Main Body

Chapter 5. Putting the Pieces Together with a Thesis Statement

5.1 Apply Prewriting Models

Learning Objectives

- Use prewriting strategies to choose a topic and narrow the focus

If you think that a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on the computer screen is a scary sight, you are not alone. Many writers, students, and employees find that beginning to write can be intimidating. When faced with a blank page, however, experienced writers remind themselves that writing, like other everyday activities, is a process. Every process, from writing to cooking to bike riding to learning to use a new cell phone will get significantly easier with practice.

Just as you need a recipe, ingredients, and proper tools to cook a delicious meal, you also need a plan, resources, and adequate time to create a good written composition. In other words, writing is a process that requires steps and strategies to accomplish your goals.

These are the five steps in the writing process:

- Prewriting

- Outlining the structure of ideas

- Writing a rough draft

- Revising

- Editing

Effective writing can be simply described as good ideas that are expressed well and arranged in the proper order. This chapter will give you the chance to work on all these important aspects of writing. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, this chapter covers six: using experience and observations, freewriting, asking questions, brainstorming, mapping, and searching the Internet. Using the strategies in this chapter can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Prewriting

Prewriting is the stage of the writing process during which you transfer your abstract thoughts into more concrete ideas in ink on paper (or in type on a computer screen). Although prewriting techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, the following four strategies are best used when initially deciding on a topic:

Using experience and observations

Reading

Freewriting

Asking questions

At this stage in the writing process, it is okay if you choose a general topic. Later you will learn more prewriting strategies that will narrow the focus of the topic.

Choosing a Topic

In addition to understanding that writing is a process, writers also understand that choosing a good general topic for an assignment is an essential step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about but also fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Mariah as she prepares a piece of writing. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and complete exercises in this chapter.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

Using Experience and Observations

When selecting a topic, you may want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Tip

Have you seen an attention-grabbing story on your local news channel? Many current issues appear on television, in magazines, and on the Internet. These can all provide inspiration for your writing.

Reading

Reading plays a vital role in all the stages of the writing process, but it first figures in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose a topic and also develop that topic. For example, a magazine advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. The cover may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After you choose a topic, critical reading is essential to the development of a topic. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about the main idea and the support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting, remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

Tip

The steps in the writing process may seem time consuming at first, but following these steps will save you time in the future. The more you plan in the beginning by reading and using prewriting strategies, the less time you may spend writing and editing later because your ideas will develop more swiftly.

Prewriting strategies depend on your critical reading skills. Reading prewriting exercises (and outlines and drafts later in the writing process) will further develop your topic and ideas. As you continue to follow the writing process, you will see how Mariah uses critical reading skills to assess her own prewriting exercises.

Freewriting

Freewriting is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually three to five minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over until you come up with a new thought.

Writing often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Remember, to generate ideas in your freewriting, you may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

Look at Mariah’s example. The instructor allowed the members of the class to choose their own topics, and Mariah thought about her experiences as a communications major. She used this freewriting exercise to help her generate more concrete ideas from her own experience.

Tip

Some prewriting strategies can be used together. For example, you could use experience and observations to come up with a topic related to your course studies. Then you could use freewriting to describe your topic in more detail and figure out what you have to say about it.

Self-practice Exercise 5.1

Take another look at the possible topics for your expository essay assignment then freewrite about that topic. Write without stopping for five minutes. After you finish, read over what you wrote. How well do you think you will be able to develop this topic?

Possible expository essay questions:

Narrative: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized narrative essay.

Your first day of post-secondary school

A moment of success or failure

An experience that helped you mature

Illustration: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized illustration essay.

The media and the framing of crime

Child obesity

The effect of violent video games on behaviour

Description: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized description essay.

How to reduce weight

How to remain relevant in your workplace

How to get a good night’s sleep

Classification: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized classification essay.

Ways of boring people

Methods of studying for a final exam

Extreme weather

Process analysis: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized process analysis essay.

How to complain effectively

How to apply the Heimlich manoeuvre or other lifesaving technique

How a particular accident occurred

Definition: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized definition essay.

Right to privacy

Integrity

Heroism

Compare and contrast: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized compare and contrast essay.

Two ways of losing weight: one healthy, one dangerous

Two ways to break a bad habit

An active and a passive student

Cause and effect: Choose one of the topics below and relate your ideas in a clearly organized cause and effect essay.

Plagiarism and cheating in school. Give its effects.

Bullying. Give its effects.

A personal, unreasonable fear or irritation. Give its causes.

Asking Questions

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? In everyday situations, you pose these kinds of questions to get information. Who will be my partner for the project? When is the next meeting? Why is my car making that odd noise?

You seek the answers to these questions to gain knowledge, to better understand your daily experiences, and to plan for the future. Asking these types of questions will also help you with the writing process. As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

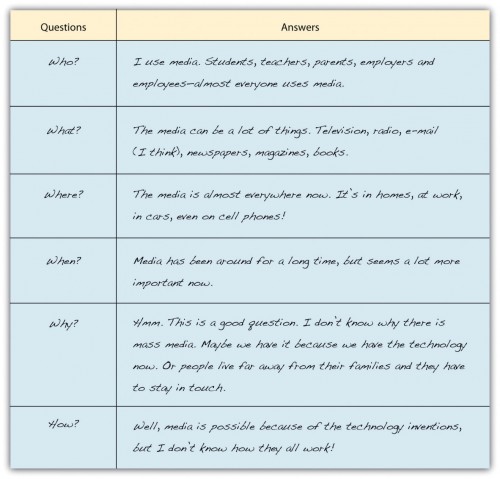

When Mariah reread her freewriting notes, she found she had rambled and her thoughts were disjointed. She realized that the topic that interested her most was the one she started with: the media. She then decided to explore that topic by asking herself questions about it. Her purpose was to refine media into a topic she felt comfortable writing about. To see how asking questions can help you choose a topic, take a look at the following chart in Figure 5.1: Asking Questions that Mariah completed to record her questions and answers. She asked herself the questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories. The questions are often called the 5WH questions, after their initial letters.

Tip

Prewriting is very purpose driven; it does not follow a set of hard and fast rules. The purpose of prewriting is to find and explore ideas so that you will be prepared to write. A prewriting technique like asking questions can help you both find a topic and explore it. The key to effective prewriting is to use the techniques that work best for your thinking process. Freewriting may not seem to fit your thinking process, but keep an open mind. It may work better than you think. Perhaps brainstorming a list of topics might better fit your personal style. Mariah found freewriting and asking questions to be fruitful strategies to use. In your own prewriting, use the 5WH questions in any way that benefits your planning.

Self-practice Exercise 5.2

Using the prewriting you completed in Self–Practice Exercise 5.1,read each question and use your own paper to answer the 5WH questions. As with Mariah when she explored her writing topic for more detail, it is okay if you do not know all the answers. If you do not know an answer, use your own opinion to speculate, or guess. You may also use factual information from books or articles you previously read on your topic. Later in the chapter, you will read about additional ways (like searching the Internet) to answer your questions and explore your guesses.

5WH Questions

Who?

_____________________________________________________

What?

_____________________________________________________

Where?

_____________________________________________________

When?

_____________________________________________________

Why?

_____________________________________________________

How?

_____________________________________________________

Now that you have completed some of the prewriting exercises, you may feel less anxious about starting a paper from scratch. With some ideas down on paper (or saved on a computer), writers are often more comfortable continuing the writing process. After identifying a good general topic, you, too, are ready to continue the process.

Tip

You may find that you need to adjust your topic as you move through the writing stages (and as you complete the exercises in this chapter). If the topic you have chosen is not working, you can repeat the prewriting activities until you find a better one.

More Prewriting Techniques: Narrowing the Focus

The prewriting techniques of freewriting and asking questions helped Mariah think more about her topic. The following additional prewriting strategies would help her (and you) narrow the focus of the topic:

Brainstorming

Idea mapping

Searching the Internet

Narrowing the focus means breaking up the topic into subtopics, or more specific points. Generating a lot of subtopics helps in selecting the ones that fit the assignment and appeal to the writer and the audience.

After rereading her syllabus, Mariah realized her general topic, mass media, was too broad for her class’s short paper requirement. Three pages would not be enough to cover all the concerns in mass media today. Mariah also realized that although her readers are other communications majors who are interested in the topic, they may want to read a paper about a particular issue in mass media.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is similar to list making. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer document) and write your general topic across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of more specific ideas. Think of your general topic as a broad category and the list items as things that fit into that category. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic.

The following is Mariah’s brainstorming list:

From this list, Mariah could narrow her focus to a particular technology under the broad category of mass media.

Writing at Work

Imagine you have to write an email to your current boss explaining your prior work experience, but you do not know where to start. Before you begin the email, you can use the brainstorming technique to generate a list of employers, duties, and responsibilities that fall under the general topic of work experience.

Idea Mapping

Idea mapping allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic in a circle in the centre of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

Mariah tried idea mapping in addition to brainstorming. Figure 5.2: Idea Map shows what she created.

Figure 5.2 Idea Map

Notice Mariah’s largest circle contains her general topic: mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Mariah drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Mariah to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy.

From this idea map, Mariah saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Searching the Internet

Using search engines on the Internet is a good way to see what kinds of websites are available on your topic. Writers use search engines not only to understand more about the topic’s specific issues but also to get better acquainted with their audience.

Tip

Look back at the chart you completed in Self Practice Exercise 5.2. Did you guess at any of the answers? Searching the Internet may help you find answers to your questions and confirm your guesses. Be choosy about the websites you use. Make sure they are reliable sources for the kind of information you seek.

When you search the Internet, type some key words from your broad topic or words from your narrowed focus into your browser’s search engine (many good general and specialized search engines are available for you to try). Then look over the results for relevant and interesting articles.

Results from an Internet search show writers the following information:

Who is talking about the topic

How the topic is being discussed

What specific points are currently being discussed about the topic

Tip

If the search engine results are not what you are looking for, revise your key words and search again. Some search engines also offer suggestions for related searches that may give you better results.

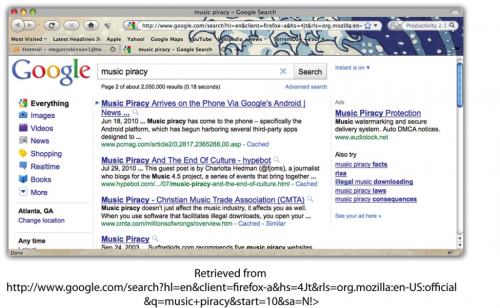

Mariah typed the words music piracy from her idea map into the search engine Google (see Figure 5.3 Useful Search Engine Results).

Figure 5.3 Useful Search Engine Results

Note: Not all the results online search engines return will be useful or reliable. Carefully consider the reliability of an online source before selecting a topic based on it. Remember that factual information can be verified in other sources, both online and in print. If you have doubts about any information you find, either do not use it or identify it as potentially unreliable.

The results from Mariah’s search included websites from university publications, personal blogs, online news sources, and a lot of legal cases sponsored by the recording industry. Reading legal jargon made Mariah uncomfortable with the results, so she decided to look further. Reviewing her map, she realized that she was more interested in consumer aspects of mass media, so she refocused her search to media technology and the sometimes confusing array of expensive products that fill electronics stores. Now, Mariah considers a topic on the products that have fed the mass media boom in everyday lives.

Self-practice Exercise 5.3

In Self–Practice Exercise 5.2, you chose a possible topic and explored it by answering questions about it using the 5WH questions. However, this topic may still be too broad. Here, in this exercise, choose and complete one of the prewriting strategies to narrow the focus. Use brainstorming, idea mapping, or searching the Internet.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Share what you found and what interests you about the possible topic(s).

Prewriting strategies are a vital first step in the writing process. First they help you first choose a broad topic, and then they help you narrow the focus of the topic to a more specific idea. Use Checklist 5.1: Topic Checklist to help you with this step.

Checklist 5.1 Developing a Good Topic

Using this checklist can help you decide if your narrowed topic is a good topic for your assignment.

Am I interested in this topic?

Would my audience be interested?

Do I have prior knowledge or experience with this topic? If so, would I be comfortable exploring this topic and sharing my experiences?

Do I want to learn more about this topic?

Is this topic specific?

Does it fit the length of the assignment?

An effective topic ensures that you are ready for the next step. With your narrowed focus in mind, answer the bulleted questions in the checklist for developing a good topic. If you can answer “yes” to all the questions, write your topic on the line below. If you answer “no” to any of the questions, think about another topic or adjust the one you have and try the prewriting strategies again.

My narrowed topic: ____________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- All writers rely on steps and strategies to begin the writing process.

- The steps in the writing process are prewriting, outlining, writing a rough draft, revising, and editing.

- Prewriting is the transfer of ideas from abstract thoughts into words, phrases, and sentences on paper.

- A good topic interests the writer, appeals to the audience, and fits the purpose of the assignment.

- Writers often choose a general topic first and then narrow the focus to a more specific topic.

5.2 Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Develop a strong, clear thesis statement with the proper elements

- Revise your thesis statement

Have you ever known someone who was not very good at telling stories? You probably had trouble following the train of thought as the storyteller jumped from point to point, either being too brief in places that needed further explanation or providing too many details on a meaningless element. Maybe the person told the end of the story first, then moved to the beginning and later added details to the middle. The ideas were probably scattered, and the story did not flow very well. When the story was over, you probably had many questions.

Just as a personal anecdote can be a disorganized mess, an essay can fall into the same trap of being out of order and confusing. That is why writers need a thesis statement to provide a specific focus for their essay and to organize what they are about to discuss in the body.

Just like a topic sentence summarizes a single paragraph, the thesis statement summarizes an entire essay. It tells the reader the point you want to make in your essay, while the essay itself supports that point. It is like a signpost that signals the essay’s destination. You should form your thesis before you begin to organize an essay, but you may find that it needs revision as the essay develops.

Elements of a Thesis Statement

For every essay you write, you must focus on a central idea. This idea stems from a topic you have chosen or been assigned or from a question your teacher has asked. It is not enough merely to discuss a general topic or simply answer a question with a yes or no. You have to form a specific opinion, and then articulate that into a controlling idea—the main idea upon which you build your thesis.

Remember that a thesis is not the topic itself, but rather your interpretation of the question or subject. For whatever topic your instructor gives you, you must ask yourself, “What do I want to say about it?” Asking and then answering this question is vital to forming a thesis that is precise, forceful, and confident.

A thesis is one sentence long and appears toward the end of your introduction. It is specific and focuses on one to three points of a single idea—points that are able to be demonstrated in the body. It forecasts the content of the essay and suggests how you will organize your information. Remember that a thesis statement does not summarize an issue but rather dissects it.

A Strong Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement contains the following qualities:

Specificity: A thesis statement must concentrate on a specific area of a general topic. As you may recall, the creation of a thesis statement begins when you choose a broad subject and then narrow down its parts until you pinpoint a specific aspect of that topic. For example, health care is a broad topic, but a proper thesis statement would focus on a specific area of that topic, such as options for individuals without health care coverage.

Precision: A strong thesis statement must be precise enough to allow for a coherent argument and to remain focused on the topic. If the specific topic is options for individuals without health care coverage, then your precise thesis statement must make an exact claim about it, such as that limited options exist for those who are uninsured by their employers. You must further pinpoint what you are going to discuss regarding these limited effects, such as whom they affect and what the cause is.

Arguability: A thesis statement must present a relevant and specific argument. A factual statement often is not considered arguable. Be sure your thesis statement contains a point of view that can be supported with evidence.

Demonstrability: For any claim you make in your thesis, you must be able to provide reasons and examples for your opinion. You can rely on personal observations in order to do this, or you can consult outside sources to demonstrate that what you assert is valid. A worthy argument is backed by examples and details.

Forcefulness/Assertiveness: A thesis statement that is forceful shows readers that you are, in fact, making an argument. The tone is assertive and takes a stance that others might oppose.

Confidence: In addition to using force in your thesis statement, you must also use confidence in your claim. Phrases such as I feel or I believe actually weaken the readers’ sense of your confidence because these phrases imply that you are the only person who feels the way you do. In other words, your stance has insufficient backing. Taking an authoritative stance on the matter persuades your readers to have faith in your argument and open their minds to what you have to say.

Tip

Even in a personal essay that allows the use of first person, your thesis should not contain phrases such as in my opinion or I believe. These statements reduce your credibility and weaken your argument. Your opinion is more convincing when you use a firm attitude.

Self-practice Exercise 5.4

On a sheet of paper, write a thesis statement for each of the following topics. Remember to make each statement specific, precise, demonstrable, forceful and confident.

Topics

Texting while driving

The legal drinking age in different provinces of Canada

Steroid use among professional athletes

Abortion

Racism

Examples of Appropriate Thesis Statements

Each of the following thesis statements meets several of the qualities discussed above: specificity, precision, arguability, demonstrability, forcefulness/assertiveness, and confidence.

The societal and personal struggles of Floyd in the play Where the Blood Mixes, by Kevin Loring, symbolize the challenge of First Nations people of Canada who lived through segregation and placement into residential schools.

Closing all American borders for a period of five years is one solution that will tackle illegal immigration.

Shakespeare’s use of dramatic irony in Romeo and Juliet spoils the outcome for the audience and weakens the plot.

J. D. Salinger’s character in Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield, is a confused rebel who voices his disgust with phonies, yet in an effort to protect himself, he acts like a phony on many occasions.

Compared to an absolute divorce, no-fault divorce is less expensive, promotes fairer settlements, and reflects a more realistic view of the causes for marital breakdown.

Exposing children from an early age to the dangers of drug abuse is a sure method of preventing future drug addicts.

In today’s crumbling job market, a high school diploma is not significant enough education to land a stable, lucrative job.

Tip

You can find thesis statements in many places, such as in the news; in the opinions of friends, co-workers or teachers; and even in songs you hear on the radio. Become aware of thesis statements in everyday life by paying attention to people’s opinions and their reasons for those opinions. Pay attention to your own everyday thesis statements as well, as these can become material for future essays.

Now that you have read about the contents of a good thesis statement and have seen examples, take a look four pitfalls to avoid when composing your own thesis.

A thesis is weak when it is simply a declaration of your subject or a description of what you will discuss in your essay. Weak thesis statement: My paper will explain why imagination is more important than knowledge.

A thesis is weak when it makes an unreasonable or outrageous claim or insults the opposing side. Weak thesis statement: Religious radicals across the country are trying to legislate their puritanical beliefs by banning required high school books.

A thesis is weak when it contains an obvious fact or something that no one can disagree with or provides a dead end. Weak thesis statement: Advertising companies use sex to sell their products.

A thesis is weak when the statement is too broad. Weak thesis statement: The life of Pierre Trudeau was long and accomplished.

Self-practice Exercise 5.5

Read the following thesis statements. On a piece of paper, identify each as weak or strong. For those that are weak, list the reasons why. Then revise the weak statements so that they conform to the requirements of a strong thesis.

The subject of this paper is my experience with ferrets as pets.

The government must expand its funding for research on renewable energy resources in order to prepare for the impending end of oil.

Edgar Allan Poe was a poet who lived in Baltimore during the 19th century.

In this essay, I will give you a lot of reasons why marijuana should not be legalized in British Columbia.

Because many children’s toys have potential safety hazards that could lead to injury, it is clear that not all children’s toys are safe.

My experience with young children has taught me that I want to be a disciplinary parent because I believe that a child without discipline can be a parent’s worst nightmare.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

Often in your career, you will need to ask your boss for something through an email. Just as a thesis statement organizes an essay, it can also organize your email request. While your email will be shorter than an essay, using a thesis statement in your first paragraph quickly lets your boss know what you are asking for, why it is necessary, and what the benefits are. In short body paragraphs, you can provide the essential information needed to expand upon your request.

Writing a Thesis Statement

One legitimate question readers always ask about a piece of writing is “What is the big idea?” (You may even ask this question when you are the reader, critically reading an assignment or another document.) Every nonfiction writing task—from the short essay to the 10-page term paper to the lengthy senior thesis—needs a big idea, or a controlling idea, as the “spine” for the work. The controlling idea is the main idea that you want to present and develop.

Tip

For a longer piece of writing, the main idea should be broader than the main idea for a shorter piece of writing. Be sure to frame a main idea that is appropriate for the length of the assignment. Ask yourself how many pages it will take to explain and explore the main idea in detail? Be reasonable with your estimate. Then expand or trim it to fit the required length.

The big idea, or controlling idea, you want to present in an essay is expressed in your thesis statement. Remember that a thesis statement is often one sentence long, and it states your point of view. The thesis statement is not the topic of the piece of writing but rather what you have to say about that topic and what is important to tell readers.

Look at Table 5.1: Topics and Thesis Statements for a comparison of topics and thesis statements.

Table 5.1 Topics and Thesis Statements: A Comparison

| Topic | Thesis Statement |

| Music piracy | The recording industry fears that so-called music piracy will diminish profits and destroy markets, but it cannot be more wrong. |

| The number of consumer choices available in media gear | Everyone wants the newest and the best digital technology, but the choices are extensive, and the specifications are often confusing. |

| E-books and online newspapers increasing their share of the market | E-books and online newspapers will bring an end to print media as we know it. |

| Online education and the new media | Someday, students and teachers will send avatars to their online classrooms. |

The first thesis statement you write will be a preliminary thesis statement, or a working thesis statement. You will need it when you begin to outline your assignment as a way to organize it. As you continue to develop the arrangement, you can limit your working thesis statement if it is too broad or expand it if it proves too narrow for what you want to say.

Self-practice exercise 5.6

Using the topic you selected in Self–Practice Exercise 5.3,develop a working thesis statement that states your controlling idea for the piece of writing you are doing. On a sheet of paper, write your working thesis statement.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Tip

You will make several attempts before you devise a working thesis statement that you think is effective. Each draft of the thesis statement will bring you closer to the wording that expresses your meaning exactly.

Revising a Thesis Statement

Your thesis will probably change as you write, so you will need to modify it to reflect exactly what you have discussed in your essay. Remember, you begin with a working thesis statement, an indefinite statement that you make about your topic early in the writing process for the purpose of planning and guiding your writing.

Working thesis statements often become stronger as you gather information and form new opinions and reasons for those opinions. Revision helps you strengthen your thesis so that it matches what you have expressed in the body of the paper.

Tip

The best way to revise your thesis statement is to ask questions about it and then examine the answers to those questions. By challenging your own ideas and forming definite reasons for those ideas, you grow closer to a more precise point of view, which you can then incorporate into your thesis statement.

You can cut down on irrelevant aspects and revise your thesis by taking the following steps:

Pinpoint and replace all nonspecific words, such as people, everything, society, or life, with more precise words in order to reduce any vagueness.

Working thesis: Young people have to work hard to succeed in life.

Revised thesis: Recent college graduates must have discipline and persistence in order to find and maintain a stable job in which they can use and be appreciated for their talents.

The revised thesis makes a more specific statement about success and what it means to work hard. The original includes too broad a range of people and does not define exactly what success entails. By replacing the general words like people and work hard, the writer can better focus his or her research and gain more direction in his or her writing.

Clarify ideas that need explanation by asking yourself questions that narrow your thesis.

Working thesis: The welfare system is a joke.

Revised thesis: The welfare system keeps a socioeconomic class from gaining employment by alluring members of that class with unearned income, instead of programs to improve their education and skill sets.

Joke means many things to many people. Readers bring all sorts of backgrounds and perspectives to the reading process and would need clarification for a word so vague. This expression may also be too informal for the selected audience. By asking questions, the writer can devise a more precise and appropriate explanation for joke. The writer should ask questions similar to the 5WH questions. By incorporating the answers to these questions into a thesis statement, the writer more accurately defines his or her stance, which will better guide the writing of the essay.

Replace any linking verbs with action verbs. Linking verbs gives information about the subject, such as a condition or relationship (is, appear, smell, sound), but they do not show any action. The most common linking verb is any forms of the verb to be, a verb that simply states that a situation exists.

Working thesis: British Columbian schoolteachers are not paid enough.

Revised thesis: The legislature of British Columbia cannot afford to pay its educators, resulting in job cuts and resignations in a district that sorely needs highly qualified and dedicated teachers.

The linking verb in this working thesis statement is the word are. Linking verbs often make thesis statements weak because they do not express action. Reading the original thesis statement above, readers might wonder why teachers are not paid enough, but the statement does not compel them to ask many more questions. The writer should ask him- or herself questions in order to replace the linking verb with an action verb, thus forming a stronger thesis statement, one that takes a more definitive stance on the issue. For example, the writer could ask:

Who is not paying the teachers enough?

What is considered “enough”?

What is the problem?

What are the results

4. Omit any general claims that are hard to support.

Working thesis: Today’s teenage girls are too sexualized.

Revised thesis: Teenage girls who are captivated by the sexual images on MTV are conditioned to believe that a woman’s worth depends on her sensuality, a feeling that harms their self-esteem and behaviour.

It is true that some young women in today’s society are more sexualized than in the past, but that is not true for all girls. Many girls have strict parents, dress appropriately, and do not engage in sexual activity while in middle school and high school. The writer of this thesis should ask the following questions:

Which teenage girls?

What constitutes “too” sexualized?

Why are they behaving that way?

Where does this behaviour show up?

What are the repercussions?

Self-practice exercise 5.7

In Section 5.1, you determined your purpose for writing and your audience. You then completed a freewriting exercise on one of the topics presented to you. Using that topic, you then narrowed it down by answering the 5WH questions. After you answered these questions, you chose one of the three methods of prewriting and gathered possible supporting points for your working thesis statement.

Now, on a sheet of paper, write your working thesis statement. Identify any weaknesses in this sentence and revise the statement to reflect the elements of a strong thesis statement. Make sure it is specific, precise, arguable, demonstrable, forceful, and confident.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

In your career you may have to write a project proposal that focuses on a particular problem in your company, such as reinforcing the tardiness policy. The proposal would aim to fix the problem; using a thesis statement would clearly state the boundaries of the problem and the goals of the project. After writing the proposal, you may find that the thesis needs revising to reflect exactly what is expressed in the body. The techniques from this chapter would apply to revising that thesis.

Key Takeaways

- Proper essays require a thesis statement to provide a specific focus and suggest how the essay will be organized.

- A thesis statement is your interpretation of the subject, not the topic itself.

- A strong thesis is specific, precise, forceful, confident, and is able to be demonstrated.

- A strong thesis challenges readers with a point of view that can be debated and supported with evidence.

- A weak thesis is simply a declaration of your topic or contains an obvious fact that cannot be argued.

- Depending on your topic, it may or may not be appropriate to use first person point of view.

- Revise your thesis by ensuring all words are specific, all ideas are exact, and all verbs express action.

5.3 Outlining

Learning Objectives

- Identify the steps in constructing an outline

- Construct a topic outline and a sentence outline

Your prewriting activities and readings have helped you gather information for your assignment. The more you sort through the pieces of information you found, the more you will begin to see the connections between them. Patterns and gaps may begin to stand out. But only when you start to organize your ideas will you be able to translate your raw insights into a form that will communicate meaning to your audience.

Tip

Longer papers require more reading and planning than shorter papers do. Most writers discover that the more they know about a topic, the more they can write about it with intelligence and interest.

Organizing Ideas

When you write, you need to organize your ideas in an order that makes sense. The writing you complete in all your courses exposes how analytically and critically your mind works. In some courses, the only direct contact you may have with your instructor is through the assignments you write for the course. You can make a good impression by spending time ordering your ideas.

Order refers to your choice of what to present first, second, third, and so on in your writing. The order you pick closely relates to your purpose for writing that particular assignment. For example, when telling a story, it may be important to first describe the background for the action. Or you may need to first describe a 3-D movie projector or a television studio to help readers visualize the setting and scene. You may want to group your supporting ideas effectively to convince readers that your point of view on an issue is well reasoned and worthy of belief.

In longer pieces of writing, you may organize different parts in different ways so that your purpose stands out clearly and all parts of the essay work together to consistently develop your main point.

Methods of Organizing Writing

The three common methods of organizing writing are chronological order, spatial order, and order of importance, which you learned about in Chapter 4: What Are You Writing, to Whom, and How? You need to keep these methods of organization in mind as you plan how to arrange the information you have gathered in an outline. An outline is a written plan that serves as a skeleton for the paragraphs you write. Later, when you draft paragraphs in the next stage of the writing process, you will add support to create “flesh” and “muscle” for your assignment.

When you write, your goal is not only to complete an assignment but also to write for a specific purpose—perhaps to inform, to explain, to persuade, or a combination of these purposes. Your purpose for writing should always be in the back of your mind, because it will help you decide which pieces of information belong together and how you will order them. In other words, choose the order that will most effectively fit your purpose and support your main point.

Table 5.2: Order versus Purpose shows the connection between order and purpose.

Table 5.2 Order versus Purpose

| Order | Purpose |

| Chronological Order | To explain the history of an event or a topic |

| To tell a story or relate an experience | |

| To explain how to do or make something | |

| To explain the steps in a process | |

| Spatial Order | To help readers visualize something as you want them to see it |

| To create a main impression using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound) | |

| Order of Importance | To persuade or convince |

| To rank items by their importance, benefit, or significance | |

Writing an Outline

For an essay question on a test or a brief oral presentation in class, all you may need to prepare is a short, informal outline in which you jot down key ideas in the order you will present them. This kind of outline reminds you to stay focused in a stressful situation and to include all the good ideas that help you explain or prove your point. For a longer assignment, like an essay or a research paper, many instructors will require you to submit a formal outline before writing a major paper as a way of making sure you are on the right track and are working in an organized manner. The expectation is you will build your paper based on the framework created by the outline.

When creating outlines, writers generally go through three stages: a scratch outline, an informal or topic outline, and a formal or sentence outline. The scratch outline is basically generated by taking what you have come up with in your freewriting process and organizing the information into a structure that is easy for you to understand and follow (for example, a mind map or hierarchical outline). An informal outline goes a step further and adds topic sentences, a thesis, and some preliminary information you have found through research. A formal outline is a detailed guide that shows how all your supporting ideas relate to each other. It helps you distinguish between ideas that are of equal importance and ones that are of lesser importance. If your instructor asks you to submit an outline for approval, you will want to hand in one that is more formal and structured. The more information you provide for your instructor, the better he or she will be able to see the direction in which you plan to go for your discussion and give you better feedback.

Tip

Instructors may also require you to submit an outline with your final draft to check the direction and logic of the assignment. If you are required to submit an outline with the final draft of a paper, remember to revise it to reflect any changes you made while writing the paper.

There are two types of formal outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline. You format both types of formal outlines in the same way.

Place your introduction and thesis statement at the beginning, under Roman numeral I.

Use Roman numerals (II, III, IV, V, etc.) to identify main points that develop the thesis statement.

Use capital letters (A, B, C, D, etc.) to divide your main points into parts.

Use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) if you need to subdivide any As, Bs, or Cs into smaller parts.

End with the final Roman numeral expressing your idea for your conclusion.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

1) Introduction

Thesis statement

2) Main point 1 →becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

- Supporting detail →becomes a support sentence of body paragraph 1

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting detail

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting detail

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

3) Main point 2 →becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2 [same use of subpoints as with Main point 1]

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

4) Main point 3 →becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3[same use of subpoints as with Main points 1&2]

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

5) Conclusion

Tip

In an outline, any supporting detail can be developed with subpoints. For simplicity, the model shows subpoints only under the first main point.

Tip

Formal outlines are often quite rigid in their organization. As many instructors will specify, you cannot subdivide one point if it is only one part. For example, for every Roman numeral I, there needs to be an A. For every A, there must be a B. For every Arabic numeral 1, there must be a 2. See for yourself on the sample outlines that follow.

Constructing Informal or Topic Outlines An informal topic outline is the same as a sentence outline except you use words or phrases instead of complete sentences. Words and phrases keep the outline short and easier to comprehend. All the headings, however, must be written in parallel structure.

Here is the informal topic outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing. Her purpose is to inform, and her audience is a general audience of her fellow college students. Notice how Mariah begins with her thesis statement. She then arranges her main points and supporting details in outline form using short phrases in parallel grammatical structure.

Checklist 5.2 Writing an Effective Topic Outline

This checklist can help you write an effective topic outline for your assignment. It will also help you discover where you may need to do additional reading or prewriting.

Do I have a controlling idea that guides the development of the entire piece of writing?

Do I have three or more main points that I want to make in this piece of writing? Does each main point connect to my controlling idea?

Is my outline in the best order—chronological order, spatial order, or order of importance—for me to present my main points? Will this order help me get my main point across?

Do I have supporting details that will help me inform, explain, or prove my main points?

Do I need to add more support? If so, where?

Do I need to make any adjustments in my working thesis statement before I consider it the final version?

Writing at Work

Word processing programs generally have an automatic numbering feature that can be used to prepare outlines. This feature automatically sets indents and lets you use the tab key to arrange information just as you would in an outline. Although in business this style might be acceptable, in college or university your instructor might have different requirements. Teach yourself how to customize the levels of outline numbering in your word processing program to fit your instructor’s preferences.

Self-practice Exercise 5.8

Using the working thesis statement you wrote in Self–Practice Exercise 5.3 and the reading you did in Section 5.1: Apply Prewriting Models, construct a topic outline for your essay. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and Arabic numerals and capital letters.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your outline. Point out areas of interest from your classmate’s outline and what you would like to learn more about.

Self-practice Exercise 5.9

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Constructing Formal or Sentence Outlines

A sentence outline is the same as a topic outline except you use complete sentences instead of words or phrases. Complete sentences create clarity and can advance you one step closer to a draft in the writing process.

Here is the formal sentence outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing.

Tip

The information compiled under each Roman numeral will become a paragraph in your final paper. Mariah’s outline follows the standard five-paragraph essay arrangement, but longer essays will require more paragraphs and thus more Roman numerals. If you think that a paragraph might become too long, add an additional paragraph to your outline, renumbering the main points appropriately.

Tip

As you are building on your previously created outlines, avoid saving over the previous version; instead, save the revised outline under a new file name. This way you will still have a copy of the original and any earlier versions in case you want to look back at them.

Writing at Work

PowerPoint presentations, used both in schools and in the workplace, are organized in a way very similar to formal outlines. PowerPoint presentations often contain information in the form of talking points that the presenter develops with more details and examples than are contained on the PowerPoint slide.

Self-practice Exercise 5.10

Expand the topic outline you prepared in Self–Practice Exercise 5.7 to make it a sentence outline. In this outline, be sure to include multiple supporting points for your main topic even if your topic outline does not contain them. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and Arabic numerals and capital letters.

Key Takeaways

- Writers must put their ideas in order so the assignment makes sense. The most common orders are chronological order, spatial order, and order of importance.

- After gathering and evaluating the information you found for your essay, the next step is to write a working, or preliminary, thesis statement.

- The working thesis statement expresses the main idea you want to develop in the entire piece of writing. It can be modified as you continue the writing process.

- Effective writers prepare a formal outline to organize their main ideas and supporting details in the order they will be presented.

- A topic outline uses words and phrases to express the ideas.

- A sentence outline uses complete sentences to express the ideas.

- The writer’s thesis statement begins the outline, and the outline ends with suggestions for the concluding paragraph.

5.4 Organizing Your Writing

Learning Objectives

- Understand how and why organizational techniques help writers and readers stay focussed

- Assess how and when to use chronological order to organize an essay

- Recognize how and when to use order of importance to organize an essay

- Determine how and when to use spatial order to organize an essay

The method of organization you choose for your essay is just as important as its content. Without a clear organizational pattern, your reader could become confused and lose interest. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay. Choosing your organizational pattern before you outline ensures that each body paragraph works to support and develop your thesis.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

Chronological order

Order of importance

Spatial order

When you begin to draft your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to help process and accept them.

A solid organizational pattern gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your draft. Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. Planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research.

Chronological Order

In Chapter 4: What Are You Writing, to Whom, and How?, you learned that chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

To explain the history of an event or a topic

To tell a story or relate an experience

To explain how to do or to make something

To explain the steps in a process.

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing, which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first, second, then, after that, later, and finally. These transitional words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first, then, next, and so on.

Writing at Work

At some point in your career you may have to file a complaint with your human resources department. Using chronological order is a useful tool in describing the events that led up to your filing the grievance. You would logically lay out the events in the order that they occurred using the key transitional words. The more logical your complaint, the more likely you will be well received and helped.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

Writing essays containing heavy research

Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

Tip

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

Self-practice Exercise 5.11

On a sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first, second,then, and finally.

Order of Importance

Recall from Chapter 4: What Are You Writing, to Whom, and How? that order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

Persuading and convincing

Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly, almost as importantly, just as importantly, and finally.

Writing at Work

During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

Self-practice Exercise 5.12

On a sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, filmmaking, and so on. Your paragraph should be built on the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

Spatial Order

As stated in Chapter 4: What Are You Writing, to Whom, and How?, spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, whose perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

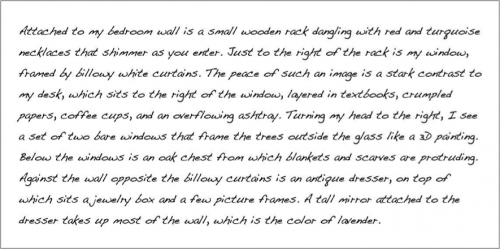

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transitional words and phrases to include when using spatial order:

| Just to the left or just to the right | Behind |

| Between | On the left or on the right |

| Across from | A little further down |

| To the south, to the east, and so on | A few yards away |

| Turning left or turning right | |

Self-practice Exercise 5.13

On a sheet of paper, write a paragraph using spatial order that describes your commute to work, school, or another location you visit often.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Self-practice Exercise 5.14

Look back at your outline from Self–Practice Exercise 5.9. Please share your formal sentence outline with a classmate and together evaluate whether you have organized your points chronologically, by order of importance, or spatially. Discuss if you have organized your paragraphs in the most appropriate and logical way.

In the next chapter, you will build on this formal sentence outline to create a draft and develop your ideas further. Do not worry; you are not expected to have a completed paper at this point. You will be expanding on your sentences to form paragraphs and complete, well-developed ideas.

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression.

Supplemental Exercises

On a separate sheet of paper, choose one of the examples of a proper thesis statement from this chapter (one that interests you) and form three supporting points for that statement. After you have formed your three points, write a topic sentence for each body paragraph. Make sure that your topic sentences can be backed up with examples and details.

Group activity. Choose one of the topics from Self-Practice Exercise 5.4 and form a yes/no question about that topic. Then, take a survey of the people in your class to find out how they feel about the subject. Using the majority vote, ask those people to write on slips of paper the reasons for their opinion. Using the data you collect, form a thesis statement based on your classmates’ perspectives on the topic and their reasons.

On a separate sheet of a paper, write an introduction for an essay based on the thesis statement from the group activity using the techniques for introductory paragraphs that you learned in this chapter.

Start a journal in which you record “spoken” thesis statements. Start listening closely to the opinions expressed by your teachers, classmates, friends, and family members. Ask them to provide at least three reasons for their opinion and record them in the journal. Use this as material for future essays.

Open a magazine and read a lengthy article. See if you can pinpoint the thesis statement as well as the topic sentence for each paragraph and its supporting details.

Journal entry #5

Write two to three paragraphs responding to the following.

Think back to times when you had to write a paper and perhaps struggled to get started. What did you learn this week that you will apply in future assignments to get the ideas flowing?

Reflect on all of the content you have learned so far. What did you find challenging but are now more confident with? What, if anything, still confuses you or you know you need to practice more? How have your study skills, time management, and overall writing improved over the past month?

Remember as mentioned in the Assessment Descriptions in your syllabus:

You will be expected to respond to the questions by reflecting on and discussing your experiences with the week’s material.

When writing your journals, you should focus on freewriting—writing without (overly) considering formal writing structures—but remember that it will be read by the instructor, who needs to be able to understand your ideas.

Your instructor will be able to see if you have completed this entry by the end of the week but will not read all of the journals until next week.