Main Body

1 Preface

Political theorists – classic writers such as Hobbes and Rousseau but contemporary ones too – have often assumed a neat fit between this government and that territory and its population, as if the fit between the two were somehow natural or timeless. Reality is always messier than that, of course. Countries, or nation-states, are in part constructed entities or communities – political units that are consciously demarcated and separated from others. As Guibernau comments, ‘In seeking to engender a sense of belonging among its citizens the nation-state demands their loyalty and fosters their national identity’ (Guibernau, 2005, Section 3, emphasis added).

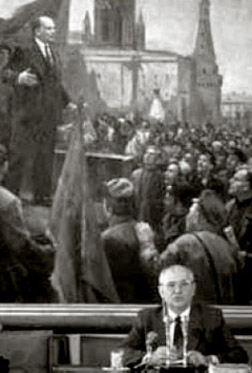

Political theorists have only paid systematic attention to the constructed, engendered aspect of nationhood, and to the ideology of nationalism, in recent years. That is not surprising. For one thing, nations and nationalist movements are all unique in some way. Political theorists find nationalism difficult to generalise about, as opposed to a concept such as ‘legitimacy’ or ‘freedom’. Further, most professional political theorists work in the rich northern countries, where national borders had been stable until the implosion of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. The creation of new states in the ex-Soviet Union, civil wars over nationalist claims in ex-Yugoslavia, and events such as the splitting of Czechoslovakia between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, raised pressing questions of principle and revived interest in political units, borders and nationalism in countries from Italy to the UK to Spain. This renewed interest was also prompted by the revival of sub-nationalist movements. In the UK, for example, such movements played their role in the pressures that led to the establishment of the National Assembly for Wales and the Scottish Parliament. A number of political theorists responded to the challenging questions raised by these developments. In this unit we shall take a critical look at some of the answers put forward, in terms of:

- belonging, loyalty, community and statehood

- the relationship between individual self-determination and collective self-determination

- the range of possible meanings of the idea of the ‘nation’

- nationalism as a political ideology

- the debate on the ‘right’ to national self-determination: when is secession justified?