Main Body

Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Ron McGivern

Learning Objectives

- Define technology and describe its evolution.

- Understand technological inequality and issues related to unequal access to technology.

- Describe the role of planned obsolescence in technological development.

8.2. Media and Technology in Society

- Describe the evolution and current role of different media, like newspapers, television, and new media.

- Understand the function of product advertising in media.

- Demonstrate awareness of the social homogenization and social fragmentation that are occurring via modern society’s use of technology and media.

- Explain the advantages and concerns of media globalization.

- Understand the globalization of technology.

8.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

- Understand and discuss how media and technology are analyzed through various sociological perspectives.

Introduction to Media and Technology

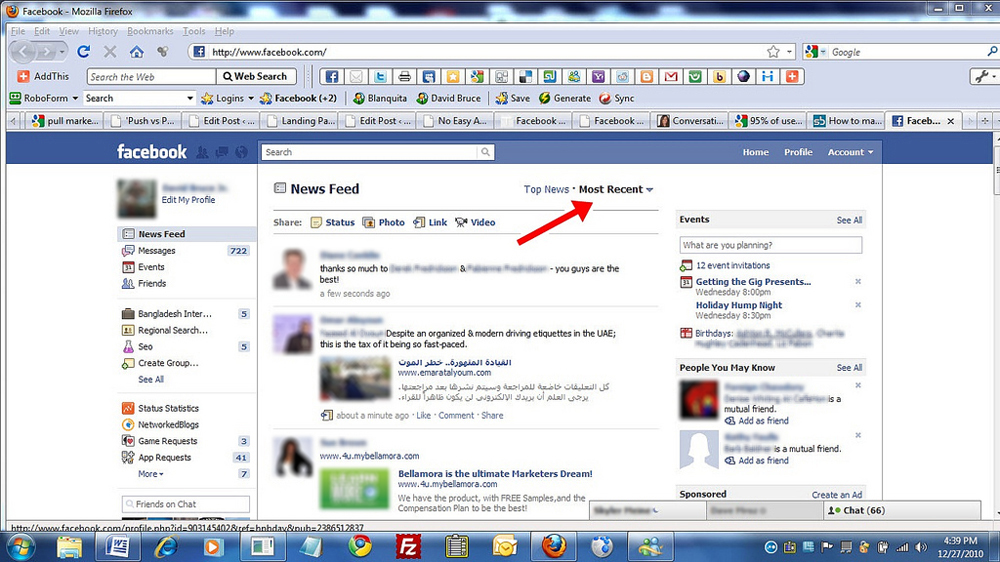

How many good friends do you have? How many people do you meet for coffee or a movie? How many would you call with news about an illness or invite to your wedding? Now, how many “friends” do you have on Facebook? Technology has changed how we interact with each other. It has turned “friend” into a verb and has made it possible to share mundane news (“My dog just threw up under the bed! Ugh!”) with hundreds or even thousands of people who might know you only slightly, if at all. Through the magic of Facebook, you might know about an old elementary school friend’s new job before her mother does. By thinking of everyone as fair game in networking for personal gain, we can now market ourselves professionally to the world with LinkedIn.

At the same time that technology is expanding the boundaries of our social circles, various media are also changing how we perceive and interact with each other. We do not only use Facebook to keep in touch with friends; we also use it to “like” certain TV shows, products, or celebrities. Even television is no longer a one-way medium but an interactive one. We are encouraged to tweet, text, or call in to vote for contestants in everything from singing competitions to matchmaking endeavours — bridging the gap between our entertainment and our own lives.

How does technology change our lives for the better? Or does it? When you tweet a social cause or cut and paste a status update about cancer awareness on Facebook, are you promoting social change? Does the immediate and constant flow of information mean we are more aware and engaged than any society before us? Or are TV reality shows and talent competitions today’s version of ancient Rome’s “bread and circuses” — distractions and entertainment to keep the lower classes indifferent to the inequities of our society? Do media and technology liberate us from gender stereotypes and provide us with a more cosmopolitan understanding of each other, or have they become another tool in promoting misogyny? Is ethnic and gay and lesbian intolerance being promoted through a ceaseless barrage of minority stereotyping in movies, video games, and websites?

These are some of the questions that interest sociologists. How might we examine these issues from a sociological perspective? A structural functionalist would probably focus on what social purposes technology and media serve. For example, the web is both a form of technology and a form of media, and it links individuals and nations in a communication network that facilitates both small family discussions and global trade networks. A functionalist would also be interested in the manifest functions of media and technology, as well as their role in social dysfunction. Someone applying the critical perspective would probably focus on the systematic inequality created by differential access to media and technology. For example, how can Canadians be sure the news they hear is an objective account of reality, unsullied by moneyed political interests? Someone applying the interactionist perspective to technology and the media might seek to understand the difference between the real lives we lead and the reality depicted on “reality” television shows, such as the U.S., based but Canadian MTV production Jersey Shore, with up to 800,000 Canadian viewers (Vlessing, 2011). Throughout this chapter, we will use our sociological imagination to explore how media and technology impact society.

8.1. Technology Today

It is easy to look at the latest sleek tiny Apple product and think that technology is only recently a part of our world. But from the steam engine to the most cutting-edge robotic surgery tools, technology describes the application of science to address the problems of daily life. We might look back at the enormous and clunky computers of the 1970s that had about as much storage as an iPod Shuffle and roll our eyes in disbelief. But chances are 30 years from now our skinny laptops and MP3 players will look just as archaic.

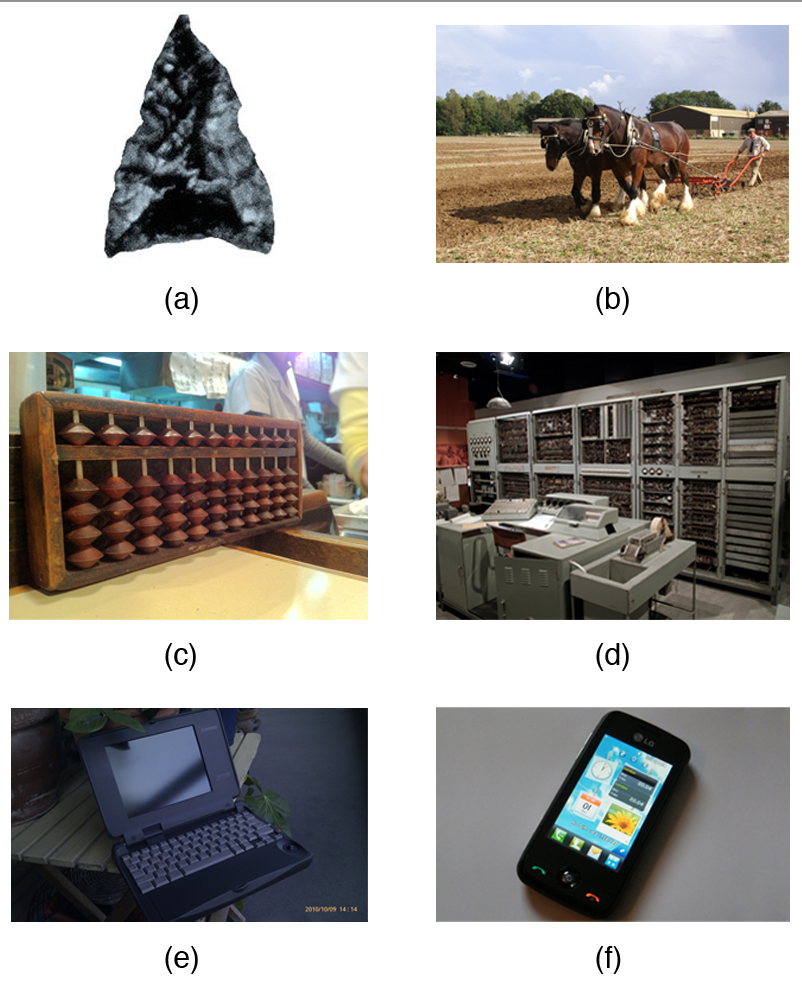

What Is Technology?

While most people probably picture computers and cell phones when the subject of technology comes up, technology is not merely a product of the modern era. For example, fire and stone tools were important forms of technology developed during the Stone Age. Just as the availability of digital technology shapes how we live today, the creation of stone tools changed how premodern humans lived and how well they ate. From the first calculator, invented in 2400 BCE in Babylon in the form of an abacus, to the predecessor of the modern computer, created in 1882 by Charles Babbage, all of our technological innovations are advancements on previous iterations. And indeed, all aspects of our lives today are influenced by technology. In agriculture, the introduction of machines that can till, thresh, plant, and harvest greatly reduced the need for manual labour, which in turn meant there were fewer rural jobs, which led to the urbanization of society, as well as lowered birthrates because there was less need for large families to work the farms. In the criminal justice system, the ability to ascertain innocence through DNA testing has saved the lives of people on death row. The examples are endless: technology plays a role in absolutely every aspect of our lives.

Technological Inequality

As with any improvement to human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster. This technological stratification has led to a new focus on ensuring better access for all.

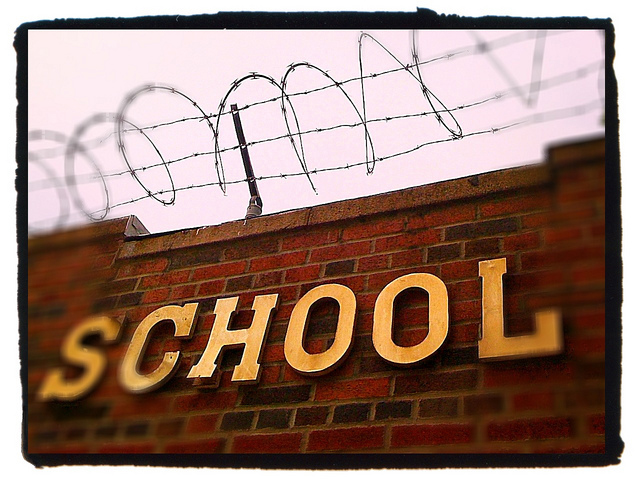

There are two forms of technological stratification. The first is differential class-based access to technology in the form of the digital divide. This digital divide has led to the second form, a knowledge gap, which is, as it sounds, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the digital divide as “the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard to both their opportunities to access information and communication technology (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities.” (OECD, 2001, p.5) For example, students in well-funded schools receive more exposure to technology than students in poorly funded schools. Those students with more exposure gain more proficiency, making them far more marketable in an increasingly technology-based job market, leaving our society divided into those with technological knowledge and those without. Even as we improve access, we have failed to address an increasingly evident gap in e-readiness, the ability to sort through, interpret, and process knowledge (Sciadas, 2003).

Since the beginning of the millennium, social science researchers have tried to bring attention to the digital divide, the uneven access to technology along race, class, and geographic lines. The term became part of the common lexicon in 1996, when then U.S. Vice-President Al Gore used it in a speech. In part, the issue of the digital divide had to do with communities that received infrastructure upgrades that enabled high-speed internet access, upgrades that largely went to affluent urban and suburban areas, leaving out large swaths of the country.

At the end of the 20th century, technology access was also a big part of the school experience for those whose communities could afford it. Early in the millennium, poorer communities had little or no technology access, while well-off families had personal computers at home and wired classrooms in their schools. In Canada we see a clear relationship between youth computer access and use and socioeconomic status in the home. As one study points out, about a third of the youth whose parents have no formal or only elementary school education have no computer in their home compared to 13% of those whose parent has completed high school (Looker and Thiessen, 2003). In the 2000s, however, the prices for low-end computers dropped considerably, and it appeared the digital divide was ending. And while it is true that internet usage, even among those with low annual incomes, continues to grow, it would be overly simplistic to say that the digital divide has been completely resolved.

In fact, new data from the Pew Research Center (2011) suggest the emergence of a new divide. As technological devices gets smaller and more mobile, larger percentages of minority groups are using their phones to connect to the internet. In fact, about 50% of people in these minority groups connect to the web via such devices, whereas only one-third of whites do (Washington, 2011). And while it might seem that the internet is the internet, regardless of how you get there, there is a notable difference. Tasks like updating a résumé or filling out a job application are much harder on a cell phone than on a wired computer in the home. As a result, the digital divide might not mean access to computers or the internet, but rather access to the kind of online technology that allows for empowerment, not just entertainment (Washington, 2011).

Liff and Shepard (2004) found that although the gender digital divide has decreased in the sense of access to technology, it remained in the sense that women, who are accessing technology shaped primarily by male users, feel less confident in their internet skills and have less internet access at both work and home. Finally, Guillen and Suarez (2005) found that the global digital divide resulted from both the economic and sociopolitical characteristics of countries.

Planned Obsolescence: Technology That’s Built to Crash

Chances are your mobile phone company, as well as the makers of your DVD player and MP3 device, are all counting on their products to fail. Not too quickly, of course, or consumers would not stand for it — but frequently enough that you might find that when the built-in battery on your iPod dies, it costs far more to fix it than to replace it with a newer model. Or you find that the phone company emails you to tell you that you’re eligible for a free new phone because yours is a whopping two years old. Appliance repair people say that while they might be fixing some machines that are 20 years old, they generally are not fixing the ones that are seven years old; newer models are built to be thrown out. This is called planned obsolescence, and it is the business practice of planning for a product to be obsolete or unusable from the time it is created (The Economist, 2009).

To some extent, this is a natural extension of new and emerging technologies. After all, who is going to cling to an enormous and slow desktop computer from 2000 when a few hundred dollars can buy one that is significantly faster and better? But the practice is not always so benign. The classic example of planned obsolescence is the nylon stocking. Women’s stockings — once an everyday staple of women’s lives — get “runs” or “ladders” after a few wearings. This requires the stockings to be discarded and new ones purchased. Not surprisingly, the garment industry did not invest heavily in finding a rip-proof fabric; it was in their best interest that their product be regularly replaced.

Those who use Microsoft Windows might feel that they, like the women who purchase endless pairs of stockings, are victims of planned obsolescence. Every time Windows releases a new operating system, there are typically not many changes that consumers feel they must have. However, the software programs are upwardly compatible only. This means that while the new versions can read older files, the old version cannot read the newer ones. Even the ancillary technologies based on operating systems are only compatible upward. In 2014, the Windows XP operating system, off the market for over five years, stopped being supported by Microsoft when in reality is has not been supported by newer printers, scanners, and software add-ons for many years.

Ultimately, whether you are getting rid of your old product because you are being offered a shiny new free one (like the latest smartphone model), or because it costs more to fix than to replace (like an iPod), or because not doing so leaves you out of the loop (like the Windows system), the result is the same. It might just make you nostalgic for your old Sony Walkman and VCR.

But obsolescence gets even more complex. Currently, there is a debate about the true cost of energy consumption for products. This cost would include what is called the embodied energy costs of a product. Embodied energy is the calculation of all the energy costs required for the resource extraction, manufacturing, transportation, marketing, and disposal of a product. One contested claim is that the energy cost of a single cell phone is about 25% of the cost of a new car. We love our personal technology but it comes with a cost. Think about the incredible social organization undertaken from the idea of manufacturing a cell phone through to its disposal after about two years of use (Kedrosky, 2011).

8.2. Media and Technology in Society

Technology and the media are interwoven, and neither can be separated from contemporary society in most developed and developing nations. Media is a term that refers to all print, digital, and electronic means of communication. From the time the printing press was created (and even before), technology has influenced how and where information is shared. Today, it is impossible to discuss media and the ways that societies communicate without addressing the fast-moving pace of technology. Twenty years ago, if you wanted to share news of your baby’s birth or a job promotion, you phoned or wrote letters. You might tell a handful of people, but probably you would not call up several hundred, including your old high school chemistry teacher, to let them know. Now, by tweeting or posting your big news, the circle of communication is wider than ever. Therefore, when we talk about how societies engage with technology we must take media into account, and vice versa.

Technology creates media. The comic book you bought your daughter at the drugstore is a form of media, as is the movie you rented for family night, the internet site you used to order dinner online, the billboard you passed on the way to get that dinner, and the newspaper you read while you were waiting to pick up your order. Without technology, media would not exist; but remember, technology is more than just the media we are exposed to.

Categorizing Technology

There is no one way of dividing technology into categories. Whereas once it might have been simple to classify innovations such as machine-based or drug-based or the like, the interconnected strands of technological development mean that advancement in one area might be replicated in dozens of others. For simplicity’s sake, we will look at how the U.S. Patent Office, which receives patent applications for nearly all major innovations worldwide, addresses patents. This regulatory body will patent three types of innovation. Utility patents are the first type. These are granted for the invention or discovery of any new and useful process, product, or machine, or for a significant improvement to existing technologies. The second type of patent is a design patent. Commonly conferred in architecture and industrial design, this means someone has invented a new and original design for a manufactured product. Plant patents, the final type, recognize the discovery of new plant types that can be asexually reproduced. While genetically modified food is the hot-button issue within this category, farmers have long been creating new hybrids and patenting them. A more modern example might be food giant Monsanto, which patents corn with built-in pesticide (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 2011).

Such evolving patents have created new forms of social organization and disorganization. Efforts by Monsanto to protect its patents have led to serious concerns about who owns the food production system, and who can afford to participate globally in this new agrarian world. This issue was brought to a head in a landmark Canadian court case between Monsanto and Saskatchewan farmer Percy Schmeiser. Schmeiser found Monsanto’s genetically modified “Roundup Ready” canola growing on his farm. He saved the seed and grew his own crop, but Monsanto tried to charge him licensing fees because of their patent. Dubbed a true tale of David versus Goliath, both sides are claiming victory (Mercola, 2011; Monsanto, N.d.). What is important to note is that through the courts, Monsanto established its right to the ownership of its genetically modified seeds even after multiple plantings. Each generation of seeds harvested still belonged to Monsanto. For millions of farmers globally, such a new market model for seeds represents huge costs and dependence on a new and evolving corporate seed supply system.

Anderson and Tushman (1990) suggest an evolutionary model of technological change, in which a breakthrough in one form of technology leads to a number of variations. Once those are assessed, a prototype emerges, and then a period of slight adjustments to the technology, interrupted by a breakthrough. For example, floppy disks were improved and upgraded, then replaced by zip disks, which were in turn improved to the limits of the technology and were then replaced by flash drives. This is essentially a generational model for categorizing technology, in which first-generation technology is a relatively unsophisticated jumping-off point leading to an improved second generation, and so on.

Types of Media and Technology

Media and technology have evolved hand in hand, from early print to modern publications, from radio to television to film. New media emerge constantly, such as we see in the online world.

Print Newspaper

Early forms of print media, found in ancient Rome, were hand-copied onto boards and carried around to keep the citizenry informed. With the invention of the printing press, the way that people shared ideas changed, as information could be mass produced and stored. For the first time, there was a way to spread knowledge and information more efficiently; many credit this development as leading to the Renaissance and ultimately the Age of Enlightenment. This is not to say that newspapers of old were more trustworthy than the Weekly World News and National Enquirer are today. Sensationalism abounded, as did censorship that forbade any subjects that would incite the populace.

The invention of the telegraph, in the mid-1800s, changed print media almost as much as the printing press. Suddenly information could be transmitted in minutes. As the 19th century became the 20th, American publishers such as Hearst redefined the world of print media and wielded an enormous amount of power to socially construct national and world events. Of course, even as the Canadian media empires of Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) and Roy Thomson or the U.S. empires of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were growing, print media also allowed for the dissemination of counter-cultural or revolutionary materials. Internationally, Vladimir Lenin’s Irksa (The Spark) newspaper was published in 1900 and played a role in Russia’s growing communist movement (World Association of Newspapers, 2004).

With the invention and widespread use of television in the mid-20th century, newspaper circulation steadily dropped off, and in the 21st century, circulation has dropped further as more people turn to internet news sites and other forms of new media to stay informed. This shift away from newspapers as a source of information has profound effects on societies. When the news is given to a large diverse conglomerate of people, it must (to appeal to them and keep them subscribing) maintain some level of broad-based reporting and balance. As newspapers decline, news sources become more fractured, so that the audience can choose specifically what it wants to hear and what it wants to avoid. But the real challenge to print newspapers is that revenue sources are declining much faster than circulation is dropping. With an anticipated decline in revenue of over 20% by 2017, the industry is in trouble (Ladurantaye, 2013). Unable to compete with digital media, large and small newspapers are closing their doors across the country. Something to think about is the concept of embodied energy mentioned earlier. The print newspapers are responsible for much of these costs internally. Digital media has downloaded much of these costs onto the consumer through personal technology purchases.

Television and Radio

Radio programming obviously preceded television, but both shaped people’s lives in much the same way. In both cases, information (and entertainment) could be enjoyed at home, with a kind of immediacy and community that newspapers could not offer. Prime Minister Mackenzie King broadcast his radio message out to Canada in 1927. He later used radio to promote economic cooperation in response to the growing socialist agitation against the abuses of capitalism both outside and within Canada (McGivern, 1990).

Radio was the first “live” mass medium. People heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor as it was happening. Hockey Night in Canada was first broadcast live in 1932. Even though people were in their own homes, media allowed them to share these moments in real time. Unlike newspapers, radio is a survivor. As Canada’s globally renowned radio marketing guru Terry O’Reilly asserts, radio survives “because it is such a ‘personal’ medium. Radio is a voice in your ear. It is a highly personal activity.” He also points out that “radio is local. It broadcasts news and programming that is mostly local in nature. And through all the technological changes happening around radio, and in radio, be it AM moving to FM moving to satellite radio and internet radio, basic terrestrial radio survives into another day” (O’Reilly, 2014). This same kind of separate-but-communal approach occurred with other entertainment too. School-aged children and office workers still gather to discuss the previous night’s instalment of a serial television or radio show.

The influence of Canadian television has always reflected a struggle with the influence of U.S. television dominance, the language divide, and strong federal government intervention into the industry for political purposes. There were thousands of televisions in Canada receiving U.S. broadcasting a decade before the first two Canadian stations began broadcasting in 1952 (Wikipedia, N.d.). Public television, in contrast, offered an educational nonprofit alternative to the sensationalization of news spurred by the network competition for viewers and advertising dollars. Those sources — PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) in the United States, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), and CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), which straddled the boundaries of public and private, garnered a worldwide reputation for quality programming and a global perspective. Al Jazeera, the Arabic independent news station, has joined this group as a similar media force that broadcasts to people worldwide.

The impact of television on North American society is hard to overstate. By the late 1990s, 98% of homes had at least one television set. All this television has a powerful socializing effect, with these forms of visual media providing reference groups while reinforcing social norms, values, and beliefs.

Film

The film industry took off in the 1930s, when colour and sound were first integrated into feature films. Like television, early films were unifying for society: As people gathered in theatres to watch new releases, they would laugh, cry, and be scared together. Movies also act as time capsules or cultural touchstones for society. From tough-talking Clint Eastwood to the biopic of Facebook founder and Harvard dropout Mark Zuckerberg, movies illustrate society’s dreams, fears, and experiences. The film industry in Canada has struggled to maintain its identity while at the same time embracing the North American industry by actively competing for U.S. film production in Canada. Today, a significant number of the recognized trades occupations requiring apprenticeship and training are in the film industry. While many North Americans consider Hollywood the epicentre of moviemaking, India’s Bollywood actually produces more films per year, speaking to the cultural aspirations and norms of Indian society.

New Media

New media encompasses all interactive forms of information exchange. These include social networking sites, blogs, podcasts, wikis, and virtual worlds. The list grows almost daily. New media tends to level the playing field in terms of who is constructing it (i.e., creating, publishing, distributing, and accessing information) (Lievrouw and Livingstone, 2006), as well as offering alternative forums to groups unable to gain access to traditional political platforms, such as groups associated with the Arab Spring protests (van de Donk et al., 2004). However, there is no guarantee of the accuracy of the information offered. In fact, the immediacy of new media coupled with the lack of oversight means that we must be more careful than ever to ensure our news is coming from accurate sources.

New media is already redefining information sharing in ways unimaginable even a decade ago. New media giants like Google and Facebook have recently acquired key manufacturers in the aerial drones market creating an exponential ability to reach further in data collecting and dissemination. While the corporate line is benign enough, the implications are much more profound in this largely unregulated arena of aerial monitoring. With claims of furthering remote internet access, “industrial monitoring, scientific research, mapping, communications, and disaster assistance,” the reach is profound (Claburn, 2014). But when aligned with military and national surveillance interests these new technologies become largely exempt from regulations and civilian oversight.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Please “Friend” Me: Students and Social Networking

The phenomenon known as Facebook was designed specifically for students. Whereas earlier generations wrote notes in each other’s printed yearbooks at the end of the academic year, modern technology and the internet ushered in dynamic new ways for people to interact socially. Instead of having to meet up on campus, students can call, text, and Skype from their dorm rooms. Instead of a study group gathering weekly in the library, online forums and chat rooms help learners connect. The availability and immediacy of computer technology has forever changed the ways students engage with each other.

Now, after several social networks have vied for primacy, a few have established their place in the market and some have attracted niche audience. While Facebook launched the social networking trend geared toward teens and young adults, now people of all ages are actively “friending” each other. LinkedIn distinguished itself by focusing on professional connections, serving as a virtual world for workplace networking. Newer offshoots like Foursquare help people connect based on the real-world places they frequent, while Twitter has cornered the market on brevity.

These newer modes of social interaction have also spawned questionable consequences, such as cyberbullying and what some call FAD, or Facebook addiction disorder. In an international study of smartphone users aged 18 to 30, 60% say they are “compulsive” about checking their smartphones and 42% admit to feeling “anxious” when disconnected; 75% check their smartphones in bed; more than 33% check them in the bathroom and 46% email and check social media while eating (Cisco, 2012). An International Data Corporation (IDC) study of 7,446 smartphone users aged 18 to 44 in the United States in 2012 found that:

- Half of the U.S. population have smartphones and of those 70% use Facebook. Using Facebook is the third most common smartphone activity, behind email (78%) and web browsing (73%).

- 61% of smartphone users check Facebook every day.

- 62% of smartphone users check their device first thing on waking up in the morning and 79% check within 15 minutes. Among 18-to-24-year-olds the figures are 74% and 89%, respectively.

- Smartphone users check Facebook approximately 14 times a day.

- 84% of the time using smartphones is spent on texting, emailing and using social media like Facebook, whereas only 16% of the time is spent on phone calls. People spend an average of 132 minutes a day on their smartphones including 33 minutes on Facebook.

- People use Facebook throughout the day, even in places where they are not supposed to: 46% use Facebook while doing errands and shopping; 47% when they are eating out; 48% while working out; 46% in meetings or class; and 50% while at the movies.

The study noted that the dominant feeling the survey group reported was “a sense of feeling connected” (IDC, 2012). Yet, in the international study cited above, two-thirds of 18- to 30-year-old smartphone users said they spend more time with friends online than they do in person.

All of these social networks demonstrate emerging ways that people interact, whether positive or negative. Sociologists ask whether there might be long-term effects of replacing face-to-face interaction with social media. In an interview on the Conan O’Brian Show that ironically circulated widely through social media, the comedian Louis CK described the use of smartphones as “toxic.” They do not allow for children who use them to build skills of empathy because the children do not interact face to face, or see the effects their comments have on others. Moreover, he argues, they do not allow people to be alone with their feelings. “The thing is, you need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away” (NewsComAu, 2013). What do you think? How do social media like Facebook and communication technologies like smartphones change the way we communicate? How could this question be studied?

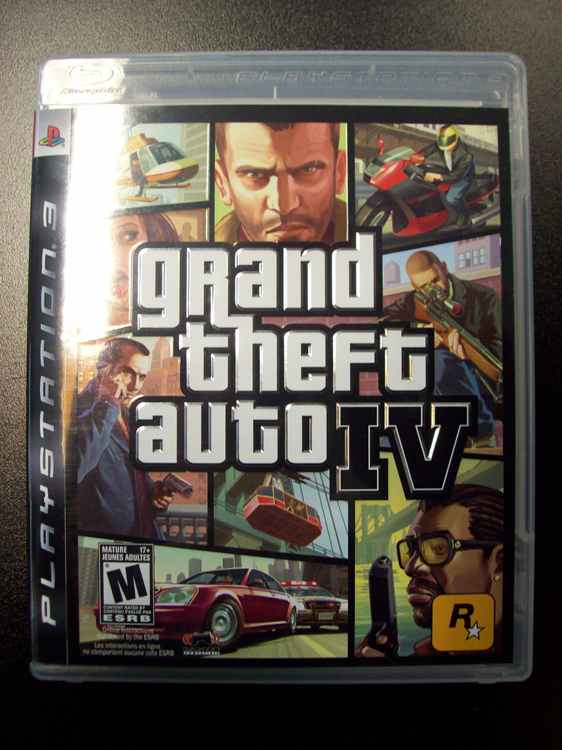

Violence in Media and Video Games: Does It Matter?

A glance through popular video game and movie titles geared toward children and teens shows the vast spectrum of violence that is displayed, condoned, and acted out. It may hearken back to Popeye and Bluto beating up on each other, or Wile E. Coyote trying to kill and devour the Road Runner, but the graphics and actions have moved far beyond Acme’s cartoon dynamite.

As a way to guide parents in their programming choices, the motion picture industry put a rating system in place in the 1960s. But new media — video games in particular — proved to be uncharted territory. In 1994, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) set a ratings system for games that addressed issues of violence, sexuality, drug use, and the like. California took it a step further by making it illegal to sell video games to underage buyers. The case led to a heated debate about personal freedoms and child protection, and in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the California law, stating it violated freedom of speech (ProCon, 2012).

With somewhat more muted responses to claims of violations of freedoms, the Canadian rating system through provincial regulation reflects the diversity of interests in connecting media to cultural interests. With the exception of Quebec, most provinces tend to follow the voluntary Canadian Home Video Ratings System established by the Motion Picture Industry-Canada. Quebec has developed internal legislation and policies for motion picture distribution.

Children’s play has often involved games of aggression — from soldiers at war, to cops and robbers, to water-balloon fights at birthday parties. Many articles report on the controversy surrounding the linkage between violent video games and violent behaviour. Are these charges true? Psychologists Anderson and Bushman (2001) reviewed 40-plus years of research on the subject and, in 2003, determined that there are causal linkages between violent video game use and aggression. They found that children who had just played a violent video game demonstrated an immediate increase in hostile or aggressive thoughts, an increase in aggressive emotions, and physiological arousal that increased the chances of acting out aggressive behaviour (Anderson, 2003).

Ultimately, repeated exposure to this kind of violence leads to increased expectations regarding violence as a solution, increased violent behavioural scripts, and making violent behaviour more cognitively accessible (Anderson, 2003). In short, people who play a lot of these games find it easier to imagine and access violent solutions than nonviolent ones, and are less socialized to see violence as a negative. While these facts do not mean there is no role for video games, it should give players pause. Clearly, when it comes to violence in gaming, it’s not “only a game.”

Product Advertising

Companies use advertising to sell to us, but the way they reach us is changing. Increasingly, synergistic advertising practices ensure you are receiving the same message from a variety of sources. For example, you may see billboards for Molson’s on your way to a stadium, sit down to watch a game preceded by a beer commercial on the big screen, and watch a halftime ad in which people are frequently shown holding up the trademark bottles. Chances are you can guess which brand of beer is for sale at the concession stand.

Advertising has changed, as technology and media have allowed consumers to bypass traditional advertising venues. From the invention of the remote control, which allows us to ignore television advertising without leaving our seats, to recording devices that let us watch television programs but skip the ads, conventional advertising is on the wane. And print media is no different. As mentioned earlier, advertising revenue in newspapers and on television have fallen significantly showing that companies need new ways of getting their message to consumers.

With Google alone earning over US$55 billion a year in revenue, the big players in new media are responding in innovative ways (Google Investor Relations, 2014). This interest from media makes sense when you consider that subscribers pay over $40 each for pay-per-click keywords such as “insurance,” “loans,” and “mortgages” (Wordstream, N.d.). Today, Google alone earns over 50% of the mobile device revenue generated worldwide (Google Investor Relations, 2014).

What is needed for successful new media marketing is research. In Canada, market research is valued at almost a billion dollars a year, in an industry employing over 1,800 professional research practitioners with a strong professional association. From market segmentation research to online focus groups, meta-data analysis to crowdsourcing, market research has embraced new media to create winning and profitable revenue streams for web-based corporations. (MRIA-ARIM, N.d.) As an aside, researchers trained in the social sciences, including sociology are well represented with successful careers in this industry (the author is a Certified Marketing Research Professional with the MRIA).

8.3. Global Implications

Technology, and increasingly media, has always driven globalization. Thomas Friedman (2005), in a landmark study, identified several ways in which technology “flattened” the globe and contributed to our global economy. The first edition of The World Is Flat, written in 2005, posits that core economic concepts were changed by personal computing and high-speed internet. Access to these two technological shifts has allowed core-nation corporations to recruit workers in call centres located in China or India. Using examples like a Midwestern American woman who runs a business from her home via the call centres of Bangalore, India, Friedman warns that this new world order will exist whether core-nation businesses are ready or not, and that in order to keep its key economic role in the world, North America will need to pay attention to how it prepares workers of the 21st century for this dynamic.

Of course not everyone agrees with Friedman’s theory. Many economists pointed out that, in reality, innovation, economic activity, and population still gather in geographically attractive areas, continuing to create economic peaks and valleys, which are by no means flattened out to mean equality for all. China’s hugely innovative and powerful cities of Shanghai and Beijing are worlds away from the rural squalour of the country’s poorest denizens.

It is worth noting that Friedman is an economist, not a sociologist. His work focuses on the economic gains and risks this new world order entails. In this section, we will look more closely at how media globalization and technological globalization play out in a sociological perspective. As the names suggest, media globalization is the worldwide integration of media through the cross-cultural exchange of ideas, while technological globalization refers to the cross-cultural development and exchange of technology.

Media Globalization

Lyons (2005) suggests that multinational corporations are the primary vehicle of media globalization. These corporations control global mass-media content and distribution (Compaine, 2005). It is true, when looking at who controls which media outlets, that there are fewer independent news sources as larger and larger conglomerates develop.

On the surface, there is endless opportunity to find diverse media outlets. But the numbers are misleading. Mass media control and ownership is highly concentrated in Canada. Bell, Telus, and Rogers control over 80% of the wireless and internet service provider market; 70% of the daily and community newspapers are owned by seven corporations; and 10 companies control over 80% of the private sector radio and television market (CMCRP, N.d.; Newspapers Canada, 2013). As was pointed out in a Parliamentary report in 2012, an example of increased vertical control is a company that “might own a broadcast distributor (Rogers Cable), conventional television stations, pay and specialty television channels, and even the content for its broadcasters (Rogers owns the Toronto Blue Jays, whose games are shown on conventional and pay and specialty television channels)” (Theckedath and Thomas, 2012).

While some social scientists predicted that the increase in media forms would break down geographical barriers and create a global village (McLuhan, 1964), current research suggests that the public sphere accessing the global village will tend to be rich, Caucasian, and English-speaking (Jan, 2009). As shown by the spring 2011 uprisings throughout the Arab world, technology really does offer a window into the news of the world. For example, here in the West we saw internet updates of Egyptian events in real time, with people tweeting, posting, and blogging on the ground in Tahrir Square.

Still, there is no question that the exchange of technology from core nations to peripheral and semi-peripheral ones leads to a number of complex issues. For instance, someone using a critical sociology approach might focus on how much political ideology and cultural colonialism occurs with technological growth. In theory at least, technological innovations are ideology-free; a fibre optic cable is the same in a Muslim country as a secular one, in a communist country or a capitalist one. But those who bring technology to less developed nations — whether they are nongovernment organizations, businesses, or governments — usually have an agenda. A functionalist, in contrast, might focus on how technology creates new ways to share information about successful crop-growing programs, or on the economic benefits of opening a new market for cell phone use. Interpretive sociologists might emphasize the way in which the global exchange of views creates the possibility of mutual understanding and consensus. In each case, there are cultural and societal assumptions and norms being delivered along with those high-speed connections.

Cultural and ideological biases are not the only risks of media globalization. In addition to the risk of cultural imperialism and the loss of local culture, other problems come with the benefits of a more interconnected globe. One risk is the potential censoring by national governments that let in only the information and media they feel serves their message, as can be seen in China. In addition, core nations such as Canada have seen the use of international media such as the internet circumvent local laws against socially deviant and dangerous behaviours such as gambling, child pornography, and the sex trade. Offshore or international websites allow citizens to seek out whatever illegal or illicit information they want, from 24-hour online gambling sites that do not require proof of age, to sites that sell child pornography. These examples illustrate the societal risks of unfettered information flow.

China and the Internet: An Uncomfortable Friendship

Today, the internet is used to access illegal gambling and pornography sites, as well as to research stocks, crowd-source what car to buy, or keep in touch with childhood friends. Can we allow one or more of those activities, while restricting the rest? And who decides what needs restricting? In a country with democratic principles and an underlying belief in free-market capitalism, the answer is decided in the court system. But globally, the questions — and the government’s responses — are very different.

China is in many ways the global poster child for the uncomfortable relationship between internet freedom and government control. A country with a tight rein on the dissemination of information, China has long worked to suppress what it calls “harmful information,” including dissent concerning government politics, dialogue about China’s role in Tibet, or criticism of the government’s handling of events.

With sites like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube blocked in China, the nation’s internet users — some 500 million strong in 2011 — turn to local media companies for their needs. Renren.com is China’s answer to Facebook. Perhaps more importantly from a social-change perspective, Sina Weibo is China’s version of Twitter. Microblogging, or weibo, acts like Twitter in that users can post short messages that can be read by their subscribers. And because these services move so quickly and with such wide scope, it is difficult for government overseers to keep up. This tool was used to criticize government response to a deadly rail crash and to protest a chemical plant. It was also credited with the government’s decision to report more accurately on the air pollution in Beijing, which occurred after a high-profile campaign by a well-known property developer (Pierson, 2012).

There is no question of China’s authoritarian government ruling over this new form of internet communication. The nation blocks the use of certain terms, such as “human rights,” and passes new laws that require people to register with their real names, making it more dangerous to criticize government actions. Indeed, 56-year-old microblogger Wang Lihong was sentenced to nine months in prison for “stirring up trouble,” as her government described her work helping people with government grievances (Bristow, 2011). But the government cannot shut down this flow of information completely. Foreign companies, seeking to engage with the increasingly important Chinese consumer market, have their own accounts: the NBA has more than 5 million followers, and probably the most famous foreigner in China, Canadian comedian and Order of Canada recipient Mark Rowswell boasts almost 3 million Weibo followers (2014). The government, too, uses Weibo to get its own message across. As the years progress, the rest of the world anxiously watches China’s approach to social media and the freedoms it offers — on Sina Weibo and beyond — by the rest of the world.

Technological Globalization

Technological globalization is impacted in large part by technological diffusion, the spread of technology across borders. In the last two decades, there has been rapid improvement in the spread of technology to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations, and a 2008 World Bank report discusses both the benefits and ongoing challenges of this diffusion. In general, the report found that technological progress and economic growth rates were linked, and that the rise in technological progress has helped improve the situations of many living in absolute poverty (World Bank, 2008). The report recognizes that rural and low-tech products such as corn can benefit from new technological innovations, and that, conversely, technologies like mobile banking can aid those whose rural existence consists of low-tech market vending. In addition, technological advances in areas like mobile phones can lead to competition, lowered prices, and concurrent improvements in related areas such as mobile banking and information sharing.

However, the same patterns of social inequality that create a digital divide in the West also create digital divides in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. While the growth of technology use among countries has increased dramatically over the past several decades, the spread of technology within countries is significantly slower among peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. In these countries, far fewer people have the training and skills to take advantage of new technology, let alone access it. Technological access tends to be clustered around urban areas, leaving out vast swaths of peripheral-nation citizens. While the diffusion of information technologies has the potential to resolve many global social problems, it is often the population most in need that is most affected by the digital divide. For example, technology to purify water could save many lives, but the villages in peripheral nations most in need of water purification don’t have access to the technology, the funds to purchase it, or the technological comfort level to introduce it as a solution.

The Mighty Cell Phone: How Mobile Phones Are Impacting Sub-Saharan Africa

In many of Africa’s poorest countries there is a marked lack of infrastructure. Bad roads, limited electricity, minimal schools — the list goes on. Access to telephones has long been on that list. But while landline access has not changed appreciably during the past 10 years, there’s been a marked fivefold increase in mobile phone access; more than a third of people in sub-Saharan Africa have the ability to access a mobile phone (Katine, 2010). Even more can access a “village phone” — a shared phone program created by the Grameen Foundation. With access to mobile phone technology, a host of benefits are available that have the potential to change the dynamics in these poorest nations. Sometimes that change is as simple as being able to make a phone call to neighbouring market towns. By finding out which markets have vendors interested in their goods, fishers and farmers can ensure they travel to the market that will serve them best, avoiding a wasted trip. Others can use mobile phones and some of the emerging money-sending systems to securely send money from one place to a family member or business partner elsewhere (Katine, 2010).

These programs are often funded by businesses like Germany’s Vodafone or Britain’s Masbabi, which hope to gain market share in the region. Phone giant Nokia points out that worldwide there are 4 billion mobile phone users — that’s more than twice as many bank accounts that exist — meaning there is ripe opportunity to connect banking companies with people who need their services (ITU News, 2009). Not all access is corporate-based, however. Other programs are funded by business organizations that seek to help peripheral nations with tools for innovation and entrepreneurship.

But this wave of innovation and potential business comes with costs. There is, certainly, the risk of cultural imperialism, and the assumption that core nations (and core-nation multinationals) know what is best for those struggling in the world’s poorest communities. Whether well intentioned or not, the vision of a continent of Africans successfully chatting on their iPhone may not be ideal. As with all aspects of global inequity, technology in Africa requires more than just foreign investment. There must be a concerted effort to ensure the benefits of technology get to where they are needed most.

8.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

It is difficult to conceive of any one theory or theoretical perspective that can explain the variety of ways that people interact with technology and the media. Technology runs the gamut from the match you strike to light a candle all the way up to sophisticated nuclear power plants that might power the factory where that candle was made. Media could refer to the television you watch, the ads wrapping the bus you take to work or school, or the magazines you flip through in a waiting room, not to mention all the forms of new media, including Twitter, Facebook, blogs, YouTube, and the like. Are media and technology critical to the forward march of humanity? Are they pernicious capitalist tools that lead to the exploitation of workers worldwide? Are they the magic bullet the world has been waiting for to level the playing field and raise the world’s poor out of extreme poverty? Each perspective generates understandings of technology and media that help us examine the way our lives are affected.

Structural Functionalism

Because functionalism focuses on how media and technology contribute to the smooth functioning of society, a good place to begin understanding this perspective is to write a list of functions you perceive media and technology to perform. Your list might include the ability to find information on the internet, television’s entertainment value, or how advertising and product placement contribute to social norms.

Commercial Function

As you might guess, with nearly every U.S. household possessing a television, and the 250 billion hours of television watched annually by Americans, companies that wish to connect with consumers find television an irresistible platform to promote their goods and services (Nielsen Wire, 2011). Television advertising is a highly functional way to meet a market demographic where it lives. Sponsors can use the sophisticated data gathered by network and cable television companies regarding their viewers and target their advertising accordingly.

It certainly doesn’t stop with television. Commercial advertising precedes movies in theatres and shows up on and inside of public transportation, as well as on the sides of buildings and roadways. Major corporations such as Coca-Cola bring their advertising into public schools, sponsoring sports fields or tournaments, as well as filling the halls and cafeterias of those schools with vending machines hawking their goods. With the rising concerns about childhood obesity and attendant diseases, the era of pop machines in schools may be numbered. But not to worry. Coca-Cola’s filtered tap water, Dasani, and its juice products will remain standards in many schools.

Entertainment Function

An obvious manifest function of media is its entertainment value. Most people, when asked why they watch television or go to the movies, would answer that they enjoy it. Within the 98% of households that have a TV, the amount of time spent watching is substantial, with the average adult Canadian viewing time of 30 hours a week (TVB, 2014). Clearly, enjoyment is paramount. On the technology side, as well, there is a clear entertainment factor to the use of new innovations. From online gaming to chatting with friends on Facebook, technology offers new and more exciting ways for people to entertain themselves.

Social Norm Functions

Even while the media is selling us goods and entertaining us, it also serves to socialize us, helping us pass along norms, values, and beliefs to the next generation. In fact, we are socialized and resocialized by media throughout our life course. All forms of media teach us what is good and desirable, how we should speak, how we should behave, and how we should react to events. Media also provide us with cultural touchstones during events of national significance. How many of your older relatives can recall watching the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger on television? How many of those reading this textbook followed the events of September 11 or Hurricane Katrina on the television or internet?

But debate exists over the extent and impact of media socialization. Krahe and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that violent media content has a desensitizing affect and is correlated with aggressive thoughts. Another group of scholars (Gentile, Mathieson, and Crick, 2011) found that among children, exposure to media violence led to an increase in both physical and relational aggression. Yet, a meta-analysis study covering four decades of research (Savage, 2003) could not establish a definitive link between viewing violence and committing criminal violence.

It is clear from watching people emulate the styles of dress and talk that appear in media that media has a socializing influence. What is not clear, despite nearly 50 years of empirical research, is how much socializing influence the media has when compared to other agents of socialization, which include any social institution that passes along norms, values, and beliefs (such as peers, family, religious institutions, and the like).

Life-Changing Functions

Like media, many forms of technology do indeed entertain us, provide a venue for commercialization, and socialize us. For example, some studies suggest the rising obesity rate is correlated with the decrease in physical activity caused by an increase in use of some forms of technology, a latent function of the prevalence of media in society (Kautiainen et al., 2005). Without a doubt, a manifest function of technology is to change our lives, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. Think of how the digital age has improved the ways we communicate. Have you ever used Skype or another webcast to talk to a friend or family member far away? Or maybe you have organized a fund drive, raising thousands of dollars, all from your desk chair.

Of course, the downside to this ongoing information flow is the near impossibility of disconnecting from technology, leading to an expectation of constant convenient access to information and people. Such a fast-paced dynamic is not always to our benefit. Some sociologists assert that this level of media exposure leads to narcotizing dysfunction, a term that describes when people are too overwhelmed with media input to really care about the issue, so their involvement becomes defined by awareness instead of by action about the issue at hand (Lazerfeld and Merton, 1948).

Critical Sociology

In contrast to theories in the functional perspective, the critical perspective focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality — social processes that tend to disrupt society rather than contribute to its smooth operation. When taking a critical perspective, one major focus is the differential access to media and technology embodied in the digital divide. Critical sociologists also look at who controls the media, and how media promotes the norms of upper-middle-class white demographics while minimizing the presence of the working class, especially people of colour.

Control of Media and Technology

Powerful individuals and social institutions have a great deal of influence over which forms of technology are released, when and where they are released, and what kind of media is available for our consumption, a form of gatekeeping. Shoemaker and Voss (2009) define gatekeeping as the sorting process by which thousands of possible messages are shaped into a mass media–appropriate form and reduced to a manageable amount. In other words, the people in charge of the media decide what the public is exposed to, which, as C. Wright Mills (1956) famously noted, is the heart of media’s power. Take a moment to think of the way that “new media” evolves and replaces traditional forms of hegemonic media. With a hegemonic media, culturally diverse society can be dominated by one race, gender, or class through the manipulation of the media imposing its worldview as a societal norm. New media renders the gatekeeper role less of a factor in information distribution. Popular sites such as YouTube and Facebook engage in a form of democratized self-policing. Users are encouraged to report inappropriate behaviour that moderators will then address.

In addition, some conflict theorists suggest that the way North American media is generated results in an unbalanced political arena. Those with the most money can buy the most media exposure, run smear campaigns against their competitors, and maximize their visual presence. The Conservative Party began running attack ads on Justin Trudeau moments after his acceptance speech on winning the leadership of the Liberal Party in 2013. It is difficult to avoid the Enbridge and Cenovus advertisements that promote their controversial Northern Gateway pipeline and tar sands projects. What do you think a critical perspective theorist would suggest about the potential for the non-rich to be heard in politics?

Technological Social Control and Digital Surveillance

Social scientists take the idea of the surveillance society so seriously that there is an entire journal devoted to its study, Surveillance and Society. The panoptic surveillance envisioned by Jeremy Bentham and later analyzed by Michel Foucault (1975) is increasingly realized in the form of technology used to monitor our every move. This surveillance was imagined as a form of complete visibility and constant monitoring in which the observation posts are centralized and the observed are never communicated with directly. Today, digital security cameras capture our movements, observers can track us through our cell phones, and police forces around the world use facial-recognition software.

Feminist Perspective

Take a look at popular television shows, advertising campaigns, and online game sites. In most, women are portrayed in a particular set of parameters and tend to have a uniform look that society recognizes as attractive. Most are thin, white or light-skinned, beautiful, and young. Why does this matter? Feminist perspective theorists believe it is crucial in creating and reinforcing stereotypes. For example, Fox and Bailenson (2009) found that online female avatars (the characters you play in online games like World of Warcraft or Second Life) conforming to gender stereotypes enhances negative attitudes toward women, and Brasted (2010) found that media (advertising in particular) promotes gender stereotypes.

The gender gap in tech-related fields (science, technology, engineering, and math) is no secret. A 2011 U.S. Department of Commerce report suggested that gender stereotyping is one reason for this gap, acknowledging the bias toward men as keepers of technological knowledge (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2011). But gender stereotypes go far beyond the use of technology. Press coverage in the media reinforces stereotypes that subordinate women, giving airtime to looks over skills, and disparaging women who defy accepted norms.

Recent research in new media has offered a mixed picture of its potential to equalize the status of men and women in the arenas of technology and public discourse. A European agency, the Advisory Committee on Equal Opportunities for Men and Women (2010), issued an opinion report suggesting that while there is the potential for new media forms to perpetuate gender stereotypes and the gender gap in technology and media access, at the same time new media could offer alternative forums for feminist groups and the exchange of feminist ideas. Still, the committee warned against the relatively unregulated environment of new media and the potential for antifeminist activities, from pornography to human trafficking, to flourish there.

Increasingly prominent in the discussion of new media and feminism is cyberfeminism, the application to, and promotion of, feminism online. Research on cyberfeminism runs the gamut from the liberating use of blogs by women living in Iraq during the second Gulf War (Pierce, 2011) to the analysis of postmodern discourse on the relationship between the body and technology (Kerr, 2014).

Symbolic Interactionism

Technology itself may act as a symbol for many. The kind of computer you own, the kind of car you drive, whether or not you can afford the latest Apple product — these serve as a social indicator of wealth and status. Neo-Luddites are people who see technology as symbolizing the coldness and alienation of modern life. But for technophiles, technology symbolizes the potential for a brighter future. For those adopting an ideological middle ground, technology might symbolize status (in the form of a massive flat-screen television) or failure (in owning a basic old mobile phone with no bells or whistles).

Social Construction of Reality

Meanwhile, media create and spread symbols that become the basis for our shared understanding of society. Theorists working in the interactionist perspective focus on this social construction of reality, an ongoing process in which people subjectively create and understand reality. Media constructs our reality in a number of ways. For some, the people they watch on a screen can become a primary group, meaning the small informal groups of people who are closest to them. For many others, media becomes a reference group: a group that influences an individual and to which an individual compares himself or herself, and by which we judge our successes and failures. We might do very well without an Android smartphone, until we see characters using it on our favourite television show or our classmates whipping one out between classes.

While media may indeed be the medium to spread the message of the rich white males, Gamson, Croteau, Hoynes, and Sasson (1992) point out that some forms of media discourse allow the appearance of competing constructions of reality. For example, advertisers find new and creative ways to sell us products we do not need and probably would not want without their prompting, but some networking sites such as Freecycle offer a commercial-free way of requesting and trading items that would otherwise be discarded. Additionally, the web is full of blogs chronicling lives lived “off the grid,” or without participation in the commercial economy.

Social Networking and Social Construction

While Twitter and Facebook encourage us to check in and provide details of our day through online social networks, corporations can just as easily promote their products on these sites. Even supposedly crowd-sourced sites like Yelp (which aggregates local reviews) are not immune to corporate shenanigans. That is, we think we are reading objective observations when in reality we may be buying into one more form of advertising.

Facebook, which started as a free social network for college students, is increasingly a monetized business, selling you goods and services in subtle ways. But chances are you do not think of Facebook as one big online advertisement. What started out as a symbol of coolness and insider status, unavailable and inaccessible to parents and corporate shills, now promotes consumerism in the form of games and fandom. For example, think of all the money spent to upgrade popular Facebook games like Farmville.

Notice that whenever you become a “fan,” you likely receive product updates and special deals that promote online and real-world consumerism. It is unlikely that millions of people want to be “friends” with Pampers. But if it means a weekly coupon, they will, in essence, rent out space on their Facebook page for Pampers to appear. Thus, we develop both new ways to spend money and brand loyalties that will last even after Facebook is considered outdated and obsolete. What cannot be forgotten with new technology is the dynamic tension between the liberating effects of these technologies in democratizing information access and flow, and the newly emerging corporate ownership and revenue models that necessitate control of the same technologies.

Key Terms

cyberfeminism: Application to and promotion of feminism online.

design patents: Patents that are granted when someone has invented a new and original design for a manufactured product.

digital divide: The uneven access to technology around race, class, and geographic lines.

e-readiness: The ability to sort through, interpret, and process digital knowledge.

embodied energy: The sum of energy required for a finished product including the resource extraction, transportation, manufacturing, distribution, marketing, and disposal.

evolutionary model of technological change: A breakthrough in one form of technology that leads to a number of variations, from which a prototype emerges, followed by a period of slight adjustments to the technology, interrupted by a breakthrough.

gatekeeping: The sorting process by which thousands of possible messages are shaped into a mass media–appropriate form and reduced to a manageable amount.

knowledge gap: The gap in information that builds as groups grow up without access to technology.

media: All print, digital, and electronic means of communication.

media globalization: The worldwide integration of media through the cross-cultural exchange of ideas.

misogyny: Personal, social, and cultural manifestations of the hatred of girls and women.

narcotizing dysfunction: When people are too overwhelmed with media input to really care about the issue, so their involvement becomes defined by awareness instead of by action about the issue at hand.

neo-Luddites: Those who see technology as a symbol of the coldness of modern life.

new media: All interactive forms of information exchange.

panoptic surveillance: A form of constant monitoring in which the observation posts are decentralized and the observed is never communicated with directly.

planned obsolescence: When a technology company plans for a product to be obsolete or unable to be repaired from the time it’s created.

plant patents: Patents that recognize the discovery of new plant types that can be asexually reproduced.

technological diffusion: The spread of technology across borders.

technological globalization: The cross-cultural development and exchange of technology.

technology: The application of science to solve problems in daily life.

technophiles: Those who see technology as symbolizing the potential for a brighter future.

utility patents: Patents that are granted for the invention or discovery of any new and useful process, product, or machine.

Section Summary

8.1. Technology Today

Technology is the application of science to address the problems of daily life. The fast pace of technological advancement means the advancements are continuous, but that not everyone has equal access. The gap created by this unequal access has been termed the digital divide. The knowledge gap refers to an effect of the “digital divide”: the lack of knowledge or information that keeps those who were not exposed to technology from gaining marketable skills

8.2. Media and Technology in Society

Media and technology have been interwoven from the earliest days of human communication. The printing press, the telegraph, and the internet are all examples of their intersection. Mass media has allowed for more shared social experiences, but new media now creates a seemingly endless amount of airtime for any and every voice that wants to be heard. Advertising has also changed with technology. New media allows consumers to bypass traditional advertising venues, causing companies to be more innovative and intrusive as they try to gain our attention.

8.3. Global Implications

Technology drives globalization, but what that means can be hard to decipher. While some economists see technological advances leading to a more level playing field where anyone anywhere can be a global contender, the reality is that opportunity still clusters in geographically advantaged areas. Still, technological diffusion has led to the spread of more and more technology across borders into peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. However, true technological global equality is a long way off.

8.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

There are myriad theories about how society, technology, and media will progress. Functionalism sees the contribution that technology and media provide to the stability of society, from facilitating leisure time to increasing productivity. Conflict theorists are more concerned with how technology reinforces inequalities among communities, both within and among countries. They also look at how media typically give voice to the most powerful, and how new media might offer tools to help those who are disenfranchised. Symbolic interactionists see the symbolic uses of technology as signs of everything from a sterile futuristic world to a successful professional life.

Section Quiz

1. Jerome is able to use the internet to select reliable sources for his research paper, but Charlie just copies large pieces of web pages and pastes them into his paper. Jerome has _____________ while Charlie does not.

- A functional perspective

- The knowledge gap

- E-readiness

- A digital divide

2. The ________ can be directly attributed to the digital divide, because differential ability to access the internet leads directly to a differential ability to use the knowledge found on the internet.

- Digital divide

- Knowledge gap

- Feminist perspective

- E-gap

3. The fact that your cell phone is using outdated technology within a year or two of purchase is an example of ____________.

- The conflict perspective

- Conspicuous consumption

- Media

- Planned obsolescence

4. The history of technology began _________.

- In the early stages of human societies

- With the invention of the computer

- During the Renaissance

- During the 19th century

8.2. Media and Technology in Society

5. When it comes to technology, media, and society, which of the following is true?

- Media influences technology, but not society.

- Technology created media, but society has nothing to do with these.

- Technology, media, and society are bound and cannot be separated.

- Society influences media but is not connected to technology.

6. If the U.S. Patent Office were to issue a patent for a new type of tomato that tastes like a jellybean, it would be issuing a _________ patent?

- Utility

- Plant

- Design

- The U.S. Patent Office does not issue a patent for plants.

7. Which of the following is the primary component of the evolutionary model of technological change?

- Technology should not be subject to patenting.

- Technology and the media evolve together.

- Technology can be traced back to the early stages of human society.

- A breakthrough in one form of technology leads to a number of variations, and technological developments.

8. Which of the following is not a form of new media?

- A cable television program

- Wikipedia

- A cooking blog

9. Research regarding video game violence suggests that ______________________________.

- Boys who play violent video games become more aggressive, but girls do not

- Girls who play violent video games become more aggressive, but boys do not

- Violent video games have no connection to aggressive behaviour

- Violent video games lead to an increase in aggressive thought and behaviour

10. Comic books, Wikipedia, MTV, and a commercial for Coca-Cola are all examples of:

- Media

- Symbolic interaction perspective

- E-readiness

- The digital divide

8.3. Global Implications

11. When Japanese scientists develop a new vaccine for swine flu and offer that technology to American pharmaceutical companies, __________ has taken place.

- Media globalization

- Technological diffusion

- Monetizing

- Planned obsolescence

12. In the mid-90s, the U.S. government grew concerned that Microsoft was a _______________, exercising disproportionate control over the available choices and prices of computers.

- Monopoly

- Conglomerate

- Functionalism

- Technological globalization

13. The movie Babel featured an international cast and was filmed on location in various nations. When it screened in theatres worldwide, it introduced a number of ideas and philosophies about cross-cultural connections. This might be an example of _______________.

- Technology

- Conglomerating

- Symbolic interaction

- Media globalization

14. Which of the following is not a risk of media globalization?

- The creation of cultural and ideological biases

- The creation of local monopolies

- The risk of cultural imperialism

- The loss of local culture

15. The government of __________ blocks citizens’ access to popular new media sites like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter.

- China

- India

- Afghanistan

- Australia

8.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

16. A parent secretly monitoring the babysitter through the use of GPS, site blocker, and nanny cam is a good example of _______________.

- The social construction of reality

- Technophilia

- A neo-Luddite

- Panoptic surveillance

17. The use of Facebook to create an online persona by only posting images that match your ideal self exemplifies the_____________ that can occur in forms of new media.

- Social construction of reality

- Cyberfeminism

- Market segmentation

- Referencing

18. _________ tend to be more pro-technology, while _______ view technology as a symbol of the coldness of modern life.

- Neo-Luddites; technophiles

- Technophiles; neo-Luddites

- Cyberfeminists; technophiles

- Liberal feminists; conflict theorists

19. When it comes to media and technology, a functionalist would focus on ___________________________.

- The symbols created and reproduced by the media

- The association of technology and technological skill with men

- The way that various forms of media socialize users

- The digital divide between the technological haves and have-nots

20. When all media sources report a simplified version of the environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing, with no effort to convey the hard science and complicated statistical data behind the story, ___________ is probably occurring.

- Gatekeeping

- The digital divide

- Technophilia

- Market segmentation

Short Answer

- Can you think of people in your own life who support or defy the premise that access to technology leads to greater opportunities? How have you noticed technology use and opportunity to be linked, or does your experience contradict this idea?

- Should a government be responsible for providing all citizens with access to the internet? Or is gaining internet access an individual responsibility?

- How has digital media changed social interactions? Do you believe it has deepened or weakened human connections? Defend your answer.

- Conduct sociological research. Google yourself. How much information about you is available to the public? How many and what types of companies offer private information about you for a fee? Compile the data and statistics you find. Write a paragraph or two about the social issues and behaviours you notice.

8.2. Media and Technology in Society

- Where and how do you get your news? Do you watch network television? Read the newspaper? Go online? How about your parents or grandparents? Do you think it matters where you seek out information? Why or why not?

- Do you believe new media allows for the kind of unifying moments that television and radio programming used to? If so, give an example.

- Where are you most likely to notice advertisements? What causes them to catch your attention?

- Do you believe that technology has indeed flattened the world in terms of providing opportunity? Why or why not? Give examples to support your reason.

- Where do you get your news? Is it owned by a large conglomerate (you can do a web search and find out!)? Does it matter to you who owns your local news outlets? Why or why not?

- Who do you think is most likely to bring innovation and technology (like cell phone businesses) to sub-Saharan Africa: nonprofit organizations, governments, or businesses? Why?

8.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Technology

- Contrast a functionalist viewpoint of digital surveillance with a conflict perspective viewpoint.

- In what ways has the internet affected how you view reality? Explain using a symbolic interactionist perspective.

- Describe how a cyberfeminist might address the fact that powerful female politicians are often demonized in traditional media.

- The issue of new media ownership is an issue of growing media concern. Select a theoretical perspective and describe how it would explain this.

- Would you characterize yourself as a technophile or a neo-Luddite? Explain, using examples.