Main Body

Chapter 4. Society and Social Interaction

Learning Objectives

- Describe the difference between preindustrial, industrial, and postindustrial societies

- Understand the role of environment on preindustrial societies

- Understand how technology impacts societal development

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

- Describe Durkheim’s functionalist view of modern society

- Understand the critical sociology view of modern society

- Explain the difference between Marx’s concept of alienation and Weber’s concept of rationalization

- Identify how feminists analyze the development of society

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

- Understand the sociological concept of reality as a social construct

- Define roles and describe their place in people’s daily interactions

- Explain how individuals present themselves and perceive themselves in a social context

Introduction to Society and Social Interaction

Early in the morning, a group of male warriors creeps out of the village and heads for the savannah. They must be careful not to wake the other members of the tribe, lest they be accosted by the women or elders. Once they have regrouped on the plains, the warriors begin preparing for the hunt. The eldest members of the group choose the most qualified hunters, known as ilmeluaya, meaning men who are not afraid of death. Warriors who are not selected are sent home in shame.

Once the select group has been chosen, the warriors begin the hunt. They scour the plains for footprints or droppings, and search for dense bushes or tall termite mounds that might conceal their resting prey. The search can take ten minutes to ten hours, but once a lion is found, the warriors quickly move into place.

Selected hunters ring bells and rattle the brush, forcing the lion away from its protected hiding spot. The goal is to face the beast one-on-one on the open savannah. There will be no tricks or cheating, simply warrior against warrior. If all goes as planned, the lion will be brought down with a single spear.

When the warriors return to the village with their trophy, it is the beginning of a weeklong celebration. Although the hunt must be planned in secret, news of the warriors’ success spreads quickly, and all village members come to congratulate the victors. The warrior who wounded the lion first is honoured and given a nickname based on his accomplishment. Songs are sung about the warrior, and from then on he will be remembered and acknowledged throughout the community, even among other tribes.

To the Maasai, lion hunting is about more than food and security. It is a way to strengthen the bonds of community and the hierarchy among the hunters. Disputes over power are settled before the hunt, and roles are reinforced at the end, with the bravest warrior receiving the lion’s tail as a trophy (Maasai Association 2011). Although Maasai society is very different from contemporary Canada, both can be seen as different ways of expressing the human need to cooperate and live together in order to survive.

4.1. Types of Societies

Maasai villagers, Iranians, Canadians—each is a society. But what does this mean? Exactly what is a society? In sociological terms, society refers to a group of people who live in a definable territory and share the same culture. On a broader scale, society consists of the people and institutions around us, our shared beliefs, and our cultural ideas.

Sociologist Gerhard Lenski (1924–) defined societies in terms of their technological sophistication. As a society advances, so does its use of technology. Societies with rudimentary technology are at the mercy of the fluctuations of their environment, while industrialized societies have more control over the impact of their surroundings and thus develop different cultural features. This distinction is so important that sociologists generally classify societies along a spectrum of their level of industrialization, from preindustrial to industrial to postindustrial.

Preindustrial Societies

Before the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of machines, societies were small, rural, and dependent largely on local resources. Economic production was limited to the amount of labour a human being could provide, and there were few specialized occupations. The very first occupation was that of hunter-gatherer.

Hunter-Gatherer

Hunter-gatherer societies demonstrate the strongest dependence on the environment of the various types of preindustrial societies. As the basic structure of all human society until about 10,000–12,000 years ago, these groups were based around kinship or tribes. Hunter-gatherers relied on their surroundings for survival—they hunted wild animals and foraged for uncultivated plants for food. When resources became scarce, the group moved to a new area to find sustenance, meaning they were nomadic. These societies were common until several hundred years ago, but today only a few hundred remain in existence, such as indigenous Australian tribes sometimes referred to as “aborigines,” or the Bambuti, a group of pygmy hunter-gatherers residing in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Hunter-gatherer groups are quickly disappearing as the world’s population explodes.

Pastoral

Changing conditions and adaptations led some societies to rely on the domestication of animals where circumstances permitted. Roughly 7,500 years ago, human societies began to recognize their ability to tame and breed animals and to grow and cultivate their own plants. Pastoral societies rely on the domestication of animals as a resource for survival. Unlike earlier hunter-gatherers who depended entirely on existing resources to stay alive, pastoral groups were able to breed livestock for food, clothing, and transportation, creating a surplus of goods. Herding, or pastoral, societies remained nomadic because they were forced to follow their animals to fresh feeding grounds. Around the time that pastoral societies emerged, specialized occupations began to develop, and societies commenced trading with local groups.

Making Connections: The Big Picture

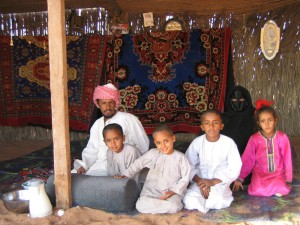

The Bedouin

Throughout Northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula live the Bedouin, modern-day nomads. While many different tribes of Bedouin exist, they all share similarities. Members migrate from one area to another, usually in conjunction with the seasons, settling near oases in the hot summer months. They tend to herds of goats, camels, and sheep, and they harvest dates in the fall (Kjeilen N.d.).

In recent years, there has been increased conflict between the Bedouin society and more modernized societies. National borders are harder to cross now than in the past, making the traditional nomadic lifestyle of the Bedouin difficult. The clash of traditions among Bedouin and other residents has led to discrimination and abuse. Bedouin communities frequently have high poverty and unemployment rates, and their members have little formal education (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 2005).

The future of the Bedouin is uncertain. Government restrictions on farming and residence are slowly forcing them to integrate into modern society. Although their ancestors have traversed the deserts for thousands of years, the days of the nomadic Bedouin may be at an end.

Horticultural

Around the same time that pastoral societies were on the rise, another type of society developed, based on the newly developed capacity for people to grow and cultivate plants. Previously, the depletion of a region’s crops or water supply forced pastoral societies to relocate in search of food sources for their livestock. Horticultural societies formed in areas where rainfall and other conditions allowed them to grow stable crops. They were similar to hunter-gatherers in that they largely depended on the environment for survival, but since they did not have to abandon their location to follow resources, they were able to start permanent settlements. This created more stability and more material goods and became the basis for the first revolution in human survival.

Agricultural

While pastoral and horticultural societies used small, temporary tools such as digging sticks or hoes, agricultural societies relied on permanent tools for survival. Around 3000 BCE., an explosion of new technology known as the Agricultural Revolution made farming possible—and profitable. Farmers learned to rotate the types of crops grown on their fields and to reuse waste products such as fertilizer, leading to better harvests and bigger surpluses of food. New tools for digging and harvesting were made of metal, making them more effective and longer lasting. Human settlements grew into towns and cities, and particularly bountiful regions became centres of trade and commerce.

This is also the age in which people had the time and comfort to engage in more contemplative and thoughtful activities, such as music, poetry, and philosophy. This period became referred to as the “dawn of civilization” by some because of the development of leisure and arts. Craftspeople were able to support themselves through the production of creative, decorative, or thought-provoking aesthetic objects and writings.

As agricultural techniques made the production of surpluses possible, social classes and power structures emerged. Those with the power to appropriate the surpluses were able to dominate the society. Classes of nobility and religious elites developed. Difference in social standing between men and women appeared. Slavery was institutionalized. As cities expanded, ownership and protection of resources became a pressing concern and militaries became more prominent.

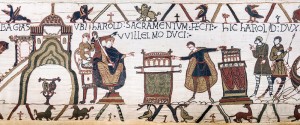

Feudal

In Europe, the ninth century gave rise to feudal societies. These societies contained a strict hierarchical system of power based around land ownership, protection, and mutual obligation. The nobility, known as lords, rewarded knights or vassals by granting them pieces of land. In return for the resources that the land provided, vassals promised to fight for their lords.

These individual pieces of land, known as fiefdoms, were cultivated by the lower class of serfs. In return for maintaining and working the land, serfs were guaranteed a place to live and protection from outside enemies. Power was handed down through family lines, with serf families serving lords for generations and generations. Ultimately, the social and economic system of feudalism was surpassed by the rise of capitalism and the technological advances of the industrial era.

Industrial Society

In the 18th century, Europe experienced a dramatic rise in technological invention, ushering in an era known as the Industrial Revolution. What made this period remarkable was the number of new inventions that influenced people’s daily lives. Within a generation, tasks that had until this point required months of labour became achievable in a matter of days. Before the Industrial Revolution, work was largely person- or animal-based, relying on human workers or horses to power mills and drive pumps. In 1782, James Watt and Matthew Boulton created a steam engine that could do the work of 12 horses by itself.

Steam power began appearing everywhere. Instead of paying artisans to painstakingly spin wool and weave it into cloth, people turned to textile mills that produced fabric quickly at a better price, and often with better quality. Rather than planting and harvesting fields by hand, farmers were able to purchase mechanical seeders and threshing machines that caused agricultural productivity to soar. Products such as paper and glass became available to the average person, and the quality and accessibility of education and health care soared. Gas lights allowed increased visibility in the dark, and towns and cities developed a nightlife.

One of the results of increased wealth, productivity, and technology was the rise of urban centres. Serfs and peasants, expelled from their ancestral lands, flocked to the cities in search of factory jobs, and the populations of cities became increasingly diverse. The new generation became less preoccupied with maintaining family land and traditions, and more focused on survival. Some were successful in acquiring wealth and achieving upward mobility for themselves and their family. Others lived in devastating poverty and squalor. Whereas the class system of feudalism had been rigid, and resources for all but the highest nobility and clergy scarce, under capitalism social mobility (both upward and downward) became possible.

It was during the 18th and 19th centuries of the Industrial Revolution that sociology was born. Life was changing quickly and the long-established traditions of the agricultural eras did not apply to life in the larger cities. Masses of people were moving to new environments and often found themselves faced with horrendous conditions of filth, overcrowding, and poverty. Social science emerged in response to the unprecedented scale of the social problems of modern society.

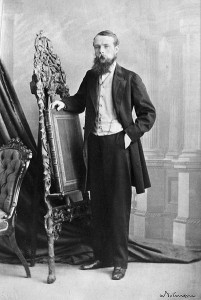

It was during this time that power moved from the hands of the aristocracy and “old money” to the new class of rising bourgeoisie who amassed fortunes in their lifetimes. A new cadre of financiers and industrialists (like Donald Smith [1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal] and George Stephen [1st Baron Mount Stephen] in Canada) became the new power players, using their influence in business to control aspects of government as well. Eventually, concerns over the exploitation of workers led to the formation of labour unions and laws that set mandatory conditions for employees. Although the introduction of new technology at the end of the 20th century ended the industrial age, much of our social structure and social ideas—like the nuclear family, left-right political divisions, and time standardization—have a basis in industrial society.

Postindustrial Society

Information societies, sometimes known as postindustrial or digital societies, are a recent development. Unlike industrial societies that are rooted in the production of material goods, information societies are based on the production of information and services.

Digital technology is the steam engine of information societies, and high tech companies such as Apple and Microsoft are its version of railroad and steel manufacturing corporations. Since the economy of information societies is driven by knowledge and not material goods, power lies with those in charge of creating, storing, and distributing information. Members of a postindustrial society are likely to be employed as sellers of services—software programmers or business consultants, for example—instead of producers of goods. Social classes are divided by access to education, since without technical and communication skills, people in an information society lack the means for success.

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

While many sociologists have contributed to research on society and social interaction, three thinkers form the base of modern-day perspectives. Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber developed different theoretical approaches to help us understand the formation of modern industrial society.

Émile Durkheim and Functionalism

As a functionalist, Émile Durkheim’s (1858–1917) perspective on society stressed the necessary interconnectivity of all of its elements. To Durkheim, society was greater than the sum of its parts. He asserted that individual behaviour was not the same as collective behaviour, and that studying collective behaviour was quite different from studying an individual’s actions. Society acted as an external restraint on individual behaviour. In his quest to understand what causes individuals to act in similar and predictable ways, he wrote, “If I do not submit to the conventions of society, if in my dress I do not conform to the customs observed in my country and in my class, the ridicule I provoke, the social isolation in which I am kept, produce, although in an attenuated form, the same effects as punishment” (Durkheim 1895). Durkheim called the communal beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society the collective conscience.

Durkheim also believed that social integration, or the strength of ties that people have to their social groups, was a key factor in social life. Following the ideas of Comte and Spencer, Durkheim likened society to that of a living organism, in which each organ plays a necessary role in keeping the being alive. Even the socially deviant members of society are necessary, Durkheim argued, as punishments for deviance affirm established cultural values and norms. That is, punishment of a crime reaffirms our moral consciousness. “A crime is a crime because we condemn it,” Durkheim wrote in 1893. “An act offends the common consciousness not because it is criminal, but it is criminal because it offends that consciousness” (Durkheim 1893). Durkheim called these elements of society “social facts.” By this, he meant that social forces were to be considered real and existed outside the individual.

As an observer of his contemporary social world, particularly the fractious late 19th century history of France, Durkheim was concerned with indications that modern society was in a process of social disintegration. His primary concern was that the cultural glue that held society together was failing, and that people were becoming more divided. In his book The Division of Labour in Society (1893), Durkheim argued that as society grew more populated, more complex, and more difficult to regulate, the underlying basis of solidarity or unity within the social order needed to evolve.

Preindustrial societies, Durkheim explained, were held together by mechanical solidarity, a type of social order maintained through a minimal division of labour and a common collective consciousness. Such societies permitted a low degree of individual autonomy. Essentially there was no distinction between the individual conscience and the collective conscience. Societies with mechanical solidarity act in a mechanical fashion; things are done mostly because they have always been done that way. If anyone violated the collective conscience embodied in laws and taboos, punishment was swift and retributive. This type of thinking was common in preindustrial societies where strong bonds of kinship and a low division of labour created shared morals and values among people, such as hunter-gatherer groups. When people tend to do the same type of work, Durkheim argued, they tend to think and act alike.

In industrial societies, mechanical solidarity is replaced with organic solidarity, social order based around an acceptance of economic and social differences. In capitalist societies, Durkheim wrote, division of labour becomes so specialized that everyone is doing different things. Even though there is an increased level of individual autonomy—unique “personalities” and individualism—society coheres because everyone depends on everyone else. Instead of punishing members of a society for failure to assimilate to common values, organic solidarity allows people with differing values to coexist. Laws exist as formalized morals and are based on restitution rather than retribution or revenge.

While the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity is, in the long run, advantageous for a society, Durkheim noted that it can be a time of chaos and “normlessness.” One of the outcomes of the transition is social anomie. Anomie—literally, “without norms”—is a situation in which society no longer has the support of a firm collective consciousness. There are no clear norms or values to guide and regulate behaviour. Anomie was associated with the rise of industrial society, which removed traditional modes of moral regulation; the rise of individualism, which removed limits on what individuals could desire; and the rise of secularism, which removed ritual or symbolic foci. During times of war or rapid economic development, the normative basis of society was also challenged. People isolated in their specialized tasks tend to become alienated from one another and from a sense of collective conscience. However, Durkheim felt that as societies reach an advanced stage of organic solidarity, they avoid anomie by redeveloping a set of shared norms. According to Durkheim, once a society achieves organic solidarity, it has finished its development.

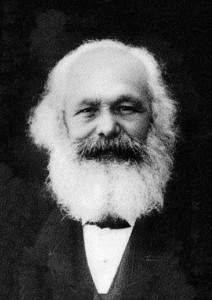

Karl Marx and Critical Sociology

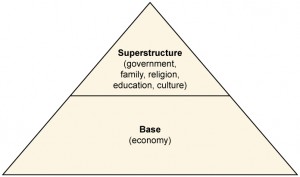

Karl Marx (1818–1883) offered one of the most comprehensive theories of the development of human societies from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the modern industrial age. For Marx, the underlying structure of societies and of the forces of historical change was predicated on the idea of “base and superstructure.” In this model, a society’s economic structure forms its base, on which the culture and social institutions rest, forming its superstructure. For Marx, it is the base—the economic mode of production—that determines what a society’s culture, law, political system, family form, and, most importantly, its typical form of struggle or conflict will be like. Each type of society—hunter-gatherer, pastoral, agrarian, feudal, capitalist—could be characterized as the total way of life that forms around different economic bases.

Marx saw economic conflict in society as the primary means of change. The base of each type of society in history—its economic mode of production—had its own characteristic form of economic struggle. This was because a mode of production was essentially two things: the means of production of a society—anything that is used in production to satisfy needs and maintain existence (e.g., land, animals, tools, machinery, factories, etc.)—and the relations of production of a society—the division of society into economic classes (the social roles allotted to individuals in production). Marx observed historically that in each epoch or type of society, only one class of persons has owned or monopolized the means of production. Different epochs are characterized by different forms of ownership and different class structures: hunter-gatherer (classless/common ownership), agricultural (citizens/slaves), feudal (lords/peasants), and capitalism (capitalists/“free” labourers). As a result, the relations of production have been characterized by relations of domination since the emergence of private property. Throughout history, classes have had opposed or contradictory interests. These “class antagonisms,” as he called them, periodically lead to periods of social revolution in which it becomes possible for one type of society to replace another.

The most recent revolutionary transformation resulted in the end of feudalism. A new revolutionary class emerged from among the freemen, small property owners, and middle-class burghers of the medieval period to challenge and overthrow the privilege and power of the feudal aristocracy. The members of the bourgeoisie or capitalist class were revolutionary in the sense that they represented a radical change and redistribution of power in European society. Their power was based in the private ownership of industrial property, which they sought to protect through the struggle for property rights, notably in the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the French Revolution (1789—1799). The development of capitalism inaugurated a period of world transformation and incessant change through the destruction of the previous class structure, the ruthless competition for markets, the introduction of new technologies, and the globalization of economic activity. As Marx and Engels put it in The Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors”, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation…. The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society…. Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind (1848).

However, the rise of the bourgeoisie and the development of capitalism also brought into existence the class of “free” wage labourers, or the proletariat. The proletariat were made up largely of guild workers and serfs who were freed or expelled from their indentured labour in feudal guild and agricultural production and migrated to the emerging cities where industrial production was centred. They were “free” labour in the sense that they were no longer bound to feudal lords or guildmasters. The new labour relationship was based on a contract. However, as Marx pointed out, this meant in effect that workers could sell their labour as a commodity to whomever they wanted, but if they did not sell their labour they would starve. The capitalist had no obligations to provide them with security, livelihood, or a place to live as the feudal lords had done for their serfs. The source of a new class antagonism developed based on the contradiction of fundamental interests between the bourgeois owners and the wage labourers: where the owners sought to reduce the wages of labourers as far as possible to reduce the costs of production and remain competitive, the workers sought to retain a living wage that could provide for a family and secure living conditions. The outcome, in Marx and Engel’s words, was that “society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other—Bourgeoisie and Proletariat” (1848).

In the mid-19th century, as industrialization was booming, the conditions of labour became more and more exploitative. The large manufacturers of steel were particularly ruthless, and their facilities became popularly dubbed “satanic mills” based on a poem by William Blake. Marx’s colleague and friend, Frederick Engels, wrote The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844, which described in detail the horrid conditions.

Such is the Old Town of Manchester, and on re-reading my description, I am forced to admit that instead of being exaggerated, it is far from black enough to convey a true impression of the filth, ruin, and uninhabitableness, the defiance of all considerations of cleanliness, ventilation, and health which characterise the construction of this single district, containing at least twenty to thirty thousand inhabitants. And such a district exists in the heart of the second city of England, the first manufacturing city of the world (1812).

Add to that the long hours, the use of child labour, and exposure to extreme conditions of heat, cold, and toxic chemicals, and it is no wonder that Marx referred to capital as “dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks” (Marx 1867).

For Marx, what we do defines who we are. What it is to be “human” is defined by the capacity we have as a species to creatively transform the world in which we live in to meet our needs for survival. Humanity at its core is Homo faber (“Man the Creator”). In historical terms, in spite of the persistent nature of one class dominating another, the element of humanity as creator existed. There was at least some connection between the worker and the product, augmented by the natural conditions of seasons and the rising and setting of the sun, such as we see in an agricultural society. But with the bourgeois revolution and the rise of industry and capitalism, workers now worked for wages alone. The essential elements of creativity and self-affirmation in the free disposition of their labour was replaced by compulsion. The relationship of workers to their efforts was no longer of a human nature, but based on purely animal needs. As Marx put it, the worker “only feels himself freely active in his animal functions of eating, drinking and procreating, at most also in his dwelling and dress, and feels himself an animal in his human functions” (1932).

Marx described the economic conditions of production under capitalism in terms of alienation. Alienation refers to the condition in which the individual is isolated and divorced from his or her society, work, or the sense of self and common humanity. Marx defined four specific types of alienation that arose with the development of wage labour under capitalism.

Alienation from the product of one’s labour. An industrial worker does not have the opportunity to relate to the product he or she is labouring on. The worker produces commodities, but at the end of the day the commodities not only belong to the capitalist, but serve to enrich the capitalist at the worker’s expense. In Marx’s language, the worker relates to the product of his or her labour “as an alien object that has power over him [or her]” (1932). Workers do not care if they are making watches or cars; they care only that their jobs exist. In the same way, workers may not even know or care what products they are contributing to. A worker on a Ford assembly line may spend all day installing windows on car doors without ever seeing the rest of the car. A cannery worker can spend a lifetime cleaning fish without ever knowing what product they are used for.

Alienation from the process of one’s labour. Workers do not control the conditions of their jobs because they do not own the means of production. If someone is hired to work in a fast food restaurant, that person is expected to make the food the way as taught. All ingredients must be combined in a particular order and in a particular quantity; there is no room for creativity or change. An employee at Burger King cannot decide to change the spices used on the fries in the same way that an employee on a Ford assembly line cannot decide to place a car’s headlights in a different position. Everything is decided by the owners who then dictate orders to the workers. The workers relate to their own labour as an activity that does not belong to them.

Alienation from others. Workers compete, rather than cooperate. Employees vie for time slots, bonuses, and job security. Different industries and different geographical regions compete for investment. Even when a worker clocks out at night and goes home, the competition does not end. As Marx commented in The Communist Manifesto, “No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by the other portion of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker” (1848).

Alienation from one’s humanity. A final outcome of industrialization is a loss of connectivity between a worker and what makes him or her truly human. Humanity is defined for Marx by “conscious life-activity” but under conditions of wage labour this is taken not as an end in itself but only as a means of satisfying the most base animal-like needs. The “species being” (i.e., conscious activity) is only confirmed when individuals can create and produce freely, not simply when they work to reproduce their existence and satisfy immediate needs like animals.

Taken as a whole, then, alienation in modern society means that individuals have no control over their lives. There is nothing that ties workers to their occupations. Instead of being able to take pride in an identity such as being a watchmaker, automobile builder, or chef, a person is simply a cog in the machine. Even in feudal societies, people controlled the manner of their labour as to when and how it was carried out. But why, then, does the modern working class not rise up and rebel?

In response to this problem, Marx developed the concept of false consciousness. False consciousness is a condition in which the beliefs, ideals, or ideology of a person are not in the person’s own best interest. In fact, it is the ideology of the dominant class (here, the bourgeoisie capitalists) that is imposed upon the proletariat. Ideas such as the emphasis of competition over cooperation, of hard work being its own reward, of individuals as being the isolated masters of their own fortunes and ruins, etc. clearly benefit the owners of industry. Therefore, to the degree that workers live in a state of false consciousness, they are less likely to question their place in society and assume individual responsibility for existing conditions.

As “consciousness,” like other elements of the superstructure, are products of the underlying economic Marx proposed that the workers’ false consciousness would eventually be replaced with class consciousness, the awareness of their actual material and political interests as members of a unified class. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote,

The weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself. But not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians (1848).

As capitalism developed the industrial means by which the problems of economic scarcity could be resolved, while at the same time intensifying the conditions of exploitation due to competition for markets and profits, the conditions for a successful working class revolution would emerge. Instead of existing as an unconscious “class in itself,” the proletariat would become a “class for itself” and act collectively to produce social change (Marx and Engels 1848). Instead of just being an inert strata of society, the class could become an advocate for social improvements. Only once society entered this state of political consciousness would it be ready for a social revolution. Indeed, Marx predicted that this would be the ultimate outcome and collapse of capitalism.

Max Weber and Rationalization

Like the other social thinkers discussed here, Max Weber (1864–1920) was concerned with the important changes taking place in Western society with the advent of capitalism. Like Marx and Durkheim, he feared that capitalist industrialization would have negative effects on individuals.

Weber’s analysis of modern society centred on the concept of rationalization. Arguably, the primary focus of Weber’s entire sociological oeuvre was to determine how and why Western civilization and capitalism developed where and when they did. Why was the West the West? Key to his answer was that rationalization did not develop in the same way elsewhere as it did in Western society. Rationalization refers to the general tendency in modern society for all institutions and most areas of life to be transformed by the application of rationality. It overcomes forms of magical thinking and replaces them with calculation. A rational society is one built around rational forms of organization, technology, and efficiency rather than religion, morality, or tradition. Older styles of social organization, whether political, economic, military, or what have you, based on other principles, could not compete with the efficiency of rational styles of organization and were gradually replaced. Weber’s question was, what are the consequences of rationality for everyday life, for the social order, and for the spiritual fate of humanity?

To Weber, capitalism became possible through the processes of rationalization. He defined capitalism as a type of continuous, calculated economic action in which every element was examined with respect to the logic of investment and return. As opposed to previous types of economic action in which wealth was acquired by force, capitalism rested “on the expectation of profit by the utilization of opportunities for exchange, that is on (formally) peaceful chances for profit….Where capitalist acquisition is rationally pursued, the corresponding action is adjusted to calculations in terms of capital” (Weber 1904). Capitalism required the prior existence of rational procedures like double-entry bookkeeping, free market enterprise, free labour contracts, free market exchange, and calculable law so that it could operate as a form of rational enterprise.

Weber argued that although this leads to efficiency and rational, calculated decision making, it is in the end an irrational system. The emphasis on rationality and efficiency ultimately has negative effects when taken to the extreme. In modern societies, this is seen when rigid routines and strict adherence to performance-related goals lead to a mechanized work environment and a focus on efficiency for its own sake. To the degree that rational efficiency begins to undermine the substantial human values it was designed to serve (i.e., the ideals of the good life) rationalization becomes irrational.

An example of the extreme conditions of rationality can be found in Charlie Chaplin’s classic film Modern Times (1936). Chaplin’s character works on an assembly line twisting a bolts into place over and over again. When he has to stop to swat a fly on his nose all the tasks down the line from him are thrown into disarray. He performs his routine task to the point where he cannot stop his jerking motions even after the whistle blows for lunch. Indeed, today we even have a recognized medical condition that results from such tasks, known as “repetitive stress syndrome.”

For Weber, the culmination of industrialization and rationalization results in what he referred to as the iron cage, in which the individual is trapped by the systems of efficiency that were designed to enhance the well-being of humanity. It is a cage, or literally, from the original German, steel housing that we are encased in, because efficient rational forms of organization have become indispensable. Even if there was a social revolution of the type that Marx envisioned, the bureaucratic and rational organizational structures would remain. There appears to be no alternative. The modern economic order “is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which today determine the lives of all individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force” (Weber 1904).

This leads to a sense of “disenchantment of the world,” a phrase Weber used to describe the final condition of humanity (see Chapter 1). Indeed a dark prediction, but one that has, at least to some degree, been borne out. In a rationalized, modern society, we have supermarkets instead of family-owned stores. We have chain restaurants instead of local eateries. Superstores that offer a multitude of merchandise have replaced independent businesses that focused on one product line, such as hardware, groceries, automotive repair, or clothing. Shopping malls offer retail stores, restaurants, fitness centres, even condominiums. This change may be rational, but is it universally desirable?

Making Connections: Sociological Research

The Protestant Work Ethic

In a series of essays in 1904, Weber presented the idea of the Protestant work ethic, a new attitude toward work based on the Calvinist principle of predestination. In the 16th century, Europe was shaken by the Protestant Revolution. Religious leaders such as Martin Luther and John Calvin argued against the Catholic Church’s belief in salvation through obedience. While Catholicism, in principle at least, emphasized nonmaterialistic values—the importance of poverty, humility, chastity, and performance of good deeds—as a gateway to heaven, the new Protestant sects began to emphasize outward displays of hard work and self-discipline to “prove oneself” before God. The idea that one must “work hard in one’s calling” combined the materialist value of work (rewarded by fortune and standing in the community), with the spiritual value of attaining salvation.

John Calvin in particular popularized the Christian concept of predestination, the idea that all events—including salvation—have already been decided by God. Because followers were never sure whether they had been chosen to enter Heaven or Hell, they looked for signs in their everyday lives. People lived on a kind of permanent ethical probation. If a person was hard-working and successful, he or she was likely to be one of the chosen. If a person was lazy or simply indifferent, he or she was likely to be one of the damned.

Weber argued that this ethic provided the basis for a rationalized approach to life: “rational conduct on the basis of the idea of the calling” (Weber 1904). It encouraged people to work hard in a disciplined, methodical way for personal gain. Emphasis was placed on proving one’s state of inner grace to God and on proving one’s state of “election” to the wider community. “The God of Calvinism demanded of his believers not single good works, but a life of good works united into a unified system” (Weber 1904).

The irrational component of this, however, was that the spiritual goal of attaining salvation was gradually forgotten as the Protestant ethic was absorbed into the way of life of capitalism, and all that was left was the compulsion to work for work’s sake. As Weber famously put it at the end of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, “The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so,” (Weber 1904 ).

Her-story: The History of Gender Inequality

Missing in the classical theoretical accounts of modernity is an explanation of how the developments of modern society, industrialization, and capitalism have affected women differently from men. Despite the differences in Durkheim’s, Marx’s, and Weber’s main themes of analysis, they are equally androcentric to the degree that they cannot account for why women’s experience of modern society is structured differently from men’s, or why the implications of modernity are different for women than they are for men. They tell his-story but neglect her-story.

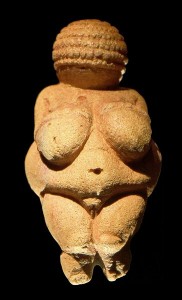

For most of human history, men and women held more or less equal status in society. In hunter-gatherer societies gender inequality was minimal as these societies did not sustain institutionalized power differences. They were based on cooperation, sharing, and mutual support. There was often a gendered division of labour in that men are most frequently the hunters and women the gatherers and child care providers (although this division is not necessarily strict), but as women’s gathering accounted for up to 80 percent of the food, their economic power in the society was assured. Where headmen do lead tribal life, their leadership is informal, based on influence rather than institutional power (Endicott 1999). In prehistoric Europe from 7000 to 3500 BCE, archaeological evidence indicates that religious life was in fact focused on female deities and fertility, while family kinship was traced through matrilineal (female) descent (Lerner 1986).

It was not until about 6,000 years ago that gender inequality emerged. With the transition to early agrarian and pastoral types of societies, food surpluses created the conditions for class divisions and power structures to develop. Property and resources passed from collective ownership to family ownership with a corresponding shift in the development of the monogamous, patriarchal (rule by the father) family structure. Women and children also became the property of the patriarch of the family. The invasions of old Europe by the Semites to the south and the Kurgans to the northeast led to the imposition of male-dominated hierarchical social structures and the worship of male warrior gods. As agricultural societies developed, so did the practice of slavery. Lerner (1986) argues that the first slaves were women and children.

The development of modern, industrial society has been a two-edged sword in terms of the status of women in society. Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) argued in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884) that the historical development of the male-dominated monogamous family originated with the development of private property. The family became the means through which property was inherited through the male line. This also led to the separation of a private domestic sphere and a public social sphere. “Household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a private service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production” (1884). Under the system of capitalist wage labour, women were doubly exploited. When they worked outside the home as wage labourers they were exploited in the workplace, often as cheaper labour than men. When they worked within the home, they were exploited as the unpaid source of labour needed to reproduce the capitalist workforce. The role of the proletarian housewife was tantamount to “open or concealed domestic slavery” as she had no independent source of income herself (Engels 1884). Early Canadian law, for example, was based on the idea that the wife’s labour belonged to the husband. This was the case even up to the divorce case of Irene Murdoch in 1973, who had worked the family farm in the Turner Valley, Alberta, side by side with her husband for 25 years. When she claimed 50 percent of the farm assets in the divorce, the judge ruled the farm belonged to her husband, and she was awarded only $200 a month for a lifetime of work (CBC 2001).

On the other hand, feminists note that gender inequality was more pronounced and permanent in the feudal and agrarian societies that proceeded capitalism. Women were more or less owned as property, kept ignorant and isolated within the domestic sphere. (These types of society still exist today, of course.) Engels also noted that there was an improvement in women’s condition when she was able to work outside the home. Writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) in her Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) were able to see in the discourses of rights and freedoms of the bourgeois revolutions and the Enlightenment, a general “promise” of universal emancipation that could be extended to include the rights of women. The focus of the Vindication of the Rights of Women was on the right of women to have an education, which would put them on the same footing as men with regard to the knowledge and rationality required for “enlightened” political participation and skilled work outside the home. Whereas property rights, the role of wage labour, and the law of modern society continued to be a source for gender inequality, the principles of universal rights became a powerful resource for women to use to press their claims for equality.

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

Until now, we’ve primarily discussed the differences between types of societies from a macro-perspective. Rather than discuss their problems and configurations, we will now explore how society came to be and how sociologists view social interaction from a micro-perspective.

In 1966 sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann wrote The Social Construction of Reality. In it, they argued that society is created by humans and human interaction, which they call habitualization. Habitualization describes how “any action that is repeated frequently becomes cast into a pattern, which can then be … performed again in the future in the same manner and with the same economical effort” (Berger and Luckmann 1966). Not only do we construct our own society, but we accept it as it is because others have created it before us. Society is, in fact, “habit.”

For example, your school exists as a school and not just as a building because you and others agree that it is a school. If your school is older than you are, it was created by the agreement of others before you. In a sense, it exists by consensus, both prior and current. This is an example of the process of institutionalization, the act of implanting a convention or norm into society. Bear in mind that the institution, while socially constructed, is still quite real.

Another way of looking at this concept is through W. I. Thomas’s notable Thomas theorem which states, “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928). That is, people’s behaviour can be determined by their subjective construction of reality rather than by objective reality. For example, a teenager who is repeatedly given a label—overachiever, player, bum—might live up to the term even though it initially was not a part of his or her character.

Like Berger and Luckmann’s description of habitualization, Thomas states that our moral codes and social norms are created by “successive definitions of the situation.” This concept is defined by sociologist Robert K. Merton as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Merton explains that with a self-fulfilling prophecy, even a false idea can become true if it is acted on. One example he gives is of a “bank run.” Say for some reason, a number of people falsely fear that their bank is soon to be bankrupt. Because of this false notion, people run to their bank and demand all their cash at once. As banks rarely, if ever, have that much money on hand, the bank does indeed run out of money, fulfilling the customers’ prophecy. On the other hand, “investor confidence” is another social construct, which as we saw in the lead up to the financial crisis of 2008, is “real in its consequences” but based on a fiction. Reality is constructed by an idea.

Roles and Status

As you can imagine, people employ many types of behaviours in day-to-day life. Roles are patterns of behaviour that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status. Currently, while reading this text, you are playing the role of a student. However, you also play other roles in your life, such as “daughter,” “neighbour,” or “employee.” These various roles are each associated with a different status.

Sociologists use the term status to describe the access to resources and benefits a person experiences according to the rank or prestige of his or her role in society. Some statuses are ascribed—those you do not select, such as son, elderly person, or female. Others, called achieved statuses, are obtained by personal effort or choice, such as a high school dropout, self-made millionaire, or nurse. As a daughter or son, you occupy a different status than as a neighbour or employee. One person can be associated with a multitude of roles and statuses. Even a single status such as “student” has a complex role-set, or array of roles, attached to it (Merton 1957).

If too much is required of a single role, individuals can experience role strain. Consider the duties of a parent: cooking, cleaning, driving, problem solving, acting as a source of moral guidance—the list goes on. Similarly, a person can experience role conflict when one or more roles are contradictory. A parent who also has a full-time career can experience role conflict on a daily basis. When there is a deadline at the office but a sick child needs to be picked up from school, which comes first? When you are working toward a promotion but your children want you to come to their school play, which do you choose? Being a college student can conflict with being an employee, being an athlete, or even being a friend. Our roles in life have a great effect on our decisions and who we become.

Presentation of Self

Of course, it is impossible to look inside a person’s head and study what role he or she is playing. All we can observe is behaviour, or role performance. Role performance is how a person expresses his or her role. Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman presented the idea that a person is like an actor on a stage. Calling his theory “dramaturgy,” Goffman believed that we use “impression management” to present ourselves to others as we hope to be perceived. The positive value that we would claim for ourselves depends crucially on whether others accept the credibility of our performance. Each situation is a new scene, and individuals perform different roles depending on who is present (Goffman 1959). Think about the way you behave around your coworkers versus the way you behave around your grandparents versus the way you behave with a blind date. Even if you’re not consciously trying to alter your personality, your grandparents, coworkers, and date probably see different sides of you.

As in a play, the setting matters as well. If you have a group of friends over to your house for dinner, you are playing the role of a host. It is agreed upon that you will provide food and seating and probably be stuck with a lot of the cleanup at the end of the night. Similarly, your friends are playing the roles of guests, and they are expected to respect your property and any rules you may set forth (“Don’t leave the door open or the cat will get out.”). In any scene, there needs to be a shared reality between players. In this case, if you view yourself as a guest and others view you as a host, there are likely to be problems.

Impression management is a critical component of symbolic interactionism. For example, a judge in a courtroom has many “props” to create an impression of fairness, gravity, and control—like a robe and gavel. Those entering the courtroom are expected to adhere to the scene being set. Just imagine the “impression” that can be made by how a person dresses. This is the reason that attorneys frequently select the hairstyle and apparel for witnesses and defendants in courtroom proceedings.

Goffman’s dramaturgy ideas expand on the ideas of Charles Cooley and the looking-glass self. According to Cooley, we base our image on what we think other people see (Cooley 1902). We imagine how we must appear to others, then react to this speculation. We don certain clothes, prepare our hair in a particular manner, wear makeup, use cologne, and the like—all with the notion that our presentation of ourselves is going to affect how others perceive us. We expect a certain reaction, and, if lucky, we get the one we desire and feel good about it. Cooley believed that our sense of self is not based on some internal source of individuality. Rather, we imagine how we look to others, draw conclusions based on their reactions to us, and then develop our personal sense of self. In other words, people’s reactions to us are like a mirror in which we are reflected. We live a mirror image of ourselves. “The imaginations people have of one another are the solid facts of society” (Cooley 1902).

Key Terms

achieved statuses obtained by personal effort or choice, such as a high school dropout, self-made millionaire, or nurse

alienation the condition in which an individual is isolated from his or her society, work, or the sense of self and common humanity

anomie a situation in which society no longer has the support of a firm collective consciousness

ascribed status the status outside of an individual’s control, such as sex or race

bourgeoisie the owners of the means of production in a society

class consciousness awareness of one’s rank in society

collective conscience the communal beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society

false consciousness when a person’s beliefs and ideology are in conflict with his or her best interests

feudal societies societies that operate on a strict hierarchical system of power based around land ownership and protection

habitualization the idea that society is constructed by us and those before us, and it is followed like a habit

horticultural societies societies based around the cultivation of plants

hunter-gatherer societies societies that depend on hunting wild animals and gathering uncultivated plants for survival

industrial societies societies characterized by a reliance on mechanized labour to create material goods

information societies societies based on the production of nonmaterial goods and services

institutionalization the act of implanting a convention or norm into society

iron cage a situation in which an individual is trapped by social institutions

looking-glass self our reflection of how we think we appear to others

mechanical solidarity a type of social order maintained by the collective consciousness of a culture

organic solidarity a type of social order based around an acceptance of economic and social differences

pastoral societies societies based around the domestication of animals

proletariat the labourers in a society

rationalization the general tendency in modern society for all institutions and most areas of life to be transformed by the application of rationality and efficiency

role conflict when one or more of an individual’s roles clash

role performance the expression of a role

role strain stress that occurs when too much is required of a single role

role-set an array of roles attached to a particular status

roles patterns of behaviour that are representative of a person’s social status

self-fulfilling prophecy an idea that becomes true when acted on

social integration how strongly a person is connected to his or her social group

status the responsibilities and benefits that a person experiences according to his or her rank and role in society

Thomas theorem how a subjective reality can drive events to develop in accordance with that reality, despite being originally unsupported by objective reality

Section Summary

4.1. Types of Societies

Societies are classified according to their development and use of technology. For most of human history, people lived in preindustrial societies characterized by limited technology and low production of goods. After the Industrial Revolution, many societies based their economies around mechanized labour, leading to greater profits and a trend toward greater social mobility. At the turn of the new millennium, a new type of society emerged. This postindustrial, or information, society is built on digital technology and nonmaterial goods.

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

Émile Durkheim believed that as societies advance, they make the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity. For Karl Marx, society exists in terms of class conflict. With the rise of capitalism, workers become alienated from themselves and others in society. Sociologist Max Weber noted that the rationalization of society can be taken to unhealthy extremes. Feminists note that the androcentric point of view of the classical theorists does not provide an adequate account of the difference in the way the genders experience modern society.

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

Society is based on the social construction of reality. How we define society influences how society actually is. Likewise, how we see other people influences their actions as well as our actions toward them. We all take on various roles throughout our lives, and our social interactions depend on what types of roles we assume, who we assume them with, and the scene where interaction takes place.

Section Quiz

4.1. Types of Societies

1. Which of the following fictional societies is an example of a pastoral society?

- the Deswan people, who live in small tribes and base their economy on the production and trade of textiles

- the Rositian Clan, a small community of farmers who have lived on their family’s land for centuries

- the Hunti, a wandering group of nomads who specialize in breeding and training horses

- the Amaganda, an extended family of warriors who serve a single noble family

2. Which of the following occupations is a person of power most likely to have in an information society?

- software engineer

- coal miner

- children’s book author

- sharecropper

3. Which of the following societies were the first to have permanent residents?

- industrial

- hunter-gatherer

- horticultural

- feudal

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

4. Organic solidarity is most likely to exist in which of the following types of societies?

- hunter-gatherer

- industrial

- agricultural

- feudal

5. According to Marx, the _____ own the means of production in a society.

- proletariat

- vassals

- bourgeoisie

- anomie

6. Which of the following best depicts Marx’s concept of alienation from the process of one’s labour?

- A supermarket cashier always scans store coupons before company coupons because she was taught to do it that way.

- A businessman feels that he deserves a raise, but is nervous to ask his manager for one; instead, he comforts himself with the idea that hard work is its own reward.

- An associate professor is afraid that she won’t be given tenure and starts spreading rumours about one of her associates to make herself look better.

- A construction worker is laid off and takes a job at a fast food restaurant temporarily, although he has never had an interest in preparing food before.

7. The Protestant work ethic is based on the concept of predestination, which states that ________.

- performing good deeds in life is the only way to secure a spot in Heaven

- salvation is only achievable through obedience to God

- no person can be saved before he or she accepts Jesus Christ as his or her saviour

- God has already chosen those who will be saved and those who will be damned

8. The concept of the iron cage was popularized by which of the following sociological thinkers?

- Max Weber

- Karl Marx

- Émile Durkheim

- Friedrich Engels

9. Émile Durkheim’s ideas about society can best be described as ________.

- functionalist

- conflict theorist

- symbolic interactionist

- rationalist

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

10. Mary works full-time at an office downtown while her young children stay at a neighbour’s house. She’s just learned that the child care provider is leaving the country. Mary has succumbed to pressure to volunteer at her church, plus her ailing mother-in-law will be moving in with her next month. Which of the following is likely to occur as Mary tries to balance her existing and new responsibilities?

- role strain

- self-fulfilling prophecy

- status conflict

- status strain

11. According to Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, society is based on ________.

- habitual actions

- status

- institutionalization

- role performance

12. Paco knows that women find him attractive, and he’s never found it hard to get a date. But as he ages, he dyes his hair to hide the grey and wears clothes that camouflage the weight he has put on. Paco’s behaviour can be best explained by the concept of ___________.

- role strain

- the looking-glass self

- role performance

- habitualization

Short Answer

- How can the difference in the way societies relate to the environment be used to describe the different types of societies that have existed in world history?

- Is Gerhard Lenski right in classifying societies based on technological advances? What other criteria might be appropriate, based on what you have read?

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

- How might Durkheim, Marx, and Weber be used to explain a current social event such as the Occupy movement. Do their theories hold up under modern scrutiny? Are their theories necessarily androcentric?

- Think of the ways workers are alienated from the product and process of their jobs. How can these concepts be applied to students and their educations?

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

- Draw a large circle and then “slice” the circle into pieces like a pie, labelling each piece with a role or status that you occupy. Add as many statuses, ascribed and achieved, that you have. Don’t forget things like dog owner, gardener, traveller, student, runner, employee. How many statuses do you have? In which ones are there role conflicts?

- Think of a “self-fulfilling prophecy” that you have experienced. Based on this experience, do you agree with the Thomas theorem? What are the implications of the Thomas theorem for the difference between studying natural as opposed to social phenomena? Or is there a difference?

Further Research

4.1. Types of Societies

The Maasai are a modern pastoral society with an economy largely structured around herds of cattle. Read more about the Maasai people and see pictures of their daily lives here: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/The-Maasai

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

One of the most influential pieces of writing in modern history was Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto. Visit this site to read the original document that spurred revolutions around the world: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Communist-Party

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

TV Tropes is a website where users identify concepts that are commonly used in literature, film, and other media. Although its tone is for the most part humorous, the site provides a good jumping-off point for research. Browse the list of examples under the entry of “self-fulfilling prophecy.” Pay careful attention to the real-life examples. Are there ones that surprised you or that you don’t agree with? http://openstaxcollege.org/l/tv-tropes

References

4.. Introduction to Society and Social Interaction

Maasai Association. “Facing the Lion.” Retrieved January 4, 2012 (http://www.maasai-association.org/lion.html).

4.1. Types of Societies

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 2005. “Israel: Treatment of Bedouin, Including Incidents of Harassment, Discrimination or Attacks; State Protection (January 2003–July 2005)”, Refworld, July 29. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/440ed71325.html).

Kjeilen, Tore. N.d. “Bedouin.” Looklex.com. Retrieved February 17, 2012 (http://looklex.com/index.htm).

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Society

CBC. 2001. “Equal Under the Law: Canadian women fight for equality as the country creates a charter of rights” Canada: A People’s History. Retrieved February 21, 2014 (http://www.cbc.ca/history/EPISCONTENTSE1EP17CH2PA4LE.html).

Durkheim, Émile. 1960 [1893]. The Division of Labor in Society. Translated by George Simpson. New York: Free Press.

Durkheim, Émile. 1982 [1895]. The Rules of the Sociological Method. Translated by W. D. Halls. New York: Free Press.

Endicott, Karen. 1999. “Gender relations in hunter-gatherer societies.” Pp. 411–418 in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, edited by R.B. Lee and R. Daly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engels, Friedrich. 1972 [1884]. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. New York: International Publishers.

Engels, Friedrich. 1892. The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Lerner, Gerda. 1986. The Creation of Patriarchy. New York: Oxford Press.

Marx, Karl. 1995 [1867]. Capital. Marx/Engels Internet Archive. Retrieved February 18, 2014 (https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/).

Marx, Karl. 1977 [1932]. “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts.” Pp. 75–112 in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, edited by David McLellan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 1977 [1848]. The Communist Manifesto (Selections). Pp. 221–247 in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, edited by David McLellan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weber, Max. 1958 [1904]. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

4.3. Social Constructions of Reality

Berger, P. L. and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Cooley, Charles H. 1902. Human Nature and the Social Order. New York: Scribner’s.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self In Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

Merton, Robert K. 1957. “The Role-Set: Problems in Sociological Theory.” British Journal of Sociology 8(2):110–113.

Thomas, W. I. and D. S. Thomas. 1928. The Child in America: Behavior Problems and Programs. New York: Knopf.

Solutions to Section Quiz

1. C | 2. A | 3. C | 4. B | 5. C | 6. A | 7. D | 8. A | 9. A | 10. A | 11. A | 12. B

Image Attributions

Figure 4.4. Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 23 by Myrabella (http://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene23_Harold_oath_William.jpg) is in the public domain (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en)

Figure 4.5. George Stephen, 1965 by William Notman (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Stephen_1865.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 4.6. Image of the T. Eaton Co. department store in Toronto, Ontario, Canada from the back cover of the 1901 Eaton’s catalogue ( http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bird%27s_eye_view_of_the_store_and_factories_of_the_T._Eaton_Co._Limited_Toronto_Canada.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 4.10. Charlie Chaplin by Insomnia Cured Here (https://www.flickr.com/photos/tom-margie/1535417993/) used under CC BY SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

Figure 4.11. I Love Cubicles by Tim Patterson (https://www.flickr.com/photos/timpatterson/476098132/) used under CC BY 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Figure 4.12. Venus of Willendorf by MatthiasKabel (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Venus_of_Willendorf_frontview_retouched_2.jpg) used under CC BY SA 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)