Concepts in Sexualized Violence

This section provides definitions of key concepts related to sexualized violence.

Roots of Violence

There are many different theories and perspectives about what the causes of sexualized violence in our society are. Discussions about ideas such as social constructions of gender roles, colonialism, enslavement, and patriarchy can help us to explore and understand the root causes of sexualized violence and collectively find answers and solutions.

Linking Sexualized Violence and Gender Equity

Sexualized violence is linked to gender inequities in society. The lives, bodies, agency, and work of women, girls, transgender and gender-diverse people are devalued while those of men are overvalued. Devaluing leads to dehumanizing and objectifying; overvaluing leads to entitlement and the misuse of power. Together this forms an environment where sexualized violence perpetrated by men against women and people of diverse genders is normalized. One way to combat the pervasiveness of sexualized violence is to ensure the norms, systems, and institutions in our society are equitable for everyone.

The term rape culture was first coined in the 1970s in the United States by second-wave feminists, and the term is often used in sexualized violence prevention training in post-secondary institutions. Rape culture describes how sexualized violence is common in our society and how it is normalized, condoned, excused, or encouraged. Examples of rape culture include the public tolerance of sexualized harassment, the prevalence of sexualized violence in media, the socialization of boys that promotes masculine identities based on notions of power and control, persistent discrimination against women and other equity-seeking communities, and the scrutiny given to the sexual histories of survivors of sexualized violence (Ending Violence Association of BC, 2016a). While there is a recognition that the term rape culture may not be the most useful or inclusive term, it is currently the most commonly used one to describe the suite of beliefs, values, and actions that allow sexualized violence to be so prevalent.

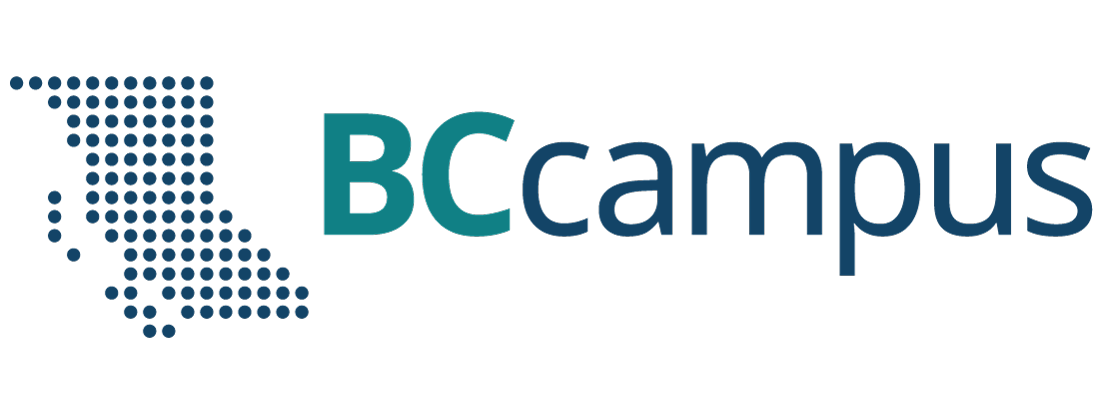

Many aspects of rape culture are often conceptualized as a pyramid or can be connected to other forms of violence in society.

Colonial Violence

Colonialism occurs when a group of people take control of other lands, regions, or territories outside of their own by turning those other lands, regions, or territories into a colony.

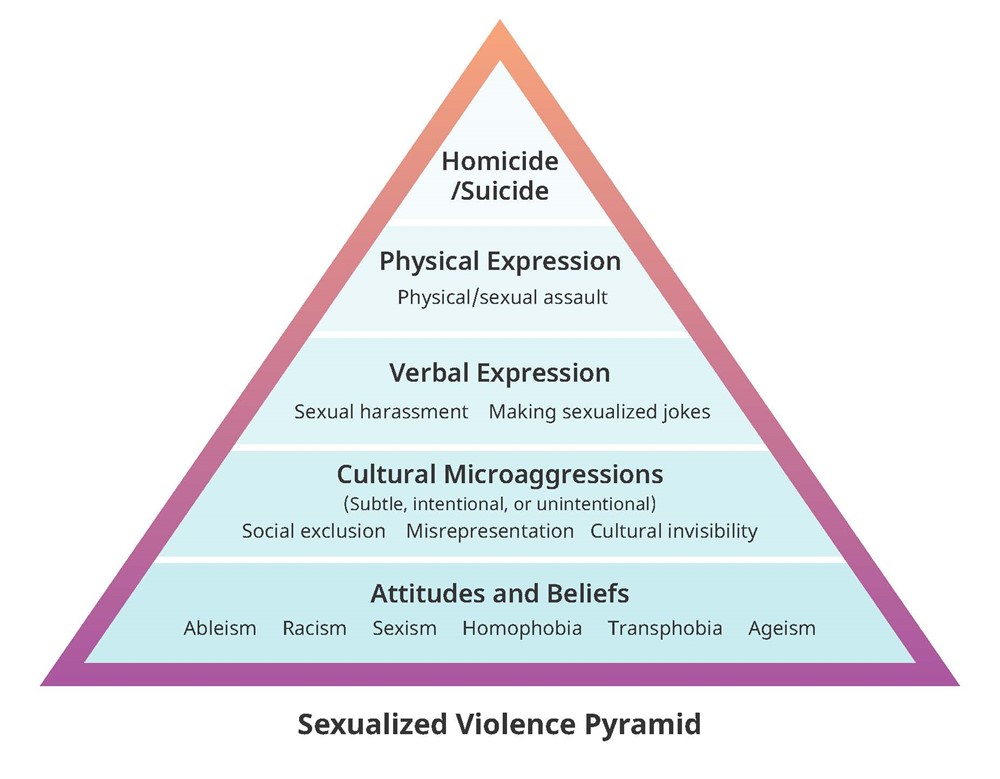

Colonialism remains embedded in Canada’s legal, political, and economic context today. Sexualized violence and colonialism are interconnected through concepts such as self-determination, autonomy, and consent. Also, many social norms in Canada are founded on colonial beliefs, which are rooted in white patriarchal supremacy and which have created systems that support individuals, predominantly white men, to positions of power. These norms provide an illusion that people are entitled to what others have, including lands, cultures, and people’s bodies and that force is an acceptable way to claim these things, regardless of the harm to others (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019; Turpel-Lafond, 2020; Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016). An understanding of colonial violence can help provide context to issues such as why many Indigenous women, girls, gender-diverse, and Two-Spirit people experience high rates of sexualized violence today and the systemic and historical barriers to Indigenous people reporting sexualized violence when it occurs.

Optional Colonial Violence Wheel Activity

If you are offering a longer session and would like to discuss colonial violence in more depth, consider using the Colonial Violence Wheel Activity.

The colonial violence wheel is a visual tool that can be used to help further discussion on the connections between colonial violence and sexualized violence. Each section of the wheel provides examples of strategies, policies, and laws that have been enacted by the Canadian government to colonize and assimilate Indigenous people. Discussion questions can include:

- What do you already know about colonialism in Canada? What aspects of these strategies, policies, and laws do you see in your life?

- How do the strategies, policies, and laws described in the wheel connect to sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination?

- How does colonial violence connect to sexualized violence? For example, what is the connection between self-determination at an individual level (control of one’s own body) and at a community level (First Nations self-governance)?

The Colonial Violence Wheel Activity is available as a handout: Colonial Violence Wheel Activity handout [PDF].

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a concept that promotes an understanding of people as shaped by the interactions of different positionalities or categories – for example, Indigeneity, race, ethnicity, gender identity/expression, class, sexuality, geography, age, ability, migration status, and religion.

In the context of sexualized violence, intersectionality can help increase understanding of how certain populations face increased risks of perpetrating sexualized violence and others face increased risks of being targeted by sexualized violence. It also highlights how different groups of people experience systemic barriers when disclosing sexualized violence and accessing support services. It can also help ensure that responses to sexualized violence are attentive to and reflective of the diversity of communities at post-secondary institutions.

Optional Power Flower Activity

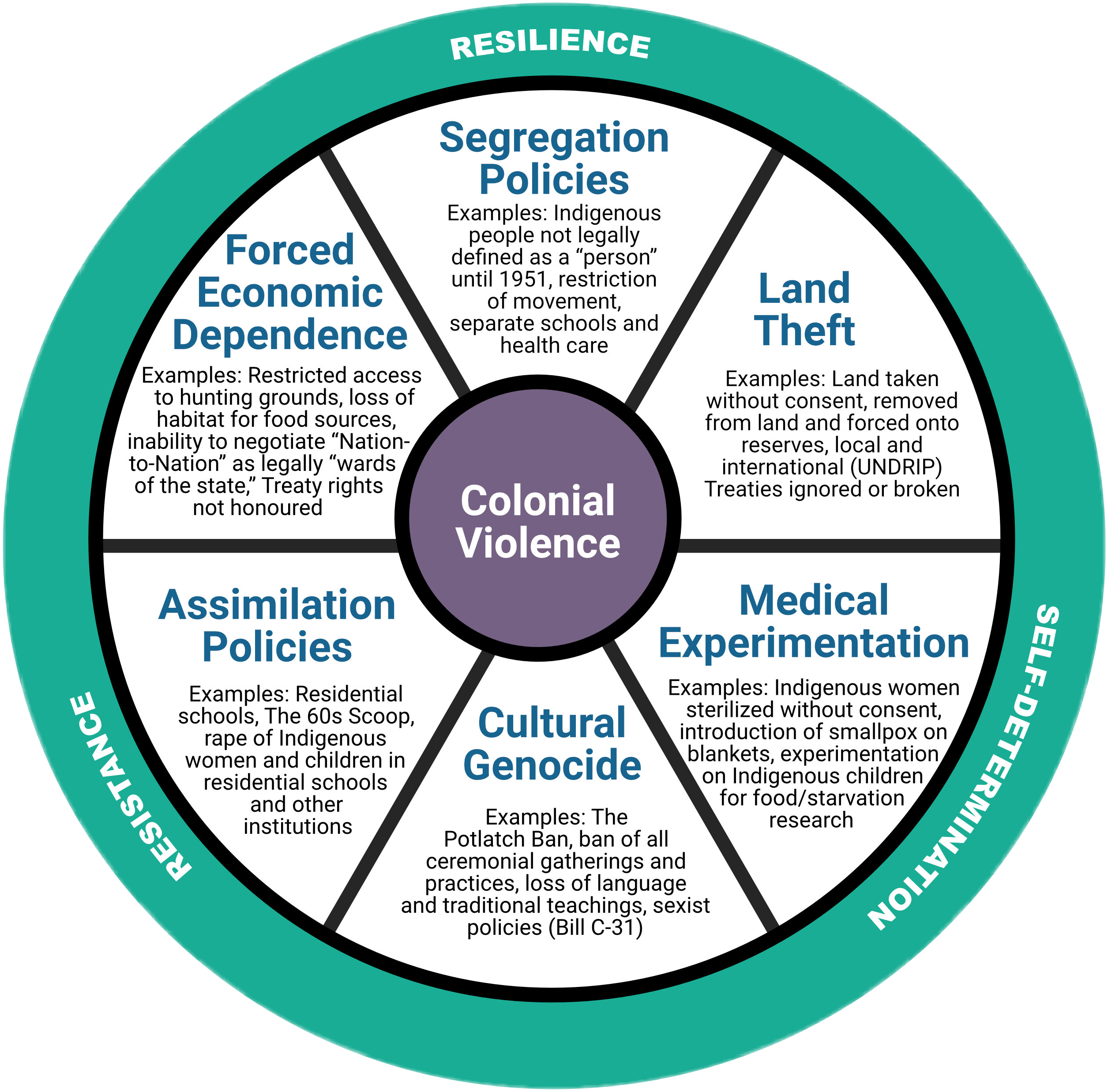

If you are offering a longer session and want to encourage participants to explore intersectionality, consider using the Power Flower Activity below.

Instructions:

- Each person fills out their own power flower, identifying different aspects of their own identities in a number of categories. (Colourful markers or paper are always a bonus!). As we all have many identities, you may want to start with:

- Ethnicity

- Sex

- Gender identity

- Sexual orientation

- Class

- Language

- Ability

- Family

- Education

- Feel free to customize this list based on the participants in your group.

- As a group, reflect on the implications of being able to choose certain aspects of your identity and not others and explore why you might think about certain aspects of your identity more than others. How does thinking through these different categories affect your perspective of yourself? Note: Participants should not be required to share the results of their power flower during the discussion.

- What kind of power do you have? In your own life? As a student, staff, or faculty member?

- What are your strengths? What are your skills? What kind of knowledge do you hold? What resources and supports are available to you?

- How might your power flower shape your experiences, knowledge, beliefs, and values about sexualized violence?

The Power Flower Activity is available as a handout: Power Flower Activity handout [PDF].

Sex, Gender, and Gender Identity

Because the power dynamics of sex and gender are culturally created and enforced, addressing sex, gender, and gender identity in discussions about sexualized violence is essential. Gender can be a complex topic to discuss as there are many elements to consider such as identity, expression, and sex. Western understandings of sex, gender, and gender identity have evolved from a binary view (two options: male and female) to a spectrum that suggests there are multiple sexes (male, female, intersex), many gender identities, and a wide range of gender expressions that may or may not conform to societal expectations. Many cultures have respect and recognition for more than two sexes, genders, or gender identities.

Sex: Biological factors used to describe physiological differences such as gene expression, chromosomes, genitals, and hormones.

Gender: The social roles, expectations, and behaviours that are prescribed to us based on our sex assigned at birth. This can be different between cultures and time.

Gender identity: Our internal understanding of our own gender. It may or may not match what is outwardly apparent to others or what is expected of us by society.

As a facilitator, you will want to be familiar with key terms used to discuss gender. These terms are continuing to evolve, and it is important to refer to people using their own terms. Below are some examples of language related to gender:

- Cisgender: Someone who identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth. Cis is a Latin prefix that means aligned with.

- Transgender: Someone whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. Trans is a Latin prefix that means across, beyond, or through. (Note: Use transgender and not transgendered as the term transgendered is outdated and seen as derogatory).

- Non-binary: Someone who identifies as having a gender outside of the male/ female binary.

- Two Spirit: A specific identity held by some Indigenous people living on Turtle Island (North America). Two-Spirit people may embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and gender roles that differ from colonial understandings of sex and gender. They often hold special cultural, spiritual, or ceremonial roles among their people.

- Sex assigned at birth: The sex that an infant is assigned when they are born. It is based on the combination of hormones, chromosomes, and internal and external genitalia. The three most common options are female, male, and intersex.

- Gender identity: Someone’s personal understanding of their gender. It may or may not align with their body and gender expression.

Gender and 2SLGBTQIA+ Inclusive Language

Inclusive language is important and helps avoid making assumptions about others. As a facilitator, you will want to use language that is inclusive of all people regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, relationship structure(s) (e.g., monogamous, polyamorous) and marital or romantic status.

Because participants are likely to be diverse, it’s important to be respectful of the many ways they experience gender, attraction, and relationships. Sexualized violence is not exclusive; it can happen to and be perpetuated by people of diverse genders, sexes, and attractions.

If you are speaking in general terms, take care to choose terms like intimate partner or partners instead of husband, wife, boyfriend, or girlfriend. If you are referring to a specific person’s intimate partner, use the same language they use. If a person refers to their intimate partner as their spouse or wife, you should use the word they use instead of referring to their partner.

Likewise, using inclusive language will improve participants’ sense of safety. For example, “Good afternoon, everyone,” “Hello, folks,” and “See you all after the break” are inclusive of transgender, non-binary, Two-Spirit, and gender-diverse people while “Welcome, ladies and gentlemen” is exclusive. Similarly, avoid everyday gendered language (e.g. man-hours, spokesman, and waitress should be replaced with work hours, spokesperson/speaker, and server) or historically oppressive turns of phrases such as “rule of thumb.” For decades this expression has been linked to domestic violence as a reference to the maximum width of stick a husband was permitted to beat his wife with. Try using language such as “someone of another gender” and “people of all genders” rather than “the opposite sex” or “both genders.”

Be careful to address or refer to people with similar titles in similar ways. If you refer to a cisgender male professor as “Dr. Last Name,” as a default, refer to all professors using Dr. It can be common for people to default to addressing male professors as Dr., while there is often hesitation to do so for women and gender-diverse professors, which mirrors society’s tendency to ascribe power, authority, and esteem to the knowledge held by men while questioning or devaluing the expertise of women and marginalized genders.

Don’t assume pronouns, sexual orientation (attraction), or gender identity based on someone’s name or appearance. Invite all participants, guests, and co-facilitators to indicate their pronouns and their preferred name on their nametag or in their online display names, if they feel safe doing so. Explain that sharing our pronouns is a way for participants to indicate the language that will help them to feel acknowledged and respected. Be prepared to respond if cisgender people respond to pronoun check-ins in a flippant way (e.g., “Call me anything, I don’t care about pronouns,” or “We’re all people!” or “I don’t believe in pronouns.”) You can respond by saying, “Sometimes it can be hard to understand the importance of certain things when they don’t affect us directly. If this doesn’t feel important to you, ask yourself why that may be, and remember that it can still be important to others even if it feels unimportant to you.” If a participant doesn’t want to share their pronouns, they can just say “pass,” or ask that others refer to them by their name.

Examples of gender-inclusive language:

Language Resource

Inclusive language is continuing to evolve. Qmunity, B.C.’s Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Resource Centre has a resource called Queer Terminology from A to Q that is regularly updated.

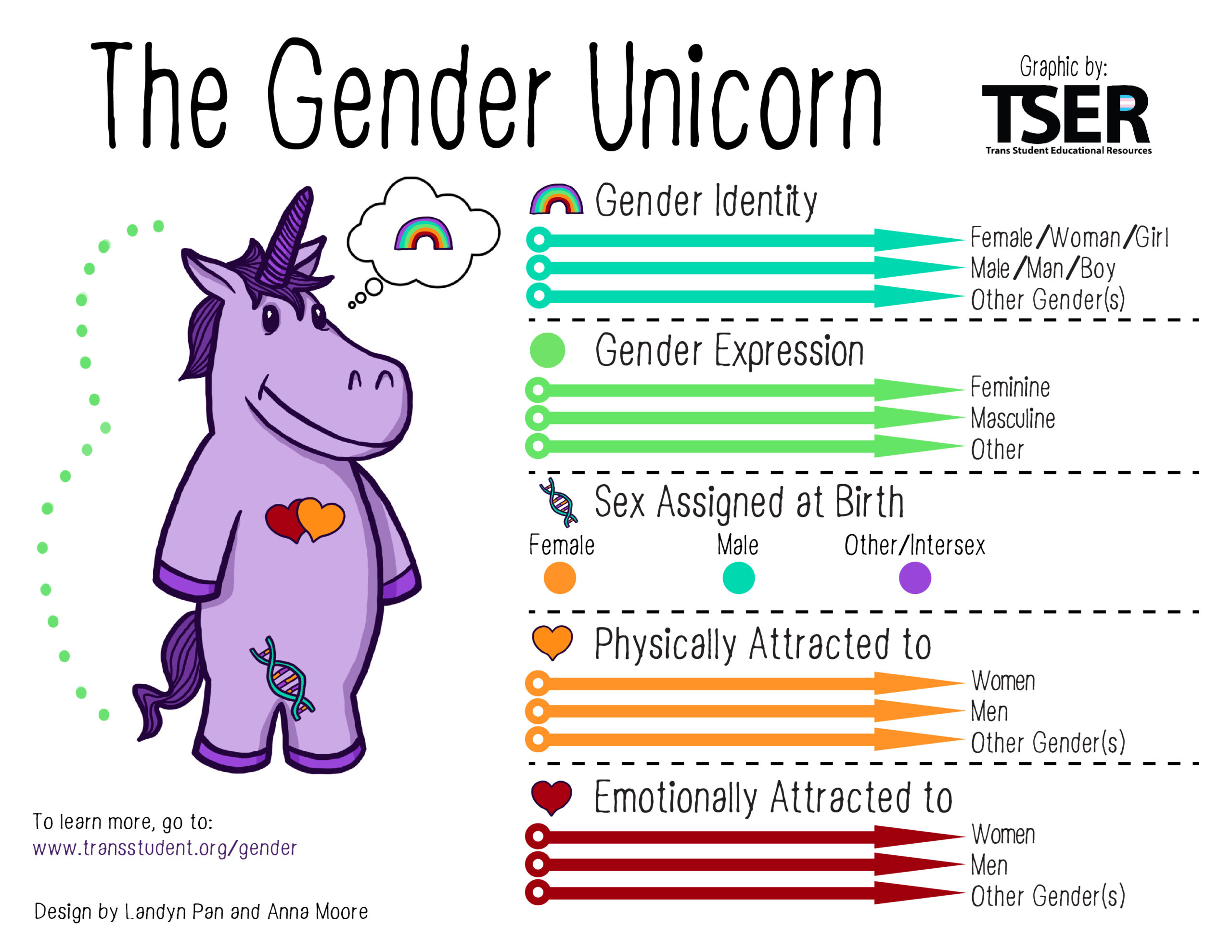

If there is time and participants would like to discuss gender, consider using the Gender Unicorn shown below.

Optional Gender Unicorn Activity

The Gender Unicorn is a visual activity by Trans Student Educational Resources that allows learners to map out their own experiences of sex and gender. It is available in an interactive form, as a colouring book, and in different languages.

Healthy and Toxic Masculinity

Healthy masculinity and toxic masculinity are popular terms often used to explore beliefs, values, and stereotypes related to male identity and masculine norms in society. Masculine identity and norms are strongly linked with violence, with men and boys disproportionately likely both to perpetrate violent crimes and to die by homicide and suicide (Heilman & Barker, 2018).

Sexualized violence prevention and response training at post-secondary institutions will often explore ideas related to masculinity as a way of helping to shift societal ideas about masculinity and to centre new values related to inclusivity and diversity. These conversations can help highlight how sexualized violence harms women, girls, and people of all genders, including men and boys. Conversations about masculinity can also be an entry point for cisgender men to take a role in addressing sexualized violence in their community.

Image Descriptions

Sexualized Violence Pyramid image description

A pyramid representing different aspects of sexualized violence. As you go to higher levels of the pyramid, the degree of violence increases. These are the levels of the pyramid from the bottom to the top:

- Attitudes and beliefs: ableism, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ageism

- Cultural microaggressions (subtle, intentional, or unintentional): social exclusion, misrepresentation, cultural invisibility

- Verbal expression: sexual harassment, making sexual jokes

- Physical expression: physical/sexual assault

- Homicide/suicide

Colonial Violence Wheel image description

A wheel with the words colonial violence in the centre. Within each spoke of the wheel are examples of colonial violence. Surrounding the outer edge of the wheel are the words, Resilience, Resistance, and Self-Determination. Here are the examples of colonial violence:

- Segregation policies. Examples: Indigenous people not legally defined as a “person” until 1951, restriction of movement, separate schools and health care

- Land theft. Examples: Land taken without consent, removed from land and forced onto reserves, local and international treaties (UNDRIP) ignored or broken

- Medical experimentation. Examples: Indigenous women sterilized without consent, introduction of smallpox on blankets, experimentation on Indigenous children for food/starvation research

- Cultural genocide. Examples: The Potlatch Ban, ban of all ceremonial gatherings and practices, loss of language and traditional teachings, sexist policies (Bill C-31)

- Assimilation policies. Examples: Residential schools, the 60s Scoop, rape of Indigenous women and children in residential schools and other institutions

- Forced economic dependence. Examples: restricted access to hunting grounds, loss of habitat for food sources, inability to negotiate “Nation-to-Nation” as legally “wards of the state,” treaty rights not honoured.

Power Flower image description

A flower with two layers of petals. The word name is at the centre.

- The inner layer has six petals that show the words race, ability, education, sexual orientation, gender identity, spirituality/religion.

- The outer layer has six petals that show the words family, class, health, language, housing, age.

Gender Unicorn image description

A purple cartoon unicorn stands beside different ways to describe gender, sex, and attraction. They are as follows:

- Gender identity (a spectrum):

- Female/woman/girl

- Male/man/boy

- Other gender(s)

- Gender expression (a spectrum)

- Feminine

- Masculine

- Other

- Sex assigned at birth

- Female

- Male

- Intersex

- Physically attracted to (a spectrum)

- Women

- Men

- Other gender(s)

- Emotionally attracted to (a spectrum)

- Women

- Men

- Other gender(s)