Main Body

Chapter 18. Work and the Economy

Learning Objectives

- Understand types of economic systems and their historical development.

- Describe capitalism and socialism both in theory and in practice.

- Discussion how functionalists, critical sociologists, and symbolic interactionists view the economy and work.

- Describe the current Canadian workforce and the trend of polarization.

- Explain how women and immigrants have impacted the modern Canadian workforce.

- Understand the basic elements of poverty in Canada today.

Introduction to Work and the Economy

Ever since the first people traded one item for another, there has been some form of economy in the world. It is how people optimize what they have to meet their wants and needs. Economy refers to the social institutions through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed. Goods are the physical objects we find, grow, or make in order to meet our needs and the needs of others. Goods can meet essential needs, such as a place to live, clothing, and food, or they can be luxuries — those things we do not need to live but want anyway. Goods produced for sale on the market are called commodities. In contrast to these objects, services are activities that benefit people. Examples of services include food preparation and delivery, health care, education, and entertainment. These services provide some of the resources that help to maintain and improve a society. The food industry helps ensure that all of a society’s members have access to sustenance. Health care and education systems care for those in need, help foster longevity, and equip people to become productive members of society. Economy is one of human society’s earliest social structures. Our earliest forms of writing (such as Sumerian clay tablets) were developed to record transactions, payments, and debts between merchants. As societies grow and change, so do their economies. The economy of a small farming community is very different from the economy of a large nation with advanced technology. In this chapter, we will examine different types of economic systems and how they have functioned in various societies.

18.1 Economic Systems

The dominant economic systems of the modern era have been capitalism and socialism, and there have been many variations of each system across the globe. Countries have switched systems as their rulers and economic fortunes have changed. For example, Russia has been transitioning to a market-based economy since the fall of communism in that region of the world. Vietnam, where the economy was devastated by the Vietnam War, restructured to a state-run economy in response, and more recently has been moving toward a socialist-style market economy. In the past, other economic systems reflected the societies that formed them. Many of these earlier systems lasted centuries. These changes in economies raise many questions for sociologists. What are these older economic systems? How did they develop? Why did they fade away? What are the similarities and differences between older economic systems and modern ones?

Economics of Agricultural, Industrial, and Postindustrial Societies

Our earliest ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers. Small groups of extended families roamed from place to place looking for means to subsist. They would settle in an area for a brief time when there were abundant resources. They hunted animals for their meat and gathered wild fruits, vegetables, and cereals. They distributed and ate what they caught or gathered as soon as possible because they had no way of preserving or transporting it. Once the resources of an area ran low, the group had to move on, and everything they owned had to travel with them. Food reserves only consisted of what they could carry. Groups did not typically trade essential goods with other groups due to scarcity. The use of resources was governed by the practice of usufruct, the distribution of resources according to need. Bookchin (1982) notes that in hunter-gatherer societies “property of any kind, communal or otherwise, has yet to acquire independence from the claims of satisfaction” (p. 50).

The Agricultural Revolution

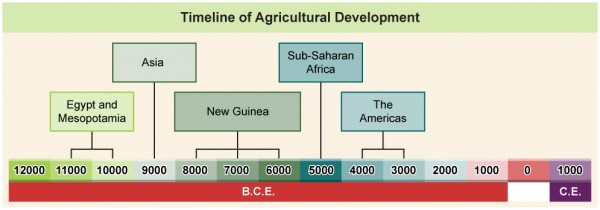

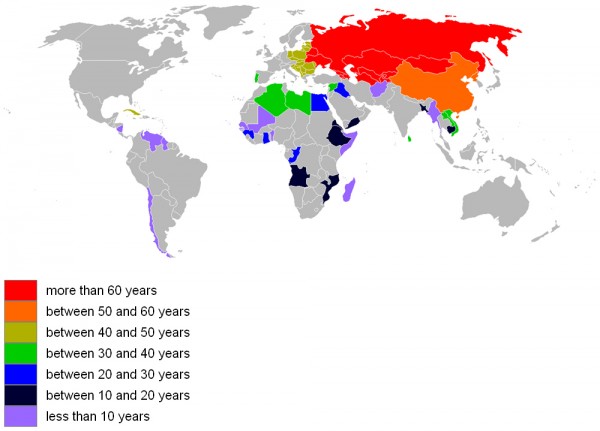

The first true economies arrived when people started raising crops and domesticating animals. Although there is still a great deal of disagreement among archeologists as to the exact timeline, research indicates that agriculture began independently and at different times in several places around the world. The earliest agriculture was in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East around 11,000–10,000 years ago. Next were the valleys of the Indus, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers in India and China, between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago. The people living in the highlands of New Guinea developed agriculture between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago, while people were farming in sub-Saharan Africa between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. Agriculture developed later in the western hemisphere, arising in what would become the eastern United States, central Mexico, and northern South America between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago (Diamond and Bellwood, 2003).

Agriculture began with the simplest of technologies — for example, a pointed stick to break up the soil — but really took off when people harnessed animals to pull an even more efficient tool for the same task: a plow. With this new technology, one family could grow enough crops not only to feed themselves but others as well. Knowing there would be abundant food each year as long as crops were tended led people to abandon the nomadic life of hunter-gatherers and settle down to farm. The improved efficiency in food production meant that not everyone had to toil all day in the fields. As agriculture grew, new jobs emerged, along with new technologies. Excess crops needed to be stored, processed, protected, and transported. Farming equipment and irrigation systems needed to be built and maintained. Wild animals needed to be domesticated and herds shepherded. Economies begin to develop because people now had goods and services to trade. As more people specialized in nonfarming jobs, villages grew into towns and then into cities. Urban areas created the need for administrators and public servants. Disputes over ownership, payments, debts, compensation for damages, and the like led to the need for laws and courts — and the judges, clerks, lawyers, and police who administered and enforced those laws.

At first, most goods and services were traded as gifts or through bartering between small social groups (Mauss, 1922). Exchanging one form of goods or services for another was known as bartering. This system only works when one person happens to have something the other person needs at the same time. To solve this problem, people developed the idea of a means of exchange that could be used at any time: that is, money. Money refers to an object that a society agrees to assign a value to so it can be exchanged for payment. In early economies, money was often objects like cowry shells, rice, barley, or even rum. Precious metals quickly became the preferred means of exchange in many cultures because of their durability and portability. The first coins were minted in Lydia in what is now Turkey around 650–600 BCE (Goldsborough, 2010). Early legal codes established the value of money and the rates of exchange for various commodities. They also established the rules for inheritance, fines as penalties for crimes, and how property was to be divided and taxed (Horne, 1915). A symbolic interactionist would note that bartering and money are systems of symbolic exchange. Monetary objects took on a symbolic meaning, one that carries into our modern-day use of cheques and debit cards.

Making Connections: Case Study

The Lady Who Lives without Money

Imagine having no money. If you wanted some french fries, needed a new pair of shoes, or were due to get an oil change for your car, how would you get those goods and services? This is not just a theoretical question. Think about it. What do those on the outskirts of society do in these situations? Think of someone escaping domestic abuse who gave up everything and has no resources. Or an immigrant who wants to build a new life but who had to leave another life behind to find that opportunity. Or a homeless person who simply wants a meal to eat. This last example, homelessness, is what caused Heidemarie Schwermer to give up money (2011). A divorced high school teacher in Germany, Schwermer’s life took a turn when she relocated her children to a rural town with a significant homeless population. She began to question what serves as currency in a society and decided to try something new. Schwermer founded a business called Gib und Nimm — in English, “give and take.” It operated on a moneyless basis and strived to facilitate people swapping goods and services for other goods and services — no cash allowed (Schwermer, 2007). What began as a short experiment has become a new way of life. Schwermer says the change has helped her focus on people’s inner value instead of their outward wealth. It has also led to two books telling her story (she’s donated all proceeds to charity) and, most importantly, a richness in her life she was unable to attain with money.

In the early 1980s, a similar system ran on Vancouver Island. Known as L.E.T.S. (Local Exchange Trading System), the system ran on the moneyless principle of exchanges of services (Boxall, 2006). People did not have to directly swap services or goods — “I’ll mow your lawn if you edit my English grammar” — but could provide goods or perform services and bank the credits in “green dollars” for later use. It was not meant to replace the money economy entirely but to supplement it and provide a means of support and economic activity, especially in times of paid work scarcity. The founder of the system in Courtenay, B.C., Michael Linton, said that the system petered out on the central island by the late 1980s (a group still exists in Victoria), but not before spreading to almost 3,000 communities around the world.

How might our three sociological perspectives view L.E.T.S. systems? What would most interest them about this form of unconventional economics? Would a functionalist consider them an aberration of norms or social dysfunction that upsets the normal balance, or would they note the substantial community building aspect of the direct provision of services and goods between people? How would a critical sociologist approach the concept of an alternative, moneyless economy? Is it a means of further exploiting labour or of escaping the alienation of commodified labour? What might a symbolic interactionist make of the choice not to use money — such an important symbol in the modern world? What do you make of Gib und Nimm?

As city-states grew into countries and countries grew into empires, their economies grew as well. When large empires broke up, their economies broke up too. The governments of newly formed nations sought to protect and increase their markets. They financed voyages of discovery to find new markets and resources all over the world, ushering in a rapid progression of economic development. Colonies were established to secure these markets, and wars were financed to take over territory. These ventures were funded in part by raising capital from investors who were paid back from the goods obtained. Governments and private citizens also set up large trading companies that financed their enterprises around the world by selling stocks and bonds. Governments tried to protect their share of the markets by developing a system called mercantilism. Mercantilism is an economic policy based on accumulating silver and gold by controlling colonial and foreign markets through taxes and other charges. The resulting restrictive practices and exacting demands included monopolies, bans on certain goods, high tariffs, and exclusivity requirements. Mercantilistic governments also promoted manufacturing and, with the ability to fund technological improvements, they helped create the equipment that led to the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution

Up until the end of the 18th century, most manufacturing was done using manual labour. This changed as research led to machines that could be used to manufacture goods. A small number of innovations led to a large number of changes in the British economy. In the textile industries, the spinning of cotton, worsted yarn, and flax could be done more quickly and less expensively using new machines with names like the Spinning Jenny and the Spinning Mule (Bond et al., 2003). Another important innovation was made in the production of iron: coke from coal could now be used in all stages of smelting rather than charcoal from wood, dramatically lowering the cost of iron production while increasing availability (Bond, 2003). James Watt ushered in what many scholars recognize as the greatest change, revolutionizing transportation and, thereby, the entire production of goods with his improved steam engine. As people moved to cities to fill factory jobs, factory production also changed. Workers did their jobs in assembly lines and were trained to complete only one or two steps in the manufacturing process. These advances meant that more finished goods could be manufactured with more efficiency and speed than ever before.

The Industrial Revolution also changed agricultural practices. Until that time, many people practiced subsistence farming in which they produced only enough to feed themselves and pay their taxes. New technology introduced gasoline-powered farm tools such as tractors, seed drills, threshers, and combine harvesters. Farmers were encouraged to plant large fields of a single crop to maximize profits. With improved transportation and the invention of refrigeration, produce could be shipped safely all over the world. The Industrial Revolution modernized the world. With growing resources came growing societies and economies. Between 1800 and 2000, the world’s population grew sixfold, while per capita income saw a tenfold jump (Maddison, 2003). While many people’s lives were improving, the Industrial Revolution also birthed many societal problems. There were inequalities in the system. Owners amassed vast fortunes while labourers, including young children, toiled for long hours in unsafe conditions. Workers’ rights, wage protection, and safe work environments are issues that arose during this period and remain concerns today.

Postindustrial Societies and the Information Age

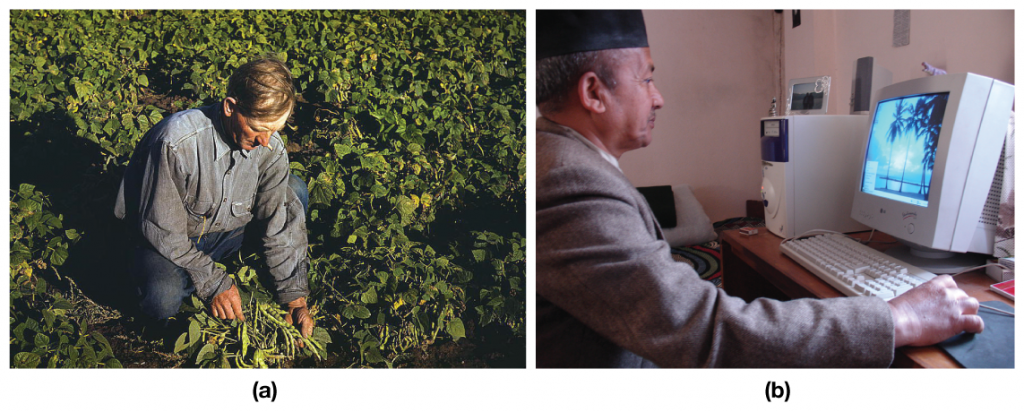

Postindustrial societies, also known as information societies, have evolved in modernized nations. One of the most valuable goods of the modern era is information. Those who have the means to produce, store, and disseminate information are leaders in this type of society. One way scholars understand the development of different types of societies (like agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial) is by examining their economies in terms of four sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Each has a different focus. The primary sector extracts and produces raw materials (like metals and crops). The secondary sector turns those raw materials into finished goods. The tertiary sector provides services: child care, health care, and money management. Finally, the quaternary sector produces ideas; these include the research that leads to new technologies, the management of information, and a society’s highest levels of education and the arts (Kenessey, 1987).

Modernization theory proposes a model of quasi-natural economic development, from undeveloped economies to advanced, to explain the difference in distribution of these sectors around the globe. In underdeveloped countries, the majority of the people work in the primary sector. As economies develop, more and more people are employed in the secondary sector. In well-developed economies, such as those in Canada, the United States, Japan, and western Europe, the majority of the workforce is employed in service industries. In Canada, for example, more than 75% of the workforce is employed in the tertiary sector (Statistics Canada, 2012). The rapid increase in computer use in all aspects of daily life is a main reason for the transition to an information economy. Fewer people are needed to work in factories because computerized robots now handle many of the tasks. Other manufacturing jobs have been outsourced to less-developed countries as a result of the developing global economy. The growth of the internet has created industries that exist almost entirely online. Within industries, technology continues to change how goods are produced. For instance, the music and film industries used to produce physical products like CDs and DVDs for distribution. Now those goods are increasingly produced digitally and streamed or downloaded at a much lower physical manufacturing cost. Information and the wherewithal to use it creatively become commodities in a postindustrial economy.

Capitalism

Scholars do not always agree on a single definition of capitalism. For our purposes, we will define capitalism as an economic system characterized by private ownership of property or capital (as opposed to state ownership), sale of commodities on the open market, the purchase of labour for wages, and the impetus to generate profit and thereby accumulate wealth. This is the type of economy in place in Canada today. Under capitalism, people invest capital (money or property invested in a business venture) in a business to produce a product or service that can be sold in a market to consumers. The investors in the company are generally entitled to a share of any profit made on sales after the costs of production and distribution are taken out. These investors often reinvest their profits to improve and expand the business or acquire new ones. To illustrate how this works, consider this example. Sarah, Antonio, and Chris each invest $250,000 into a start-up company offering an innovative baby product. When the company nets $1 million in profits its first year, a portion of that profit goes back to Sarah, Antonio, and Chris as a return on their investment. Sarah reinvests with the same company to fund the development of a second product line, Antonio uses his return to help another start-up in the technology sector, and Chris buys a small yacht for vacations. The goal for all parties is to maximize profits.

To provide their product or service, owners hire workers, to whom they pay wages. The cost of raw materials, the retail price they charge consumers, and the amount they pay in wages are determined through the law of supply and demand and by competition. This leads to the dynamic qualities of capitalism, including its instability and tendency toward crisis. When demand exceeds supply, prices tend to rise. When supply exceeds demand, prices tend to fall. When multiple businesses market similar products and services to the same buyers, there is competition. Competition can be good for consumers because it can lead to lower prices and higher quality as businesses try to get consumers to buy from them rather than from their competitors. However, competition also leads to key problems like the general tendency for a falling rate of profit, periodic crises of investment, and stock market crashes where billions of dollars of economic value can disappear overnight.

Wages tend to be set in a similar way. People who have talents, skills, education, or training that is in short supply and is needed by businesses tend to earn more than people without comparable skills. Competition in the workforce helps determine how much people will be paid. In times when many people are unemployed and jobs are scarce, people are often willing to accept less than they would when their services are in high demand. In this scenario, businesses are able to maintain or increase profits by obliging workers to accept reduced wages. When fewer people are working or people are working for lower wages, the amount of money circulating in the economy decreases, reducing the demand for commodities and services and creating a vicious cycle of economic recession or depression. To sum up, capitalism is defined by a unique set of features that distinguish it from previous economic systems such as feudalism or agrarianism, or contemporary systems such as socialism or communism:

- The means of production (i.e., productive property or capital) are privately owned and controlled.

- Labour power is purchased from workers by capitalists for a wage or salary.

- The goal of production is to make a profit from selling commodities in a competitive free market.

- Profit from the sale of commodities is appropriated by the owners of capital. Part of this profit is reinvested as capital in the business enterprise in order to expand its profitability.

- The competitive accumulation of capital and profit leads to capitalism’s dynamic qualities: constant expansion of markets, globalization of investment, growth and centralization of capital, boom and bust cycles, economic crises, class conflict, etc.

Capitalism in Practice

As capitalists began to dominate the economies of many countries during the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of businesses and their tremendous profitability gave some owners the capital they needed to create enormous corporations that could monopolize an entire industry. Many companies controlled all aspects of the production cycle for their industry, from the raw materials to the production to the stores in which they were sold. These companies were able to use their wealth to buy out or stifle any competition. In Canada, the predatory tactics used by these large monopolies caused the government to take action. In 1889, the government passed the Act for the Prevention and Suppression of Combinations Formed in the Restraint of Trade (precursor to the contemporary Competition Act of 1985), a law designed to break up monopolies and regulate how key industries — such as transportation, steel production, and oil and gas exploration and refining — could conduct business.

Canada is considered a capitalist country. However, the Canadian government has a great deal of influence on private companies through the laws it passes and the regulations enforced by government agencies. Through taxes, regulations on wages, guidelines to protect worker safety and the environment, plus financial rules for banks and investment firms, the government exerts a certain amount of control over how all companies do business. Provincial and federal governments also own, operate, or control large parts of certain industries, such as the post office, schools, hospitals, highways and railroads, and water, sewer, and power utilities. From the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s to the development of the Alberta tar sands in the 1960s and 1970s, the Canadian government has played a substantial interventionist role in investing, providing incentives, and assuming ownership in the economy. Debate over the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy remains an issue of contention today. Neoliberal economists and corporate-funded think tanks like the Fraser Institute criticize such involvements, arguing that they lead to economic inefficiency and distortion in free market processes of supply and demand. Others believe intervention is necessary to protect the rights of workers and the well-being of the general population.

Socialism

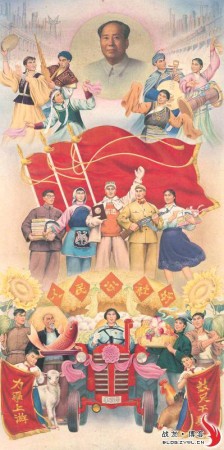

Socialism is an economic system in which there is government ownership (often referred to as “state run”) of goods and their production, with an impetus to share work and wealth equally among the members of a society. Under socialism, everything that people produce, including services, is considered a social product. Everyone who contributes to the production of a good or to providing a service is entitled to a share in any benefits that come from its sale or use. To make sure all members of society get their fair share, government must be able to control property, production, and distribution. The focus in socialism is on benefiting society, whereas capitalism seeks to benefit the individual. Socialists claim that a capitalistic economy leads to inequality, with unfair distribution of wealth and individuals who use their power at the expense of society. Socialism strives, ideally, to control the economy to avoid the problems and instabilities inherent in capitalism. Within socialism, there are diverging views on the extent to which the economy should be controlled. The communist systems of the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China under Chairman Mao Tse Tung were organized so that all but the most personal items were public property. Contemporary democratic socialism is based on the socialization or government control of essential services such as health care, education, and utilities (electrical power, telecommunications, and sewage). This is essentially a mixed economy based on a free market system and with substantial portions of the economy under private control. Farms, small shops, and businesses are privately owned, while the state might own large businesses in key sectors like energy extraction and transportation. The central component of democratic socialism, however, is the redistribution of wealth and the universal provision of services like child care, health care, and unemployment insurance through a progressive tax system.

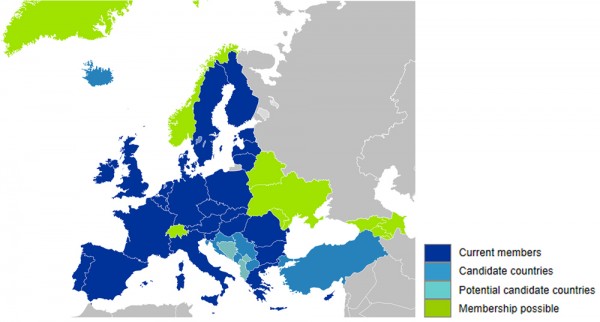

The other area on which socialists disagree is on what level society should exert its control. In communist countries like the former Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, and North Korea, the national government exerts control over the economy centrally. They had the power to tell all businesses what to produce, how much to produce, and what to charge for it. Other socialists believe control should be decentralized so it can be exerted by those most affected by the industries being controlled. An example of this would be a town collectively owning and managing the businesses on which its populace depends. Because of challenges in their economies, several of these communist countries have moved from central planning to letting market forces help determine many production and pricing decisions. Market socialism describes a subtype of socialism that adopts certain traits of capitalism, like allowing limited private ownership or consulting market demands. This could involve situations like profits generated by a company going directly to the employees of the company or being used as public funds (Gregory and Stuart, 2003). Many eastern European and some South American countries have mixed economies. Key industries are nationalized and directly controlled by the government; however, most businesses are privately owned and regulated by the government.

State intervention in the economy has been a central component to the Canadian system since the founding of the country. Democratic socialist movements became prominent in Canadian politics in the 1920s. The efforts of the western agrarian movements, the labour union movement, and the social democratic parties like the CCF (the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) and its successor, the NDP (New Democratic Party), were instrumental in implementing many of the democratic socialist features of contemporary Canada such as universal health care, old age pensions, employment insurance, and welfare.

Socialism in Practice

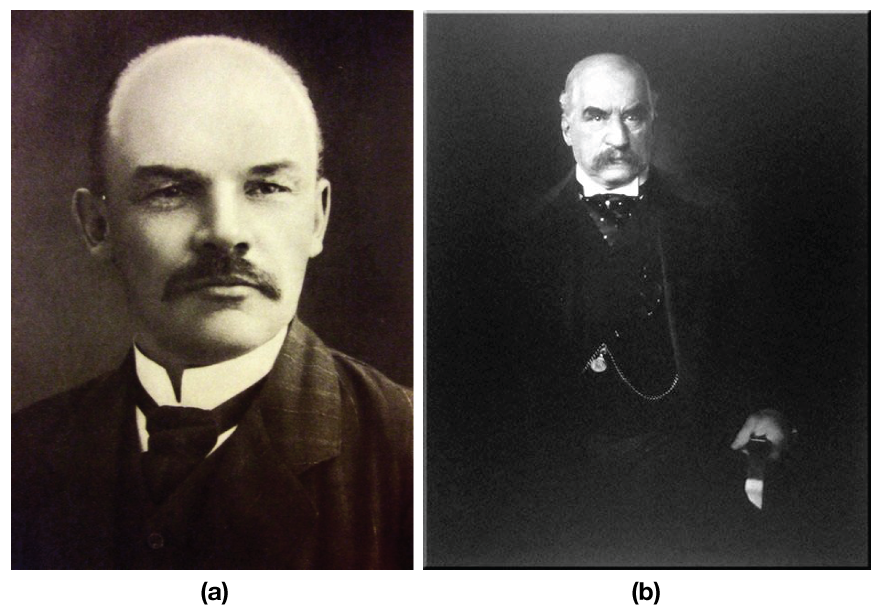

As with capitalism, the basic ideas behind socialism go far back in history. Plato, in ancient Greece, suggested a republic in which people shared their material goods. Early Christian communities believed in common ownership, as did the systems of monasteries set up by various religious orders. Many of the leaders of the French Revolution called for the abolition of all private property, not just the estates of the aristocracy they had overthrown. Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, imagined a society with little private property and mandatory labour on a communal farm. Most experimental utopian communities had the abolition of private property as a founding principle. Modern socialism really began as a reaction to the excesses of uncontrolled industrial capitalism in the 1800s and 1900s. The enormous wealth and lavish lifestyles enjoyed by owners contrasted sharply with the miserable conditions of the workers. Some of the first great sociological thinkers studied the rise of socialism. Max Weber admired some aspects of socialism, especially its rationalism and how it could help social reform, but noted that social revolution would not resolve the issues of bureaucratic control and the “iron cage of future bondage” (Greisman and Ritzer, 1981).

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809−1865) was an early anarchist who thought socialism could be used to create utopian communities. In his 1840 book, What Is Property?, he famously stated that “property is theft” (Proudhon, 1840). By this he meant that if an owner did not work to produce or earn the property or profit, then the owner was stealing it from those who did. Proudhon believed economies could work using a principle called mutualism, under which individuals and cooperative groups would exchange products with one another on the basis of mutually satisfactory contracts (Proudhon, 1840).

By far the most important influential thinker on socialism was Karl Marx (Marx and Engels, 1848). Through his own writings and those with his collaborator, industrialist Friedrich Engels, Marx used a materialist analysis to show that throughout history, the resolution of class struggles caused changes in economies. Materialist analyses focus on changes in the economic mode of production to explain the nature and transformation of the social order. Marx saw the history of class conflict developing dialectically from slave and owner, to serf and lord, to journeyman and master, to worker and owner. The resolution of one conflict was precipitated by the emergence of another. In the final epoch of class conflict, Marx argued that the development of capitalism would lead to the creation of a level of technology and economic organization sufficient to meet the needs of everyone in society equally. Scarcity, poverty, and the unequal distribution of resources were the increasingly anachronistic products of the institution of private property. However, capitalism also created the material conditions under which the working class, brought together en masse in factories and other workplaces, would recognize their common interests in ending class exploitation (i.e., they would attain “class consciousness”). Once private property was socialized through the revolution of the working classes, Marx argued that not only would the exploitive relationships of capitalism come to an end, but classes and class conflict themselves would disappear.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Obama and Socialism: A Few Definitions

In the 2008 U.S. presidential election, the Republican Party latched onto what is often considered a dirty word to describe then-Senator Barack Obama’s politics: socialist. It may have been because the president was campaigning by telling workers it’s good for everybody when wealth gets spread around. But whatever the reason, the label became a weapon of choice for Republicans during and after the campaign. In 2012, Republican presidential contender Rick Perry continued this battle cry. A New York Times article quotes him as telling a group of Republicans in Texas that President Obama is “hell bent on taking America towards a socialist country” (Wheaton, 2011). Meanwhile, during the first few years of his presidency, Obama worked to create universal health care coverage and pushed forth a partial takeover of the nation’s failing automotive industry. So does this make him a socialist? What does that really mean, anyway?

There is more than one definition of socialism, but it generally refers to an economic or political theory that advocates for shared or governmental ownership and administration of production and distribution of goods. Often held up in counterpoint to capitalism, which encourages private ownership and production, socialism is not typically an all-or-nothing plan. For example, Canada, the United Kingdom, and France, as well as other European countries, have socialized medicine, meaning that medical services are run nationally to reach as many people as possible. These nations are, of course, still essentially capitalist countries with free-market economies. So is Obama a socialist because he wants universal health care? Or is the word a lightning rod for conservatives who associate it with a lack of personal freedom? By almost any measure, the answer is more the latter. A look at the politics of President Obama and Democrats in general shows that there is, compared to most other free-market countries, very little limitation on private ownership and production. What this is, instead, is an attempt to ensure that the United States, like all other core nations, has a safety net for its poorest and most vulnerable. Although it might be in Perry’s best interest to label this as socialism, a study of the term makes it clear that it is untrue. American voters are unlikely to find, whoever their choice of candidate may be, that socialism is on the agenda in the United States.

Modernization Theory and Convergence Theory

We have seen how the economies of some capitalist countries such as Canada have features that are very similar to socialism. Some industries, particularly utilities, are either owned by the government or controlled through regulations. Public programs such as welfare, Medicare, and Social Security exist to provide public funds for private needs. We have also seen how several large communist (or formerly communist) countries such as Russia, China, and Vietnam have moved from state-controlled socialism with central planning to market socialism, which allows market forces to dictate prices and wages, and for some business to be privately owned. In many formerly communist countries, these changes have led to economic growth compared to the stagnation they experienced under communism (Fidrmuc, 2002).

Modernization theory proposes that there are natural stages of economic development that all societies go through from undeveloped to advanced. Implied in this theory is a normative model that takes the wealthy economies of the Northern and Western world as being “advanced” and then compares other economies to them. One form of modernization theory is convergence theory. In studying the economies of developing countries to see if they go through the same stages as previously developed nations did, sociologists have observed a pattern they call convergence. This describes the theory that societies move toward similarity over time as their economies develop. Convergence theory explains that as a country’s economy grows, its societal organization changes to become more like that of an industrialized society. Rather than staying in one job for a lifetime, people begin to move from job to job as conditions improve and opportunities arise. This means the workforce needs continual training and retraining. Workers move from rural areas to cities as they become centres of economic activity, and the government takes a larger role in providing expanded public services (Kerr et al., 1960). Supporters of the theory point to Germany, France, and Japan — countries that rapidly rebuilt their economies after World War II. They point out how, in the 1960s and 1970s, East Asian countries like Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan converged with countries with developed economies. They are now considered developed countries themselves.

The theory is also known as the catch-up effect because the economies of poor countries that have capital invested in them will generally grow faster than countries that are already wealthy. This allows the income of poorer countries to “catch up” under the right conditions (“Catch-up Effect,” 2011). To experience this rapid growth, the economies of developing countries must to be able to attract inexpensive capital to invest in new businesses and to improve traditionally low productivity. They need access to new, international markets for buying the goods. If these characteristics are not in place, then their economies cannot catch up. This is why the economies of some countries are diverging rather than converging (Abramovitz, 1986). Another key characteristic of economic growth regards the implementation of technology. A developing country can bypass some steps of implementing technology that other nations faced earlier. Television and telephone systems are a good example. While developed countries spent significant time and money establishing elaborate system infrastructures based on metal wires or fibre-optic cables, developing countries today can go directly to cell phone and satellite transmission with much less investment. Another factor affects convergence concerning social structure. Early in their development, countries such as Brazil and Cuba had economies based on cash crops (coffee or sugarcane, for instance) grown on large plantations by unskilled workers. The elite ran the plantations and the government, with little interest in training and educating the populace for other endeavours. This retarded economic growth until the power of the wealthy plantation owners was challenged (Sokoloff and Engerman, 2000). Improved economies generally lead to wider social improvement. Society benefits from improved educational systems, allowing people more time to devote to learning and leisure.

Convergence theory and modernization theory are often criticized, however, by those who point out that the widely varying degrees of development observed globally have less to do with natural stages of development and more to do with relations of economic exploitation and geopolitical power, especially those structured by the legacy of the periods of European colonization and American imperialism. The notion of economic development itself, which came into widespread usage only after the geopolitical realignments following World War II, is also widely disputed. It is based on the idea that the capitalist economies of the dominant Western and Northern countries represent the ideal end point of a quasi-natural incremental process. Many point out that modernization theory is better seen as a self-serving ideological framework that actually prevents observers from seeing the real diversity of economic systems and the actual modes of their operation on a global basis (see Chapter 10).

Theoretical Perspectives on the Economy

Now that we’ve developed an understanding of the history and basic components of economies, let us turn to theory. How might social scientists study these topics? What questions do they ask? What theories do they develop to add to the body of sociological knowledge?

Functionalist Perspective

Someone taking a functional perspective will most likely view work and the economy as a well-oiled machine, designed for maximum efficiency. The Davis-Moore thesis, for example, suggests that some social stratification is a social necessity. The need for certain highly skilled positions combined with the relative difficulty of the occupation and the length of time it takes to qualify will result in a higher reward for that job, providing a financial motivation to engage in more education and a more difficult profession (Davis and Moore, 1945). This theory can be used to explain the prestige and salaries that go to those with doctorates or medical degrees. Like any theory, this is subject to criticism. For example, the thesis fails to take into account the many people who spend years on their education only to pursue work at a lower-paying position in a nonprofit organization, or who teach high school after pursuing a PhD. It also fails to acknowledge the effect of life changes and social networks on individual opportunities. The underlying notion that jobs and rewards are allocated on the basis of merit (i.e., a meritocracy) is belied by data that show that both class and gender play significant roles in structuring inequality (see Chapter 9).

The functionalist perspective would assume that the continued “health” of the economy is vital to the functioning of the society, as it ensures the systematic distribution of goods and services. For example, we need food to travel from farms (high-functioning and efficient agricultural systems) via roads (safe and effective trucking and rail routes) to urban centres (high-density areas where workers can gather). However, sometimes a dysfunction — a function with the potential to disrupt social institutions or organization (Merton, 1968) — in the economy occurs, usually because some institutions fail to adapt quickly enough to changing social conditions. This lesson has been driven home recently with the financial crisis of 2008 and the bursting of the housing bubble. Due to irresponsible (i.e., dysfunctional) lending practices and an underregulated financial market, we are currently living with the after-effects of this major dysfunction.

From the functionalist view, this crisis might be regarded as an element in the cyclical nature of the internal self-regulating system of the free market economy. In functionalism, systems are said to adapt to external contingencies. Markets produce goods as they are supposed to, but eventually the market is saturated and the supply of goods exceeds the demands. Typically the market goes through phases of surplus, or excess, inflation, where the money in your pocket today buys less than it did yesterday, and recession, which occurs when there are two or more consecutive quarters of economic decline. The functionalist would say to let market forces fluctuate in a cycle through these stages. In reality, to control the risk of an economic depression (a sustained recession across several economic sectors), the Canadian government will often adjust interest rates to encourage more spending. In short, letting the natural cycle fluctuate is not a gamble most governments are willing to take.

Critical Sociology

For a conflict perspective theorist, the economy is not a source of stability for society. Instead, the economy reflects and reproduces economic inequality, particularly in a capitalist marketplace. A dominant critical perspective on the economy is the classical Marxist approach, which views the underlying dynamic of capitalism as defined by class struggle. The bourgeoisie (ruling class) accumulate wealth and power by exploiting the proletariat (workers), and regulating those who cannot work (the aged, the infirm) into the great mass of unemployed (Marx and Engels, 1848). From the symbolic (though probably made up) statement of Marie Antoinette, who purportedly said “Let them eat cake” when told that the peasants were starving, to the Occupy Wall Street movement, the sense of inequity is almost unchanged. Both the people fighting in the French Revolution and those blogging from Zuccotti Park in New York believe the same thing: wealth is concentrated in the hands of those who do not deserve it. As of 2012, 20% of Canadians owned 70% of Canadian wealth. The wealthiest 86 Canadians had amassed the same amount of wealth as the poorest 11.4 million combined (Macdonald, 2014). While the inequality might not be as extreme as in pre-revolutionary France, it is enough to make many believe that Canada is not the meritocracy it seems to be.

Symbolic Interactionist Perspective

Those working in the symbolic interaction perspective take a microanalytical view of society, focusing on the way reality is socially constructed through day-to-day interaction and how society is composed of people communicating based on a shared understanding of symbols. One important symbolic interactionist concept related to work and the economy is career inheritance. This concept means simply that children tend to enter the same or similar occupation as their parents, a correlation that has been demonstrated in research studies (Antony, 1998). For example, the children of police officers learn the norms and values that will help them succeed in law enforcement, and since they have a model career path to follow, they may find law enforcement even more attractive. Related to career inheritance is career socialization, learning the norms and values of a particular job. A symbolic interactionist might also study what contributes to job satisfaction. Melving Kohn and his fellow researchers (1990) determined that workers were most likely to be happy when they believed they controlled some part of their work, when they felt they were part of the decision-making processes associated with their work, when they have freedom from surveillance, and when they felt integral to the outcome of their work. Sunyal, Sunyal, and Yasin (2011) found that a greater sense of vulnerability to stress, the more stress experienced by a worker, and a greater amount of perceived risk consistently predicted a lower worker job satisfaction.

18.2. Work in Canada

Common wisdom states that if you study hard, develop good work habits, and graduate from high school or, even better, university, then you’ll have the opportunity to land a good job. That has long been seen as the key to a successful life. And although the reality has always been more complex than suggested by the myth, the worldwide recession that began in 2008 has made it harder than ever to play by the rules and win the game. The data are grim: for example, in the United States, from December 2007 through March 2010, 8.2 million workers lost their jobs, and the unemployment rate grew to almost 10% nationally, with some states showing much higher rates (Autor, 2010). Times are very challenging for those in the workforce. For those looking to finish their schooling, often with enormous student-debt burdens, it is not just challenging — it is terrifying. So where did all the jobs go? Will any of them be coming back, and if not, what new ones will there be? How do you find and keep a good job now? These are the kinds of questions people are currently asking about the job market in Canada.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World?

Real Money, Virtual Worlds

If you are not one of the tens of millions of gamers who enjoy World of Warcraft or other online virtual world games, you might not even know what MMORPG stands for. But if you made a living playing MMORPGs, as a growing number of enterprising gamers do, then massive multiplayer online role-playing games might matter a bit more. According to an article in Forbes magazine, the online world of gaming has been yielding very real profits for entrepreneurs who are able to buy, sell, and manage online real estate, currency, and more for cash (Holland and Ewalt, 2006). If it seems strange that people would pay real money for imaginary goods, consider that for serious gamers the online world is of equal importance to the real one. These entrepreneurs can sell items because the gaming sites have introduced scarcity into the virtual worlds. The game makers have realized that MMORPGs lack tension without a level of scarcity for needed resources or highly desired items. In other words, if anyone can have a palace or a vault full of wealth, then what’s the fun?

So how does it work? One of the easiest ways to make such a living is called gold farming, which involves hours of repetitive and boring play, hunting and shooting animals like dragons that carry a lot of wealth. This virtual wealth can be sold on eBay for real money: a timesaver for players who do not want to waste their playing time on boring pursuits. Players in parts of Asia engage in gold farming, playing eight hours a day or more, to sell their gold to players in western Europe or North America. From virtual prostitutes to power levellers (people who play the game logged in as you so your characters get the wealth and power), to architects, merchants, and even beggars, online players can offer to sell any service or product that others want to buy. Whether buying a magic carpet in World of Warcraft or a stainless-steel kitchen appliance in Second Life, gamers have the same desire to acquire as the rest of us — never mind that their items are virtual. Once a gamer creates the code for an item, she can sell it again and again, for real money. Finally, you can also sell yourself. According to Forbes, a University of Virginia computer science student sold his World of Warcraft character on eBay for $1,200, due to the high levels of powers and skills it had gained (Holland and Ewalt, 2006). So should you quit your day job to make a killing in online games? Probably not. Those who work hard might eke out a decent living, but for most people, grabbing up land that does not really exist or selling your body in animated action scenes is probably not the best opportunity. Still, for some, it offers the ultimate in work-from-home flexibility, even if that home is a mountain cave in a virtual world.

Polarization in the Workforce

The mix of jobs available in Canada began changing many years before the recession struck. Geography, race, gender, and other factors have always played a role in the reality of success. More recently, the increased outsourcing (or contracting a job or set of jobs to an outside source) of manufacturing jobs to developing nations has greatly diminished the number of high-paying, often unionized, blue-collar positions available. A similar problem has arisen in the white-collar sector, with many low-level clerical and support positions also being outsourced, as evidenced by the international technical-support call centres in Mumbai, India. The number of supervisory and managerial positions has been reduced as companies streamline their command structures and industries continue to consolidate through mergers. Even highly educated skilled workers such as computer programmers have seen their jobs vanish overseas.

The automation (replacing workers with technology) of the workplace is another cause of the changes in the job market. Computers can be programmed to do many routine tasks faster and less expensively than people who used to do such tasks. Jobs like bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive tasks on production assembly lines all lend themselves to automation. Think about the newer automated toll passes we can install in our cars. Toll collectors are just one of the many endangered jobs that will soon cease to exist. Despite all this, the job market is actually growing in some areas, but in a very polarized fashion. Polarization means that a gap has developed in the job market, with most employment opportunities at the lowest and highest levels and few jobs for those with mid-level skills and education. At one end, there has been strong demand for low-skilled, low-paying jobs in industries like food service and retail. On the other end, some research shows that in certain fields there has been a steadily increasing demand for highly skilled and educated professionals, technologists, and managers. These high-skilled positions also tend to be highly paid (Autor, 2010).

The fact that some positions are highly paid while others are not is an example of the dual labour market structure, a division of the economy into sectors with different levels of pay. The primary labour market consists of high-paying jobs in the public sector, manufacturing, telecommunications, biotechnology, and other similar sectors that require high levels of capital investment (or other restrictions) that limit the number of businesses able to enter the sector. The costs of labour are considered marginal in comparison to the total capital investment required. Jobs in the sector usually offer good benefits, security, prospects for advancement, and comparatively higher levels of unionization. The secondary labour market consists of jobs in more competitive sectors of the economy like service industries, restaurants, and commercial enterprises, where the cost of entry for businesses is relatively low. Jobs in the secondary labour market are usually poorly paid, offer few if any benefits, and have little job security, poor prospects for advancement, and minimal unionization. Wages paid to employees make up a significant portion of the cost of products or services offered to consumers, and because of the high level of competition, businesses are obliged to keep the cost of labour to a minimum to remain competitive.

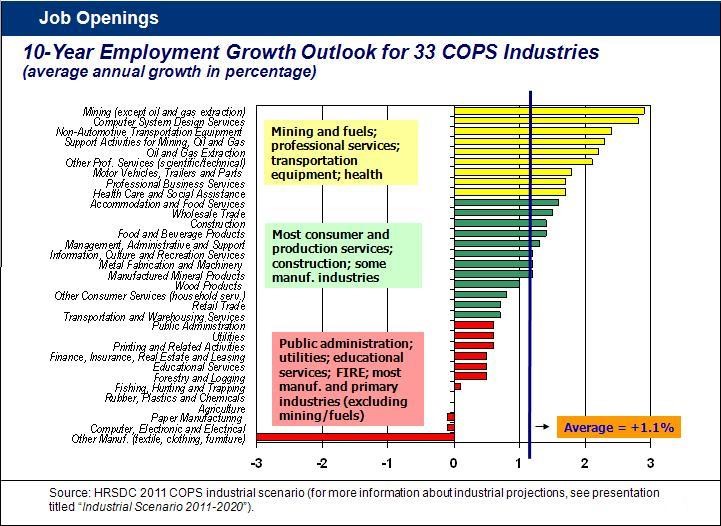

Hard work does not guarantee success in the dual labour market economy, because social capital — the accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success — in the form of connections or higher education are often required to access the high-paying jobs. Increasingly, we are realizing intelligence and hard work are not enough. If you lack knowledge of how to leverage the right names, connections, and players, you are unlikely to experience upward mobility. Particularly in the knowledge economy, which generates a new dual labour market between jobs that require high levels of education (scientists, programmers, designers, etc.) and support jobs (secretarial, data entry, technicians, etc.), social capital in the form of formal education is a condition for accessing quality jobs. The division between those who are able to access, create, utilize, and disseminate knowledge and those who cannot is often referred to as the knowledge divide. With so many jobs being outsourced or eliminated by automation, what kinds of jobs is there a demand for in Canada? While manufacturing jobs are in decline and fishing and agriculture are static, several job markets are expanding. These include resource extraction, computer and information services, professional business services, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services. Figure 18.11, from Employment and Social Development Canada, illustrates areas of projected growth.

Professional and related jobs, which include any number of positions, typically require significant education and training and tend to be lucrative career choices. Service jobs, according to Employment and Social Development Canada, can include everything from consumer service jobs such as scooping ice cream, to producer service jobs that contract out administrative or technical support, to government service jobs including teachers and bureaucrats (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011b). There is a wide variety of training needed, and therefore an equally large wage potential discrepancy. One of the largest areas of growth by industry, rather than by occupational group (as seen above), is in the health field (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011a). This growth is across occupations, from associate-level nurse’s aides to management-level assisted-living staff. As baby boomers age, they are living longer than any generation before, and the growth of this population segment requires an increase in capacity throughout our country’s elder care system, from home health care nursing to geriatric nutrition. Notably, jobs in manufacturing are in decline. This is an area where those with less education traditionally could be assured of finding steady, if low-wage, work. With these jobs disappearing, more and more workers will find themselves untrained for the types of employment that are available. Another projected trend in employment relates to the level of education and training required to gain and keep a job.

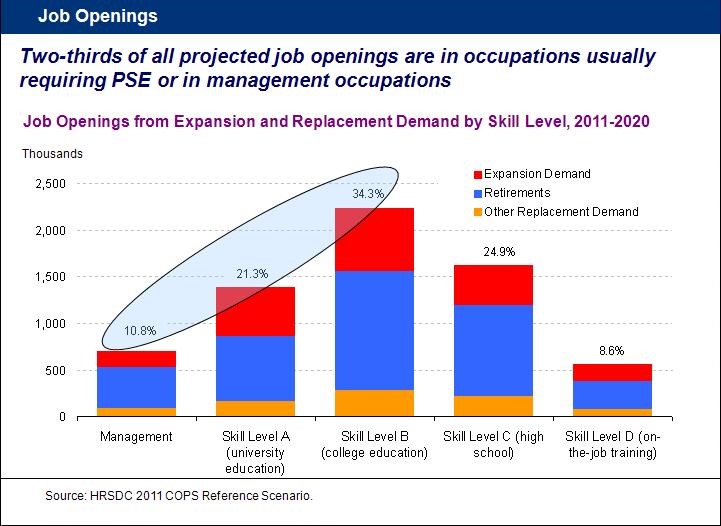

As Figure 18.12 shows, growth rates are higher for those with more education. It is estimated that between 2011 and 2020, there will be 6.5 million new job openings due to economic growth or retirement, two-thirds of which will be in occupations that require post-secondary education (“PSE” in the chart) or in management positions (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011a). 70% of new jobs created through economic growth are projected to be in management or occupations that require post-secondary education. Those with a university degree may expect job growth of 21.3%, and those with a college degree or apprenticeship 34.3%. At the other end of the spectrum, jobs that require a high school diploma or equivalent are projected to grow at only 24.9%, while jobs that require less than a high school diploma will grow at 8.6%. Quite simply, without a degree, it will be more difficult to find a job. It is worth noting that these projections are based on overall growth across all occupation categories, so obviously there will be variations within different occupational areas. Seven out of the ten occupations with the highest proportion of job openings are in management and the health sector. However, once again, those who are the least educated will be the ones least able to fulfill the Canadian dream.

Women in the Workforce

In the past, rising education levels in Canada were able to keep pace with the rise in the number of education-dependent jobs. Since the late 1970s, men have been enrolling in university at a lower rate than women, and graduating at a rate of almost 10% less (Wang and Parker, 2011). In 2008, 62% of undergraduate degrees and 54% of graduate degrees were granted to women (Drolet, 2011). The lack of male candidates reaching the education levels needed for skilled positions has opened opportunities for women and immigrants. Women have been entering the workforce in ever-increasing numbers for several decades. Their increasingly higher levels of education attainment than men has resulted in many women being better positioned to obtain high-paying, high-skill jobs. Between 1991 and 2011, the percentage of employed women between the ages of 25 and 34 with a university degree increased from 19% to 40%, whereas among employed men aged 25 to 34 the percentage increased from 17% to 27%.

It is interesting to note however that at least 20% of all women with a university degree were still employed in the same three occupations as they were in 1991: registered nurses, elementary school and kindergarten teachers, and secondary school teachers. The top three occupations for university-educated men (11% of this group) were computer programmers and interactive media developers, financial auditors and accountants, and secondary school teachers (Uppal and LaRochelle-Côté, 2014). While women are getting more and better jobs and their wages are rising more quickly than men’s wages are, Statistics Canada data show that they are still earning only 76% of what men are for the same positions. However when the wages of young women aged 25 to 29 are compared to young men in the same age cohort, the women now earn 90% of young men’s hourly wage (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Immigration and the Workforce

Simply put, people will move from where there are few or no jobs to places where there are jobs, unless something prevents them from doing so. The process of moving to a country is called immigration. Canada has long been a destination for workers of all skill levels. While the rate decreased somewhat during the economic slowdown of 2008, immigrants, both legal and illegal, continue to be a major part of the Canadian workforce. In 2006, before the recession arrived, immigrants made up 19.9% of the workforce, up from 19 percent in 1996 (Kustec, 2012). The economic downturn affected them disproportionately. In 2008, employment rates were at the peak for both native-born Canadians (84.1%) and immigrants (77.4%). In 2009, these figures dropped to 82.2% and 74.9% respectively, meaning that the gap in employment rates increased to 7.3 percentage points from 6.7. The gap was greater between native-born and very recent immigrants (18.6 percentage points in 2009, compared with a gap of 17.5 points in 2008) (Yssaad, 2012). Interestingly, in the United States, this trend was reversed. The unemployment rate decreased for immigrant workers and increased for native workers (Kochhar, 2010). This no doubt did not help to reduce tensions in that country about levels of immigration, particularly illegal immigration.

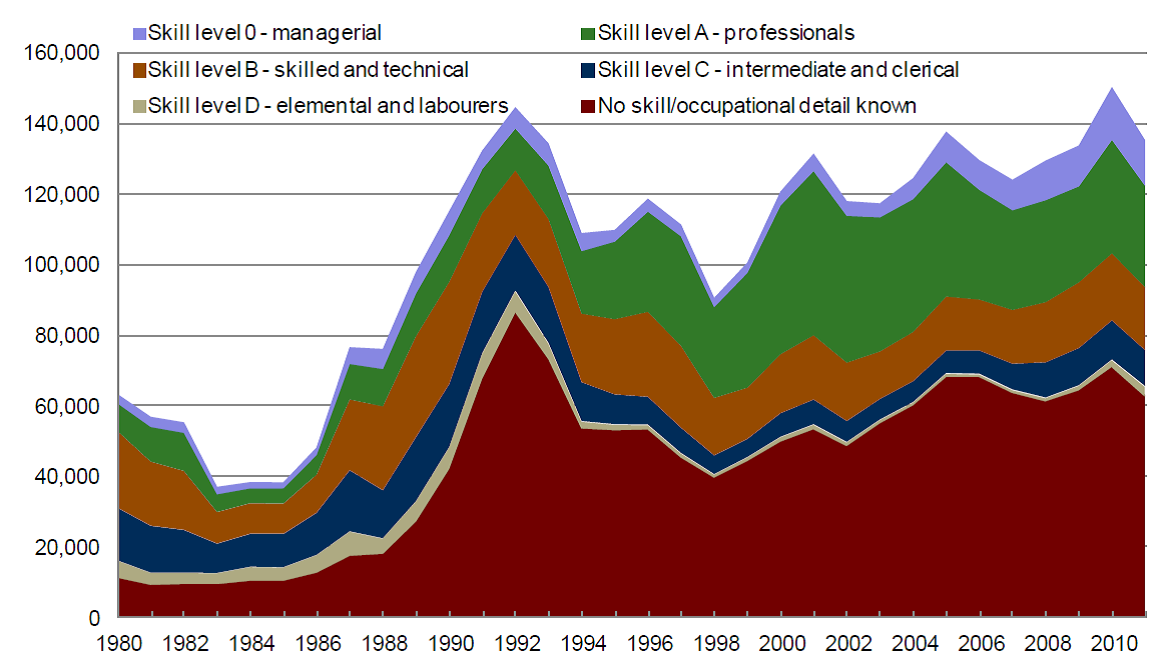

Recent political debate about the Temporary Foreign Worker Program has been fuelled by conversations about low-skilled service industry jobs being taken by low-earning foreign workers (Mas, 2014). It should be emphasized that a substantial portion of working-age immigrants (i.e., not temporary workers) landing in Canada are highly educated and highly skilled (Figure 18.13). They play a significant role in filling skilled positions that open up through both job creation and retirement. About half of the landed immigrants identify an occupational skill, 80 to 90% of which fall within the higher skill level classifications. Of the other 50% of landed immigrants who intend to work but do not indicate a specific occupational skill, most have recently completed school and are new to the labour market, or have landed under the family class or as refugees — classes which are not coded by occupation (Kustec, 2012).

Poverty in Canada

When people lose their jobs during a recession or in a changing job market, it takes longer to find a new one, if they can find one at all. If they do, it is often at a much lower wage or not full time. This can force people into poverty. In Canada, we tend to have what is called relative poverty, defined as being unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country. This must be contrasted with the absolute poverty that can be found in underdeveloped countries, defined as being barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities such as food (Byrns, 2011). We cannot even rely on unemployment statistics to provide a clear picture of total unemployment in Canada. First, unemployment statistics do not take into account underemployment, a state in which people accept lower-paying, lower-status jobs than their education and experience qualifies them to perform. Second, unemployment statistics only count those:

- who are actively looking for work

- who have not earned income from a job in the past four weeks

- who are ready, willing, and able to work

The unemployment statistics provided by Statistics Canada are rarely accurate, because many of the unemployed become discouraged and stop looking for work. Not only that, but these statistics undercount the youngest and oldest workers, the chronically unemployed (e.g., homeless), and seasonal and migrant workers.

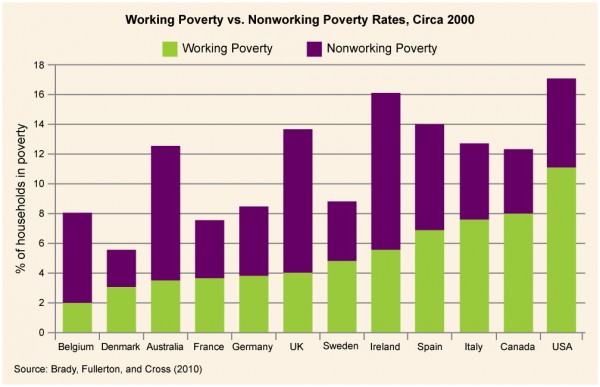

A certain amount of unemployment is a direct result of the relative inflexibility of the labour market, considered structural unemployment, which describes when there is a societal level of disjuncture between people seeking jobs and the available jobs. This mismatch can be geographic (they are hiring in Alberta, but the highest rates of unemployment are in Newfoundland and Labrador), technological (skilled workers are replaced by machines, as in the auto industry), or can result from any sudden change in the types of jobs people are seeking versus the types of companies that are hiring. Because of the high standard of living in Canada, many people are working at full-time jobs but are still poor by the standards of relative poverty. They are the working poor. Canada has a higher percentage of working poor than many other developed countries (Brady, Fullerton, and Cross, 2010). In terms of employment, Statistics Canada defines the working poor as those who worked for pay at least for at least 910 hours during the year, and yet remain below the poverty line according to the Market Basket Measure (i.e., they lack the disposable income to purchase a specified “basket” of basic goods and services). Many of the facts about the working poor are as expected: those who work only part time are more likely to be classified as working poor than those with full-time employment; higher levels of education lead to less likelihood of being among the working poor; and those with children under 18 are four times more likely than those without children to fall into this category. In 2011, 6.4% of Canadians of all ages lived in households classified as working poor (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2011).

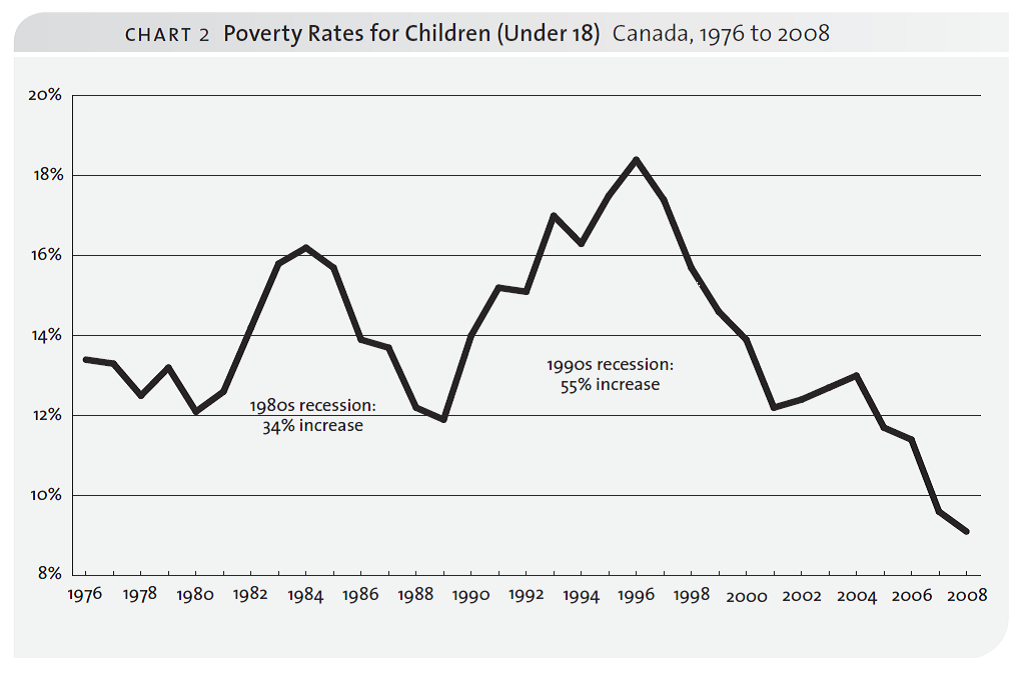

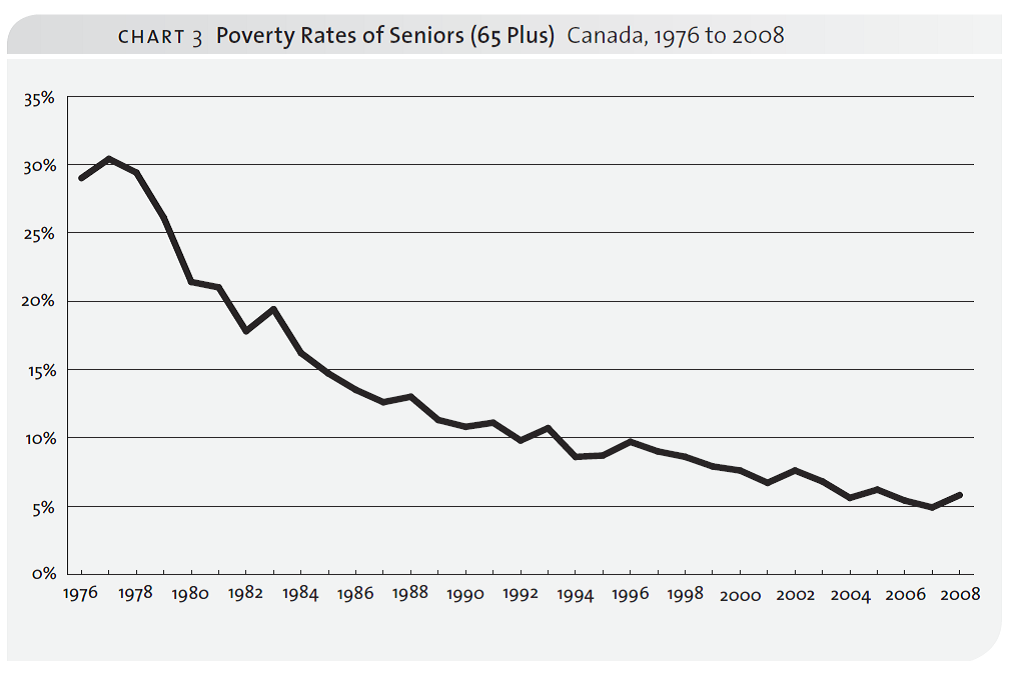

Most developed countries such as Canada protect their citizens from absolute poverty by providing different levels of social services such as employment insurance, welfare, health care, and so on. They may also provide job training and retraining so that people can re-enter the job market. In the past, the elderly were particularly vulnerable to falling into poverty after they stopped working; however, the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, the Old Age Security program, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement are credited with successfully reducing old age poverty. A major concern in Canada is the number of young people growing up in poverty, although these numbers have been declining as well. About 606,000 children younger than 18 lived in low-income families in 2008. The proportion of children in low-income families was 9% in 2008, half the 1996 peak of 18% (Statistics Canada, 2011). Growing up poor can cut off access to the education and services people need to move out of poverty and into stable employment. As we saw, more education was often a key to stability, and those raised in poverty are the ones least able to find well-paying work, perpetuating a cycle.

With the shift to neoliberal economic policies, there has been greater debate about how much support local, provincial, and federal governments should give to help the unemployed and underemployed. Often the issue is presented as one in which the interests of “taxpayers” are opposed to the “welfare state.” It is interesting to note that in social democratic countries like Norway, Finland, and Sweden, there is much greater acceptance of higher tax rates when these are used to provide universal health care, education, child care, and other forms of social support than there is in Canada. Nevertheless, the decisions made on these issues have a profound effect on working in Canada.

Key Terms

alienation: The condition in which an individual is isolated from their society, work, or the sense of self and common humanity.

automation: Workers being replaced by technology.

bartering: When people exchange one form of goods or services for another.

capitalism: An economic system based on private ownership of property or capital, competitive markets, wage labour, and the impetus to produce profit and accumulate private wealth.

career inheritance: When children tend to enter the same or similar occupation as their parents.

commodities: Goods produced for sale on the market.

convergence theory: A sociological theory to explain how and why societies move toward similarity over time as their economies develop.

depression: A sustained recession across several economic sectors.

dual labour market: The division of the economy into high-wage and low-wage sectors.

economy: The social institution through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed.

goods: Physical objects we find, grow, or make to meet our needs and those of others.

knowledge divide: The division between those who are able to access, create, utilize, and disseminate knowledge and those who cannot.

market socialism: A subtype of socialism that adopts certain traits of capitalism, like allowing limited private ownership or consulting market demand.

mercantilism: An economic policy based on national policies of accumulating silver and gold by controlling markets with colonies and other countries through taxes and customs charges.

modernization theory: A theory of economic development that proposes that there are natural stages of economic development that all societies go through from undeveloped to advanced.

money: An object that a society agrees to assign a value to so it can be exchanged as payment.

mutualism: A form of socialism under which individuals and cooperative groups exchange products with one another on the basis of mutually satisfactory contracts.

outsourcing: When jobs are contracted to an outside source, often in another country.

polarization: When the differences between low-end and high-end jobs becomes greater and the number of people in the middle levels decreases.

recession: When there are two or more consecutive quarters of economic decline.

services: Activities that benefit people, such as health care, education, and entertainment.

social capital: The accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success.

socialism: An economic system in which there is government ownership (often referred to as “state run”) of goods and their production, with an impetus to share work and wealth equally among the members of a society.

structural unemployment: When there is a societal level of disjuncture between people seeking jobs and the jobs that are available.

subsistence farming: When farmers grow only enough to feed themselves and their families.

underemployment: A state in which a person accepts a lower-paying, lower-status job than their education and experience qualifies them to perform.

usufruct: The distribution of resources according to need.

Section Summary

18.1. Economic Systems

Economy refers to the social institution through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed. The Agricultural Revolution led to development of the first economies that were based on trading goods. Mechanization of the manufacturing process led to the Industrial Revolution and gave rise to two major competing economic systems. Under capitalism, private owners invest their capital and that of others to produce goods and services they can sell in an open market. Prices and wages are set by supply and demand and competition. Under socialism, the means of production is commonly owned, and the economy is controlled centrally by government. Several countries’ economies exhibit a mix of both systems. Convergence theory seeks to explain the correlation between a country’s level of development and changes in its economic structure.

18.2. Work in Canada

The job market in Canada is meant to be a meritocracy that creates social stratifications based on individual achievement. Economic forces, such as outsourcing and automation, are polarizing the workforce, with most job opportunities being either low-level, low-paying manual jobs or high-level, high-paying jobs based on abstract skills. Women’s role in the workforce has increased, although they have not yet achieved full equality. Immigrants play an important role in the Canadian labour market. The changing economy has forced more people into poverty even if they are working. Welfare, old age pensions, and other social programs exist to protect people from the worst effects of poverty.

Section Quiz

18.1. Economic Systems

1. Which of these is an example of a commodity?

- Cooking

- Corn

- Teaching

- Writing

2. When did the first economies begin to develop?

- When all of the hunter-gatherers died

- When money was invented

- When people began to grow crops and domesticate animals

- When the first cities were built

3. What is the most important commodity in a postindustrial society?

- Electricity

- Money

- Information

- Computers

4. In which sector of an economy would someone working as a software developer be?

- Primary

- Secondary

- Tertiary

- Quaternary

5. Which is an economic policy based on national policies of accumulating silver and gold by controlling markets with colonies and other countries through taxes and customs charges?

- Capitalism

- Communism

- Mercantilism

- Mutualism

6. Who was the leading theorist on the development of socialism?

- Karl Marx

- Alex Inkeles

- Émile Durkheim

- Adam Smith

7. The type of socialism now carried on by Cuba is a form of ______ socialism.

- centrally planned

- market

- utopian

- zero-sum

8. Which country serves as an example of convergence?

- Singapore

- North Korea

- England

- Canada

18.2. Work in Canada

9. Which is evidence that the Canadian workforce is largely a meritocracy?

- Job opportunities are increasing for highly skilled jobs.

- Job opportunities are decreasing for mid-level jobs.

- Highly skilled jobs pay better than low-skill jobs.

- Women tend to make less than men do for the same job.

10. If someone does not earn enough money to pay for the essentials of life they are said to be _____ poor.

- absolutely

- essentially

- really

- working

11. About what percentage of the workforce in Canada are legal immigrants?

- Less than 1%

- 1%

- 20%

- 66%

Short Answer

- Explain the difference between state socialism with central planning and market socialism.

- In what ways can capitalistic and socialistic economies converge?

- Describe the impact a rapidly growing economy can have on families.

- How do you think the Canadian economy will change as we move closer to a technology-driven service economy?

- As polarization occurs in the Canadian job market, this will affect other social institutions. For example, if mid-level education does not lead to employment, we could see polarization in educational levels as well. Use the sociological imagination to consider what social institutions may be impacted, and how.

- Do you believe we have a true meritocracy in Canada? Why or why not?

Further Research

18.1. Economic Systems

Green jobs have the potential to improve not only your prospects of getting a good job, but the environment as well. Learn more about the green revolution in jobs: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/greenjobs.

18.2. Work in Canada

The role of women in the workplace is constantly changing: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11387-eng.htm.

The Employment Projections Program of Employment and Social Development Canada looks at a ten-year projection for jobs and employment. See some employment trends for the next decade: http://occupations.esdc.gc.ca/sppc-cops/w.2lc.4m.2@-eng.jsp.

Global poverty is tracked by the globalissues.org website. See recent analyses and statistics about poverty: http://www.globalissues.org/article/26/poverty-facts-and-stats.

References

18.1. Economic Systems

Abramovitz, Moses. (1986). Catching up, forging ahead and falling behind. Journal of Economic History, 46(2):385–406. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.jstor.org/pss/2122171.

Antony, James. (1998). Exploring the factors that influence men and women to form medical career aspirations. Journal of College Student Development, 39:417–426.

Bond, Eric, Sheena Gingerich, Oliver Archer-Antonsen, Liam Purcell, and Elizabeth Macklem. (2003). The industrial revolution — Innovations. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://industrialrevolution.sea.ca/innovations.html.

Bookchin, Murray. (1982). The ecology of freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Palo Alto CA: Cheshire Books.

Boxall, Michael. (2006, February 9). Just don’t call it funny money. The Tyee. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://thetyee.ca/News/2006/02/09/FunnyMoney/

Davis, Kingsley and Wilbert Moore. (1945). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10:242–249.

Diamond, J. and P. Bellwood. (2003, April 25). Farmers and their languages: The first expansions. Science, April 25: 597-603.

The Economist. (2011). Economics A-Z terms beginning with C: Catch-up Effect. The Economist.com. Retrieved February 5, 2012, from http://www.economist.com/economics-a-to-z/c#node-21529531.

Fidrmuc, Jan. (2002). Economic reform, democracy and growth during post-communist transition. [PDF] European Journal of Political Economy, 19(30):583–604. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECINEQ/Resources/fidrmuc.pdf.

Goldsborough, Reid. (2010). A case for the world’s oldest coin: Lydian Lion. World’s Oldest Coin – First Coins [Website]. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://rg.ancients.info/lion/article.html).

Gregory, Paul R. and Robert C. Stuart. (2003). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century. Boston, MA: South-Western College Publishing.

Greisman, Harvey C. and George Ritzer. (1981). Max Weber, critical theory, and the administered world. Qualitative Sociology, 4(1):34–55. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/k14085t403m33701/.

Horne, Charles F. (1915). The code of Hammurabi : Introduction. Yale University. Retrieved July 11, 2016, from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/hammenu.asp.

Kenessey, Zoltan. (1987). The primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy. The Review of Income and Wealth, 33(4):359–386.

Kerr, Clark, John T. Dunlap, Frederick H. Harbison, and Charles A. Myers. (1960). Industrialism and industrial man. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kohn, Melvin, Atsushi Naoi, Carrie Schoenbach, Carmi Schooler, and Kazimierz Slomczynski. (1990). Position in the class structure and psychological functioning in the United States, Japan, and Poland. American Journal of Sociology, 95:964–1008.

Macdonald, David. (2014, April). Outrageous fortune: Documenting Canada’s wealth gap. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2014/04/Outrageous_Fortune.pdf.

Maddison, Angus. (2003). The world economy: Historical statistics. Paris: Development Centre, OECD. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.theworldeconomy.org/.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (1998). The communist manifesto. New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1848)

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (1988). Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844 and the communist manifesto. (Translated by M. Milligan). New York: Prometheus Books. (Original work published 1844)

Mauss, Marcel. (1990). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies, London: Routledge. (Original work published 1922)

Merton, Robert. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free Press.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (2010). Property is theft! A Pierre-Joseph Proudhon anthology. Iain McKay (Ed.). Retrieved February 15, 2012, from http://anarchism.pageabode.com/pjproudhon/property-is-theft. (Original work published 1840)

Schwermer, Heidemarie. (2007). Gib und Nimm. Retrieved January 22, 2012, from http://www.heidemarieschwermer.com/.