Special Diets, Allergies, Intolerances, Emergent Issues, and Trends

18 Food Allergies and Intolerances

This section focuses on food allergies and intolerances, which are areas of great concern in the food service industry. Bakers must pay close attention to how they accommodate food allergies and intolerances in their products, and may need to offer alternatives such as gluten-free baking.

Allergies and Allergic Reactions

Currently, about seven million Canadians self-identify as having a food allergy. Food and other allergies are on the rise, and many Canadians may have a reaction to certain foods but do not know which component in these foods triggers an allergic response.

It is the immune system that reacts to certain foods. An “allergic reaction occurs when the immune system produces antibodies to a substance, called an allergen, which is present in our diet or environment” (Grosvenor, Smolin, & Bedoya, 2014). The most common food allergies that Canadians suffer from are triggered by wheat, nuts (including tree nuts and peanuts), milk, eggs, mustard, seafood, sesame, soy, and sulphites.

Food Intolerances and Food Sensitivities

The terms food intolerances and food sensitivities can be confusing as some sources use them interchangeably, while others claim that food intolerance allows some people to eat a small amount of the food without having a reaction. Health Canada defines the terms as follows:

- A food intolerance is a food sensitivity that does not involve the individual’s immune system. Unlike food allergies, or chemical sensitivities, where a small amount of food can cause a reaction, it generally takes a more normal sized portion to produce symptoms of food intolerance. While the symptoms of food intolerance vary and can be mistaken for those of a food allergy, food intolerances are more likely to originate in the gastrointestinal system and are usually caused by an inability to digest or absorb certain foods, or components of those foods. For example, intolerance to dairy products is one of the most common food intolerances. Known as lactose intolerance, it occurs in people who lack an enzyme called lactase, which is needed to digest lactose (a sugar in milk.) Symptoms of lactose intolerance may include abdominal pain and bloating and diarrhea.

- A food sensitivity is an adverse reaction to a food that other people can safely eat, and includes food allergies, food intolerances, and chemical sensitivities.

- Chemical sensitivities occur when a person has an adverse reaction to chemicals that occur naturally in, or are added to, foods. Examples of chemical sensitivities are reactions to: caffeine in coffee, tyramine in aged cheese and flavour enhancer monosodium glutamate. (Health Canada, 2007b)

Allergies can trigger anaphylactic reactions in which the immune system strongly reacts to a particular protein or irritant. Such life-threatening reactions require immediate medical attention. Additional information on severe allergic reactions and on how to minimize risks can be found on the Health Canada web page Food allergies and gluten-related disorders.

People, who are sensitive to certain foods can also have reactions to food additives, such as monosodium glutamate (MSG), a flavour enhancer. Many food additives claim to make food more palatable, safer, longer lasting, flavourful, and better tasting, as well as enhance its nutritional value (Grosvenor, Smolin, & Bedoya, 2014). Consumers who have food sensitivities, food intolerances, or food allergies need to be extra vigilant when purchasing processed or semi-processed food products because many food additives or flavours are exempt from labelling if they fall under the government exemption standard (see List of Permitted Additives).

Food allergens, however, must be labelled as such. Sulphites, for example, are on the top-ten list of priority food allergens. They may be added to foods in the form of “potassium bisulphite, potassium metabisulphite, sodium bisulphite, sodium dithionite, sodium metabisulphite, sodium sulphite, sulphur dioxide and sulphurous acid. These can also be declared using the common names sulfites, sulphites, sulfiting agents or sulphiting agents” (Health and Nutrition, 2012d).

Many Canadians suffer from an autoimmune disorder that can cause celiac disease and must follow a gluten-free diet. Others who are faced with digestive problems, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), may benefit from a gluten-free diet. Health Canada (2008, July 18) states over 300,000 Canadians may have celiac disease, and the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation (CDHF) claims only 110,000 get diagnosed. Other sources also confirm that this disease is not easily diagnosed, leaving a large number of Canadians wondering if they too have celiac disease. The CDHF further states more than 20 million Canadians suffer from digestive disorders and over 25,000 Canadians die of digestive diseases each year.

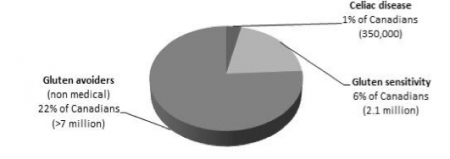

Figure 5 illustrates how many Canadians are gluten avoiders, thus confirming that the popularity of gluten-free diets is based on a lifestyle choice. Gluten-free is the fastest-growing market segment addressing food intolerances and will continue to increase over the coming years. People who suffer from celiac disease may be eligible to have their medical expenses reimbursed for the incremental cost of gluten-free products (see Celiac Disease Foundation, Tax Deductions).

Additionally, many Canadians suffer from diabetes and require sucrose substitutes in their diet. Every year, more than 60,000 Canadians are diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, a type of diabetes where the body produces insulin, a hormone that helps in regulating the glucose (sugar) in the blood, but cannot use it properly. Type 2 diabetes may be slowed or even prevented by monitoring the intake of daily sugars, whereas Type 1 diabetes cannot be prevented. People with Type 1 diabetes do not produce any insulin. People with either type of diabetes can benefit from using a sugar substitute in their diet. However, consumption of a sugar substitute must remain within safety limits. The Government of Canada has approved many sugar substitutes.

Wheat-free/Gluten-free

Gluten is found in wheat, such as whole wheat, kamut, rye, triticale, barley, oats, and other non-stream grains (see the Grains and Flours chapter in the Understanding Ingredients for the Canadian Baker open textbook). Recent studies suggest that people with celiac disease may have some tolerance to eating oats. Health Canada has published a review and it can be found under Celiac Disease and the Safety of Oats.

Gluten-free or non-gluten grains include rice, corn, millet, and pseudo grains such as amaranth, buckwheat, and quinoa. Many food products may contain gluten, such as deli meats, salad dressings, soup mixes, and many processed and premade meals. Some teas may contain malt, which is made from barley. Other food products and candies may contain gluten (Fenster, 2008). For example, unexpected sources of wheat include Werther’s Original Hard Candies (and other Werther candies), coffee substitutes, soy sauce, and pasta sauces. A number of chocolate bars may also contain wheat (gluten). Glucose is widely used in gluten-free baking, but bakers must pay attention to its origin as it can be made from wheat or corn.

Anecdotal information from bakers based on their practical experiences, coupled with findings of some research, suggest long fermentation processes in sourdough breads can “cut gluten”; in other words, long fermentation decreases the concentration/intensity of gluten. Read this CBC article about sourdough breadmaking, which includes interesting facts and suggests that breads manufactured through a long fermentation process may be acceptable for some people with digestive intolerances. This article does not suggest, however, that people with celiac disease can freely eat sourdough breads. However, the study “Safety for Patients With Celiac Disease of Baked Goods Made of Wheat Flour Hydrolyzed During Food Processing” (2011) [PDF] by Luigi Greco and his team shows promising results for the use of food-grade sourdough lactobacilli, which have an effect on gluten during an extended fermentation. More scientific studies are needed to examine gluten in depth to determine whether gluten concentration can be reduced to the point where people with celiac disease could consume these gluten-containing breads safely. Until such time, gluten-free products are the best choice for those suffering from celiac disease.

Long Descriptions

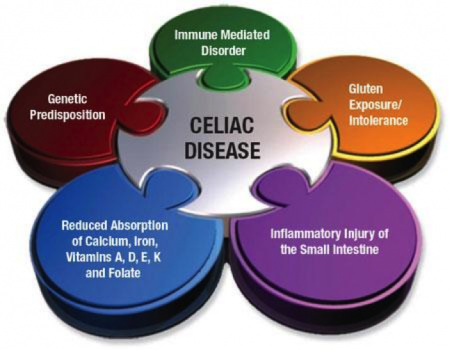

Figure 4 long description: Celiac disease depicted as a six-piece puzzle, with a round piece labelled “celiac disease” at the centre and five pieces attached to it like the petals of a flower. The five pieces are genetic predisposition; immune mediated disorder; gluten exposure/intolerance; inflammatory injury of small intestine; and reduced absorption of calcium, iron, folate, and vitamins A, D, E, and K. [Return to Figure 4]

Figure 5 long description: A pie chart showing the consumers of gluten-free products by type. The largest segment is non-medical gluten avoiders, which is 22% of Canadians at over 7 million people. The second-largest segment is for those with gluten sensitivity, which is 6% of Canadians at 2.1 million people. The smallest segment is for those with celiac disease, which is 1% of Canadians at 350,000 people. [Return to Figure 5]

An autoimmune disorder of the small intestine that is caused by a reaction to a gluten protein found in wheat, and to similar proteins found in other common grains such as barley and rye