Chapter 2. Introduction to Major Perspectives

2.2 Psychodynamic Psychology

Jennifer Walinga

Learning Objectives

- Understand some of the psychological forces underlying human behaviour.

- Identify levels of consciousness.

- Critically discuss various models and theories of psychodynamic and behavioural psychology.

- Understand the concept of psychological types and identify applications and examples in daily life.

Sigmund Freud

The psychodynamic perspective in psychology proposes that there are psychological forces underlying human behaviour, feelings, and emotions. Psychodynamics originated with Sigmund Freud (Figure 2.5) in the late 19th century, who suggested that psychological processes are flows of psychological energy (libido) in a complex brain. In response to the more reductionist approach of biological, structural, and functional psychology movements, the psychodynamic perspective marks a pendulum swing back toward more holistic, systemic, and abstract concepts and their influence on the more concrete behaviours and actions. Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis assumes that much of mental life is unconscious, and that past experiences, especially in early childhood, shape how a person feels and behaves throughout life.

Consciousness is the awareness of the self in space and time. It can be defined as human awareness of both internal and external stimuli. Researchers study states of human consciousness and differences in perception in order to understand how the body works to produce conscious awareness. Consciousness varies in both arousal and content, and there are two types of conscious experience: phenomenal, or in the moment, and access, which recalls experiences from memory.

First appearing in the historical records of the ancient Mayan and Incan civilizations, various theories of multiple levels of consciousness have pervaded spiritual, psychological, medical, and moral speculations in both Eastern and Western cultures. The ancient Mayans were among the first to propose an organized sense of each level of consciousness, its purpose, and its temporal connection to humankind. Because consciousness incorporates stimuli from the environment as well as internal stimuli, the Mayans believed it to be the most basic form of existence, capable of evolution. The Incas, however, considered consciousness to be a progression, not only of awareness but of concern for others as well.

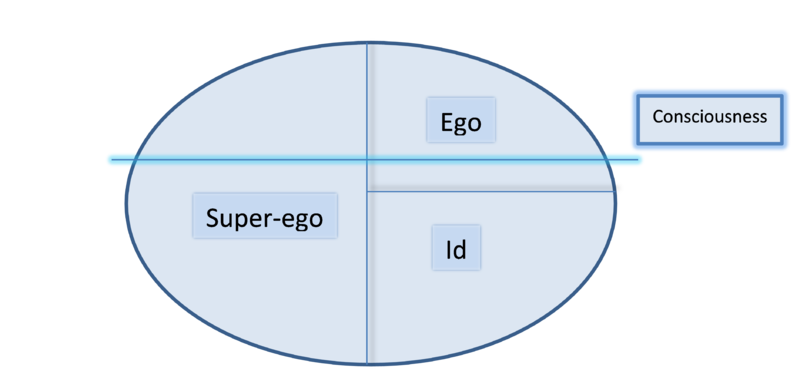

Sigmund Freud divided human consciousness into three levels of awareness: the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. Each of these levels corresponds to and overlaps with Freud’s ideas of the id, ego, and superego. The conscious level consists of all those things we are aware of, including things that we know about ourselves and our surroundings. The preconscious consists of those things we could pay conscious attention to if we so desired, and where many memories are stored for easy retrieval. Freud saw the preconscious as those thoughts that are unconscious at the particular moment in question, but that are not repressed and are therefore available for recall and easily capable of becoming conscious (e.g., the “tip of the tongue” effect). The unconscious consists of those things that are outside of conscious awareness, including many memories, thoughts, and urges of which we are not aware. Much of what is stored in the unconscious is thought to be unpleasant or conflicting; for example, sexual impulses that are deemed “unacceptable.” While these elements are stored out of our awareness, they are nevertheless thought to influence our behaviour.

Figure 2.6 illustrates the respective levels of id, ego, and superego. In this diagram, the bright blue line represents the divide between consciousness (above) and unconsciousness (below). Below this line, but above the id, is the preconscious level. The lowest segment is the unconscious. Like the ego, the superego has conscious and unconscious elements, while the id is completely unconscious. When all three parts of the personality are in dynamic equilibrium, the individual is thought to be mentally healthy. However if the ego is unable to mediate between the id and the superego, an imbalance occurs in the form of psychological distress.

While Freud’s theory remains one of the best known, various schools within the field of psychology have developed their own perspectives. For example:

- Developmental psychologists view consciousness not as a single entity, but as a developmental process with potential higher stages of cognitive, moral, and spiritual quality.

- Social psychologists view consciousness as a product of cultural influence having little to do with the individual.

- Neuropsychologists view consciousness as ingrained in neural systems and organic brain structures.

- Cognitive psychologists base their understanding of consciousness on computer science.

Most psychodynamic approaches use talk therapy, or psychoanalysis, to examine maladaptive functions that developed early in life and are, at least in part, unconscious. Psychoanalysis is a type of analysis that involves attempting to affect behavioural change through having patients talk about their difficulties. Practising psychoanalysts today collect their data in much the same way as Freud did, through case studies, but often without the couch. The analyst listens and observes, gathering information about the patient. Psychoanalytic scientists today also collect data in formal laboratory experiments, studying groups of people in more restricted, controlled ways (Cramer, 2000; Westen, 1998).

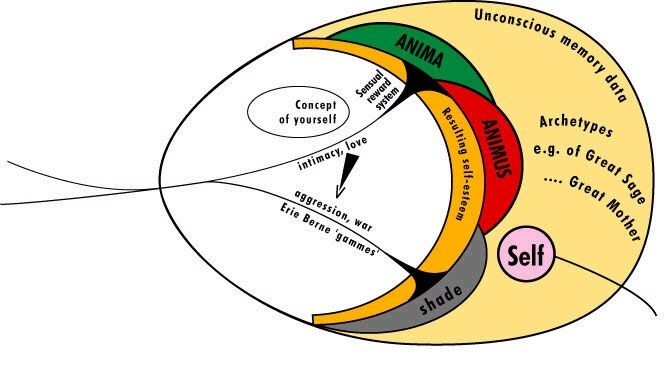

Carl Jung

Carl Jung (1875-1961) expanded on Freud’s theories, introducing the concepts of the archetype, the collective unconscious, and individuation — or the psychological process of integrating the opposites, including the conscious with the unconscious, while still maintaining their relative autonomy (Figure 2.7). Jung focused less on infantile development and conflict between the id and superego, and more on integration between different parts of the person.

The following are Jung’s concepts that are still prevalent today:

Active imagination: This refers to activating our imaginal processes in waking life in order to tap into the unconscious meanings of our symbols.

Archetypes: These primordial images reflect basic patterns or universal themes common to us all and that are present in the unconscious. These symbolic images exist outside space and time. Examples are the shadow, animus, anima, the old wise person, and the innocent child. There are also nature archetypes, like fire, ocean, river, mountain.

- Anima is the archetype symbolizing the unconscious female component of the male psyche. Tendencies or qualities often thought of as feminine.

- Animus is the archetype symbolizing the unconscious male component of the female psyche. Tendencies or qualities often thought of as masculine.

- Self is the archetype symbolizing the totality of the personality. It represents the striving for unity, wholeness, and integration.

- Persona is the mask or image a person presents to the world. It is designed to make a particular impression on others, while concealing a person’s true nature.

- Shadow is the side of a personality that a person does not consciously display in public. It may have positive or negative qualities.

- Dreams are specific expressions of the unconscious that have a definite, purposeful structure indicating an underlying idea or intention. The general function of dreams is to restore a person’s total psychic equilibrium.

- Complexes are usually unconscious and repressed emotionally toned symbolic material that is incompatible with consciousness. Complexes can cause constant psychological disturbances and symptoms of neurosis. With intervention, they can become conscious and greatly reduced in their impact.

Individuation: Jung believed that a human being is inwardly whole, but that most people have lost touch with important parts of themselves. Through listening to the messages of our dreams and waking imagination, we can contact and reintegrate our different parts. The goal of life is individuation, which is the process of integrating the conscious with the unconscious, synergizing the many components of the psyche. Jung asserted: “Trust that which gives you meaning and accept it as your guide” (Jung, 1951, p. 3). Each human being has a specific nature and calling uniquely his or her own, and unless these are fulfilled through a union of conscious and unconscious, the person can become sick. Today, the term “individuation” is used in the media industry to describe new printing and online technologies that permit “mass customization” of media (newspaper, online, television) so that its contents match each individual user’s unique interests, shifting from the mass media practice of producing the same contents for all readers, viewers, listeners, or online users (Chen, Wang, & Tseng, 2009). Marshall McLuhan, the communications theorist, alluded to this trend in customization when discussing the future of printed books in an electronically interconnected world (McLuhan & Nevitt, 1972).

Mandala: For Jung, the mandala (which is the Sanskrit word for “circle”) was a symbol of wholeness, completeness, and perfection, and symbolized the self.

Mystery: For Jung, life was a great mystery, and he believed that humans know and understand very little of it. He never hesitated to say, “I don’t know,” and he always admitted when he came to the end of his understanding.

Neurosis: Jung had a hunch that what passed for normality often was the very force that shattered the personality of the patient. He proposed that trying to be “normal” violates a person’s inner nature and is itself a form of pathology. In the psychiatric hospital, he wondered why psychiatrists were not interested in what their patients had to say.

Story: Jung concluded that every person has a story, and when derangement occurs, it is because the personal story has been denied or rejected. Healing and integration come when the person discovers or rediscovers his or her own personal story.

Symbol: A symbol is a name, term, or picture that is familiar in daily life, but for Jung it had other connotations besides its conventional and obvious meaning. To Jung, a symbol implied something vague and partially unknown or hidden, and was never precisely defined. Dream symbols carried messages from the unconscious to the rational mind.

Unconscious: This basic tenet, as expressed by Jung, states that all products of the unconscious are symbolic and can be taken as guiding messages. Within this concept, there are two types:

- Personal unconscious: This aspect of the psyche does not usually enter an individual’s awareness, but, instead, appears in overt behaviour or in dreams.

- Collective unconscious: This aspect of the unconscious manifests in universal themes that run through all human life. The idea of the collective unconscious assumes that the history of the human race, back to the most primitive times, lives on in all people.

Word association test: This is a research technique that Jung used to explore the complexes in the personal unconscious. It consisted of reading 100 words to someone, one at a time, and having the person respond quickly with a word of his or her own.

Psychological Types

According to Jung, people differ in certain basic ways, even though the instincts that drive us are the same. Jung distinguished two general attitudes–introversion and extraversion–and four functions–thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuiting:

- Introvert: Inner-directed; needs privacy and space; chooses solitude to recover energy; often reflective.

- Extravert: Outer-directed; needs sociability; chooses people as a source of energy; often action-oriented.

- Thinking function: Logical; sees cause and effect relations; cool, distant, frank, and questioning.

- Feeling function: Creative, warm, intimate; has a sense of valuing positively or negatively. (Note that this is not the same as emotion.)

- Sensing function: Sensory; oriented toward the body and senses; detailed, concrete, and present.

- Intuitive: Sees many possibilities in situations; goes with hunches; impatient with earthy details; impractical; sometimes not present

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment is a psychometric questionnaire designed to measure psychological preferences in how people perceive the world and make decisions. The original developers of the Myers-Briggs personality inventory were Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs-Myers (1980, 1995). Having studied the work of Jung, the mother-daughter team turned their interest in human behaviour into a practical application of the theory of psychological types. They began creating the indicator during World War II, believing that a knowledge of personality preferences would help women who were entering the industrial workforce for the first time to identify the sort of wartime jobs that would be “most comfortable and effective.”

The initial questionnaire became the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), first published in 1962 and emphasizing the value of naturally occurring differences (CAPT, 2012). These preferences were extrapolated from the typological theories proposed by Jung and first published in his 1921 book Psychological Types (Adler & Hull, 2014). Jung theorized that there are four principal psychological functions by which we experience the world: sensation, intuition, feeling, and thinking, with one of these four functions being dominant most of the time. The MBTI provides individuals with a measure of their dominant preferences based on the Jungian functions.

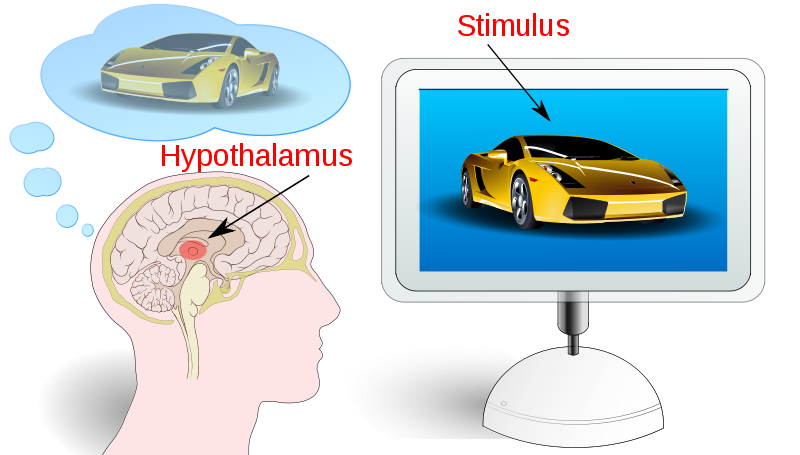

Research Focus: The Theory of Buyer Behaviour

Jungian theory influenced a whole realm of social psychology called Consumer Behaviour (Howard & Sheth, 1968). Consumer behaviour is the study of individuals, groups, or organizations and the processes they use to select, secure, and dispose of products, services, experiences, or ideas to satisfy needs, and the impacts that these processes have on the consumer and society. Blending psychology, sociology, social anthropology, marketing, and economics, the study of consumer behaviour attempts to understand the decision-making processes of buyers, such as how emotions affect buying behaviour (Figure 2.8); it also studies characteristics of individual consumers, such as demographics, and behavioural variables and external influences, such as family, education, and culture, in an attempt to understand people’s desires.

The black box model (Sandhusen, 2000) captures this interaction of stimuli, consumer characteristics, decision processes, and consumer responses. Stimuli can be experienced as interpersonal stimuli (between people) or intrapersonal stimuli (within people). The black box model is related to the black box theory of behaviourism, where the focus is set not on the processes inside a consumer, but on the relation between the stimuli and the response of the consumer. The marketing stimuli are planned and processed by the companies, whereas the environmental stimuli are based on social, economic, political, and cultural circumstances of a society. The buyer’s black box contains the buyer characteristics and the decision process, which determines the buyer’s response (Table 2.1).

| [Skip Table] | ||||

| Environmental Factors | Buyer’s Black Box | Buyer’s Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing Stimuli | Environmental Stimuli | Buyer Characteristics | Design Process | |

|

|

|

|

|

Dreaming and Psychodynamic Psychology

Freud showed a great interest in the interpretation of human dreams, and his theory centred on the notion of repressed longing — the idea that dreaming allows us to sort through unresolved, repressed wishes. Freud’s theory described dreams as having both latent and manifest content. Latent content relates to deep unconscious wishes or fantasies, while manifest content is superficial and meaningless. Manifest content often masks or obscures latent content.

Theories emerging from the work of Freud include the following:

Threat-simulation theory suggests that dreaming should be seen as an ancient biological defence mechanism. Dreams are thought to provide an evolutionary advantage because of their capacity to repeatedly simulate potential threatening events. This process enhances the neurocognitive mechanisms required for efficient threat perception and avoidance. During much of human evolution, physical and interpersonal threats were serious enough to reward reproductive advantage to those who survived them. Therefore, dreaming evolved to replicate these threats and continually practice dealing with them. This theory suggests that dreams serve the purpose of allowing for the rehearsal of threatening scenarios in order to better prepare an individual for real-life threats.

Expectation fulfillment theory posits that dreaming serves to discharge emotional arousals (however minor) that haven’t been expressed during the day. This practice frees up space in the brain to deal with the emotional arousals of the next day and allows instinctive urges to stay intact. In effect, the expectation is fulfilled (i.e., the action is completed) in the dream, but only in a metaphorical form so that a false memory is not created. This theory explains why dreams are usually forgotten immediately afterwards.

Other neurobiological theories also exist:

Activation-synthesis theory: One prominent neurobiological theory of dreaming is the activation-synthesis theory, which states that dreams don’t actually mean anything. They are merely electrical brain impulses that pull random thoughts and imagery from our memories. The theory posits that humans construct dream stories after they wake up, in a natural attempt to make sense of the nonsensical. However, given the vast documentation of realistic aspects to human dreaming as well as indirect experimental evidence that other mammals (e.g., cats) also dream, evolutionary psychologists have theorized that dreaming does indeed serve a purpose.

Continual-activation theory: The continual-activation theory of dreaming proposes that dreaming is a result of brain activation and synthesis. Dreaming and REM sleep are simultaneously controlled by different brain mechanisms. The hypothesis states that the function of sleep is to process, encode, and transfer data from short-term memory to long-term memory through a process called “consolidation.” However, there is not much evidence to back up consolidation as a theory. NREM (non-rapid eye movement or non-REM) sleep processes the conscious-related memory (declarative memory), and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep processes the unconscious-related memory (procedural memory).

The underlying assumption of continual-activation theory is that during REM sleep, the unconscious part of a brain is busy processing procedural memory. Meanwhile, the level of activation in the conscious part of the brain descends to a very low level as the inputs from the senses are basically disconnected. This triggers the “continual-activation” mechanism to generate a data stream from the memory stores to flow through to the conscious part of the brain.

Nielsen and colleagues (2003) investigated the dimensional structure of dreams by administering the Typical Dreams Questionnaire (TDQ) to 1,181 first-year university students in three Canadian cities. A profile of themes was found that varied little by age, gender, or region; however, differences that were identified correlated with developmental milestones, personality attributes, or sociocultural factors. Factor analysis found that women’s dreams related mostly to negative factors (failure, loss of control, snakes/insects), while men’s dreams related primarily to positive factors (magic/myth, alien life).

Research Focus: Can Dreaming Enhance Problem Solving?

Stemming from Freudian and Jungian theories of dream states, researchers in Lancaster, UK (Sio & Ormerod, 2009; Sio Monaghan, & Ormerod, 2013) and in Alberta, Canada (Both, Needham, & Wood, 2004) explored the role of “incubation” in facilitating problem solving. Incubation is the concept of “sleeping on a problem,” or disengaging from actively and consciously trying to solve a problem, in order to allow, as the theory goes, the unconscious processes to work on the problem. Incubation can take a variety of forms, such as taking a break, sleeping, or working on another kind of problem either more difficult or less challenging. Findings suggest that incubation can, indeed, have a positive impact on problem-solving outcomes. Interestingly, lower-level cognitive tasks (e.g., simple math or language tasks, vacuuming, putting items away) resulted in higher problem-solving outcomes than more challenging tasks (e.g., crossword puzzles, math problems). Educators have also found that taking active breaks increases children’s creativity and problem-solving abilities in classroom settings.

There are several hypotheses that aim to explain the conscious-unconscious effects on problem solving:

- Spreading activation: When problem solvers disengage from the problem-solving task, they naturally expose themselves to more information that can serve to inform the problem-solving process. Solvers are sensitized to certain information and can benefit from conceptual combination of disparate ideas related to the problem.

- Selective forgetting: Once disengaged from the problem-solving process, solvers are freer to let go of certain ideas or concepts that may be inhibiting the problem-solving process, allowing a cleaner, fresher view of the problem and revealing clearer pathways to solution.

- Problem restructuring: When problem solvers let go of the initial problem, they are then freed to restructure or reorganize their representation of the problem and thereby capitalize on relevant information not previously noticed, switch strategies, or rearrange problem information in a manner more conducive to solution pathways.

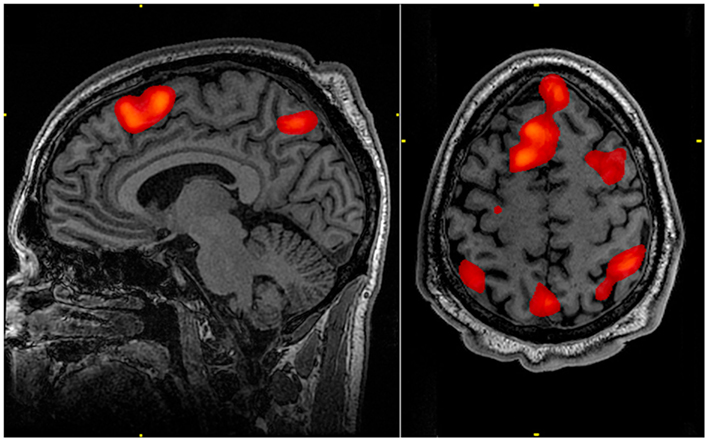

The study of neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) seeks to link activity within the brain to subjective human experiences in the physical world. Progress in neurophilosophy has come from focusing on the body rather than the mind (Squire, 2008). In this context, the neuronal correlates of consciousness may be viewed as its causes, and consciousness may be thought of as a state-dependent property of some undefined complex, adaptive, and highly interconnected biological system. The NCC constitute the smallest set of neural events and structures sufficient for a given conscious percept or explicit memory (Figure 2.9).

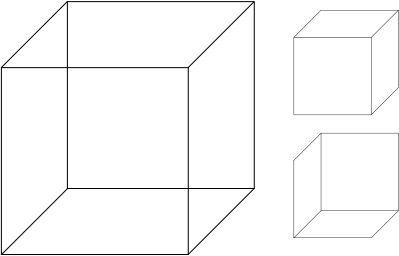

In the investigation into the NCC, our capacity to manipulate visual percepts in time and space has made vision a focus of study. Psychologists have perfected a number of techniques in which the seemingly simple relationship between a physical stimulus in the world and its associated principle in the subject’s mind is disturbed and therefore open for understanding. In this manner the neural mechanisms can be isolated, permitting visual consciousness to be tracked in the brain. In a perceptual illusion, the physical stimulus remains fixed while the perception fluctuates. The best known example is the Necker Cube (Koch, 2004): the 12 lines in the cube can be perceived in one of two different ways in depth (Figure 2.10).

A number of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiments have identified the activity underlying visual consciousness in humans and demonstrated quite conclusively that activity in various areas of the brain follows the mental perception and not the retinal stimulus (Rees & Frith, 2007), making it possible to link brain activity with perception (Figure 2.11).

Key Takeaways

- Psychodynamic psychology emphasizes the systematic study of the psychological forces that underlie human behaviour, feelings, and emotions and how they might relate to early experience.

- Consciousness is the awareness of the self in space and time and is defined as human awareness to both internal and external stimuli.

- Sigmund Freud divided human consciousness into three levels of awareness: the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. Each of these levels corresponds and overlaps with his ideas of the id, ego, and superego.

- Most psychodynamic approaches use talk therapy to examine maladaptive functions that developed early in life and are, at least in part, unconscious.

- Carl Jung expanded upon Freud’s theories, introducing the concepts of the archetype, the collective unconscious, and individuation.

- Freud’s theory describes dreams as having both latent and manifest content. Latent content relates to deep unconscious wishes or fantasies while manifest content is superficial and meaningless.

- Unconscious processing includes several theories: threat simulation theory, expectation fulfillment theory, activation synthesis theory, continual activation theory.

- One application of unconscious processing includes incubation as it relates to problem solving: the concept of “sleeping on a problem” or disengaging from actively and consciously trying to solve a problem in order to allow one’s unconscious processes to work on the problem.

- The study of neural correlates of consciousness seeks to link activity within the brain to subjective human experiences in the physical world.

- In a perceptual illusion, like the Necker Cube, the physical stimulus remains fixed while the perception fluctuates, allowing the neural mechanisms to be isolated and permitting visual consciousness to be tracked in the brain.

- Activity in the brain can be studied and captured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Utilize the principles of the psychodynamic school of thought to reflect on a recent dream you experienced. What might the dream imply or represent? Try to trace one of your qualities or characteristics to a prior experience or learning.

- Jung has influenced a variety of practices in psychology today including therapeutic and organizational. Can you identify other areas of society where “archetypes” may play a role?

- Debate with your group the value or danger of “mass customization.” What issues or controversies does the concept of customized marketing and product development pose?

Image Attributions

Figure 2.5: Freud Jung in front of Clark Hall (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b5/Hall_Freud_Jung_in_front_of_Clark.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 2.6: Visual representation of Freud’s id, ego and superego and the level of consciousness (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Id_ego_superego.png) used under CC BY SA 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en).

Figure 2.7: Graphical model of Carl Jung’s theory – English version by Andrzej Brodziak (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scheme-Jung.jpg) used under CC-BY-SA 2.5 Generic license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en).

Figure 2.8: Neuromarketing schema by Benoit Rochon (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neuromarketing_fr.svg) used under CC BY 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en).

Figure 2.9: Neural Correlates Of Consciousness by Christof Koch (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neural_Correlates_Of_Consciousness.jpg) used under CC BY SA 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en).

Figure 2.10: Necker’s cube, a type of optical illusion by Stevo-88 (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Necker%27s_cube.svg) is in the public domain.

Figure 2.11: FMRI scan during working memory tasks by John Graner (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FMRI_scan_during_working_memory_tasks.jpg) is in the public domain.

References

Adler, G., & Hull, R. F.C. (2014). Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 6: Psychological Types. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Both, L., Needham, D., & Wood, E. (2004). Examining Tasks that Facilitate the Experience of Incubation While Problem-Solving. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 50(1), 57–67.

Briggs-Myers, Isabel, & Myers, Peter B. (1980, 1995). Gifts differing: Understanding personality type. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black Publishing.

CAPT (Center for Applications of Psychological Type. (2012). The story of Isabel Briggs Myers. Retrieved from http://www.capt.org/mbti-assessment/isabel-myers.htm

Chen, Songlin, Wang, Yue, & Tseng, Mitchell (2009). Mass Customization as a Collaborative Engineering Effort. International Journal of Collaborative Engineering, 1(2), 152–167.

Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today. American Psychologist, 55, 637–646.

Howard, J., & Sheth, J.N. (1968). Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons.

Jung, C. G. (1951). Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self (Collected Works Vol. 9 Part 2). Princeton, N.J.: Bollingen.

Koch, Christof (2004). The quest for consciousness: a neurobiological approach. Englewood, US-CO: Roberts & Company Publishers.

McLuhan, Marshall, & Nevitt, Barrington. (1972). Take today: The executive as dropout. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace.

Nielsen, Tore A., Zadra, Antonio L., Simard, Valérie Saucier, Sébastien Stenstrom, Philippe Smith, Carlyle, & Kuiken, Don (2003). The typical dreams of Canadian university students dreaming. Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams, 13(4), 211–235.

Rees G., & Frith C. (2007). Methodologies for identifying the neural correlates of consciousness. In: The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Velmans, M. & Schneider, S., (Eds.), pp. 553–66. Blackwell: Oxford, UK.

Sandhusen, R. (2000). Marketing. New York, NY: Barron’s Educational Series.

Sio, U.N., & Ormerod, T.C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin,135(1), 94–120.

Sio U.N., Monaghan P., & Ormerod T. (2013). Sleep on it, but only if it is difficult: Effects of sleep on problem solving. Memory and Cognition, 41(2), 159–66.

Squire, Larry R. (2008). Fundamental neuroscience (3rd ed.). Waltham, Mass: Academic Press. p. 1256.

Westen, D. (1998). The scientific legacy of Sigmund Freud: Toward a psychodynamically informed psychological science. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 333–371.

- Adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consumer_behaviour by J. Walinga. ↵