Why We Need to Talk About Suicide

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Introduction.

Video: Live Through This

Live Through This is a series of portraits and true stories of suicide attempt survivors. Its mission is to change public attitudes about suicide. To start this section, you could show a short four-minute video from the Live Through This website. Alternatively, you could share the link to the video with participants before the session to help them prepare.

Myths and Commonly Misunderstood Ideas

Because we don’t talk about suicide a lot, people often have a lot of questions and there are a lot of misunderstood ideas and myths about suicide. Let’s take some time to talk about some of these myths.

Activity: Talking About Myths and Misunderstood Ideas

In small groups, have participants discuss one of the myths below. You could have each group discuss a different myth and then bring their thoughts back to the larger group for a larger group discussion.

![]() Adaptation

Adaptation

- As a large group, ask participants to share their thoughts about the myths and give everyone an opportunity to ask questions. If the session is online, you could have participants share thoughts and ideas in chat.

You could also ask participants to consider the following questions:

- What myths or stereotypes exist in society about suicide?

- What cultural stereotypes are there about suicide?

- What questions do you have about suicide?

1. Myth: People who talk about suicide are only trying to get attention. They won’t really do it.

Few people die by suicide without first letting someone else know how they feel. Research indicates that up to 80% of people considering suicide signal their intentions to others, in the hope that the signal will be recognized as a cry for help. Signals often include making a joke about suicide, or making a reference to being dead. Over 70% who do express intent to carry out a suicide either make an attempt or die by suicide.

That’s why it is best to take any mention of suicide seriously. If we do take someone seriously and ask them if they mean what they are saying, the worst that can happen is we will learn that they really were not serious. Not asking about suicide could result in a far worse outcome.

2. Myth: Talking to a person about suicide will encourage suicide.

There is no evidence indicating that talking to people about suicide increases their risk of suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviours. Research does indicate that talking openly and responsibly about suicide lets a person know that they are not alone, that there are people who want to listen and help. Most people are relieved to finally be able to talk honestly about their feelings, and this alone can reduce the risk of an attempt.

3. Myth: If someone is seriously contemplating suicide, they don’t want to make a decision to live.

We know that those at risk for suicide do not necessarily want to die but do want help in reducing the pain they are experiencing so that they can go on to lead productive, fulfilling lives. There is a lot of ambivalence surrounding the decision to take one’s own life, and by recognizing this, and discussing it, we can help a person who is suicidal start to recognize alternative options for managing their suffering. People who are suicidal are often experiencing intolerable emotional pain, which they believe to be unrelenting and permanent. They often feel hopeless and trapped. By helping them recognize and explore alternatives to dying, you are planting the seeds of hope that things can improve.

4. Myth: Most suicides happen suddenly without warning.

Most suicides are not sudden; there are usually warning signs that come before. It’s important to learn and understand the warning signs associated with suicide. This session looks at warning signs, which include actions, direct or indirect statements, physical signs, or certain behaviours. When we know how to recognize signs of suicide, we are then better able to take the next step and help someone in distress.

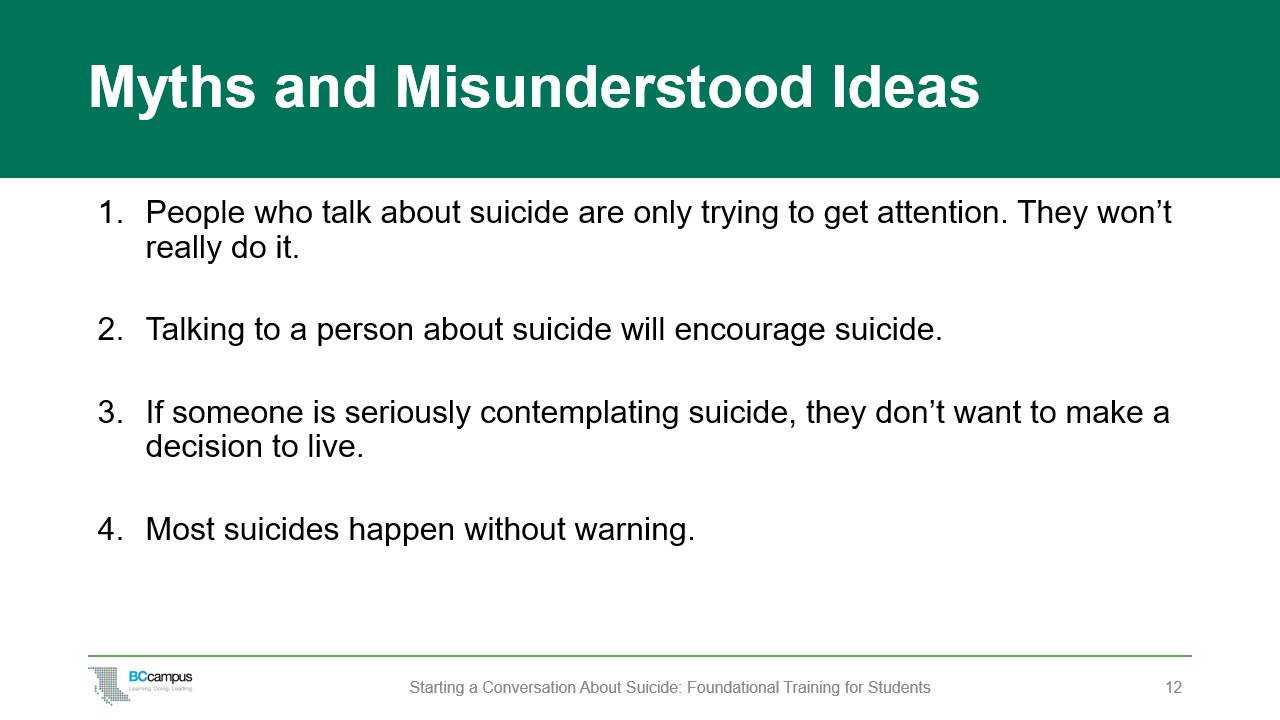

Looking at Statistics

Every expression of suicide needs to be taken seriously because no one can predict who will die by suicide, even though many people have had thoughts of suicide at some point in their lives. Anyone can be at risk for suicide. Let’s have a look at some statistics for more insight.

In the post-secondary context, Canadian data from the 2019 National College Health Assessment[1] tells us that:

- 10.1% of students had seriously considered suicide within the previous 12 months.

- 1.9% had attempted suicide within the previous 12 months.

- 6.0% intentionally cut, burned, bruised, or otherwise injured themselves within the previous 12 months.

(For this survey, 58 Canadian post-secondary institutions self-selected to participate and over 55,000 surveys were completed.)

Statistics don’t take into account the impact that suicide has on others. For each death by suicide, it has been estimated that the lives of 7 to 10 other people will be affected.

The more we have these types of conversations, the more of the iceberg is brought to the surface.

![]() Adaptations

Adaptations

Statistics can quickly show how prevalent suicide or thoughts of suicide are among post-secondary students. The slides include information about suicide in Canada. However, there may be statistics on student mental health and suicide at your institution or in your community that you can use. Or you may want to share information and statistics about groups at higher risk of suicide. Some examples to consider:

- People with experience of abuse, trauma, conflict, or disaster, including bullying, cyberbullying, and peer victimization are at higher risk of suicide.

- Those who have been bereaved or affected by suicide in others may have a higher risk.

Or you may want to use both quantitative data and qualitative data (e.g., brief statements from students).

Risk Factors and Protective Factors

Suicide is a complex topic, and many factors contribute to suicide, rather than a single cause. When a person feels helpless or alone, overwhelmed by pain, fear, and suffering, their hope wanes and they may consider ending their life.

Many people experience passing thoughts of ending their lives without ever having any intention of acting on those thoughts. Suicidal thinking becomes more concerning when it is persistent and driven by increased emotional distress. When a person’s thoughts become directed toward how and when they might kill themselves, the overall level of risk is higher.

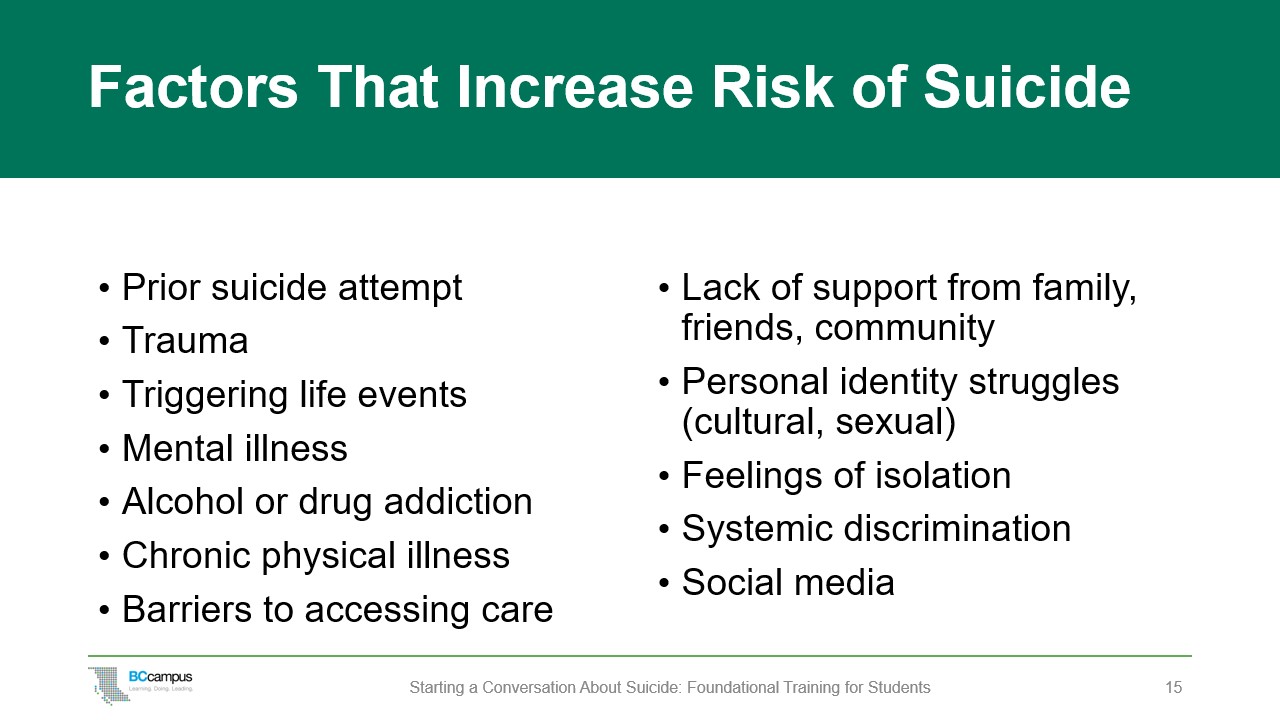

Factors that increase risk of suicide:

- Prior suicide attempt – If someone has attempted suicide in the past, there is an increased risk that they may try it again

- Trauma (violence, abuse, or events that affect generations of one’s family)

- Triggering life events (losing a loved one, physical illness, discrimination, harassment)

- Mental illness, such as depression

- Alcohol or drug addiction

- Chronic physical illness

- Barriers to accessing care

- Lack of support from family, friends, community

- Personal identity struggles (cultural, sexual)

- Feelings of isolation

- Systemic discrimination

- Social media

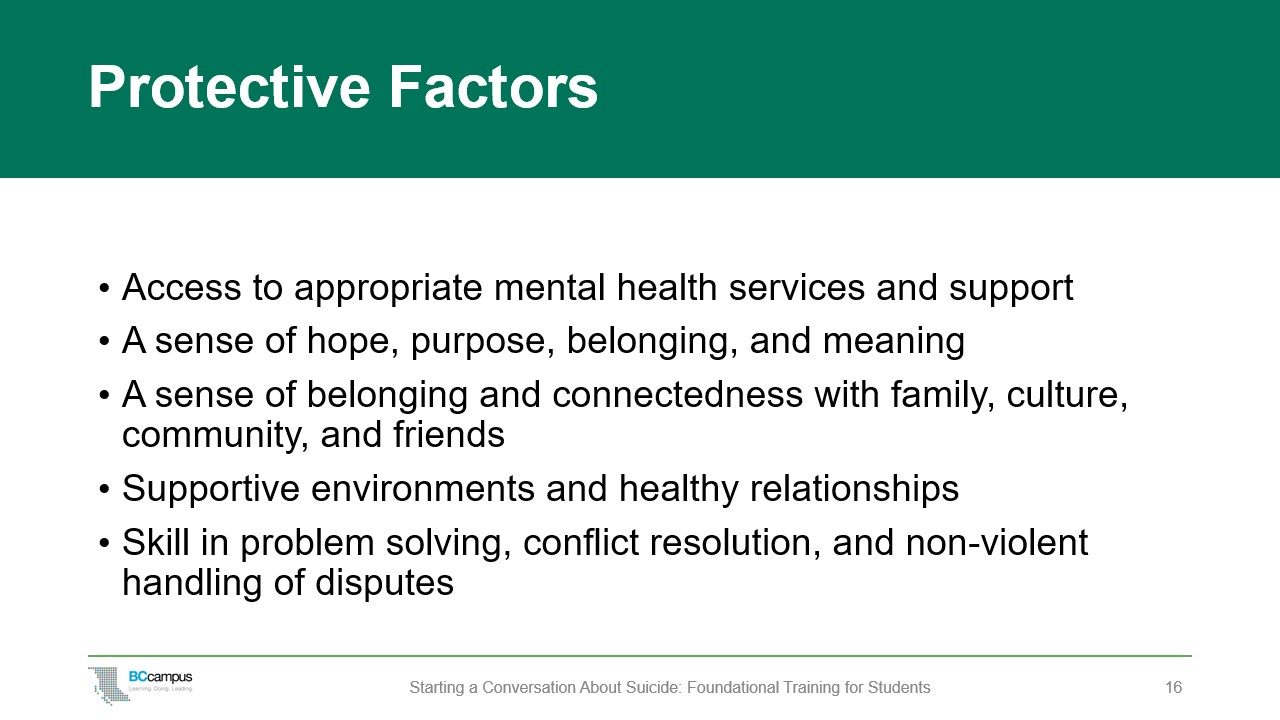

Protective factors include:

- Access to appropriate mental health services and support

- A sense of hope, purpose, belonging, and meaning

- A sense of belonging and connectedness with family, culture, community, and friends

- Supportive environments and healthy relationships

- Skill in problem solving, conflict resolution, and non-violent handling of disputes

Facilitator Note: The Tree of Life

This guide has an image of a cedar branch on the cover. Trees sustain life on earth and are a powerful symbol of growth, interconnection, resilience, and strength. The western red cedar is a particularly important tree for many Indigenous Peoples on the west coast of British Columbia. Below is one perspective on the importance of the red cedar tree to Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people.

In the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Nation, the red cedar is known as our tree of life. This tree expresses our responsibility as stewards of the land. The roots of a red cedar tree go deep, and when they are connected to other trees, they can share natural resources to support the health of the forest communally. Ever since the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people came into existence thousands of years ago, from our birth to the ceremony mourning our passing as individuals, the tree of life has played – and continues to play – a crucial role in every aspect of our lives.

Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people have sacred teachings on sustainably harvesting the bark of red cedars for our regalia, our woven cedar hats, or our headbands; this regalia plays a vital role in our Potlatch ceremonies. The tree of life is often in our artwork, our regalia; it represents the spirit of hope our communities have for our families, our communities, and the other nations interconnected with ours.

The connection between our traditional teachings and protocols around red cedars is very similar to how we support people in mental health distress. A sense of connection, community, dignity, and respect are essential.

So much of a tree’s determinants of health lie within the soil, a place we cannot see. When supporting a student who is very distressed and possibly considering suicide, it is important to remember all of the protective factors they may have below the surface:

- Counselling support

- Family and friends

- Community supports

- Spiritual or religious beliefs or practices

Our role in supporting others with suicidal ideation is to determine the most appropriate resources to help them, in the same way as the roots of the tree of life share their resources with the forest around them.

—Jewell Gillies, Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Nation (Ukwana’lis, Kingcome Inlet, B.C.)

Marginalized Groups

When we talk about mental health and suicide risks, we also need to be aware of factors like race, sexual orientation, social class, age, disability, and gender and the unique life experiences and stressors that accompany them. Some students face inequality, discrimination, and violence because of their race and/or gender orientation. These unique and specific stressors impact mental and physical health, and these students often experience greater mental health burdens while at the same time facing more barriers to accessing care.

We all need to take care to understand and acknowledge oppression faced by some groups. By providing a culturally safe environment, we can all play a role in ensuring that each student feels that their personal, social, and cultural identity is respected and valued. Here are some things to keep in mind.

Indigenous Students

Suicide among Indigenous people is significantly higher than in the general population. Estimates suggest that, in some years, the suicide rate for Indigenous people in specific communities is three times higher than that for non-Indigenous people.[2]

Suicide rates are highest for youth and young adults (15 to 24 years) among First Nations men and Inuit men and women. However, there is great variability in suicide rates at the community level; some Indigenous communities may have a very high suicide rate; other communities may have a very low rate.

For Indigenous communities, high rates of suicide are connected with a variety of factors, including historical and ongoing trauma from colonialism, systemic racism, discrimination, and the loss of culture and language. The impacts of residential schools and other colonial policies have created ongoing adversity for Indigenous people, and these effects have been passed on from one generation to the next, causing intergenerational trauma.

Many Indigenous people lack trust in educational and health care institutions because of the negative or traumatic experiences they or their family and friends have experienced in the past. The 2020 report In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care reported on the widespread systemic racism against Indigenous people in the B.C. health care system. The study reported that 84% of Indigenous people described personal experiences of racism and discrimination that discouraged them from seeking necessary care.[3]

It is important to note, however, that while the suicide rate is higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people, not all Indigenous communities have regular occurrences of suicide. In communities where there is a strong sense of culture, community ownership, and other protective factors, it is believed that there are much lower rates of suicide and sometimes none at all.[4]

International Students

Both undergraduate and graduate international students are often away from home for the first time and under a lot of pressure. The stakes may be very high for them: their tuition is expensive, they’ve travelled a long way to attend a post-secondary institution in B.C., and they feel a lot of pressure to do well academically. They may be struggling to adjust to a new culture or learn English, and they may be missing home, family, and friends. The understanding of mental health and wellness differs among cultures, and international students may have a different understanding of how mental health impacts academic performance, and they may not be aware of the support systems available to them when they arrive. There are also systemic barriers that international students may face, including visa requirements, that don’t allow for flexibility in course workloads when they are struggling.

In some cultures, such as South Asian cultures, mental illness is stigmatized, and students may be uncomfortable talking about it. Keep in mind that the mental health words we use in English may not exist in other languages, as mental health is rarely discussed in some cultures.

LGBTQ2S+ Students

People who are LGBTQ2S+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit) are at a much higher risk than the general population for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide. Homophobia and negative stereotypes about being LGBTQ2S+ can make it challenging for a student to let people know about this important part of their identity. When people do openly express this part of themselves, they worry about potential rejection by peers, colleagues, and friends, and this can exacerbate feelings of loneliness. Health needs may be unique and complex for some LGBTQ2S+ people, and health care settings can feel unsafe or uncomfortable for many.

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are more at risk for suicide than their straight peers. They are five times more likely to consider suicide and seven times more likely to attempt suicide.[5]

Transgender people are at an even greater risk for suicide as they are twice as likely to think about and attempt suicide than LGB people.[6] Studies have shown that 22% to 43% of transgender people have attempted suicide.[7] Transgender people face unique stressors, including stress from being part of a minority group, as well as stress related to not identifying with one’s biological sex. Transgender people also experience higher rates of discrimination and harassment than their cisgender counterparts and, as a result, experience poorer mental health outcomes.

While there is a growing awareness of the needs and challenges faced by LGBTQ2S+ community members, much still needs to be done to create truly inclusive and safe spaces within health and educational environments.

Students with a Disability

Many students live with some form of physical, cognitive, sensory, mental health, or other disability. Students of all abilities and backgrounds deserve post-secondary settings that are inclusive and respectful. Unfortunately, many institutions are not designed to fully support people who need extra accommodation, and students with a disability frequently encounter accessibility challenges and extra barriers to achieving academic success. In addition to navigating the complex environment of a post-secondary institution that is not set up for them, students with a disability also often have to combat negative stereotypes, bias, and discrimination. These many extra challenges can take a toll on mental health.

Racialized Students

Black, Indigenous, and other racialized students have likely faced racism and discrimination throughout their lives. Racism can encompass a range of words and actions, from the overt racism of violence or slurs to microaggressions (everyday, subtle interactions that demean or put down a person based on their race). Sometimes microaggressions are not intentional, but they can still be very harmful, and they are a form of racism that many students experience. These repeated negative interactions can be overwhelming at times, especially in post-secondary spaces where a student could reasonably assume they would be free from any form of bullying, harassment, or discrimination.

What We Need to Keep in Mind

Anyone can be at risk of suicide. However, racism and other forms of discrimination can have a significant impact on a student’s mental health and can lead to increased risk of depression or suicide, and increased levels of anxiety, stress-related illnesses, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

It is helpful to know the campus and community resources for students from marginalized groups. Connecting an Indigenous student with an Elder or with someone from Indigenous services, or introducing an LGBTQ2S+ student to a pride centre on campus, can help reduce feelings of isolation and help students feel heard and supported. We’ll talk more about supports and referrals a bit later in the session.

What we want to remember is that by providing a culturally safe environment, we can all play a role in ensuring that each student feels that their personal, social, and cultural identity is respected and valued.

![]() Adaptations

Adaptations

There may not be time in this session to address the realities, challenges, and supports for all marginalized students, but you should consider the student population at your institution and adapt this section accordingly. Identify and provide a diverse range of resources to ensure support for all students.

Activity: Discussion

Either in small groups or as a large group, ask participants to discuss the following:

- How do you react to hearing this information about suicide?

- Have you found yourself in a situation where you were trying to support someone with these concerns or other serious concerns?

- What’s it like for you when you’re trying to help someone else out?

- What do you need in order to feel more helpful to others?

Text Attributions

- “Risk Factors and Protective Factors” and “Marginalized Groups” by Barbara Johnston. “The Tree of Life” by Jewell Gilles (CC BY 4.0 License).

Media Attributions

- What Is Live Through This by Dese’Rae L. Stage, Live Through This Productions, is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

- Cedar tree by anonymous is licensed under CC0 Public Domain Dedication.

- Iceberg in the Arctic with underside exposed by AWeith is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 License.

- Silhouette by anonymous is licensed under CC0 Public Domain.

- American College Health Association (2019), American College Health Association – National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group, Data report, Spring 2019, American College Health Association, https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_CANADIAN_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf ↵

- Kumar, M. B., & Tjepkema, M. (2019), Suicide Among First Nations People, Métis and Inuit (2011–2016): Findings from the 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC), Statistics Canada, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/99-011-x/99-011-x2019001-eng.htm ↵

- Turpel-Lafond, M. E. (2020), In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care, https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf ↵

- Kirmayer, L. J., Brass, G. M., Holton, T., Paul, K., Simpson, C., & Tait, C. (2007), Suicide among Aboriginal people in Canada, Aboriginal Healing Foundation. ↵

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center (2008), Suicide risk and prevention in gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youth, http://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/migrate/library/SPRC_LGBT_Youth.pdf ↵

- Haas, A., et al. (2011), Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations: Review and recommendations, Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1),10–51, DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038; McNeill, J., et al. (2017). Suicide in trans populations: A systematic review of prevalence and correlates. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(3) 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000235; Irwin, J., et al. (2014), Correlates of suicide ideation among LGBT Nebraskans, Journal of Homosexuality, 61(8), 1172–1191. ↵

- Bauer, G., et al. (2015), Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven suicide risk sampling study in Ontario, Canada, BMC Public Health, 15, 525, DOI: 10.1186/ s12889-015-1867-2 ↵