Section 1: Introduction to Indigenous Peoples

Métis

In the 17th and 18th centuries, many French and Scottish men migrated to Canada to work in the fur trade with the Hudson’s Bay Company or the North West Company, or as independent traders. Some had children with First Nations women and formed new communities. The French mixed families and their descendants were most often referred to as “Métis” (from the French word for “to mix”). The Scottish mixed families and their descendants were referred to as “half-breeds.” Today the term half-breed is considered offensive and is no longer used.

Frequently asked questions about the Métis

Who are the Métis?

The Métis are one of the “aboriginal peoples of Canada” identified in Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982. The Métis are people who are Indigenous and do not identify as First Nations or Inuit. The Métis National Council defines “Métis” as a person who “self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Indigenous peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.”

Chris Anderson, professor of Native Studies at the University of Alberta, writes:

I’m Métis because I belong (and claim allegiance) to a set of Métis memories, territories, and leaders who challenged and continue to challenge colonial authorities’ unitary claims to land and society. What’s your excuse for recognizing me – for recognizing us – in any terms other than those of the Métis nationhood produced in these struggles?

(2011)

What is the “Métis Nation”?

The Métis Nation comprises contemporary Métis Citizens who descend from the historic Métis Homeland. The Métis National Council has represented the Métis Nation on both the national and international stages since 1983. Métis Nation British Columbia, Métis Nation Alberta, Métis Nation Saskatchewan, Manitoba Métis Federation, and Métis Nation of Ontario are regional governing members of the national council.

Can anyone be a Métis Citizen?

No.

Self-identification is one of four criteria that each Métis Citizen must meet to register with the Nation. This concept of Métis identity is complicated by those who self-identify as Métis because of their longing to belong to one of the Constitutional Aboriginal groups in Section 35 (1) but cannot claim Indian Status or assert their Inuit ancestry. Many of these individuals believe their mixed ancestry justifies their claim to be Métis. As we have seen in the definition of who is Métis, there are individuals who are not in turn accepted by the Métis Nation because they have no connection to the historic Métis Homeland and no ancestral ties are not Métis.

What does “Métis Citizen” mean?

The Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Powley (2003) further defined the s. 35 term of Métis. The Powley Story[1]explains the importance of this case for Métis citizenry.

The Supreme Court further clarified the definition of Métis, stating:

“Métis” does not encompass all individuals with mixed Indian and European heritage; rather, it refers to distinctive peoples who, in addition to their mixed ancestry, developed their own customs, way of life, and recognizable group identity separate from their Indian or Inuit and European forebears. Métis communities evolved and flourished prior to the entrenchment of European control, when the influence of European settlers and political institutions became pre-eminent.

Following the Powley decision, Métis Nation British Columbia (MNBC) implemented the Métis Identification Registry[2] in 2005.

How many Métis are there?

In 2016, 587,545 people identified as Métis, representing 32.3% of the total Indigenous population and 1.4% of the total Canadian population.

Do Métis people pay taxes?

Métis Citizens are not exempt from paying Provincial Sales Tax (PST) or Goods and Services Tax (GST). Métis people in Canada contribute over a billion dollars in taxes each year.

Do Métis people get free post-secondary education?

Métis students are not eligible for funding through the federal government’s Post-Secondary Student Support program; only status First Nations and Inuit students are eligible for funding through that program. Métis students in BC can apply to MNBC for post-secondary funding through the MNBC Indigenous Skills and Employment Training program, which is funded by Employment and Social Development Canada. Other options for Métis students include student aid, scholarships and bursaries.

Métis culture

Métis culture is very different from First Nations and Inuit cultures. The red Voyageur sash is recognized as a part of the distinct Métis culture. It was part of the clothing worn by Métis people every day and had many uses such as a holder, washcloth, bridle or saddle blanket. The sash is worn by Métis people today in celebration of their culture and identity.

The Métis flag[3] has a blue background with a white infinity symbol and depicts the joining of two cultures and the existence of a people forever.

Métis traditional clothing styles are a mixture of European and First Nation styles. The main decorating method was the flower beadwork or embroidery that the Métis are famous for. The traditional dance of the Métis includes the waltz Quadrille, the square dance, Drops of Brandy, the Duck Dance, la Double Gigue, and the Red River Jig, which is the most widely known of the dances. The main musical instrument of the Métis is the fiddle, which the Métis traditionally made from maple wood and birch bark. Unlike other traditional styles of music, the Métis style of fiddle music is not contained in a bar structure, and this creates a bounce to the tune that is unique to the Métis.

The Métis were also known by many other names, including the “buffalo hunters.” During the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Métis were established as the foremost processors and suppliers of pemmican to the new world. The Métis Nation’s gross national product from this source was larger than the total revenues of other economies during that time.

Métis language

One of the factors that makes the Métis culture distinct is the creation of a language that is syncretic, meaning it is not classifiable as belonging to just one language family. Much like the double ancestry of the Métis, the Michif language has grammatical and lexical features of both Indigenous (Cree, Dene, and Ojibwa) and French (Indo-European language). Verbs, sounds, and nouns from the Saulteaux language have also been absorbed. This creates a language that is very unique among languages around the globe, as no other languages show mixed nouns from one language and verbs from another in the manner that Michif does.

Métis spirituality

A common misconception is that the Métis practised only the religion of their fathers (Catholic or Protestant). The reality is a spiritual mixture is as complex as Métis people. Métis children learned from both their father’s and mother’s religious background and traditional teachings. Métis learned to live with both worlds, with First Nations’ and Settler spiritual beliefs.

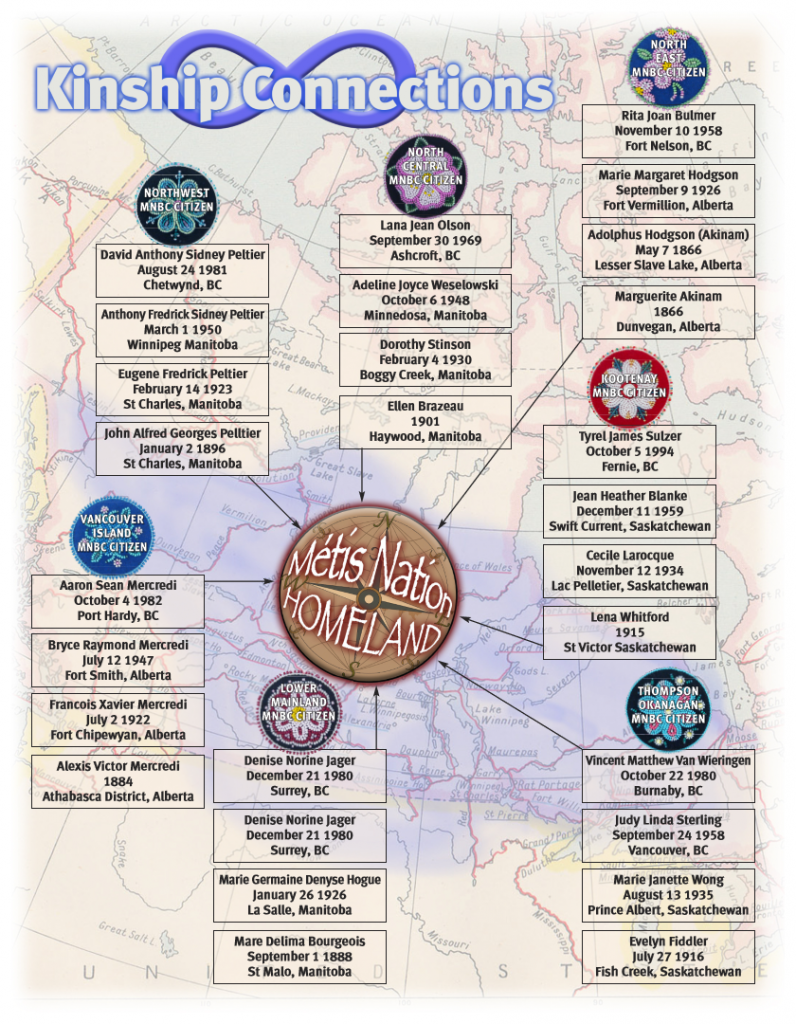

Kinship connections

Métis Nation British Columbia (MNBC) is a self-governing Nation. The governance structure includes seven geographic regions and 37 Métis chartered communities.

The Kinship Connections diagram represents seven MNBC Citizens, one from each region. Beginning in the North West (top left corner) with David Anthony Sidney Peltier, the diagram shows how each of the Métis Citizens is directly connected to the historic Métis Homeland through kinship connections.

All Métis Citizens in British Columbia have this same connection. They have an understanding of who they are through the well-documented experience of their ancestors that connect them to the historic Métis Homeland and the founders of the first Métis Nation who had settled in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Ontario.

Media Attributions

- Fig 1.3: Kinship Connections. Métis Nation British Columbia (MNBC), 2017 © MNBC. It is not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of MNBC.

a language historically spoken by Métis people, mixing words from French, Cree, and Dene.