Main Body

Chapter 13. Aging and the Elderly

Learning Objectives

13.1. Who Are the Elderly? Aging in Society

- Understand the difference between senior age groups (young-old, middle-old, and old-old).

- Describe the “greying of Canada” as the population experiences increased life expectancies.

- Examine aging as a global issue.

- Consider the biological, social, and psychological changes in aging.

- Describe the birth of the field of geriatrics.

- Examine attitudes toward death and dying and how they affect the elderly.

- Name the five stages of grief developed by Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

13.3. Challenges Facing the Elderly

- Understand the historical and current trends of poverty among elderly populations.

- Recognize ageist thinking and ageist attitudes in individuals and in institutions.

- Learn about elderly individuals’ risks of being mistreated and abused.

13.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Aging

- Compare and contrast sociological theoretical perspectives on aging.

Introduction to Aging and the Elderly

At age 52, Bridget Fisher became a first-time grandmother. She worked in human resources (HR) at a scientific research company, a job she’d held for 20 years. She had raised two children, divorced her first husband, remarried, and survived a cancer scare.

Her fast-paced job required her to travel around the country, setting up meetings and conferences. The company did not offer retirement benefits. Bridget had seen many employees put in 10, 15, or 20 years of service only to get laid off when they were considered too old. Because of laws against age discrimination, the company executives were careful to prevent any records from suggesting age as the reason for the layoffs.

Seeking to avoid the crisis she would face if she were laid off, Bridget went into action. She took advantage of the company’s policy to put its employees through college if they continued to work two years past graduation. Completing evening classes in nursing at the local technical school, she became a registered nurse after four years. She worked two more years, then quit her job in HR, and accepted a part-time nursing job at a family clinic. Her new job offered retirement benefits. Bridget no longer had to travel to work and she was able to spend more time with her family and to cultivate new hobbies.

Today, Bridget Fisher, 62, is a wife, mother of two, grandmother of three, part-time nurse, master gardener, and quilt club member. She enjoys golfing and camping with her husband and taking her terriers to the local dog park. She does not expect to retire from the workforce for five or ten more years, and though the government officially considers her a senior citizen, she doesn’t feel old. In fact, while bouncing her grandchild on her knee, Bridget tells her daughter, 38, “I never felt younger.”

Age is not merely a biological function of the number of years one has lived, or of the physiological changes the body goes through during the life course. It is also a product of the social norms and expectations that apply to each stage of life. Age represents the wealth of life experiences that shape whom we become. With medical advancements that prolong human life, old age has taken on a new meaning in societies with the means to provide high-quality medical care. However, many aspects of the aging experience also depend on social class, race, gender, and other social factors.

13.1. Who Are the Elderly? Aging in Society

Think of the movies and television shows you have watched recently. Did any of them feature older actors? What roles did they play? How were these older actors portrayed? Were they cast as main characters in a love story? Grouchy old people? How were older women portrayed? How were older men portrayed?

Many media portrayals of the elderly reflect negative cultural attitudes toward aging. In North America, society tends to glorify youth, associating it with beauty and sexuality. In comedies, the elderly are often associated with grumpiness or hostility. Rarely do the roles of older people convey the fullness of life experienced by seniors—as employees, lovers, or the myriad roles they have in real life. What values does this reflect?

One hindrance to society’s fuller understanding of aging is that people rarely understand it until they reach old age themselves. (As opposed to childhood, for instance, which we can all look back on.) Therefore, myths and assumptions about the elderly and aging are common. Many stereotypes exist surrounding the realities of being an older adult. While individuals often encounter stereotypes associated with race and gender and are thus more likely to think critically about them, many people accept age stereotypes without question (Levy et al., 2002). Each culture has a certain set of expectations and assumptions about aging, all of which are part of our socialization.

While the landmarks of maturing into adulthood are a source of pride, signs of natural aging can be cause for shame or embarrassment. Some people try to fight off the appearance of aging with cosmetic surgery. Although many seniors report that their lives are more satisfying than ever, and their self-esteem is stronger than when they were young, they are still subject to cultural attitudes that make them feel invisible and devalued.

Gerontology is a field of science that seeks to understand the process of aging and the challenges encountered as seniors grow older. Gerontologists investigate age, aging, and the aged. Gerontologists study what it is like to be an older adult in a society and the ways that aging affects members of a society. As a multidisciplinary field, gerontology includes the work of medical and biological scientists, social scientists, and even financial and economic scholars.

Social gerontology refers to a specialized field of gerontology that examines the social (and sociological) aspects of aging. Researchers focus on developing a broad understanding of the experiences of people at specific ages, such as mental and physical well-being, plus age-specific concerns such as the process of dying. Social gerontologists work as social researchers, counsellors, community organizers, and service providers for older adults. Because of their specialization, social gerontologists are in a strong position to advocate for older adults.

Scholars in these disciplines have learned that aging reflects not just the physiological process of growing older, but also our attitudes and beliefs about the aging process. You’ve likely seen online calculators that promise to determine your “real age” as opposed to your chronological age. These ads target the notion that people may feel a different age than their actual years. Some 60-year-olds feel frail and elderly, while some 80-year-olds feel sprightly.

Equally revealing is that as people grow older they define “old age” in terms of greater years than their current age (Logan, 1992). Many people want to postpone old age, regarding it as a phase that will never arrive. Some older adults even succumb to stereotyping their own age group (Rothbaum, 1983).

In North America, the experience of being elderly has changed greatly over the past century. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many U.S. households were home to multigenerational families, and the experiences and wisdom of elders was respected. They offered wisdom and support to their children and often helped raise their grandchildren (Sweetser, 1984).

Today, with most households confined to the nuclear family, attitudes toward the elderly have changed. In 2011, of the 13,320,615 private households in the country, only about 400,000 of them (3.1%) were multigenerational (Statistics Canada, 2012b). It is no longer typical for older relatives to live with their children and grandchildren.

Attitudes toward the elderly have also been affected by large societal changes that have happened over the past 100 years. Researchers believe industrialization and modernization have contributed greatly to lowering the power, influence, and prestige the elderly once held.

The elderly have both benefitted and suffered from these rapid social changes. In modern societies, a strong economy created new levels of prosperity for many people. Health care has become more widely accessible and medicine has advanced, allowing the elderly to live longer. However, older people are not as essential to the economic survival of their families and communities as they were in the past. While the average person now lives 20 years longer than they did 90 years ago (Statistics Canada, 2010), the prestige associated with age has declined.

Studying Aging Populations

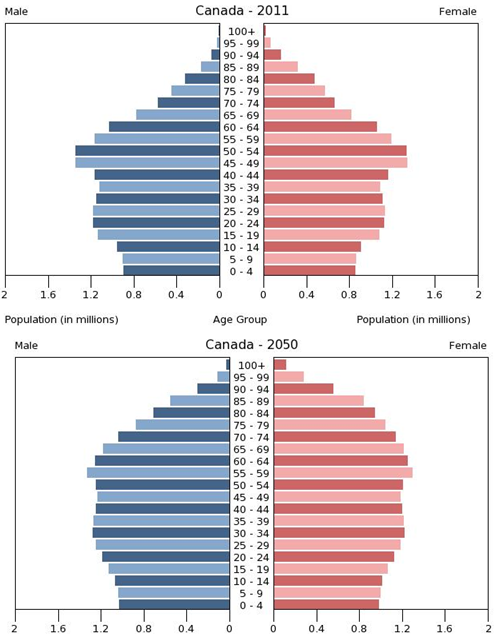

The first census in Canada was conducted in 1666 on the colony’s 3,215 inhabitants and included questions about age as well as sex, marital status, and occupation. Since the first national census in 1871, the Canadian government has been tracking age in the population every 10 years (Statistics Canada, 2013a). Age is an important factor to analyze with accompanying demographic figures, such as income and health. The population pyramid below shows projected age distribution patterns for the next several decades.

Statisticians use data to calculate the median age of a population, that is, the number that marks the halfway point in a group’s age range. In Canada, the median age is about 40 (Statistics Canada, 2013b). That means that about half of Canadians are under 40 and about half are over 40. The median age of women is higher than men, 41.1 compared to 39.4, due to the persistent higher life expectancy of women (although the gap between genders has been diminishing).

Overall the median age of Canadians has been increasing, indicating that the population as a whole is growing older. It is interesting to note, however, that the proportion of senior citizens in Canada is lower than most of the other G8 countries. In 2013, 15.3% of Canadians were over 65 while 25% of Japanese, 21% of Germans, 21% of Italians, 17% of French, and 16% of British were over 65. Only the United States (14%) and Russia (13%) had lower proportions (Statistics Canada, 2013c).

A cohort is a group of people who share a statistical or demographic trait. People belonging to the same age cohort were born in the same time frame. The population pyramids in Figure 13.3 show the different composition of age cohorts in the population, comparing the population in 2011 with figures projected for 2050. The bulge in the pyramid clearly becomes more rounded in the future, indicating that the proportion of senior cohorts will continue to increase with respect to the younger cohorts in the population. Understanding a population’s age composition can point to certain social and cultural factors and help governments and societies plan for future social and economic challenges. This is key to planning for everything from the funding of pension plans and health care systems to calculating the number of immigrants needed to replenish the workforce.

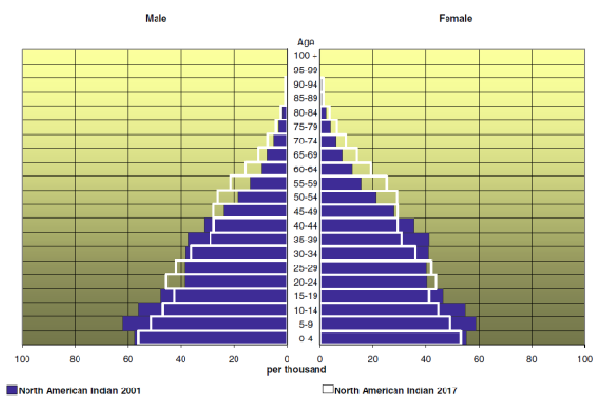

The population pyramid in Figure 13.4 compares the age distribution of the aboriginal population of Canada in 2001 to projected figures for 2017. It is much more pyramidal in form than the graphs for the Canadian population as a whole (see Figure 13.3) reflecting both the higher birth rate of the aboriginal population and the lower life expectancy of aboriginal people. The aboriginal population is much younger than the Canadian population as a whole, with a median age of 24.7 years in 2001 (projected to increase to 27.8 in 2017). Sociological studies on aging might help explain the difference between Native American age cohorts and the general population. While Native American societies have a strong tradition of revering their elders, they also have a lower life expectancy because of lack of access to quality health care.

Phases of Aging: The Young-Old, Middle-Old, and Old-Old

In Canada, all people over age 18 are considered adults, but there is a large difference between a person aged 21 and a person who is 45. More specific breakdowns, such as “young adult” and “middle-aged adult,” are helpful. In the same way, groupings are helpful in understanding the elderly. The elderly are often lumped together, grouping everyone over the age of 65. But a 65-year-old’s experience of life is much different than a 90-year-old’s.

The older adult population can be divided into three life-stage subgroups: the young-old (approximately 65–74), the middle-old (ages 75–84), and the old-old (over age 85). Today’s young-old age group is generally happier, healthier, and financially better off than the young-old of previous generations. In North America, people are better able to prepare for aging because resources are more widely available.

Also, many people are making proactive quality-of-life decisions about their old age while they are still young. In the past, family members made care decisions when an elderly person reached a health crisis, often leaving the elderly person with little choice about what would happen. The elderly are now able to choose housing, for example, that allows them some independence while still providing care when it is needed. Living wills, retirement planning, and medical powers of attorney are other concerns that are increasingly handled in advance.

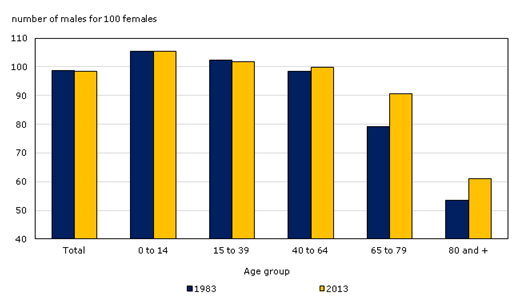

However, the gender imbalance in the sex ratio of men to women is increasingly skewed toward women as people age. In 2013, 67% of Canadians over the age of 85 were women (Statistics Canada, 2013b). This imbalance in life expectancy has larger implications because of the economic inequality between men and women. The population of old-old women are the cohort with the greatest needs for care, but because many women did not work outside the household during their working years and those who did earned less on average than men, they receive the least retirement benefits.

The Greying of Canada

What does it mean to be elderly? Some define it as an issue of physical health, while others simply define it by chronological age. The Canadian government, for example, typically classifies people aged 65 years old as elderly, at which point citizens are eligible for federal benefits such as Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security payments. The World Health Organization has no standard, other than noting that 65 years old is the commonly accepted definition in most core nations, but it suggests a cut-off somewhere between 50 and 55 years old for semi-peripheral nations, such as those in Africa (World Health Organization, 2012). CARP (formerly the Canadian Association of Retired Persons, now just known as CARP) no longer has an eligible age of membership because they suggest that people of all ages can begin to plan for their retirement. It is interesting to note CARP’s name change; by taking the word “retired”out of its name, the organization can broaden its base to any older Canadians, not just retirees. This is especially important now that many people are working to age 70 and beyond.

There is an element of social construction, both local and global, in the way individuals and nations define who is elderly; that is, the shared meaning of the concept of elderly is created through interactions among people in society. This is exemplified by the truism that you are only as old as you feel.

Demographically, the Canadian population over age 65 increased from 5% in 1901 (Novak, 1997) to 14.4% in 2011. Statistics Canada estimates that by 2051 the percentage will increase to 25.5% (Statistics Canada, 2010). This increase has been called “the greying of Canada,” a term that describes the phenomenon of a larger and larger proportion of the population getting older and older.

There are several reasons why Canada is greying so rapidly. One of these is life expectancy: the average number of years a person born today may expect to live. When reviewing Statistics Canada figures that group the elderly by age, it is clear that in Canada, at least, we are living longer. Between 1983 and 2013, the number of elderly citizens over 85 increased by more than 100%. In 2013 the number of centenarians (those 100 years or older) in Canada was 6,900, almost 20 centenarians per 100,000 persons, compared to 11 centenarians per 100,000 persons in 2001 (Statistics Canada, 2013b).

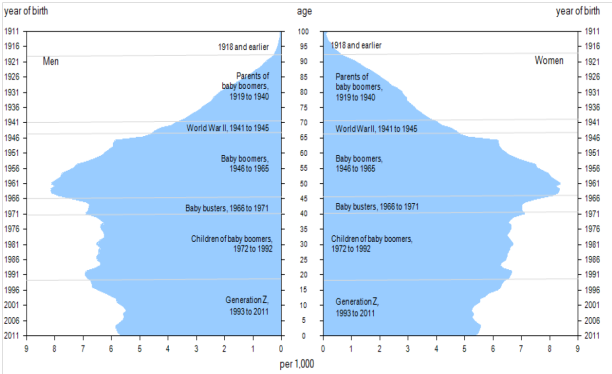

Another reason for the greying of Canada can be attributed to the aging of the baby boomers. Nearly a third of the Canadian population was born in the generation following World War II (between 1946 and 1964) when Canadian families averaged 3.7 children per family (compared to 1.7 today) (Statistics Canada, 2012a). Baby boomers began to reach the age of 65 in 2011. Finally, the proportion of old to young can be expected to continue to increase because of the below-replacement fertility rate (i.e., the average number of children per woman). A low birth rate contributes to the higher percentage of older people in the population.

As we noted above, not all Canadians age equally. Most glaring is the difference between men and women; as Figure 13.6 shows, women have longer life expectancies than men. In 2013, there were ninety 65-to-79-year-old men per one hundred 65-to-79-year-old women. However, there were only sixty 80+ year-old men per one hundred 80+ year-old women. Nevertheless, as the graph shows, the sex ratio actually increased over time, indicating that men are closing the gap between their life spans and those of women (Statistics Canada, 2013c).

Baby Boomers

Of particular interest to gerontologists right now are the consequences of the aging population of baby boomers, the cohort born between 1946 and 1964 and just now reaching age 65. Coming of age in the 1960s and early 1970s, the baby boom generation was the first group of children and teenagers with their own spending power and therefore their own marketing power (Macunovich, 2000). The youth market for commodities such as music, fashion, movies, and automobiles, was a major factor in creating a youth-oriented culture. As this group has aged, it has redefined what it means to be young, middle-aged, and, now, old. People in the boomer generation do not want to grow old the way their grandparents did; the result is a wide range of products designed to ward off the effects—or the signs—of aging. Previous generations of people over 65 were “old.” Baby boomers are in “later life” or “the third age” (Gilleard and Higgs, 2007).

The baby boom generation is the cohort driving much of the dramatic increase in the over-65 population. As we can see in Figure 13.7, the biggest bulge in the population pyramid for 2011 (representing the largest population group) is in the age 45 to 55 cohort. As time progresses, the population bulge moves up in age. In 2011 the oldest baby boomers were just reaching the age at which Statistics Canada considers them elderly. In 2020, we can predict, the baby boom bulge will continue to rise up the pyramid, making the largest Canadian population group between 65 and 85 years old.

This aging of the baby boom cohort has serious implications for society. Health care is one of the areas most impacted by this trend. For years, hand-wringing has abounded about the additional burden the boomer cohort will place on the publicly funded health care system. The report by the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada noted in 2001 that the combined public and private expenditure per person each year for medical care was approximately three times as much for persons over 65 than for the average person ($10,834 per person versus $3,174). As health care costs increase with age, the reasoning is that more people entering the 65 and older age group will increase the cost of medical care dramatically. In fact, the cost to the health care system specifically due to aging is projected to be no more than 1% per year (Romanow, 2002). The main sources of cost increase to the health care system come from inflation, rising overall population, and advances in medical technologies (new pharmaceutical drugs, surgical techniques, diagnostic and imaging techniques, and end-of-life care). With respect to end-of-life care, the average Canadian now receives approximately one and a half times more health care services than the average Canadian did in 1975 (Lee, 2007). Even with modest economic growth, existing levels of health care service can be maintained without difficulty if the total increase in costs of health care from all sources, including aging, result in an annual increase in health care budget expenditures of 4.4% over the medium term as expected (Lee, 2007).

Other studies indicate that aging boomers will bring economic growth to the health care industries, particularly in areas like pharmaceutical manufacturing and home health care services (Bierman, 2011). Further, some argue that many of our medical advances of the past few decades are a result of boomers’ health requirements. Unlike the elderly of previous generations, boomers do not expect that turning 65 means their active lives are over. They are not willing to abandon work or leisure activities, but they may need more medical support to keep living vigorous lives. This desire of a large group of over-65-year-olds wanting to continue with a high activity level is driving innovation in the medical industry (Shaw, 2012). It is not until the final year of life that health care expenditures undergo a dramatic increase. Approximately one-third to one-half of a typical person’s total health care expenditures occur in the final year of life (Lee, 2007). The implication is that with people living increasingly longer and healthier lives, the issue of the cost of health care and aging needs to be refocused on end-of-life care options.

The economic impact of aging boomers is also an area of concern for many observers. Although the baby boom generation earned more than previous generations and enjoyed a higher standard of living, they also spent their money lavishly and did not adequately prepare for retirement. According to a 2013 report from the Bank of Montreal, the average baby boomer falls about $400,000 short of adequate savings to maintain their lifestyles in retirement. The average senior couple spends approximately $54,000 a year, requiring accumulated savings of $1,352,000 to sustain themselves (not taking into account Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Pension payments). Canadian boomers anticipated they needed savings of $658,000 to feel financially secure in retirement but had only saved an average of $228,000. 71% of boomers said they plan to work part time in retirement (BMO Financial Group, 2013). This will have a ripple effect on the economy as boomers work and spend less.

Just as some observers are concerned about the possibility of the health care system being overburdened, the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans are also considered to be at risk given the longer life spans of seniors and low interest rates, according to the Auditor General’s 2014 report (CBC News, 2014). The Canada and Quebec Pension Plans are government-run retirement programs funded primarily through payroll taxes. In addition, seniors receive support from the Old Age Security (OAS) program and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (for those with low incomes). Together the pension plans, OAS, and Guaranteed Income Supplements are credited with successfully reducing old age poverty. Poverty rates for elderly couples were reduced from 17.7% to 2.4% between 1976 and 2011, for single men over 65 from 55.9% to 12.2%, and for single women over 65, from 68.1% to 16.1% (MacKenzie, 2014). Observers acknowledge that the systems are run very well, but their payments do not cover cost-of-living expenses, and in the absence of adequate retirement savings, the economic situation of retirees is threatened. With the aging boomer cohort starting to receive pension benefits, and with fewer workers paying into the pension trust fund, it is estimated that by 2021 the fund will have to start drawing on its investment income in order to make payments (Davidson, 2013). As a result, the government has raised the retirement age (the age at which people could start receiving retirement benefits) from 65 to 67, and many are arguing that CPP payments should be increased to ensure the system’s sustainability.

Aging around the World

From 1950 to approximately 2010, the global population of individuals age 65 and older increased by a range of 5 to 7% (Lee, 2009). This percentage is expected to increase and will have a huge impact on the dependency ratio: the number of productive working citizens to non-productive (young, disabled, elderly) (Bartram and Roe, 2005). One country that will soon face a serious aging crisis is China, which is on the cusp of an “aging boom”: a period when its elderly population will dramatically increase. The number of people above age 60 in China today is about 178 million, which amounts to 13.3% of its total population (Xuequan, 2011). By 2050, nearly a third of the Chinese population will be age 60 or older, putting a significant burden on the labour force and impacting China’s economic growth (Bannister, Bloom, and Rosenberg, 2010).

As health care improves and life expectancy increases across the world, elder care will be an emerging issue. Wienclaw (2009) suggests that with fewer working-age citizens available to provide home care and long-term assisted care to the elderly, the costs of elder care will increase.

Worldwide, the expectation governing the amount and type of elder care varies from culture to culture. For example, in Asia the responsibility for elder care lies firmly on the family (Yap, Thang, and Traphagan, 2005). This is different from the approach in most Western countries, where the elderly are considered independent and are expected to tend to their own care. It is not uncommon for family members to intervene only if the elderly relative requires assistance, often due to poor health. Even then, caring for the elderly is considered voluntary. In North America, decisions to care for an elderly relative are often conditionally based on the promise of future returns, such as inheritance or, in some cases, the amount of support the elderly provided to the caregiver in the past (Hashimoto, 1996).

These differences are based on cultural attitudes toward aging. In China, several studies have noted the attitude of filial piety (deference and respect to one’s parents and ancestors in all things) as defining all other virtues (Hamilton, 1990; Hsu, 1971). Cultural attitudes in Japan prior to approximately 1986 supported the idea that the elderly deserve assistance (Ogawa and Retherford, 1993). However, seismic shifts in major social institutions (like family and economy) have created an increased demand for community and government care. For example, the increase in women working outside the home has made it more difficult to provide in-home care to aging parents, leading to an increase in the need for government-supported institutions (Raikhola and Kuroki, 2009).

In North America, by contrast, many people view caring for the elderly as a burden. Even when there is a family member able and willing to provide for an elderly family member, 60% of family caregivers are employed outside the home and are unable to provide the needed support. At the same time, however, many middle-class families are unable to bear the financial burden of “outsourcing” professional health care, resulting in gaps in care (Bookman and Kimbrel, 2011). Chinese Canadians, for example, are thought to have a higher sense of filial responsibility and to perceive providing family assistance for the elderly as a more normal aspect of life than Caucasian Canadians (Funk, Chappell, and Liu, 2013). It is important to note that even within a country, not all demographic groups treat aging the same way. While most Americans are reluctant to place their elderly members into out-of-home assisted care, demographically speaking, the groups least likely to do so are Latinos, African Americans, and Asians (Bookman and Kimbrel, 2011).

Globally, Canada and other wealthy nations are fairly well equipped to handle the demands of an exponentially increasing elderly population. However, peripheral and semi-peripheral nations face similar increases without comparable resources. Poverty among elders is a concern, especially among elderly women. The feminization of the aging poor, evident in peripheral nations, is directly due to the number of elderly women in those countries who are single, illiterate, and not a part of the labour force (Mujahid, 2006).

In 2002, the Second World Assembly on Aging was held in Madrid, Spain, resulting in the Madrid Plan, an internationally coordinated effort to create comprehensive social policies to address the needs of the worldwide aging population. The plan identifies three themes to guide international policy on aging: 1) publicly acknowledging the global challenges caused by, and the global opportunities created by, a rising global population; 2) empowering the elderly; and 3) linking international policies on aging to international policies on development (Zelenev, 2008).

The Madrid Plan has not yet been successful in achieving all its aims. However, it has increased awareness of the various issues associated with a global aging population, as well as raising the international consciousness to the way that the factors influencing the vulnerability of the elderly (social exclusion, prejudice and discrimination, and a lack of socio-legal protection) overlap with other developmental issues (basic human rights, empowerment, and participation), leading to an increase in legal protections (Zelenev, 2008).

13.2. The Process of Aging

As human beings grow older, they go through different phases or stages of life. It is helpful to understand aging in the context of these phases as aging is not simply a physiological process. A life course is the period from birth to death, including a sequence of predictable life events such as physical maturation and the succession of age-related roles: child, adolescent, adult, parent, senior, etc. At each point in life, as an individual sheds previous roles and assumes new ones, new institutions or situations are involved, which require both learning and a revised self-definition. You are no longer a toddler, you are in kindergarten now! You are no longer a child, you are in high school now! You are no longer a student, you have a job now! You are no longer single, you are going to have a child now! You are no longer in mid-life, it is time to retire now! Each phase comes with different responsibilities and expectations, which of course vary by individual and culture. The fact that age-related roles and identities vary according to social determinations mean that the process of aging is much more significantly a social phenomenon than a biological phenomenon.

Children love to play and learn, looking forward to becoming preteens. As preteens begin to test their independence, they are eager to become teenagers. Teenagers anticipate the promises and challenges of adulthood. Adults become focused on creating families, building careers, and experiencing the world as an independent person. Finally, many adults look forward to old age as a wonderful time to enjoy life without as much pressure from work and family life. In old age, grandparenthood can provide many of the joys of parenthood without all the hard work that parenthood entails. As work responsibilities abate, old age may be a time to explore hobbies and activities that there was no time for earlier in life. But for other people, old age is not a phase looked forward to. Some people fear old age and do anything to “avoid” it, seeking medical and cosmetic fixes for the natural effects of age. These differing views on the life course are the result of the cultural values and norms into which people are socialized.

Through the phases of the life course, dependence and independence levels change. At birth, newborns are dependent on caregivers for everything. As babies become toddlers and toddlers become adolescents and then teenagers, they assert their independence more and more. Gradually, children are considered adults, responsible for their own lives, although the point at which this occurs is widely variable among individuals, families, and cultures.

As Riley (1978) notes, the process of aging is a lifelong process and entails maturation and change on physical, psychological, and social levels. Age, much like race, class, and gender, is a hierarchy in which some categories are more highly valued than others. For example, while many children look forward to gaining independence, Packer and Chasteen (2006) suggest that even in children, age prejudice leads both society and the young to view aging in a negative light. This, in turn, can lead to a widespread segregation between the old and the young at the institutional, societal, and cultural levels (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, 2006).

Dr. Ignatz Nascher and the Birth of Geriatrics

In the early 1900s, a New York physician named Dr. Ignatz Nascher coined the term geriatrics, a medical specialty focusing on the elderly. He created the word by combining two Greek words: geron (old man) and iatrikos (medical treatment). Nascher based his work on what he observed as a young medical student, when he saw many acutely ill elderly people who were diagnosed simply as “being old.” There was nothing medicine could do, his professors declared, about the syndrome of “old age.”

Nascher refused to accept this dismissive view, seeing it as medical neglect. He believed it was a doctor’s duty to prolong life and relieve suffering whenever possible. In 1914, he published his views in his book Geriatrics: The Diseases of Old Age and Their Treatment (Clarfield, 1990). Nascher saw the practice of caring for the elderly as separate from the practice of caring for the young, just as pediatrics (caring for children) is different from caring for grown adults (Clarfield, 1990)

Nascher had high hopes for his pioneering work. He wanted to treat the aging, especially those who were poor and had no one to care for them. Many of the elderly poor were sent to live in “almshouses,” or public old-age homes (Cole, 1993). Conditions were often terrible in these almshouses, where the aging were often sent and just forgotten.

As hard as it might be to believe today, Nascher’s approach was considered unique. At the time of Nascher’s death, in 1944, he was disappointed that the field of geriatrics had not made greater strides. In what ways are the elderly better off today than they were before Nascher’s ideas?

Biological Changes

Each person experiences age-related changes based on many factors. Biological factors such as molecular and cellular changes are called primary aging, while aging that occurs due to controllable factors such as lack of physical exercise and poor diet is called secondary aging (Whitbourne and Whitbourne, 2010).

Most people begin to see signs of aging after age 50 when they notice the physical markers of age. Skin becomes thinner, drier, and less elastic. Wrinkles form. Hair begins to thin and grey. Men prone to balding start losing hair. The difficulty or relative ease with which people adapt to these changes is dependent in part on the meaning given to aging by their particular culture. A culture that values youthfulness and beauty above all else leads to a negative perception of growing old. Conversely, a culture that reveres the elderly for their life experience and wisdom contributes to a more positive perception of what it means to grow old.

The effects of aging can feel daunting, and sometimes the fear of physical changes (like declining energy, food sensitivity, and loss of hearing and vision) is more challenging to deal with than the changes themselves. The way people perceive physical aging is largely dependent on how they were socialized. If people can accept the changes in their bodies as a natural process of aging, the changes will not seem as frightening.

According to the 2011 Canadian Community Health Survey, fewer people over 65 assessed their health as “excellent” or “very good” (46%) compared to the average of all Canadians aged 12 and older (60%) (Statistics Canada, 2013). The most frequently reported health issues for those over 65 included arthritis or rheumatism (44% of 65- to 74-year olds and 51% of 75+ year-olds), hypertension (40% of all seniors), cataracts (28% of 75+ year olds), back pain, and heart disease. Additionally, 480,600 people, or 1.5% of Canada’s population, suffered from some form of dementia such as Alzheimer’s, a figure predicted to rise to 1.13 million (or 2.8% of the Canadian population) by 2038 (Kembhavi, 2012). Parker and Thorslund (2006) found that while the trend is toward steady improvement in most disability measures, there is a concomitant increase in functional impairments (disability) and chronic diseases. At the same time, medical advances have reduced some of the disabling effects of those diseases (Crimmins, 2004).

Some impacts of aging are gender specific. Some of the disadvantages that aging women face rise from long-standing social gender roles. For example, the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) favours men over women, inasmuch as women do not earn CPP benefits for the unpaid labour they perform as an extension of their gender roles. In the health care field, elderly female patients are more likely than elderly men to see their health care concerns trivialized (Sharp, 1995) and are more like to have the health issues labelled psychosomatic (Munch, 2004). Another female-specific aspect of aging is that mass-media outlets often depict elderly females in terms of negative stereotypes and as less successful than older men (Bazzini and Mclntosh, 1997).

For men, the process of aging—and society’s response to and support of the experience—may be quite different. The gradual decrease in male sexual performance that occurs as a result of primary aging is medicalized and constructed as needing treatment (Marshall and Katz, 2002) so that a man may maintain a sense of youthful masculinity. On the other hand, aging men have fewer opportunities to assert the masculine identities in the company of other men (e.g., sports participation) (Drummond, 1998). Some social scientists have observed that the aging male body is depicted in the Western world as genderless (Spector-Mersel, 2006).

Social and Psychological Changes

Male or female, growing older means confronting the psychological issues that come with entering the last phase of life. Young people moving into adulthood take on new roles and responsibilities as their lives expand, but an opposite arc can be observed in old age. What are the hallmarks of social and psychological change?

Retirement — the idea that one may stop working at a certain age — is a relatively recent idea. Up until the late 19th century, people worked about 60 hours a week and did so until they were physically incapable of continuing. In 1889, Germany was the first country to introduce a social insurance program that provided relief from poverty for seniors. At the request of the German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, the German emperor wrote to the German parliament: “those who are disabled from work by age and invalidity have a well-grounded claim to care from the state” (U.S. Social Security Administration, N.d.). The retirement age was initially set at age 70. In Canada, early Labour MPs (a precursor to the CCF and then the NDP) agreed to support the minority Liberal government, elected in 1925, in exchange for the introduction of the first Old Age Pensions Act (1927). In 1951 the Old Age Security Act was passed, creating the contemporary Old Age Security system, and in 1966 the Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan were introduced. These plans continued to provide benefits to seniors at age 70, but by 1971 age 65 had been gradually phased in (Canadian Museum of History, N.d.).

In the 21st century, most people hope that at some point they will be able to stop working and enjoy the fruits of their labour. But do people look forward to this time or do they fear it? When people retire from familiar work routines, some easily seek new hobbies, interests, and forms of recreation. Many find new groups and explore new activities, but others may find it more difficult to adapt to new routines and loss of social roles, losing their sense of self-worth in the process.

Each phase of life has challenges that come with the potential for fear. Erik H. Erikson (1902–1994), in his view of socialization, broke the typical life span into eight phases. Each phase presents a particular challenge that must be overcome. In the final stage, old age, the challenge is to embrace integrity over despair. Some people are unable to successfully overcome the challenge. They may have to confront regrets, such as being disappointed in their children’s lives or perhaps their own. They may have to accept that they will never reach certain career goals. Or they must come to terms with what their career success has cost them, such as time with their family or declining personal health. Others, however, are able to achieve a strong sense of integrity, embracing the new phase in life. When that happens, there is tremendous potential for creativity. They can learn new skills, practise new activities, and peacefully prepare for the end of life.

For some, overcoming despair might entail remarriage after the death of a spouse. A study conducted by Kate Davidson (2002) reviewed demographic data that asserted men were more likely to remarry after the death of a spouse, and suggested that widows (the surviving female spouse of a deceased male partner) and widowers (the surviving male spouse of a deceased female partner) experience their postmarital lives differently. Many surviving women enjoyed a new sense of freedom, as many were living alone for the first time. On the other hand, for surviving men, there was a greater sense of having lost something, as they were now deprived of a constant source of care as well as the focus on their emotional life.

Aging and Sexuality

It is no secret that Canadians are squeamish about the subject of sex. When the subject is the sexuality of elderly people no one wants to think about it or even talk about it. That fact is part of what makes the 1971 cult classic movie, Harold and Maude, so provocative. In this cult favourite film, Harold, an alienated, young man, meets and falls in love with Maude, a 79-year-old woman. What is so telling about the film is the reaction of his family, priest, and psychologist, who exhibit disgust and horror at such a match.

Although it is difficult to have an open, public national dialogue about aging and sexuality, the reality is that our sexual selves do not disappear after age 65. People continue to enjoy sex — and not always safe sex — well into their later years. In fact, some research suggests that as many as one in five new cases of AIDS occur in adults over 65 (Hillman, 2011).

In some ways, old age may be a time to enjoy sex more, not less. For women, the elder years can bring a sense of relief as the fear of an unwanted pregnancy is removed and the children are grown and taking care of themselves. However, while we have expanded the number of psycho-pharmaceuticals to address sexual dysfunction in men, it was not until very recently that the medical field acknowledged the existence of female sexual dysfunctions (Bryant, 2004).

Aging “Out:” LGBT Seniors

How do different groups in our society experience the aging process? Are there any experiences that are universal, or do different populations have different experiences? An emerging field of study looks at how lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people experience the aging process and how their experience differs from that of other groups or the dominant group. This issue is expanding with the aging of the baby boom generation; not only will aging boomers represent a huge bump in the general elderly population, but the number of LGBT seniors is expected to double by 2030 (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011).

A recent study titled The Aging and Health Report: Disparities and Resilience among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults finds that LGBT older adults have higher rates of disability and depression than their heterosexual peers. They are also less likely to have a support system that might provide elder care: a partner and supportive children (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Even for those LGBT seniors who are partnered, in the United States some states do not recognize a legal relationship between two people of the same sex, reducing their legal protection and financial options. In Canada, Supreme Court decisions in 2003 and the Civil Marriage Act in 2005 legalized same sex marriage.

As they transition to assisted-living facilities, LGBT people have the added burden of “disclosure management:” the way they share their sexual and relationship identity. In one case study, a 78-year-old lesbian lived alone in a long-term care facility. She had been in a long-term relationship of 32 years and had been visibly active in the gay community earlier in her life. However, in the long-term care setting, she was much quieter about her sexual orientation. She “selectively disclosed” her sexual identity, feeling safer with anonymity and silence (Jenkins et al., 2010). A study from the National Senior Citizens Law Center reports that only 22% of LGBT older adults expect they could be open about their sexual orientation or gender identity in a long-term care facility. Even more telling is the finding that only 16% of non-LGBT older adults expected that LGBT people could be open with facility staff (National Senior Citizens Law Center, 2011).

Same-sex marriage can have major implications for the way the LGBT community ages. With marriage comes the legal and financial protection afforded to opposite-sex couples, as well as less fear of exposure and a reduction in the need to “retreat to the closet” (Jenkins et al., 2010).

Death and Dying

For most of human history, the standard of living was significantly lower than it is now. Humans struggled to survive with few amenities and very limited medical technology. The risk of death due to disease or accident was high in any life stage, and life expectancy was low. As people began to live longer, death became associated with old age.

For many teenagers and young adults, losing a grandparent or another older relative can be the first loss of a loved one they experience. It may be their first encounter with grief, a psychological, emotional, and social response to the feelings of loss that accompanies death or a similar event.

People tend to perceive death, their own and that of others, based on the values of their culture. While some may look upon death as the natural conclusion to a long, fruitful life, others may find the prospect of dying frightening to contemplate. People tend to have strong resistance to the idea of their own death, and strong emotional reactions of loss to the death of loved ones. Viewing death as a loss, as opposed to a natural or tranquil transition, is often considered normal in North America.

What may be surprising is how few studies were conducted on death and dying prior to the 1960s. Death and dying were fields that had received little attention until psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began observing people who were in the process of dying. As Kübler-Ross witnessed people’s transition toward death, she found some common threads in their experiences. She observed that the process had five distinct stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. She published her findings in a 1969 book called On Death and Dying. The book remains a classic on the topic today.

Kübler-Ross found that a person’s first reaction to the prospect of dying is denial, characterized by not wanting to believe that they are dying, with common thoughts such as “I feel fine” or “This is not really happening to me.” The second stage is anger, when loss of life is seen as unfair and unjust. A person then resorts to the third stage, bargaining: trying to negotiate with a higher power to postpone the inevitable by reforming or changing the way they live. The fourth stage, psychological depression, allows for resignation as the situation begins to seem hopeless. In the final stage, a person adjusts to the idea of death and reaches acceptance. At this point, the person can face death honestly, regarding it as a natural and inevitable part of life, and can make the most of their remaining time.

The work of Kübler-Ross was eye-opening when it was introduced. It broke new ground and opened the doors for sociologists, social workers, health practitioners, and therapists to study death and help those who were facing death. Kübler-Ross’s work is generally considered a major contribution to thanatology: the systematic study of death and dying.

Of special interests to thanatologists is the concept of “dying with dignity.” Modern medicine includes advanced medical technology that may prolong life without a parallel improvement to the quality of life one may have. In some cases, people may not want to continue living when they are in constant pain and no longer enjoying life. Should patients have the right to choose to die with dignity? Dr. Jack Kevorkian was a staunch advocate for physician-assisted suicide: the voluntary or physician-assisted use of lethal medication provided by a medical doctor to end one’s life. Physician-assisted suicide is slightly different from euthanasia, which refers to the act of taking someone’s life to alleviate that person’s suffering, but that does not necessarily reflect the person’s expressed desire to commit suicide.

This right to have a doctor help a patient die with dignity is controversial. In the United States, Oregon was the first state to pass a law allowing physician-assisted suicides. In 1997, Oregon instituted the Death with Dignity Act, which required the presence of two physicians for a legal assisted suicide. This law was successfully challenged by U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft in 2001, but the appeals process ultimately upheld the Oregon law. Subsequently, both Montana and Washington have passed similar laws.

In Canada, physician-assisted suicide is illegal, although suicide itself has not been illegal since 1972. On moral and legal grounds, advocates of physician-assisted suicide argue that the law unduly deprives individuals of their autonomy and right to freely choose to end their own life with assistance; that existing palliative care can be inadequate to alleviate pain and suffering; that the law discriminates against disabled people who are unable, unlike able-bodied people, to commit suicide by themselves; and that assisted suicide is taking place already in an informal way, but without proper regulations. Those opposed argue that life is a fundamental value and killing is intrinsically wrong, that legal physician-assisted suicide could result in abuses with respect to the most vulnerable members of society, that individuals might seek assisted suicide for financial reasons or because services are inadequate, and that it might reduce the urgency to find means of improving the care of people who are dying (Butler, Tiedemann, Nicol, and Valiquet, 2013).

There are two main legal reference points for the issue in Canada. One is the case of Robert Latimer, the Saskatchewan farmer convicted in 1997 for the mercy killing (or euthanasia) of his 12-year-old daughter, Tracey Latimer, who had a severe form of cerebral palsy, and was unable walk, talk, or feed herself. The second case is that of Sue Rodriguez who sought the legal right to have a physician-assisted suicide because she suffered from ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). She argued in the Supreme Court that the law against physician-assisted suicide violated her right to “life, liberty, and security of the person” but lost her case in a five-to-four decision in 1992. She did choose physician-assisted suicide two years later from an anonymous physician. In 2012, however, a B.C. court found that the law did discriminate against those who are “grievously and irremediably ill” in the case of Gloria Taylor, another woman with ALS. The court granted a constitutional exemption to permit her to seek physician-assisted suicide while the constitutional challenge to the law is clarified. However, Taylor died from an infection in 2012. The constitutional challenge to the law remains unresolved. In Quebec, the Select Committee on Dying with Dignity tabled a report in 2012 that supported assisted suicide. In 2013 a panel of experts appointed by the Quebec government agreed that in certain circumstances assisted suicide should be understood as part of the continuum of care (Butler et al., 2013). In 2014, Quebec became the first province in Canada to pass right-to-die legislation. Terminally ill adults of sound mind may request continuous palliative sedation that will lead to death (Seguin, 2014).

The controversy surrounding death with dignity laws is emblematic of the way our society tries to separate itself from death. Health institutions have built facilities to comfortably house those who are terminally ill. This is seen as a compassionate act, helping relieve the surviving family members of the burden of caring for the dying relative. But studies almost universally show that people prefer to die in their own homes (Lloyd, White, and Sutton, 2011). Is it our social responsibility to care for elderly relatives up until their death? How do we balance the responsibility for caring for an elderly relative with our other responsibilities and obligations? As our society grows older, and as new medical technology can prolong life even further, the answers to these questions will develop and change.

The changing concept of hospice is an indicator of our society’s changing view of death. Hospice is a type of health care that treats terminally ill people when cure-oriented treatments are no longer an option (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, N.d.). Hospice doctors, nurses, and therapists receive special training in the care of the dying. The focus is not on getting better or curing the illness, but on passing out of this life in comfort and peace. Hospice centres exist as places where people can go to die in comfort, and increasingly, hospice services encourage at-home care so that someone has the comfort of dying in a familiar environment, surrounded by family (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, N.d.). While many of us would probably prefer to avoid thinking of the end of our lives, it may be possible to take comfort in the idea that when we do approach death in a hospice setting, it is in a familiar, relatively controlled place.

13.3. Challenges Facing the Elderly

Aging comes with many challenges. The loss of independence is one potential part of the process, as are diminished physical ability and age discrimination. The term senescence refers to the aging process, including biological, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual changes. This section discusses some of the challenges we encounter during this process.

As already observed, many older adults remain highly self-sufficient. Others require more care. Because the elderly typically no longer hold jobs, finances can be a challenge. Due to cultural misconceptions, older people can be targets of ridicule and stereotypes. The elderly face many challenges in later life, but they do not have to enter old age without dignity.

Ageism

Driving to the grocery store, Peter, 23, got stuck behind a car on a four-lane main artery through his city’s business district. The speed limit was 50 kilometres per hour, and while most drivers sped along at 60 to 70 kilometres per hour, the driver in front of him was going the speed limit. Peter tapped on his horn. He tailgated the driver. Finally, Peter had a chance to pass the car. He glanced over. Sure enough, Peter thought, a grey-haired old man guilty of “DWE,” driving while elderly.

At the grocery store, Peter waited in the checkout line behind an older woman. She paid for her groceries, lifted her bags of food into her cart, and toddled toward the exit. Peter, guessing her to be about 80, was reminded of his grandmother. He paid for his groceries and caught up with her.

“Can I help you with your cart?” he asked.

“No, thank you. I can get it myself,” she said and marched off toward her car.

Peter’s responses to both older people, the driver and the shopper, were prejudiced. In both cases, he made unfair assumptions. He assumed the driver drove cautiously simply because the man was a senior citizen, and he assumed the shopper needed help carrying her groceries just because she was an older woman.

Responses like Peter’s toward older people are fairly common. He didn’t intend to treat people differently based on personal or cultural biases, but he did. Ageism is discrimination (when someone acts on a prejudice) based on age. Dr. Robert Butler coined the term in 1968, noting that ageism exists in all cultures (Brownell, 2010). Ageist attitudes and biases based on stereotypes reduce elderly people to inferior or limited positions.

Ageism can vary in severity. Peter’s attitudes are probably seen as fairly mild, but relating to the elderly in ways that are patronizing can be offensive. When ageism is reflected in the workplace, in health care, and in assisted-living facilities, the effects of discrimination can be more severe. Ageism can make older people fear losing a job, feel dismissed by a doctor, or feel a lack of power and control in their daily living situations.

In early societies, the elderly were respected and revered. Many preindustrial societies observed gerontocracy, a type of social structure wherein the power is held by a society’s oldest members. In some countries today, the elderly still have influence and power and their vast knowledge is respected.

In many modern nations, however, industrialization contributed to the diminished social standing of the elderly. Today wealth, power, and prestige are also held by those in younger age brackets. The average age of corporate executives was 59 in 1980. In 2008, the average age had lowered to 54 (Stuart, 2008). Some older members of the workforce felt threatened by this trend and grew concerned that younger employees in higher-level positions would push them out of the job market. Rapid advancements in technology and media have required new skill sets that older members of the workforce are less likely to have.

Changes happened not only in the workplace but also at home. In agrarian societies, a married couple cared for their aging parents. The oldest members of the family contributed to the household by doing chores, cooking, and helping with child care. As economies shifted from agrarian to industrial, younger generations moved to cities to work in factories. The elderly began to be seen as an expensive burden. They did not have the strength and stamina to work outside the home. What began during industrialization, a trend toward older people living apart from their grown children, has become commonplace.

Mistreatment and Abuse

Mistreatment and abuse of the elderly is a major social problem. As expected, with the biology of aging, the elderly sometimes become physically frail. This frailty renders them dependent on others for care — sometimes for small needs like household tasks, and sometimes for assistance with basic functions like eating and toileting. Unlike a child, who also is dependent on another for care, an elder is an adult with a lifetime of experience, knowledge, and opinions — a more fully developed person. This makes the care providing situation more complex.

Elder abuse describes when a caretaker intentionally deprives an older person of care or harms the person in their charge. Caregivers may be family members, relatives, friends, health professionals, or employees of senior housing or nursing care. The elderly may be subject to many different types of abuse.

In a 2009 study on the topic led by Dr. Ron Acierno, the team of researchers identified five major categories of elder abuse: 1) physical abuse, such as hitting or shaking, 2) sexual abuse including rape and coerced nudity, 3) psychological or emotional abuse, such as verbal harassment or humiliation, 4) neglect or failure to provide adequate care, and 5) financial abuse or exploitation (Acierno, 2010).

The National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) in the United States also identifies abandonment and self-neglect as types of abuse. Table 13.1 (below) shows some of the signs and symptoms that the NCEA encourages people to notice.

| Type of Abuse | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Physical abuse | Bruises, untreated wounds, sprains, broken glasses, lab findings of medication overdose |

| Sexual abuse | Bruises around breasts or genitals, torn or bloody underclothing, unexplained venereal disease |

| Emotional/ psychological abuse | Being upset or withdrawn, unusual dementia-like behaviour (rocking, sucking) |

| Neglect | Poor hygiene, untreated bed sores, dehydration, soiled bedding |

| Financial | Sudden changes in banking practices, inclusion of additional names on bank cards, abrupt changes to will |

| Self-neglect | Untreated medical conditions, unclean living area, lack of medical items like dentures or glasses |

How prevalent is elder abuse? In 2009, Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey reported that 2% of men and 3% of women said that they had been emotionally or financially abused by a child, relative, friend, or caregiver in the five years preceding the survey. Incidents of both self-reported violence and police-reported violence against elders are much lower than for other age groups in the population (Brennan, 2012). Some social researchers believe elder abuse is underreported and that the number may be higher. The risk of abuse also increases in people with health issues such as dementia (Kohn and Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2011). Older women were found to be victims of verbal abuse more often than their male counterparts.

In Acierno’s study, which included a sample of 5,777 respondents age 60 and older, 5.2% of respondents reported financial abuse, 5.1% said they’d been neglected, and 4.6% endured emotional abuse (Acierno, 2010). The prevalence of physical and sexual abuse was lower at 1.6 and 0.6%, respectively (Acierno, 2010).

Other studies have focused on the caregivers to the elderly in an attempt to discover the causes of elder abuse. Researchers identified factors that increased the likelihood of caregivers perpetrating abuse against those in their care. Those factors include inexperience, having other demands such as jobs (for those who weren’t professionally employed as caregivers), caring for children, living full time with the dependent elder, and experiencing high stress, isolation, and lack of support (Kohn and Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2011).

A history of depression in the caregiver was also found to increase the likelihood of elder abuse. Neglect was more likely when care was provided by paid caregivers. Many of the caregivers who physically abused elders were themselves abused — in many cases, when they were children. Family members with some sort of dependency on the elder in their care were more likely to physically abuse that elder. For example, an adult child caring for an elderly parent while, at the same time, depending on some form of income from that parent, would be considered more likely to perpetrate physical abuse (Kohn and Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2011).

A survey found that 60.1% of caregivers reported verbal aggression as a style of conflict resolution. Paid caregivers in nursing homes were at a high risk of becoming abusive if they had low job satisfaction, treated the elderly like children, or felt burnt out (Kohn and Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2011). Caregivers who tended to be verbally abusive were found to have had less training, lower education, and higher likelihood of depression or other psychiatric disorders. Based on the results of these studies, many housing facilities for seniors have increased their screening procedures for caregiver applicants.

13.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Aging

What roles do individual senior citizens play in your life? How do you relate to and interact with older people? What role do they play in neighbourhoods and communities, in cities and in provinces? Sociologists are interested in exploring the answers to questions such as these through a variety of different perspectives including functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and critical sociology.

Functionalism

Functionalists analyze how the parts of society work together to create a state of equilibrium. They gauge how each part of society functions to keep society running smoothly. How does this perspective address aging? Structural functionalists argue that each age performs a specific function in society. Much of the focus in this approach is on how the elderly, as a group, cope with the functional transition of roles as they move into the senior stage of life. How do individuals adapt to the different roles, norms, and expectations of old age, and to their changing physical and mental capacities?

Functionalists find that people with better resources who stay active in other roles adjust better to old age (Crosnoe and Elder, 2002). Three social theories within the functional perspective were developed to explain how older people might deal with later-life experiences.

The earliest gerontological theory in the functionalist perspective is disengagement theory, which suggests that withdrawing from society and social relationships is a natural part of growing old. There are several main points to the theory. First, because everyone expects to die one day, and because we experience physical and mental decline as we approach death, it is natural to withdraw from individuals and society. Second, as the elderly withdraw, they receive less reinforcement to conform to social norms. Therefore, this withdrawal allows a greater freedom from the pressure to conform. Finally, social withdrawal is gendered, meaning it is experienced differently by men and women. Because men focus on work and women focus on marriage and family, when they withdraw they will be unhappy and directionless until they adopt a role to replace their accustomed role that is compatible with the disengaged state (Cumming and Henry, 1961).

The suggestion that old age was a distinct state in the life course, characterized by a distinct change in roles and activities, was groundbreaking when it was first introduced. However, the theory is no longer accepted in its classic form. Criticisms typically focus on the application of the idea that seniors universally naturally withdraw from society as they age, and that it does not allow for a wide variation in the way people experience aging (Hothschild, 1975).

The social withdrawal that Cumming and Henry recognized (1961), and its notion that elderly people need to find replacement roles for those they have lost, is addressed anew in activity theory. According to this theory, activity levels and social involvement are key to this process, and key to happiness (Havinghurst, 1961; Havinghurst, Neugarten, and Tobin, 1968; Neugarten, 1964). According to this theory, the more active and involved an elderly person is, the happier they will be. Critics of this theory point out that access to social opportunities and activity are not equally available to all. The theory proposes that activity is a solution to the well-being of seniors without being able to account for how the distribution of access to these social opportunities and activities reflects broader issues of power and inequality in society. Moreover, not everyone finds fulfillment in the presence of others or participation in activities. Reformulations of this theory suggest that participation in informal activities, such as hobbies, are what most effect later life satisfaction (Lemon, Bengtson, and Petersen, 1972).

According to continuity theory, the elderly do not drastically change their lifestyles, behaviours, or identities. They make specific choices to maintain consistency in internal personality structures and beliefs, and external structures (e.g., relationships), remaining active and involved throughout their elder years. The focus of this approach is to examine how the elderly attempt to maintain social equilibrium and stability by making future decisions on the basis of already developed social roles (Atchley, 1971; Atchley, 1989). One criticism of this theory is its emphasis on creating a model of “normal” aging, which is inadequate as a description of those with chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s, and tends to treat “non-normal” aging as pathological.

The Greying of North American Prisons

Earl Grimes is a 79-year-old inmate. He has undergone two cataract surgeries and takes about $1,000 a month worth of medication to manage a heart condition. He needs significant help moving around, which he obtains by bribing younger inmates. He is serving a life prison term for a murder he committed 38 years — half a lifetime — ago (Warren, 2002).

Grimes’ situation exemplifies the problems facing prisons today. According to the Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator in 2011, more than 20% of prisoners are age 50 or older in the Canadian prison population. Age 50 is used as a benchmark of the elderliness of offenders because it is generally recognized that the aging process is accelerated by ten years in prison due to the effects of incarceration. These numbers represent a 50% rise over the last decade (Sapers, 2011). The main factor influencing today’s aging prison population is the aging of the overall population. As discussed in the section on aging in Canada, the percentage of people over 65 is increasing each year due to rising life expectancies and the aging of the baby boom generation.

So why should it matter that the elderly prison population is growing so swiftly? As discussed in the section on the process of aging, growing older is accompanied by a host of physical problems, such as failing vision, mobility, and hearing. Chronic illnesses such as heart disease, arthritis, and diabetes also become increasingly common as people age, whether they are in prison or not. Unfortunately prisons were not designed with the elderly in mind and those with physical mobility and sight impairments are particularly affected. There is also a threat to their physical well-being from younger inmates as the elderly have little social status within the institution. Ex-inmate Walter Noonan (aged 55) notes that respect for the elderly in prison has declined drastically over the last 10 years. Older inmates are isolated and often afraid of younger inmates who increasingly have drug and psychiatric problems or have gang affiliations and seek to make a name for themselves using violence (Edwards, 2014).

In many cases, elderly prisoners are physically incapable of committing a violent — or possibly any — crime. Is it ethical to keep them locked up for the short remainder of their lives? There seem to be many reasons, both financial and ethical, to release some elderly prisoners to live the rest of their lives — and die — in freedom. However, few lawmakers are willing to appear soft on crime by releasing convicted felons from prison, especially if their sentence was “life without parole” (Warren, 2002).

Critical Sociology

Theorists working the critical perspective view society as inherently unstable, based on power relationships that privilege the powerful wealthy few while marginalizing everyone else. According to the guiding principle of critical sociology, the imbalance of power and access to resources between groups is an issue of social justice that needs to be addressed. Applied to society’s aging population, the principle means that the elderly struggle with other groups — for example, younger society members — to retain a certain share of resources. At some point, this competition may become conflict.

For example, some people complain that the elderly get more than their fair share of society’s resources. In hard economic times, there is great concern about the huge costs of social security and health care. They argue that the medical bills of the nation’s elderly population are rising dramatically, taking resources away from the needs of other segments of the population like education. For example, while funding for education is cut back, funding for medical research increases. However, while there is more care available to certain segments of the senior community, it must be noted that the financial resources available to the aging can vary tremendously by race, social class, and gender.

There are three classic theories of aging within the critical perspective. Modernization theory (Cowgill and Holmes, 1972) suggests that the primary cause of the elderly losing power and influence in society are the parallel forces of industrialization and modernization. As societies modernize, the status of elders decreases, and they are increasingly likely to experience social exclusion. Before industrialization, strong social norms bound the younger generation to care for the older. Now, as societies industrialize, the nuclear family replaces the extended family. With increasingly precarious employment, the struggle to earn a living means that people often have to move away from family to work and the work itself consumes increasing time and energy that might be spent looking after family members. Societies become increasingly individualistic, and norms regarding the care of older people change. In an individualistic industrial society, caring for an elderly relative is seen as a voluntary obligation that may be ignored without fear of social censure.

The central reasoning of modernization theory is that as long as the extended family is the standard family, as in preindustrial economies, elders will have a place in society and a clearly defined role. As societies modernize, the elderly, unable to work outside of the home, have less to offer economically and are seen as a burden. This model may be applied to both the developed and the developing world, and it suggests that as people age they will be abandoned and lose much of their familial support since they become a nonproductive economic burden.

Another theory in the critical perspective is age stratification theory (Riley, Johnson, and Foner, 1972). Though it may seem obvious now, with our awareness of ageism, age stratification theorists were the first to suggest that members of society might be stratified by age, just as they are stratified by race, class, and gender. The value of a person (i.e., their status or prestige in society) is determined by their age, an ascribed rather than an achieved characteristic. Because age serves as a basis of social control, different age groups have varying access to social resources such as political and economic power. In this model, the privileges, independence, and access to social resources of seniors decreases based simply on their position within an age-category hierarchy. The elderly experience an increased dependence as they age and must increasingly submit to the will of others because they have fewer ways of compelling others to submit to them. Moreover, within societies stratified by age, behavioural age norms, including norms about roles and appropriate behaviour, dictate what members of age cohorts may reasonably do. For example, it might be considered deviant for an elderly woman to wear a bikini because it violates norms denying the sexuality of older females. These norms are specific to each age strata, developing from culturally based ideas about how people should “act their age.”

Thanks to amendments to recent legislation in all provinces (except New Brunswick), Canadian workers no longer must retire upon reaching a specified age. Age is one of the prohibited grounds of discrimination in employment across Canada.

Age stratification theory has been criticized for its broadness and its inattention to other sources of stratification and how these might intersect with age. Feminist theory argues that an older white male occupies a more powerful role, and is far less limited in his choices, than an older white female based on his historical access to political and economic power. In other words, gender is a key variable needed to understand the issues of aging. Women’s status has traditionally depended much more on youth and physical attractiveness than men’s, so the devaluation associated with aging affects them much more powerfully.

In addition, women’s earnings do not increase at the same rate as men’s in the latter half of their careers so more women enter retirement age with considerably less financial resources than men (Garner, 1999). In 2007, the low-income rate for senior, single, unattached women was 14%. About 123,000 senior women living on their own lived in poverty compared to 44,000 men (Townsend, 2009).

Finally, many senior women today were socialized in their experience as daughters and wives to grant the decision-making power to men, especially in the area of financial decision making. When they outlive their spouses, they are often suddenly burdened with decisions and tasks with which they they have had no experience. This can be profoundly disempowering, particularly when adult children feel they need to step in and take over. As feminist critique is not simply about drawing attention to the injustice of women’s position in society, the question then becomes, how can senior women be empowered to develop new roles, recognize their strengths, and see themselves as valuable human beings (Garner, 1999)?

Symbolic Interactionism

Generally, theories within the symbolic interactionist perspective focus on how society is created through the day-to-day interaction of individuals, as well as the way people perceive themselves and others based on cultural symbols. This microanalytic perspective assumes that if people develop a sense of identity through their social interactions, their sense of self is dependent on those interactions. A woman whose main interactions with society make her feel old and unattractive may lose her sense of self. But a woman whose interactions make her feel valued and important will have a stronger sense of self and a happier life.