Section 2: Considerations for Facilitators

Sexual Violence: Key Concepts and Facilitation Strategies

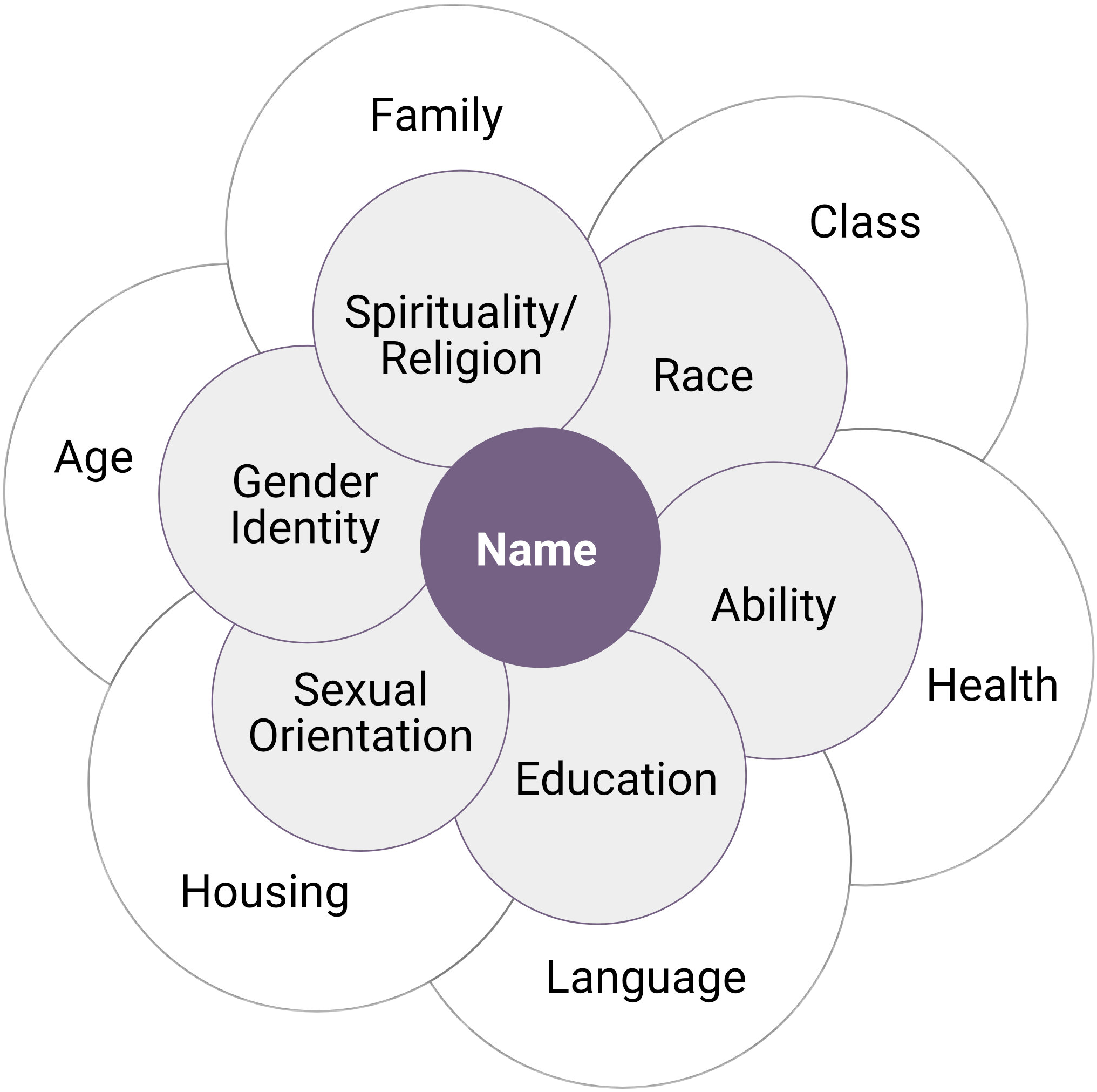

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a concept that promotes an understanding of people as shaped by the interactions of different social locations or categories ― for example, race, ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, ability, migration status, and religion.

In the context of sexual violence, intersectionality can help increase understanding of how certain populations face increased risks of perpetrating sexual violence and others face increased risks of being targeted by sexual violence. It also highlights how different groups of people experience systemic barriers to disclosing and accessing support services. It can also help ensure that responses to sexual violence are attentive to and reflective of the diversity of campus communities.

Examples of facilitation strategies related to the concept of intersectionality

- As you facilitate discussion, you can highlight key ideas related to sexual violence and intersectionality. For example, you could say:

- “Violence does not happen in a vacuum and it isn’t merely a result of individual circumstances or bad luck.”

- “People’s circumstances, such as their income, housing situation, and access to health care, can affect their ability to access resources to heal from their experiences.”

- “When we take a look at ‘big picture’ issues like discrimination, economic conditions, and social policies, we can better understand why certain individuals might be reluctant to report that they have been assaulted.”

- “Even though LGBTQ2SIA+ people experience high rates of violence, when compared to the general population, they are often fearful of accessing the justice system due to a history of negative interactions with police and daily experiences of discrimination and harassment.”

- “Many international students are resilient and determined to thrive and make Canada their home. However, they might face unique barriers when it comes to sexual violence such as language barriers, lack of knowledge about services and supports, or work exploitation.”

- In your training, include statistics, images, and other resources that reflect the perspectives, needs, experiences, and interests of diverse groups. For example, images of a mixed race queer couple with a visible disability gives recognition that race, sexual orientation, and ability can be places of diversity within one relationship. Or, include statistics on sexual violence and resilience within queer and polyamorous couples as well as straight, monogamous couples.

- If you are using statistics about a particular group of people, use precise language to avoid confusion. For example, “Men are likely to be the perpetrators of sexual violence against women” is less accurate than “Cisgender men are likely to be the perpetrators of sexual violence against all other genders, especially against cisgender women.” Your use of precise language will vary based on the information you will be sharing,

- Depending on your audience, you can include a resource or section about intersectionality in your training. This could be a more academic resource such as an interview with legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (while many people have used intersectional perspectives in their work, her use of the term in 1989 has greatly influenced current understandings) or an experiential resource such as an interview or spoken word video by a survivor of sexual violence that highlights multiple social locations.

- If you have more time, you can include a reflective activity such as the Power Flower (below).

Activity: Power Flower

The Power Flower is a visual tool that we can use to explore how our multiple identities combine to create the person we are.

Instructions:

- Each person fills out their own power flower, identifying different aspects of their own identities in a number of categories. (Colourful markers or paper are always a bonus!). As we all have many identities, you may want to start with:

- Ethnicity

- Sex

- Gender identity

- Sexual Orientation

- Class

- Language

- Ability

- Family

- Education

Feel free to customize this list to your audience and the focus of your training.

- As a group, reflect on the implications of being able to choose certain aspects of your identity and not others and explore why you might think about certain aspects of your identity more than others. How does thinking through these different categories affect your perspective of yourself?

- What kind of power do you have? In your own life? As a student, staff or faculty member?

- What are your strengths? What are your skills? What kind of knowledge do you hold? What resources and supports are available to you?

- How might your power flower shape your experiences, knowledge, beliefs, and values about sexual violence?

This Power Flower activity is adapted from: Arnold, R., Burke, B., James, C., Martin, D., and Thomas, B. (1991). Educating for Change. Toronto: Between the Lines. Available from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED336628.pdf

This Power Flower activity is adapted from: Arnold, R., Burke, B., James, C., Martin, D., and Thomas, B. (1991). Educating for Change. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Download the Power Flower Activity here: Handout Power Flower Activity [Word file].

Sex, Gender, and Gender Identity

Because of the power inherent in sex and gender dynamics and the role they play in our lives, addressing sex, gender, and gender identity in discussions about sexual violence is essential. Gender can be a complex topic to discuss as there are many elements to consider such as identity, expression, orientation, and sex. Western understandings of sex, gender and gender identity have evolved from a binary view (two options: male and female) to a spectrum which suggests there are multiple sexes (male, female, intersex), many gender identities, and a wide range of gender expressions that may or may not conform to societal expectations. Many cultures have respect and recognition for more than two sexes, genders or gender identities. This is true not only abroad, but among many nations Indigenous to Turtle Island (North America).

Sex: Biological factors used to describe physiological differences such as gene expression, chromosomes, genitals, and hormones.

Gender: The social roles, expectations, and behaviours that are prescribed to us based on our sex assigned at birth. This can be different between cultures and time.

Gender Identity: Our internal understanding of our own gender. It may or may not match what is outwardly apparent to others or what is expected of us by society.

As a facilitator, you will want to be familiar with key terms used to discuss gender. These terms are continuing to evolve and it is important to refer to people using their own terms.

| Cisgender | Refers to someone who identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth. Cis is a Latin prefix which means aligned with. |

|---|---|

| Transgender | Refers to someone whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. Trans is a Latin prefix which means across, beyond or through. (Note: use transgender and not transgendered as the term transgendered is outdated and seen as derogatory). |

| Non-binary | Refers to someone who identifies as having a gender outside of the male/female binary. |

| Two-Spirit | Refers to a specific identity held by some people Indigenous to Turtle Island (North America). Two-Spirit people may embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and gender roles than those prescribed by colonial understandings of sex and gender. They often hold special cultural, spiritual, or ceremonial roles among their people. |

| Sex assigned at birth | Refers to the sex that an infant is assigned when they are born. It is based on the combination of hormones, chromosomes, and internal and external genitalia. The three most common options are female, male, and intersex. |

| Gender Identity | Refers to someone’s personal understanding of their gender. It may or may not align with their body and gender expression. |

Regularly Updated Language Resource

Inclusive language is continuing to evolve. Qmunity, BC’s Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Resource Centre has a resource called Queer Terminology from A to Q that is regularly updated.

Examples of facilitation strategies related to the concepts of sex, gender, and gender identity

- When talking about diverse experiences of sexual violence, take care to be both inclusive of LGBTQ2SIA+ people while being precise when talking specifically about sexual violence committed by cisgender men against cisgender women.

Key discussion points can include:- The overwhelming majority of acts of sexual violence are committed by cisgender men against cisgender women and girls and people of other genders. Transgender, Two-Spirit, and non-binary people as well as lesbian, gay, and other queer people are disproportionately targeted by perpetrators of sexual violence.

- It’s important to remember that straight, cisgender men and boys can also be targeted and that people of all genders and sexual orientations may be perpetrators of sexual violence.

- We need to be mindful of the experiences of all victims of sexual violence while not minimizing the deep-rooted experiences of violence that cisgender women, girls, and gender diverse people are subjected to by cisgender men.

- Gendered sexual violence exists and thrives in the context of colonialism which privileges straight, white, able-bodied men while unjustly mistreating LGBTQ2SIA+, BIPOC, and disabled people. Because of these intersecting oppressions, people of colour, women, children, and queer people are especially at risk of being targeted by sexual violence.

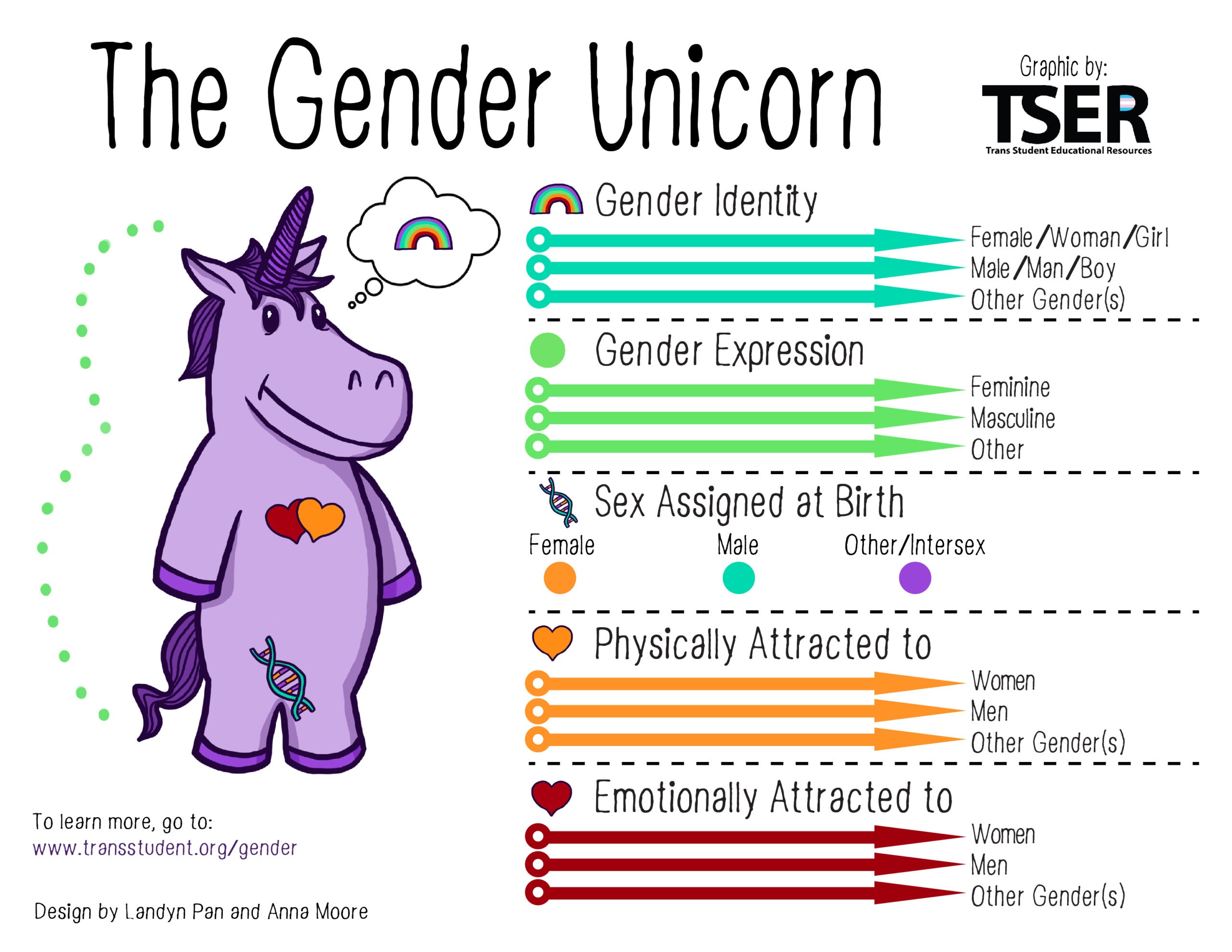

- Help people learn more about gender by including an activity in your training that explores concepts such as gender identity, attraction (sexual orientation), and gender expression (presentation).

Activity: Gender Unicorn

The Gender Unicorn is a visual activity by Trans Student Educational Resources that allows learners to map out of their own experiences of sex and gender. It is available in an interactive form, as a colouring book, and in different languages. (It uses a Creative Commons license and can be shared as long as credit is given.)

“The Gender Unicorn” © Trans Student Educational Resources (2015). [Image description] - When facilitating, pay attention to the pronouns that you use as they are an important part of language related to gender. In addition to the binary English terms “she/her/her” and “he/his/him,” some people use gender-neutral pronouns such as “they/them” (in singular form). Use the pronouns that correspond to a person’s gender identity. As it is not possible to assume pronouns based on appearances, it is a good practice to ask for a person’s pronouns. For some people, being referred to intentionally and repeatedly with inappropriate or incorrect pronouns (or being “misgendered”) can be hurtful, offensive, and violent.

Roots of Violence

There are many different theories and perspectives about what the causes of sexual violence in our society are. Discussions about ideas such as social constructions of gender roles, colonialism, enslavement, and patriarchy can help us to explore and understand the root causes of sexual violence and to collectively find answers and solutions.

Linking Sexual Violence and Gender Equity

Sexual violence is linked to gender inequities in society. The lives, bodies, agency, and work of women, girls, transgender people, and other gender diverse people are devalued while those of men are overvalued. Devaluing leads to dehumanizing and objectifying; overvaluing leads to entitlement and the misuse of power. Together this forms an environment where sexual violence perpetrated by men against women and people of diverse genders is normalized. One way to combat the pervasiveness of sexual violence is to ensure the norms, systems, and institutions in our society are equitable for people of all genders.

The term “rape culture” was first coined in the 1970s in the United States by second-wave feminists and the concept is often used in sexual violence prevention training in post-secondary institutions. Rape culture describes how sexual violence is common in our society and how it is normalized, condoned, excused, or encouraged. Examples of rape culture include the public tolerance of sexual harassment, the prevalence of sexual violence in media, the socialization of boys that promotes masculine identities based on notions of power and control, persistent discrimination against women and other equity-seeking communities, and the scrutiny given to the sexual histories of victims of sexual violence (Baker, 2014; EVA-BC, 2016).

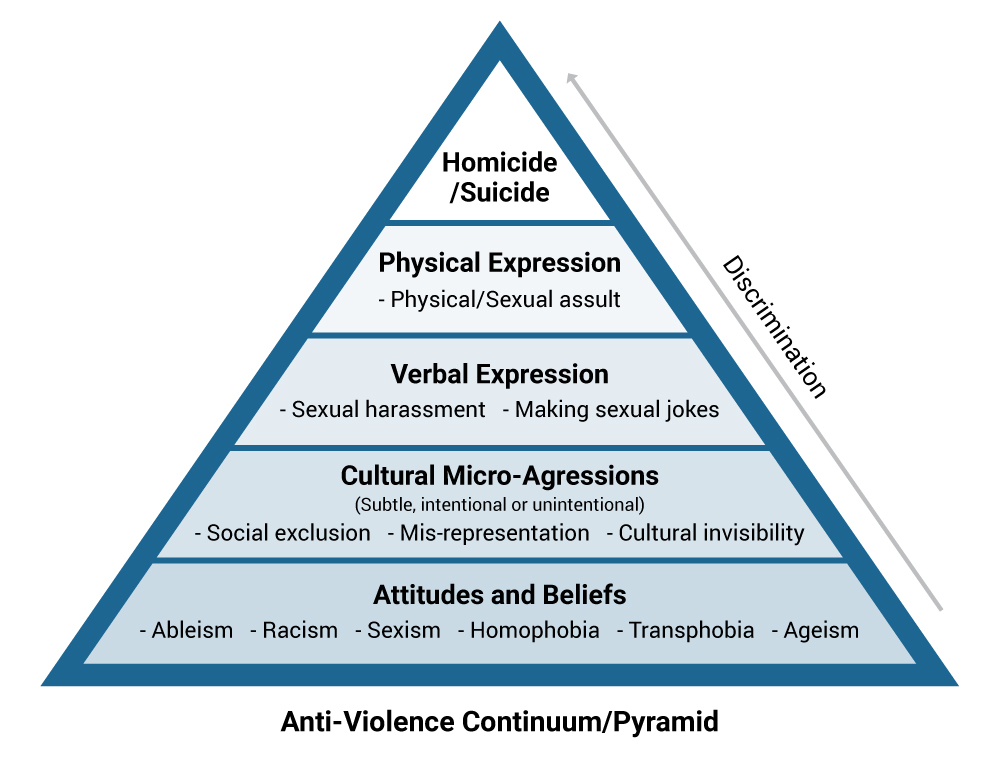

Many aspects of rape culture are often conceptualized as a continuum or pyramid or can be connected to other forms of violence in society.

Examples of facilitation strategies related to the concept of roots of violence

- Ask learners about their perceptions of campus safety: Do they feel safe all the time? Some of the time? What affects their sense of safety? What kind of role do we as campus community members have in preventing sexual violence and/or helping to promote norms of respect, safety, equity, and helping others? (As safety can be a deeply personal subject, you may want to facilitate this discussion in a structured way such as using specific examples or asking questions that require limited self-disclosure).

- You can connect your training to current events and media coverage, e.g., a news story about a high-profile sexual assault case that is in court, the latest opinions about the activities of a famous or infamous celebrity. To what extent are individuals held responsible for their actions and to what extent is society?

- You can include a section in your training on critical media analysis, e.g., reviewing advertisements and exploring what messages they communicate about dating, relationships, and sex. Do these advertisements reflect or challenge current attitudes and stereotypes about sexual violence?

Colonial Violence

Colonialism occurs when a group of people take control of other lands, regions, or territories outside of their own by turning those other lands, regions, or territories into a colony.

Colonialism remains embedded in the legal, political and economic context of Canada today.

Sexual violence and colonialism are interconnected through concepts such as self-determination, autonomy and consent. As well, many social norms in Canada are founded on colonial beliefs which are rooted in white patriarchal supremacy and which have created systems that support individuals, predominantly white men, to positions of power. These norms provide an illusion that people are entitled to what others have, including lands, cultures, and people’s bodies and that force is an acceptable way to claim these things, regardless of the harm to others (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019; Turpel-Lafond, 2020; Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016). An understanding of past and ongoing colonial violence can help provide context to issues such as why many Indigenous people and communities experience high rates of sexual violence today and the potential systemic or historical barriers to Indigenous People reporting sexual violence when it occurs.

Examples of facilitation strategies related to the concept of colonial violence

- During your training, you can discuss how your institution and/or campus unit/department is demonstrating accountability to Indigenous communities and peoples whose land you are on. It is especially important to highlight that reconciliation is a journey and not a destination. This helps to be able to speak frankly about the limitations or meaningfulness of specific initiatives and policies at your institution and to respectfully acknowledge the difficulty in repairing hundreds of years of harm.

- During discussions, you can make connections between colonization (non-consensual theft of land and violence/devaluing of Indigenous People, women, Two-Spirited people and members of the LGBTQ2SIA+ community) and sexual violence (non-consensual sexual touch and/or behavior, devaluing of people’s autonomy). In particular, you can make a connection between land and consent – Canada as a nation is built upon a fundamental lack of consent of Indigenous peoples

- Many people from diverse parts of the world have their own experiences of colonial violence and oppression. It can be helpful to acknowledge this as it helps people to build connections between their own experiences and those of Indigenous People. You will also want to keep in mind that individuals from these groups may be reminded of their own experiences when hearing about the injustices faced by Indigenous People and may benefit from learning about additional resources and supports.

- When discussing the impact of sexual violence as a tool of colonization and genocide against Indigenous communities, you can also highlight the resiliency and capacity of Indigenous peoples and communities to resist and overcome violence.

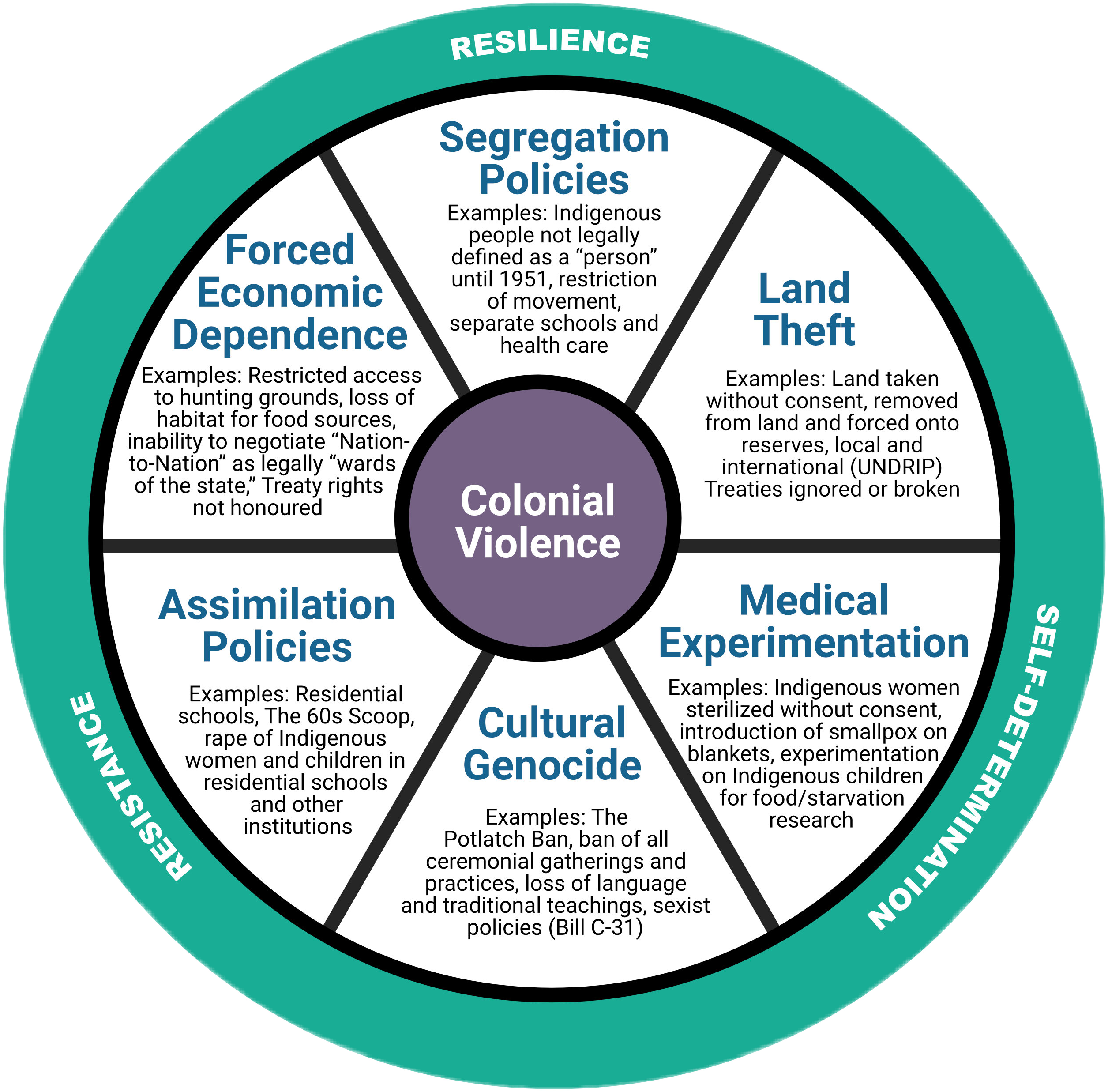

Activity: Colonial Violence Wheel

This Colonial Violence Wheel is a visual tool that can be used to help further discussion on the connections between colonial violence and sexual violence. Each section of the wheel provides examples of strategies, policies, and laws that have been enacted by the Canadian government to colonize and assimilate Indigenous people. Discussion questions can include:

- What do you already know about colonialism in Canada? What aspects of these strategies, policies and laws do you see in your life?

- How do the strategies, policies, and laws described in the Wheel connect to sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination?

- How does colonial violence connect to sexual violence? For example, what is the connection between self-determination at an individual level (control of one’s own body) and at a community level (First Nations self-governance)?

Download the Colonial Violence Wheel Activity here: Handout Colonial Violence Wheel Activity [Word file].

Healthy and Toxic Masculinity

“Healthy masculinity” and “toxic masculinity” are popular terms often used to explore beliefs, values, and stereotypes related to male identity and masculine norms in society. Masculine identity and norms are strongly linked with violence, with men and boys disproportionately likely both to perpetrate violent crimes and to die by homicide and suicide (Heilman and Barker, 2018).

Training on sexual violence on campuses will often explore ideas related to masculinity as a way of helping to shifting societal ideas about masculinity and to centre new values related to inclusivity and diversity. These conversations can help highlight how sexual violence harms people of all genders, including boys, men, and masculine people. It also can be an entry point for cisgender men to take a role in addressing sexual violence in their community.

Examples of facilitation strategies related to healthy and toxic masculinity

- When discussing toxic masculinity is important to be clear that this term does not mean that men are bad or evil. It does not mean that men are naturally violent or that only men are violent.

- The topic of healthy and toxic masculinity can often fit well in discussions of why sexual violence happens in society. Questions to explore can include:

- What ideas do we as a society have about what it means to “be a man”?

- Who or what defines masculinity in our society?

- How does this affect boys, men, and masculine people?

- How might these ideas be related to sexual violence against all genders in our society?

- Can you be masculine without being aggressive or violent?

- How might the experience of masculinity differ for a non-binary person, a trans-masculine person or a masculine woman versus a man who was assigned male at birth?

- Support boys, men, and masculine people in re-defining what healthy masculinity looks like for them. Suggest that there is more than one way to be a man (or any other gender identity). Connect healthy masculinity to topics such as asking consent, respecting boundaries, and being accountable.

Image descriptions

Gender Unicorn image description.

A purple cartoon unicorn stands beside different ways to describe gender, sex, and attraction. They are as follows:

- Gender identity (a spectrum):

- Female/woman/girl

- Male/man/boy

- Other gender(s)

- Gender expression (a spectrum)

- Feminine

- Masculine

- Other

- Sex assigned at birth

- Female

- Male

- Intersex

- Physically attracted to (a spectrum)

- Women

- Men

- Other gender(s)

- Emotionally attracted to (a spectrum)

- Women

- Men

- Other gender(s)

Anti-Violence Continuum/Pyramid image description.

A pyramid representing different aspects of rape culture. As you go to higher levels of the pyramid, the degree of discrimination increases. These are the levels of the pyramid from low to high:

- Attitudes and beliefs, including ableism, racism, sexism, homophabia, transphobia, and ageism.

- Cultural microaggressions, which can be subtle, intentional, or unintentional. These can include social exclusion, misrepresentation, and cultural invisibility.

- Verbal expression, which can include sexual harassment and making sexual jokes.

- Physical expression, which can include physical and/or sexual assault.

- Homicide and or suicide.

Colonial Violence Wheel image description.

A wheel with the words “colonial violence” in the centre. Within each spoke of the wheel are examples of colonial violence. Surrounding the outer edge of the wheel are the words, “resilience,” “resistance,” and “self-determination.” Here are the examples of colonial violence:

- Segregation policies. Examples: Indigenous people not legally defined as a “person” until 1951, restriction of movement, separate schools and health care.

- Land theft. Examples: Land taken without consent, removed from land and forced onto reserves, local and international treaties (UNDRIP) ignored or broken.

- Medical experimentation. Examples: Indigenous women sterilized without consent, introduction of smallpox on blankets, experimentation on Indigenous children for food/starvation research.

- Cultural genocide. Examples: The Potlatch Ban, ban of all ceremonial gatherings and practices, loss of language and traditional teachings, sexist policies (Bill C-31).

- Assimilation policies. Examples: Residential schools, the 60’s Scoop, rape of Indigenous women and children in residential schools and other institutions.

- Forced economic dependence. Examples: restricted access to hunting grounds, loss of habitat for food sources, inability to negotiate “Nation-to-Nation” as legally “wards of the state,” treaty rights not honoured.