentence (independent clause) on either side of the conjunction so. Just the conjunction by itself or just a comma by itself is not strong enough to join two independent clauses. However, if you put the two together with so, you can link the two. In the second example, and is simply connecting two noun phrases: warm coat and gloves. What comes after the conjunction is not a complete sentence, so you would not add a comma. To check if there is a complete, independent clause, ask yourself, “Can that part stand by itself as a complete sentence?” In the case of the no comma example, gloves is what comes after the comma. That is not a complete sentence, only a noun: that means it is part of a list and is not a complete sentence = no comma. The point of these examples was to show you that you have to be careful how you use commas and conjunctions. As easy as it would be to just always toss in a comma, doing so would confuse your reader as what is and is not part of a list and what ideas are joined. Option 3 Your third choice is to join two independent clauses with a conjunctive adverb or another transition word. These words are very useful because they clearly show your reader how you would like your ideas to connect. If you wanted to emphasize contrasting ideas, you would use on the other hand or however. If you wanted to show cause and effect, you could use as a result. Refer to the tables you have seen in other chapters to make sure you are using the transitions you actually mean to be using; then, check Table 12.2 to confirm how you should punctuate it. After your first independent clause, you can choose to either use a period or a semicolon, again depending on how much of a link you want to show. You may also want to consider how many long sentences you have used prior to this. If you use a lot of complicated sentences, you should probably use a period to allow your reader to take a break. You must also remember to include a comma after the transition word.

Period:It is cold outside.Therefore, I wore an extra warm coat.

Semicolon: It is cold outside; therefore, I wore an extra warm coat.

Joining Dependent Clauses

If one of the clauses in a sentence is independent and can stand on its own, but the other is not, you have to construct the sentence a little differently. Whenever you add a subordinating conjunction or relative pronoun to an independent sentence, you create a dependent clause—one that can never stand alone. In the examples below, notice that when the independent clause comes first, it is strong enough to carry the dependent clause at the end without any helping punctuation. However, if you want the dependent clause first, you must add a comma between it and the independent clause: the dependent clause is not strong enough to support the independent clause after without a little help. In the examples below, the independent clauses are double underlined and the dependent clause has a single underline.

IND first:I wore an extra warm coat as it is cold outside.

DEP first: As it is cold outside, I wore an extra warm coat.

Tip

If you want to start a sentence with Because, you need to make sure there is a second half to that sentence that is independent. A Because (dependent) clause can never stand by itself.

At the bottom on Table 12.2, you can see a list of five dependent markers that can be used a little differently. These are relative pronouns, and when you use them, you need to ask yourself if the information is 100 percent necessary for the reader to understand what you are describing. If it is optional, you can include a comma before the relative clause even if it comes after the independent clause.

Non–essential:As it is cold outside, I wore an extra warm coat, which was blue.

Essential: My coat which is blue is the one I wear when it is really cold outside.

In the non–essential example, the fact that the coat was warm was probably more important than that the coat was blue. The information that the coat is blue probably would not make a difference in keeping the person warm, so the information in that relative clause is not terribly important. Adding the comma before the clause tells the reader it is extra information. In the essential example, the use of the same clause without a preceding comma shows that this information is important. The writer is implying he has other coats that are not as warm and are not blue, so he is emphasizing the importance of the blue coat. These are the only five subordinators, or relative pronouns, for which you can do this; every other one needs to follow the previous explanation of how to use these dependent transition words. If you do decide to add a comma with one of the relative pronouns, you need to think critically about whether or not that description is completely essential.

Using any of these sentence joining strategies is helpful in providing sentence variety to help your reader stay engaged and reading attentively. By following these punctuation rules, you will also avoid creating sentence fragments, run-on sentences, and comma splices, all of which improves your end product.

Given how much work you have put into your research paper, you will want to check for any errors that could distract or confuse your readers. Using the spell checking feature in your word processing program can be helpful, it should not replace a full, careful review of your document. Be sure to check for any errors that may have come up frequently for you in the past. Use Checklist 12.4: Editing Your Writing to help you as you edit.

Checklist 12.4: Editing Your Writing

Grammar

Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

Are some sentences run-on? How can I correct them?

Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

Does every verb agree with its subject?

Is every verb in the correct tense?

Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

Have I used who and whom correctly?

Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to/too/two?

Tip

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Tip

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, classmate, or peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Formatting

Your finished assignment should be properly formatted, following the style required of you. Formatting includes the style of the title, margin size, page number placement, location of the writer’s name, and other factors. Your instructor or department may require a specific style to be used. The requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) style guide, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

Self-practice EXERCISE 12.10

With the help of Checklist 12.4, edit and proofread your essay.

Checking Citations and Formatting

When editing a research paper, it is also important to check that you have cited sources properly and formatted your document according to the specified guidelines. There are two reasons for this. First, citing sources correctly ensures that you give proper credit to other people for ideas and information that helped you in your work. Second, using correct formatting establishes your paper as one student’s contribution to the work developed by and for a larger academic community. Increasingly, American Psychological Association (APA) style guidelines are the standard for many academic fields. Use Checklist 12.5: Citations and Formatting to help.

Checklist 12.5: Citations and Formatting

Within the body of my paper, each fact or idea taken from a source is credited to the correct source.

Each in-text citation includes the source author’s name (or, where applicable, the organization name or source title) and year of publication. I have used the correct format of in text and parenthetical citations.

Each source cited in the body of my paper has a corresponding entry in the references section of my paper.

My references section includes a heading and double-spaced alphabetized entries.

Each entry in my references section is indented on the second line and all subsequent lines.

Each entry in my references section includes all the necessary information for that source type, in the correct sequence and format.

My paper includes a title page.

My paper includes a running head.

The margins of my paper are set at one inch. Text is double spaced and set in a standard 12-point font.

For detailed guidelines on APA citation and formatting, see Chapter 9: Citations and Referencing.

Writing at Work

Following APA citation and formatting guidelines may require time and effort. However, it is good practice for learning how to follow accepted conventions in any professional field. Many large corporations create a style manual with guidelines for editing and formatting documents produced by that corporation. Employees follow the style manual when creating internal documents and documents for publication.

During the process of revising and editing, Jorge made changes in the content and style of his paper. He also gave the paper a final review to check for overall correctness and, particularly, correct APA citations and formatting. Read the final draft of his paper.

With the help of Checklist 12.5, edit and proofread your essay.

Although you probably do not want to look at your paper again before you submit it to your instructor, take the time to do a final check. Since you have already worked through all of the checklists above focusing on certain aspects at one time, working through one final checklist should confirm you have written a strong, persuasive essay and that everything is the way you want it to be. As extra insurance you have produced a strong paper, you may even want someone else to double-check your essay using Checklist 12.6: Final Revision. Then you can compare to see how your perceptions of your paper match those of someone else, essentially having that person act as the one who will be grading your paper.

Checklist 12.6: Final Revision

| First Revision 1: Organization | |

| ___ | Do you show you understand the assignment: purpose, audience, and genre? |

| ___ | Focus: Have you clearly stated your thesis (your controlling idea) in the first paragraph? |

| ___ | Does your thesis statement catch the reader’s attention? |

| ___ | Unity: Write your opening and closing paragraphs and place each topic sentence in between. You should have a “mini essay” with several different main points supporting your thesis. |

| ___ | Are your paragraphs organized in a logical manner? |

| ___ ___ | Does each topic sentence (per paragraph) logically follow the one preceding it? |

| Do you have several points to support your thesis? | |

| ___ ___ ___ | Check whether your paragraphs are organized according to a specific pattern. |

| Would rearranging your paragraphs support your thesis better? | |

| Have you provided a comprehensive conclusion to your essay? Does it summarize your main points (using different words)? | |

| First Revision 2: Paragraphs and Sentences | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ | Does each paragraph have main points and supporting details? |

| Does each paragraph have only one main point? | |

| Is your approach or pattern used to develop your paragraph’s main point followed? | |

| Check that each sentence is relevant to the main point of the paragraph. | |

| Are there several sentences giving details, facts, quotes, reasons, and arguments in each paragraph? | |

| Is each supporting detail specific, concrete, and relevant to the topic sentence? | |

| Does each sentence logically follow the preceding one? | |

| Have you used transitional words to help the reader follow your thoughts? If not, add them. | |

| Paragraph length: If too short, develop further. If too long, break into smaller paragraphs or consolidate some sentences. | |

| Check your essay for tone and point of view. | |

| Second Revision 1: Sentences and Usage | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ | Confirm that each sentence has a subject and a verb. |

| Revise fragments, splices, and run-on sentences. | |

| Check modifiers to see if they have been put in unclear places. | |

| Do you have a variety of sentence structures? (simple and complex) | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ | Scan for subject-verb agreement in each sentence. |

| Are you consistent with your verb tenses? Check to make sure there are not any confusing or irrelevant tense changes. | |

| Make sure that words in lists are in parallel forms. | |

| Think through your pronouns; what is each one referring to? | |

| Check for confusing “person” shifts within paragraphs. Keep the subjects consistent. | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ | Identify all verbs and change any that are passive to active. |

| Use strong verbs not weak adverbs. Say something “is” not that it “may be.” | |

| Check for wordiness. | |

| Scan to make sure you have not used the same word repeatedly in the same sentence and paragraph. Use a thesaurus. | |

| Look for and eliminate clichés. | |

| Second Revision 2: Documentation | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ | Have you documented all your references? |

| Have you used in text citations every time they were needed? Have you formatted all your citations correctly? | |

| Is your references’ section complete and correct according to the JIBC APA Style Guide. | |

| Second Revision 3: Mechanics | |

| ___ ___ | Check that all words and sentences are punctuated according to standard usage. |

| Check for spelling and typographical errors. | |

| Third Revision: Content | |

| ___ ___ ___ ___ | Read your essay aloud. Do you believe what you have written? |

| At this point do you develop your controlling idea in a way that makes sense? | |

| Have you provided enough background information? Is it relevant/necessary? | |

| Have you primarily used paraphrasing as opposed to direct quotations? | |

You should now be confident you have produced a strong argument that is wonderfully constructed and that you will be able to persuade your audience that your points and point of view are valid.

Key Takeaways

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

- Organization in a research paper means that the argument proceeds logically from the introduction to the body to the conclusion. It flows logically from one point to the next. When revising a research paper, evaluate the organization of the paper as a whole and the organization of individual paragraphs.

- In a cohesive research paper, the elements of the paper work together smoothly and naturally. When revising a research paper, evaluate its cohesion. In particular, check that information from research is smoothly integrated with your ideas.

- An effective research paper uses a style and tone that are appropriately academic and serious. When revising a research paper, check that the style and tone are consistent throughout.

- Editing a research paper involves checking for errors in grammar, mechanics, punctuation, usage, spelling, citations, and formatting.