Module 1: Ethical and Legal Considerations

Métis Governance Practices

Principles of ethical Métis research

Here, we discuss Métis-specific culturally competent ethical research principles that are adhered to by the Métis Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization in its research. These principles are not rigid rules, but a starting point for ethical research with Métis communities.

The National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) identifies six principles of ethical Métis research:

- Reciprocal Relationships

- “Respect for”

- Safe and Inclusive Environments

- Recognize Diversity

- “Research Should”

- Métis Context

Learner notes

The following Métis-specific culturally competent ethical research principles are adhered to by the Métis Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization in its research, who note for outside groups who choose to use or adapt them that, “The principles are not intended to be enforceable rules that must be followed but rather are a well thought out starting point to engage Métis communities in ethical research.” (Métis Centre of NAHO, 2018)

They are not trademarked like the OCAP®.

Source and recommended reading: National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) (2018). Principles of Ethical Métis Research [PDF]. Quotes in the below section come from this document.

Also see Indigenous Data Sovereignty | Research at UCalgary | University of Calgary

Reciprocal Relationships

Researchers should build equal partnerships with the Métis community, engage with community members, and ensure that responsibilities and benefits are shared.

“Building these relationships involves three parts: engaging the community by going among the people and becoming known, earning acceptance through this process, and then getting community involvement once the trusting relationship is established.”

—Cited from Principles of Ethical Métis Research [PDF] | Métis Centre at NAHO (achh.ca)

“Respect for”

Respect should be shown for individual and collective perspectives, community practices and protocols, confidentiality, autonomy, identity, and gender diversity.

“[R]espect is for ‘both’ the individual and the collective. This is one thing that makes doing research in Métis communities unique and is consistent with the view that Métis live with a foot in two worlds, an Aboriginal one and a Western one. For example, given a particular situation, a Métis community may choose to want individual consent, collective consent, or both.”

Safe and Inclusive Environments

Research must be inclusive of various age groups, genders, sexual identities, and diverse concepts of Indigeneity, and should maintain inclusivity throughout the research process.

“By this it is meant that research should, when appropriate, be inclusive to youth and elders, all genders and sexual identities, find the correct balance of individual and collective influence, and be inclusive of a variety of concepts of [Indigeneity].”

Diversity

Researchers should recognize and account for the diversity within Métis communities, including differences in beliefs, values, worldviews, and geographic locations.

“There can be a great diversity even within a single Métis community. Individuals within this community may, for example, have beliefs that are anywhere along a belief system continuum from very contemporary to very traditional and they may live their lives according to this system of belief.”

Learner notes

The use of the terms “Métis” and “métis” is complex and contentious. When capitalized, the term often describes people of the Métis Nation who trace their origins to the Red River Valley and the prairies beyond. The Métis National Council (MNC), the political organization that represents the Métis Nation, defined “Métis” in 2002 as “a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal Peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.” The MNC defines the Métis homeland as the three Prairie provinces and parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northern United States. Members of the Métis Nation have a common culture, ancestral language (Michif), history and political tradition, and are connected through an extensive network of kin relations.

Sources and recommended readings: Indigenous Data Sovereignty | Research at UCalgary | University of Calgary and Principles of Ethical Métis Research [PDF] | Métis Centre at NAHO (achh.ca)

“Research Should”

Ethical research should have outcomes that are relevant to the Métis community, accurate, beneficial to all involved, responsible, and should acknowledge the contributions of participants and community partners.

“Research should protect Métis cultural knowledge.”

Métis Context

Researchers should have a deep understanding of Métis history, values, knowledge, and context. They should also involve Métis experts and navigate the complexities of Métis worldviews and straddling of cultural perspectives.

“Knowing history and the Métis context can also help researchers navigate the political and geographic complexities that may arise.”

Additional Métis governance practices in Canada: OCAS

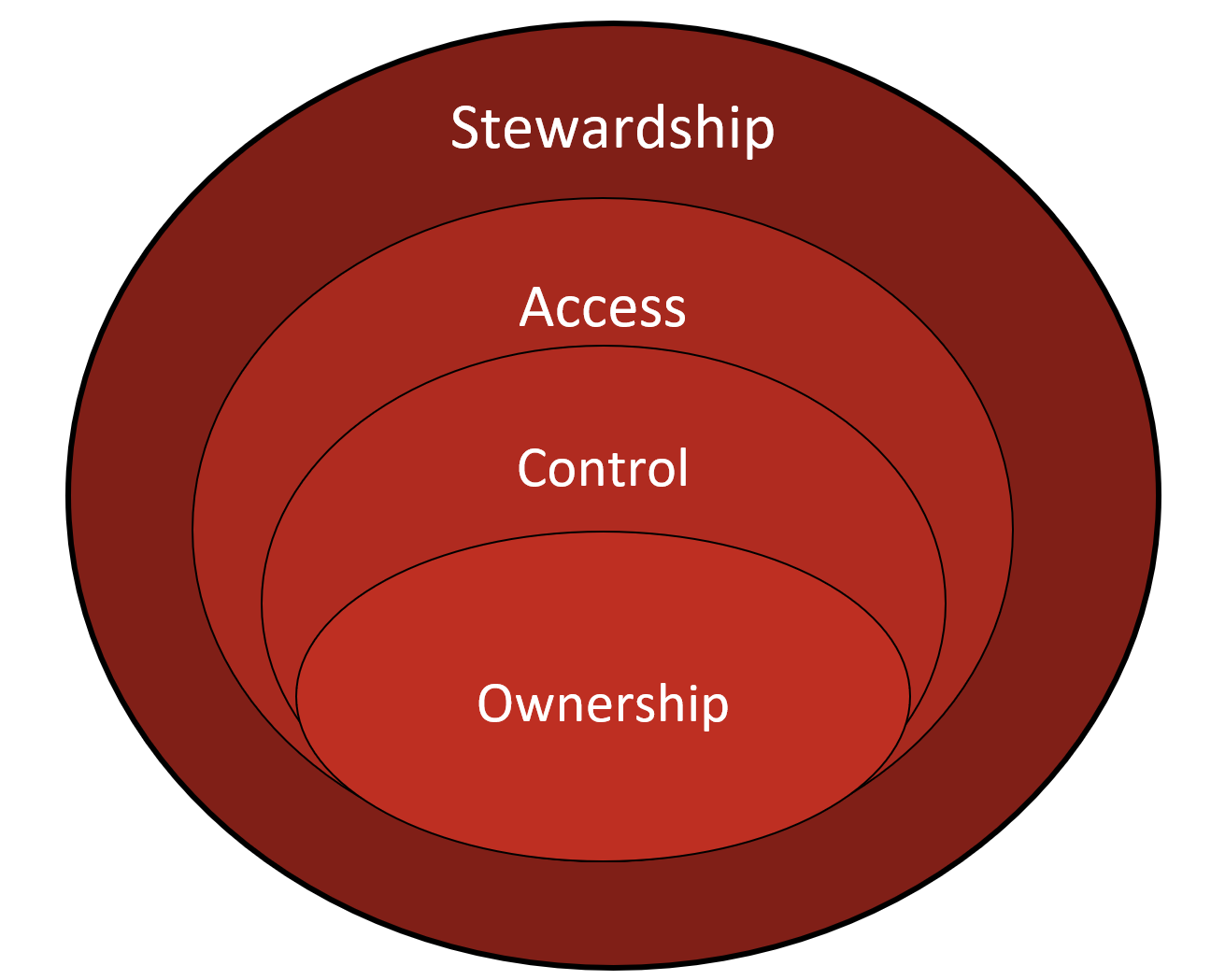

The following principles of OCAS (ownership, control, access and stewardship) were developed by Métis communities and are essential for ensuring the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Many Métis communities across Canada follow the ethical guidelines of OCAS.

Learner notes

Note that the Métis OCAS and the First Nations OCAP® are similar, but the “S” in OCAS stands for “stewardship” where the “P” in OCAP® stands for “possession.”

Source and recommended reading: Indigenous Data Sovereignty – Research Data Services – LibGuides at University of Victoria Libraries (uvic.ca)

O is for Ownership

Ownership recognizes that Indigenous communities have inherent rights to their data, culture, and resources. It emphasizes that data and information belong to the community alone.

C is for Control

Control empowers Indigenous communities to make decisions about their data, including who can access it, how it is used, and under what conditions. Control ensures that community members have a say in data governance.

A is for Access

Access ensures that community members have access to relevant data and information. It emphasizes transparency and openness while respecting cultural protocols and privacy.

S is for Stewardship

Stewardship acknowledges the responsibility of safeguarding data and resources for future generations. Stewardship involves ethical management, protection, and preservation.

Learner notes

Attributions

- “Visual of OCAS” diagram by Connie Strayer and Robyn Grebliunas is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.