Chapter 4: Key Ethical Issues within Law Enforcement

4.7 Use of Force Philosophy Theory and Law

Introduction

One of the most contentious issues facing peace officers, including police, corrections and sheriffs, is the use of force on citizens being arrested or citizens under an officer’s custodial care. Officers who use force are subject to scrutiny in the following ways:

- Court. In the courts (criminal and civil), officers who use force, where it is determined the force is unreasonable given the totality of the circumstances, are subject to criminal charges or lawsuits in civil court. The force used by the officers does not have to result in injury to the subject for charges or civil action to result. The key is if the use of force is determined to be unreasonable given the totality of the circumstances. Charges in criminal court can range from first degree murder to assault. In civil court, officers may be held accountable for their actions and be found liable for the damages they have caused.

- Internal Investigations. Officers may be subject to investigations conducted by their own police department’s investigators within the department’s professional standards unit. The investigation will determine whether a criminal offence has been committed, but also whether the officer has breached the Police Act and/or departmental policy and procedures. When it has been determined that an officer has breached the Police Act or a departmental policy, the consequences may range from a verbal reprimand to suspension to termination of employment.

- Media Coverage. With the prevalence of cameras in the community, officers’ actions will often be captured on video. Even the most legitimate use of force can appear to be ugly, unnecessary, overly violent, and troubling. Video coverage of a use of force event is often biased and misrepresentative of the whole incident, or has been taken out of context. The November 6, 2014 incident, in which a Vancouver police officer broke a car window of a motorist to arrest the driver, was portrayed as excessive use of force against a driver for a driving violation. The police state that the window was broken after the driver failed to comply with the officer, and the officer broke the window to allow him to make a drug arrest in a potentially dangerous situation. The depiction by the media was somewhat balanced, including views from the police. However, the dissenting view in the article suggested that this type of action would eventually lead Canada to become a ‘totalitarian’ country. The officer’s picture was presented in the media, regardless of the final findings of the investigation into the levels of force the officer used. While media is an excellent vehicle for accountability, officers must be mindful that their actions will be publicized and ensure that they appear in a positive light, exercising proper discretion, control, and minimal use of force.

Other Officers. Officers who use excessive force will often find themselves the subject of a complaint by another officer who witnessed the use of force action. Contrary to the perspective of many outsiders to law enforcement, officers will report and initiate a formal complaint against other officers who use excessive force. Instead of formally reporting the officer, other officers who witness excessive force may choose not to work with the officer or advise other officers not to work with the officer. While this is not a desirable outcome, officers using excessive force must be aware that other officers are scrutinizing their conduct, and that the repercussions can range from facing criminal charges to being ostracized.

History of Force in a Sovereign State

The use of force is an unfortunate but necessary component of state governance. Without the ability of the state to use force legitimately, the state would fall into anarchy or, as Hobbes suggests, a state of nature. Force should only be used by the state in a limited fashion and in limited circumstances. Max Weber observed that the state should be the only source that uses force legitimately, and that the use of force must be a tool available for the state to ensure it survives (Waters, 2015). Weber suggests that there is a need for violence to be used against citizens periodically by the state in order for a sovereign state to ensure order (Waters, 2015).

Nozick (1974) concurs, suggesting that the state must claim monopoly on the legitimate use of force and the ability to punish those who use force illegitimately. In the end, for a state to function, force is expected to be used against the citizens of that state from time to time. The inevitable tension arises when trying to determine the actions that constitute legitimate force as opposed to illegitimate force.

The police use force at times as part of the social contract in which force is required to ensure peace. As citizens, it is ironic that we expect the use of force to be used at times to ensure peace and keep us from a state of nature, however, we collectively agree that there are times in which force will be used against anyone who threatens the peace, or who has victimized someone else. The consequences of not allowing the government, and by extension the police, to create and execute laws, would be a society that would be, as Locke describes “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” (Hobbes, 1950, p. 104). However, the costs of the social contract can at times lead to abuse of authority, in which the contract is abused on behalf of the government and police. Governments, and, in particular, the police are in a position under the social contract theory to abuse this trust under the guise of protecting society, and must be overseen by accountability measures to ensure that the force used is appropriate and not excessive. Force, therefore, must be used against citizens only when appropriate and with the consent of society as a whole. In support of the notion of social contract theory, Sir Robert Peel’s nine principles include the necessity to recognize that the use of force by the police is at times necessary. While Peel’s idea was to have a non-military force keep public order, it was necessary to account for the need to use force when necessary. Peel recognized that force must be a last resort, and used only to the minimum required to achieve police objectives.

The issue with Peel’s ideas is the subjective nature determining the action considered minimal force. Police officers in Canada differ from officers in the United States and the UK. Officers in the USA are confronted on a daily basis with a culture that considers the second amendment (Amendment 11: ‘A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed’) a sacred right. Interpretation of this amendment entitles Americans to possess firearms for lawful purpose. In the United States, gun possession is common, and police must be mindful that many persons they deal with may be in possession of a gun. In the UK, gun ownership is uncommon, and police do not expect to encounter a person in possession of a gun; as a result, the level of force they use on a day-to-day basis is expected to be lower than that used by their American counterparts.

Canadian police officers’ use of force would fall somewhere between the UK and the US. Canadian police officers are required to be diligent when interacting with citizens, while remaining cognizant that there are fewer guns in Canada than the US, but more than in the UK.

In using force, officers are provided with a range of tools that are at times controversial. Each of these tools must be used sparingly, and only when deemed necessary against subjects who pose threats to themselves or others. Conducted energy weapons, more commonly referred to as Tasers, are an example of a weapon used by police officers that has garnered much controversy. The issue of ‘creepage’ is a concern. This is the notion that, when officers are given and trained in a compliance tool, they tend to use it too liberally, and only once there is official follow up in a judicial inquiry do they become more judicious in the use of the weapon. We also saw this happen when OC, or pepper spray, was introduced. The use of such tools increases in frequency. This trend is prevalent, until there is official oversight admonishing the liberal use of the tool. The use of Tasers, in cases in which the subject is not a threat to the officer or to another person, constitutes torture, as defined by UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. As such, Tasers cannot be used to modify subject behavior; for example, a Taser should not be used when a subject is loudly expressive and angry. Only when the officer feels the subject is a threat and there are no other lesser means available should the Taser be deployed.

A police officer is inherently at risk of being the victim of violence, and the state has a responsibility to minimize the risk of violence. Likewise, police officers in democratic nations have rights as employees and as individuals, and as such they are entitled to do what they must to ensure their safety (Smith, 2009).

Hicks (2004) further attributes the abilities of police in modern democracies to use lethal force as per the ancient traditions of the ‘Just War Doctrine’ (jus ad bellum), which “was utilized to draw a moral boundary between those wars deemed appropriate and necessary and those uses of force deemed morally reprehensible.” (Hicks,2004: 256). Nations considering waging a just war must abide by the following criteria, according to Hicks (2004: 258):

‘(a) competent authority, indicating the need for a sovereign entity to wage war versus a single individual; (b) just cause, which incorporates the proportionality between the just cause and the means of pursuing it; (c) just intent, of which the ultimate aim is peace; (d) last resort, indicating an absence of the availability of other means of resolving the conflict; and (e) reasonable hope of success, a requirement that any morally just conflict must have a semblance of hope for achieving a peaceful resolution.’

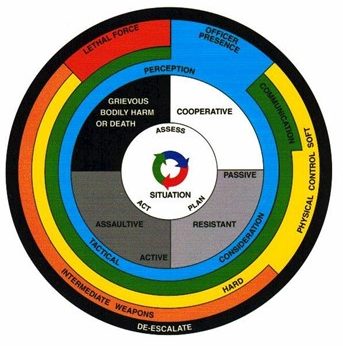

These criteria closely align with the use of force continuum developed within the use of force models that officers in the USA must adhere to. Hicks (2004) feels that force is necessary only when it can be considered just, and thus provides the moral underpinnings that enable war. The requirements for a just war are therefore similar in nature to use of force models that are used by police officers. While Canada does not have a Use of Force Continuum, Canada has a National Use of Force Framework that contains the National Use of Force Model (graphic).

Use of Force Theory and Background

Police officers in Canada have a common law duty to protect life and property. To fulfill this duty, they must at times use force; to not use force to protect life is a dereliction of duty that may result in the officer being charged under the Police Act or under the Criminal Code. While the use of force is not expressly sanctioned under common law, it includes an understanding that force may at times be required.

Police officers in Canada are also authorized to use force by federal statute, provincial statute, and departmental policy and procedure. The theory of use of force is guided by the National Use of Force Framework.

History

Graphic models describing use of force by officers first began to appear in the 1970s in the United States. These early models depicted a rather rigid, linear-progressive process, giving the impression that the officer must exhaust all efforts at one level prior to being allowed to consider alternative options. A frequent criticism of these early models was that they did not accurately reflect the dynamic nature of potentially violent situations, in which the entire range of subject behaviour and police force options must be constantly assessed throughout the course of the interaction.

In Canada, use of force models first began appearing in the 1980s. As part of a comprehensive use of force strategy, Ontario developed a provincial use of force model in 1994; some provinces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police followed suit shortly thereafter.

In 1999, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) endorsed an initiative involving a proposal to develop a national use of force model. In April of the same year, use of force experts and trainers from across Canada met at the Ontario Police College to create one model encompassing the best theory, research and practice for officers’ use of force. The model would be dynamic, support officer training, and facilitate professional and public understanding of officer use of force.

Core Values of the Use of Force Framework

The use of force framework revolves around a series of core principles with which all strategies, tactics and protocols must align. For example, any new tactic developed by use of force experts for officer safety must align with these values. The following values form the framework of the use of force model:

- The primary responsibility of a peace officer is to preserve and protect life.

- The primary objective of any use of force is to ensure public safety.

- Police officer safety is essential to public safety.

- The National Use of Force Model does not replace or augment the criminal, civil and case law; the law speaks for itself.

- The National Use of Force Model was constructed in consideration of (federal) statute law and current case law.

- The National Use of Force Model is not intended to dictate policy to any agency.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms clearly establishes that everyone has certain basic rights. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person, and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. Police officers are duty-bound to adhere to this Charter. However, to implement the mandate given to police officers within the limits set by law, it may become necessary for an officer, in some circumstances, to breach certain rights and individual liberties. Further, while engaged in the duties of policing, such as maintaining law and order, preventing crime, and protecting the public and/or officers themselves, police officers may be called upon to use force.

Canadian Society specifically acknowledges that in certain circumstances police officers are justified, on reasonable grounds, to use the appropriate level of necessary force in order to apply or execute the law. The officer is protected by law, as long as his or her actions are justifiable, and that the use of force remains in accordance with the law, human rights, professional ethics, and organizational and social values.

The National Use of Force Model

The National Use of Force Model (NUFM) was developed to assist in the training of police officers, and as a reference when making decisions and explaining officers’ actions with respect to the use of force. The model does not justify an officer’s actions; rather it identifies to officers the steps they must take to ensure that the actions they take are appropriate and measured. The use of force model is a tool that assists officers in knowing what level of force is appropriate.

Situation:

With every situation, an officer must do three things, before, during, and after the incident is concluded:

Assess: The officer must consider all elements of the situation. He/she needs to know the nature of the call, the suspect(s) involved, if he/she has backup available, what his/her physical abilities are, what the terrain at the location will be like, weather conditions, and so on.

Plan: The officer must formulate an action plan, bearing in mind that all situations are dynamic and constantly changing. Remember, every action has a reaction, so contingency plans must also be considered.

Act: Once on scene, the officer must put his/her plan into action.

It is important to remember that oftentimes officers must assess, plan, and act in a fraction of a second, as in the case of a spontaneous assault on the officer.

Subject Behaviour

The level of force that officers use is contingent upon the subject’s behavior. Subject behavior is categorized in the following levels, ranging from complete cooperation to potentially lethal acts:

Cooperative: This type of subject is referred to as “yes people” because oftentimes seeing the police, or a simple gesture or request to leave will achieve voluntary compliance.

Passive Resistance: Subjects displaying this type of behavior do not do anything to hinder the police, but they also do not do anything to help the police. They may simply become dead weight and are typically seen at sit-in type protests.

Active Resistance: Subjects who actively resist will typically pull arms away from controlling officers, run away, hold onto fixed objects, and brace themselves in doorways or “turtle” by pulling their arms into their chest area, resisting officers’ attempts to straighten the arms.

Assaultive: Assaultive subjects will strike or kick at officers. They may spit, swear, or yell threats at officers and display various pre-assaultive cues that signal a possible physical assault on the officer, including, but not limited to:

- ignoring the officer;

- repetitious questioning;

- aggressive verbalization;

- emotional venting;

- refusing to comply with lawful request;

- ceasing all movement;

- invasion of personal space;

- adopting an aggressive stance; and

- hiding.

Grievous Bodily Harm/Death: Subjects in this category are attacking the officer with intent to injure or kill the officer, with or without weapons. This is the highest and most dangerous level of subject behavior and may result in the subject’s death.

Response Options

Officers have five response options available to them. It is important to remember that, while these are not levels of force, each category of response options has levels of force, ranging from implied to lethal force.

Officer Presence: There are many elements of officer presence, including the officer’s appearance in uniform, his/her perceived level of fitness, size, sex, number of officers, available equipment, etc. Included in this category are perception (all officers see a given situation uniquely) and tactical considerations (any available options to confront the situation, see below).

Communication: This category includes verbal and non-verbal communication; once the communication commences, it should continue throughout the incident.

Physical Control: Physical control is sub-divided into two categories: soft and hard. Soft physical control includes joint locks and manipulations, and takedowns. Hard physical control techniques include strikes, stuns, kicks, and neck restraints. All techniques in this category are typically performed with empty hands, and were formerly referred to as Empty Hand Control Tactics. These techniques range from implied to deadly force in context.

Intermediate Weapons: These “gadgets” that are available to police officers include: Conducted Energy Weapons, OC Sprays and other chemical agents, batons, impact energy weapons (ARWEN, bean bag, etc.), vehicles, weapons of opportunity, noise/flash diversionary devices, and the list goes on. As with other response options, levels of force in this category range from implied to deadly force.

Lethal Force: This category includes all of the other options available in the preceding categories, as well as the various firearms available to the police.

Perception and Tactical Considerations

Perception and Tactical Considerations are two separate factors that may affect the officer’s overall assessment. Because they are viewed as interrelated, they are graphically represented in the same area on the model. They should be thought of as a group of conditions that mediate between the inner two circles (Subject Behavior and Response Options) and the responses available to the officer.

The mediating effect of the Perception and Tactical Considerations circle explains why two officers may respond differently to the same situation and subject. This is because tactical considerations and perceptions may vary significantly from officer to officer and/or agency to agency. Two officers, both faced with the same tactical considerations, may assess the situation differently and therefore respond differently, because they possess different personal traits or have dissimilar agency policies or guidelines. Each officer’s perception will directly impact their own assessment and subsequent selection of tactical considerations and/or their own use of force options.

Perception

How an officer sees or perceives a situation is, in part, a function of the personal characteristics he or she brings to the situation. These personal characteristics affect the officer’s beliefs concerning his or her ability to deal with the situation. For various reasons, one officer may be confident in his or her ability to deal with the situation, and the resulting assessment will reflect this fact. In contrast to this, another officer, for equally legitimate reasons, may feel that the situation is more threatening and demands a different response. The following list includes factors unique to the individual officer, which interact with situational and behavioral factors to affect how the officer perceives and ultimately assesses and responds to a situation.

Factors that may be unique to the individual officer include but are not limited to:

- strength/overall fitness;

- personal experience;

- skill/ability/training;

- fears;

- gender;

- fatigue;

- injuries;

- critical incident stress symptoms;

- cultural background; and

- sight/vision.

Tactical Considerations

An officer’s assessment of a situation may lead to one of the following tactical considerations. Conversely, these same factors may impact an officer’s assessment of a situation.

- disengage and consequences**;

- officer appearance;

- uniform and equipment;

- number of officers;

- availability of backup;

- availability of cover;

- geographic considerations;

- practicality of containment, distance, communications;

- agency policies and guidelines; and

- availability of special units and equipment: canine, tactical, helicopter, crowd management unit, command post, etc.

** Note: An officer’s primary duty is to protect life and preserve the peace, however, when a situation escalates dangerously or when the consequences of continued police intervention seriously increase danger to anyone, the option to disengage may be considered appropriate. It is also recognized that, due to insufficient time and distance or the nature of the situation, the option to disengage may be precluded. If the officer determines the option to disengage to be tactically appropriate, the officer may consider disengagement with the goal of containment and consideration of other options such as seeking alternative cover, waiting for back-up, specialty units, etc.

The National Use of Force Model (NUFM) represents the process by which an officer assesses, plans and responds to situations that threaten public and officer safety. The assessment process begins in the center of the model with the Situation confronting the officer. From there, the assessment process moves outward and addresses the Subject Behavior and the officer’s Perceptions and Tactical Considerations. Based on the officer’s assessment of the conditions represented by these inner circles, the officer selects from the use of force Response Options contained within the model’s outer circle. After the officer chooses a response option s/he must continue to Assess, Plan and Act to determine if his or her actions are appropriate and/or effective, or if a new strategy should be selected. The whole process should be seen as dynamic and constantly evolving until the Situation is brought under control.

Authority to use force separates law enforcement officials from other members of society, and the reasonable use of force is central to every officer’s duties. The National Use of Force Model provides a framework that guides the officer in that duty.

Risk Assessment

An officer uses a risk assessment process to choose a response option. In order to choose the appropriate level of force for the situation before them, an officer must continue risk assessment throughout the situation. Observing only the demonstrated behavior of the subject and any related threat cues may not always be enough to justify using a particular level of force. There may be other times when valuable risk assessment information can be gathered and analyzed, prior to responding.

Stages of Risk Assessment

Risk Assessment should include two factors that officers must take into consideration:

- The likelihood someone or something might be hurt or damaged.

- Whether the police officer should intervene given the seriousness of the harm or damage that appeared imminent.

These are often difficult decisions, and the more adept the officer is at assessing risk, the more readily and appropriately they will respond under urgent circumstances.

Assessing the risk the officer may be exposed to during a call may begin very early in the evolution of the call.

- The officer should gather as much information as possible when the call is first received.

- The who, what, when, where and why of the call.

- Continue while enroute to the call.

- Upon arrival at the scene.

- During the officer’s approach while at the scene.

- While entering onto the immediate scene.

- While in the interior of the scene.

- While exiting the scene.

- While handling prisoners at the scene and in a jail setting.

The officer’s assessment of the risk will constantly evolve as more information is received. The closer to the scene the officer gets, the better their assessment may be. While on scene they must continue to assess the risk. If they have controlled the risk, they must maintain control with the effective method. They must not afford the subject the opportunity to re-escalate. Even while exiting the scene, the officers should monitor the possible risks that may occur from bystanders or associates. In some instances, the officer(s) may be afforded very little initial risk assessment information. Spontaneous attacks, by their nature, afford the officers very little initial risk assessment opportunities.

Legal Justification for the Use of Force

Officers may have plenty of operational discretion, however in use of force, discretion is limited by the criminal code. An officer’s ethical values, in relation to use of force, must closely align with the criminal code and the legal parameters set out. If the officer’s values do not align, the officer is destined for either legal consequences for excessive use of force or injury for not using the appropriate level of force. The law is very clear regarding the limits placed on an officer’s use of force and the legal consequences for officers who use excessive force. The use of force must satisfy the following two tests. It must be:

- Subjectively reasonable (based on the officer’s genuine thoughts, feelings and beliefs). Here the officer is given some leeway, in that they may have mistakenly used force against an unarmed subject in the belief that the subject was armed. This may be because the subject appeared to be reaching for a gun in their pocket after acting in a suspicious manner. The courts may believe that this was subjectively reasonable.

- Objectively reasonable (facts that would convince an ordinary reasonable person that the officer acted reasonably). Here the courts may compare the officer against what would be expected of a reasonable person. In this way the courts determine whether or not the actions are consistent with those of a reasonable person.

What the courts actually require is for judges to apply the “doppelganger test.” Here, a judge will “go” with the officer from the time the officer was first sent to the place where the incident took place, and consider that officer’s training and experience, to determine if the officer acted reasonably. The judge must then consider what a reasonable officer with the same training and experience as the officer who took action would have done. This is significantly different from a judge considering what he or she would have done.

The discretion police have regarding the use of force is controlled by law. The primary authorization in law that allows police officers to legally use force on a person is contained in Section 25 of the Criminal Code. It reads as follows:

25. (1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law

(a) as a private person,

(b) as a peace officer or public officer,

(c) in aid of a peace officer or public officer, or

(d) by virtue of his office,

is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose.

(2) Where a person is required or authorized by law to execute a process or to carry out a sentence, that person or any person who assists him is, if that person acts in good faith, justified in executing the process or in carrying out the sentence notwithstanding that the process or sentence is defective or that it was issued or imposed without jurisdiction or in excess of jurisdiction.

(3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm [1] (Grievous bodily harm means serious hurt or pain. In determining a defense under this section the jury must be directed to the circumstances as they existed at the time that the force was used, keeping in mind that the officer could not be expected to measure the force used with exactitude) unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservation of any one under that person’s protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

(4) A peace officer, and every person lawfully assisting the peace officer, is justified in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm to a person to be arrested, if

(a) the peace officer is proceeding lawfully to arrest, with or without warrant, the person to be arrested;

(b) the offence for which the person is to be arrested is one for which that person may be arrested without warrant;

(c) the person to be arrested takes flight to avoid arrest;

(d) the peace officer or other person using the force believes on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the purpose of protecting the peace officer, the person lawfully assisting the peace officer or any other person from imminent or future death or grievous bodily harm; and

(e) the flight cannot be prevented by reasonable means in a less violent manner.

(5) A peace officer is justified in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm against an inmate who is escaping from a penitentiary within the meaning of subsection 2(1) of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, if

(a) the peace officer believes on reasonable grounds that any of the inmates of the penitentiary poses a threat of death or grievous bodily harm to the peace officer or any other person; and

(b) the escape cannot be prevented by reasonable means in a less violent manner.

Police officers are required to discharge various duties authorized by legislation, such as preserving life and protecting property, preserving the peace, enforcing the law and preventing crime. Under Section 25(1) of the Criminal Code of Canada, police must satisfy three elements to justify the use of force:

- Be “required or authorized” by law to do “anything” in the “administration or enforcement” of the law.

- The police officer must act on reasonable grounds.

- The police officer can only use “as much force as is necessary” for the purpose in question.

Additionally, the Criminal Code contains the following sections dealing with the use of force, not only by peace officers, but also by members of the public:

Section 27 – Prevention of a crime

Section 30 – Prevention of a breach of the peace

Section 31 – Actual breach of peace

Section 32 – Suppressing a riot

Section 34 – Self-defense against an unprovoked assault

Section 35 – Self-defense in case of aggression (property)

Section 43 – Correction of a child by force

Section 45 – Surgical operations

When considering if the use of force can be justified under law, legal and effective methods of force occur when:

- the method is reasonable;

- it is necessary; and

- it is not overly aggressive under the circumstances presented.

In order for police to use force to control a subject, three elements MUST exist.

- A – Did the suspect have or reasonably appear to have the ABILITY to cause injury or death to the officer or others?

- I – Did the suspect demonstrate INTENT? Did words and/or actions lead the officer to believe the suspect had the intent to cause injury or death to the officer or others?

- M – Did the suspect have the MEANS to deliver the perceived threat?

If the suspect demonstrates the above noted elements, the officer is justified in using the force option most appropriate to control the suspect. There are several considerations that a police officer must be aware of when controlling the suspect, such as:

- Was there a lower level of force available to gain control?

- Did or could the officer identify he or she as a police officer?

- Did or could the officer provide the suspect(s) the opportunity to de‑escalate his/her level of resistance towards the officer? (A warning) There is an onus on the officer, if the situation allows, to provide the opportunity to de‑escalate. If the suspect de‑escalates, the member must de-escalate their use of force.

- Did the officer identify the proper risk before intervening accordingly?

- Was the subject isolated? What would the officer hit if the officer missed the suspect?

If the officer(s) involved cannot reasonably articulate the reason(s) for their use of force actions, Section 26 of the Criminal Code (excessive force) may apply:

26. Everyone who is authorized by law to use force is criminally responsible for any excess thereof, according to the nature and quality of the act that constitutes the excess.

Theory Meets Practice and Case Law – Subject Behaviour

Subject behavior can be displayed overtly through physical acts of aggression and/or violence toward others, or covertly through gestures, changes in posture, verbal statements, states of intoxication, inattentiveness, feigned compliance, and the list goes on.

A guiding principle in the use of force that officers follow when classifying subject behavior is that if the officer detects two or more pre-assaultive cues, the officer can intervene with force prior to an overt physical assault by the subject. To justify his/her actions as self defense in a civil action, the officer must prove two elements:

- The circumstances warranted defensive action.

- That the force used was not excessive.

When judging the level of force used by an officer, case law anticipates that the use of force is not to be measured to a “nicety” and that reasonableness “fails to be determined in light of the circumstances and not through the lens of hindsight”. What this means is that hindsight is not to be used by the trier of fact in determining the reasonableness of an officer’s use of force. While these are both important points, special consideration ought to be given to the second point. Those who will judge the use of force actions of the police: lawyers, judges, supervisors, media, peers, family, and the public – generally forget or simply are not aware of this standard. This can be referred to as the “would have, could have, should have” principle.

We see the hindsight principle being abused more and more with the availability of video recordings. Members involved in force-related incidents usually provide duty reports and/or statements without the benefit of having seen video of the incident, and they are only required to answer questions about their actions and corresponding statements during a frame-by-frame review and analysis of the video. Often the first opportunity for officers to see the video is at trial, and their testimony may conflict with their initial reports and statements.

In a recent report published in the Force Science News, Dr. Bill Lewinski asserts that officers should be allowed to review video footage of their critical incident and conduct a walk-through of the scene prior to giving their official statement of account. Lewinski says, “After a high-stress experience, such as a major force confrontation, an officer’s memory of what happened is likely to be fragmentary at best,” and added, “An incident is never completely recorded in memory.”

According to Dr. Lewinski’s research into force-related encounters and memory recall, “The average person will actually miss a large amount of what happened in a stressful event and, of course, will be completely unaware of what they did not pay attention to and commit to memory.”

Compounding the problem, a participant or witness, “…may unintentionally add information in their report that was not actually part of the original incident,” Lewinski explained – not in a plot to deceive, but rather in a humanly instinctive effort to fill in frustrating memory gaps.

Timing of the interview is a major factor because an officer’s version of an incident will vary, depending on whether his/her statement is taken before, after, or without a walk-through or a viewing of a videotape of the incident. The most enriched, complete, and factually accurate version of a high-stress encounter is most likely to occur after a walk-through and/or after the officer has had at least one opportunity to view an available video of the incident.”

Ideally, Lewinski believes, a video review should be permitted before an involved officer gives his/her official statement.

Dr. Lewinski cautions that relying solely on video of a critical incident may be misleading. He cited the following reasons to support his research conclusions:

- Video cameras generally record only a portion of an incident and are bereft of the context of the event.

- Video is a 2-dimensional representation of an incident from a particular perspective and tends to distort distance and other aspects associated with depth of field.

- Generally, video does not faithfully record light levels and does not represent what a human being in the incident would perceive.

- A video does not present the incident as viewed through the officer’s eyes.

- Video cameras recording at less than 10 frames per second can leave out significant aspects of an incident that occur at speeds faster than that.

Allowances for Misconceptions

Police officers arresting a suspect are even afforded the privilege of misjudging the degree of force necessary to affect their purpose during the exigencies of the moment. It has also been determined in case law that it is both unreasonable and unrealistic for officers to use the least amount of force which might successfully achieve their objective, as this would result in unnecessary danger to the officer(s) and others. Case law confirms that injuries suffered by subjects as a result of a peace officer’s use of force do not necessarily establish the use of excessive force.

The use of force is to be judged on a subjective-objective basis. Police actions should not be judged against a standard of perfection, but according to the circumstances as they existed at the time that the force was used.

Use of Force on Persons Held in Custody

As long as the force is reasonably necessary, a constable holding a person in custody is legally authorized to use force to the same extent as a constable who seeks to place a person in custody.

An officer acting on reasonable grounds who is charged with maintaining lawful custody of a subject may use force to return that subject to their cell if they refuse to comply with the operation procedures of the prison.

Authorization for Use of Mechanical Restraints

A peace officer who lawfully arrests a subject is entitled to secure his/her prisoner using mechanical restraints to handcuff or bind the subject. The restraint must be performed reasonably and the officer(s) involved must articulate their reasons for the use of restraints.

Supreme Court

Recently, the Supreme Court of Canada, in Wood versus Shaeffer (2013 SCC71), ruled that a police officer’s notes are to be written immediately after the incident and without discussion with a lawyer. Supreme Court Justice Michael Moldaver, on behalf of the majority residing justices, wrote:

Permitting officers to consult with counsel before preparing their notes runs the risk that the focus of the notes will shift away from the officer’s public duty toward his or her private interest in justifying what has taken place. This shift would not be in accord with the officer’s duty.

Applying the SCC rationale in BC, it appears that this decision prevents officers from specifically demanding a right to counsel prior to completing their notes, particularly as there is no specific statutory entitlement to counsel during a professional standards investigation interview (in BC). However; the SCC ruling specifically states:

nothing … prevents officers who have been involved in traumatic incidents from speaking to doctors, mental health professionals, or uninvolved senior police officers before they write their notes.

Articulation of the Use of Force

There are seven crucial elements that an officer who is involved in a use of force encounter should record in their notes. Each element has several questions that must be addressed objectively to fully assist in articulating the use of force. They include:

1. Scope of Employment

One of the basic points that must be proven by officers involved in a force-related incident is whether or not they were in the lawful execution of their duty and had reasonable grounds to arrest or detain the subject(s) implicated. If excessive force can be proven, the officer’s actions can be considered illegal, and s/he could be liable for criminal and/or civil litigation and/or disciplinary action under the Police Act. Therefore, it is important that the involved officer(s) clearly articulate their reasonable grounds for contacting the subject and their use of force.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

What was the work assignment?

- What was the date, time, and location of the incident?

- Were they in uniform (describe: Patrol, ERT, K9, etc.) or plain clothes (describe)?

- Where were they when dispatched to the incident?

- What was the nature of the assignment or on-view activity of related persons?

- What were they told and by whom?

- What did they observe?

- What was their role in the incident and who assigned them that role?

- Who reported the incident and what did they report?

- Did they identify themselves as a police officer?

2. Severity of the Crime

It is important that an officer have all the vital information about the severity of the crime to enable a safe and proper approach to the scene. To properly assess the reasonableness of an officer’s actions in a force-related encounter, it is necessary to articulate what was known at the time of the incident. Likewise, if the offence is minor in nature, the officer should consider the ramifications of using force for a minor infraction.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- What specific subject behavior was observed?

- What were they told that led them to believe a crime was about to occur or had occurred?

- What were the elements of the crime?

- If the alleged crime was violent in nature, what threat did they perceive to the officer or others?

- Prior to the actual use of force, were they aware if the subject had a history of violence or weapons?

- If so, how did they learn this information (history with the subject, dispatch, other officers, etc.)?

- Did they believe that the subject had access to weapons?

- If so, how was this determined?

- Were the subject’s actions or behavior connected to criminal activity?

- Were there reasonable grounds to believe that the subject’s actions posed a real threat of Grievous Bodily Harm or Death to the officer or another?

- If so, how was this determined?

3. Level of Force Used

The level of force used by a police officer must be subjectively and objectively reasonable. Whenever reportable force is used by an officer, it must be thoroughly documented in the officer’s notebook. Officers are also obligated to complete a report called a ‘Subject Behavior – Officer Response Report’.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- What was the specific type and amount of force used?

- Why?

- Did the officer have other reasonable force options available?

- Did the officer try these other reasonable force options?

- If not, why were they not tried?

- Specifically, what did the subject do that caused the officer to use force?

- Once under control, did the officer handcuff the subject?

- Did another officer assist in the use of force, or after the force was used?

- If so, who?

- Were the handcuffs double-locked to prevent tightening?

- Who double-locked the handcuffs?

- Did the officer tell the subject that s/he was under arrest?

- If not, who did?

- Did the officer know the subject was lawfully arrestable?

- How did the subject refuse to submit to the arrest?

- Did the officer use special restraints to control the subject after arrest?

- If so, what were they?

- Is the officer trained in that specific restraint device?

- If so, how recently was the officer certified and by whom?

- If not, what were the exigent circumstances that prompted the officer to choose that restraint device?

4. Warnings

Warnings are considered an alarm, signal or admonition of a person to stop what is presumed to be unlawful or unwanted behavior. Warnings are reasonable and, when appropriate and reasonable to do so, should be given to subjects and by-standers.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- Was a warning given?

- Provide a description of the specific warning (to whom, how many times, specifics, etc.).

- Did the officer attempt Crisis Intervention De-escalation (CID) Techniques?

- If yes, what was the degree of effectiveness?

- If no, why not?

- Was the officer’s warning consistent with department policy?

- Were there any known barriers to the subject’s understanding of the warning (language, hearing loss, background noise, etc.)?

- Was the warning tape recorded?

- Were other officers aware of the officer’s warning?

- Was the officer aware of other officers’ warnings?

5. Nature of the Crime

In order to show that the officer’s level of force was subjectively and objectively reasonable, the officer must articulate what he or she knew at the time of the force-related encounter, based on the totality of the circumstances. The officer’s state of mind and facts that were perceived, known, or told to the officer are important. The nature of crime dictates the appropriate force response option.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- Is the location of the force-related encounter described as a business, residential area, park, school, open area or another type?

- What were the environmental conditions in the area at the time of the force-related encounter (weather, lighting, footing, terrain, background noise, other parties present, etc.)?

- Was the area of the force-related incident considered to be a high crime area?

- Can this be corroborated?

- How many subjects were involved in the incident?

- Did the officer know the subject(s)?

- How did the officer know the subject(s)?

- Was the officer aware of or did he or she suspect the presence of weapons at the scene?

- What was the known or suspected crime the officer was investigating?

- Was it a violent crime?

- Was anyone injured?

- If so, who, how, and can the officer describe the severity of the injury?

- Was the suspect armed, suspected of being armed or known to be prone to violence?

6. Officer’s State of Mind

Under current Canadian law, the officer’s use of force is not to be judged with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, but on the totality of the circumstances of the incident, using the objective standard and including the facts that would convince an ordinary, reasonable person that the officer acted appropriately. Finally, the officer can only use information known to the officer prior to the officer’s use of force in the officer’s articulation of the why the officer did what the officer did.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- What training relevant to the scope of the officer’s duties (including this incident response) did the officer receive?

- Describe any similar experiences the officer has had that can relate to the officer’s response to this incident.

- Did the officer identify themselves as a police officer?

- Provide details of why the officer felt threatened, fearful and that the officer’s safety or that of others was in jeopardy.

- Did the officer see a weapon?

- How many subjects were present?

- What led the officer to believe that the subject(s) posed a threat of Grievous Bodily Harm or Death to the officer or others (known, perceived, learned)?

- What was the subject’s state of mind?

- Did the subject appear to be under the influence of alcohol, drugs, or both?

- Did the subject appear to be an Emotionally Disturbed Person (EDP)?

- Did the subject appear to be in a state of Excited Delirium (ExDS)?

- What was the subject’s sex, perceived age, physical size, and perceived abilities (martial arts, military, etc.)?

- According to the National Use of Force Model, what subject behaviors were demonstrated (Cooperative, Passive Resistance, Active Resistance, Assaultive, Grievous Bodily Harm or Death)?

- Explain the noted behavior(s) in detail.

- Did the subject(s) pose a tactical advantage that adversely affected the officer’s or another person’s safety?

- What force options did the officer employ to resolve the situation?

- For each force option used, can the officer describe the effect(s) on the subject(s)?

- Was tactical repositioning considered or employed?

- If not, why?

7. Medical Care

Any subject that is injured as a result of an officer’s intervention using force has the absolute right to medical assessment and treatment, when it is safe and reasonable to provide it. Simply, the officer has a duty to care for those under the officer’s control. The officer should report and document all circumstances surrounding the need for medical care of the subject(s) as a result of the force-related encounter.

The following questions should be considered by the involved officer(s):

- Did the officer receive any injuries attributable to the force-related encounter?

- Who caused the injuries?

- What is the nature and extent of the officer’s injuries?

- Did the officer require medical treatment or hospitalization for injuries?

- Was the officer aware of any subject injuries prior to the officer’s use of force?

- If so, what was the nature and extent of the injuries?

- Did the officer’s application of force result in any injury to the subject?

- If so, which force option?

- What was the nature and extent of the injuries caused by the officer’s application of force?

- Once the subject(s) and scene were under control, were the injured parties provided first aid?

- Was PAS summoned?

- If so, by whom?

- Is the officer aware whether anyone else was injured as a result of the subject’s actions?

- If so, what was the nature and extent of the injuries?

- Was PAS summoned?

- If so, by whom?

- Who, if any, of the injured parties went to the hospital?

Conclusion

The detail that officers are required to use to articulate their use of force is extensive. In the past, legal counsel was provided to police prior to providing written details of the force-related incident. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, police are no longer afforded this opportunity.

Officers employing force on subjects resulting in serious injury will experience a great deal of mental trauma. Care should be taken that the involved officers provide detailed notes and duty reports that fully articulate the nature and scope of the incident and their reasonable attempts at a non-violent resolution. In some cases, a non-violent resolution cannot be achieved; it is for these situations that this guide is intended.

Above all, remember that if the officer has been involved in a traumatic incident, nothing prevents the officer from speaking to doctors, mental health professionals, or uninvolved senior police officers before the officer writes their notes.

Media Attributions

- The National Use of Force Model © the RCMP Use of the Conducted Energy Weapon (CEW) report is a copy of the version available at https://www.crcc-ccetp.gc.ca/en/archived-rcmp-use-conducted-energy-weapon-cew#figure1.