The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?

6 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. One technique that effective writers use is to begin a fresh paragraph for each new idea they introduce.

Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. One paragraph focuses on only one main idea and presents coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. To create longer assignments and to discuss more than one point, writers group together paragraphs.

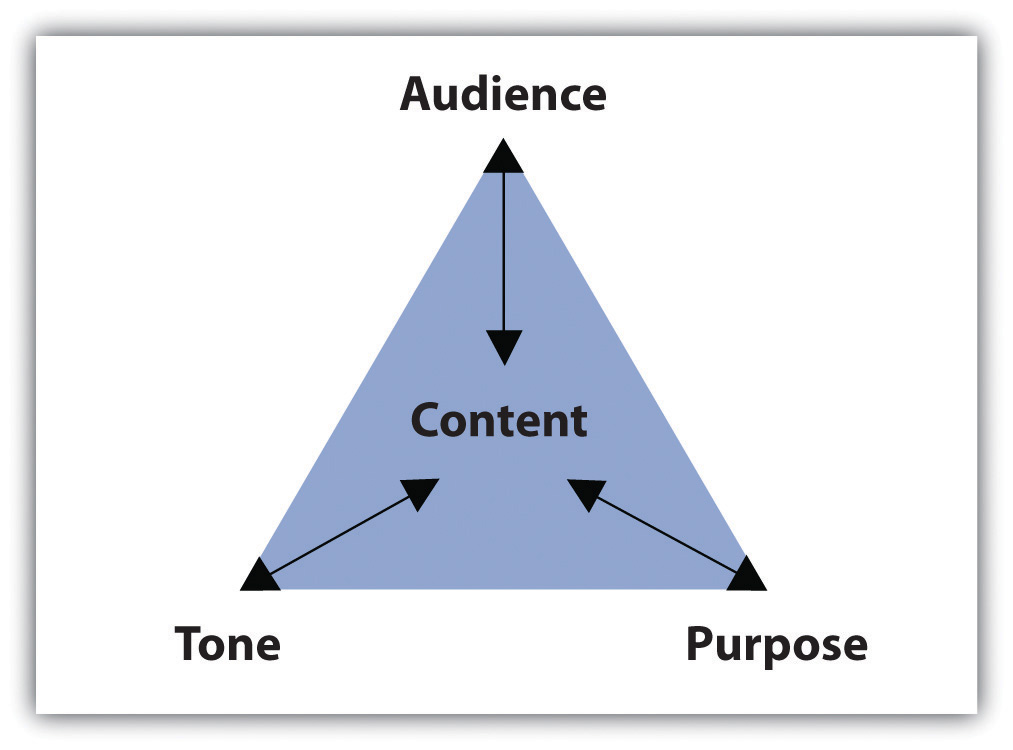

Three elements shape the content of each paragraph:

- Purpose. The reason the writer composes the paragraph.

- Tone. The attitude the writer conveys about the paragraph’s subject.

- Audience. The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what the paragraph covers and how it will support one main point. This section covers how purpose, audience, and tone affect reading and writing paragraphs.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write a particular document. Basically, the purpose of a piece of writing answers the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing fulfill four main purposes:

- to summarize,

- to analyze,

- to synthesize, and

- to evaluate.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure. Because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read.

Eventually, your instructors will ask you to complete assignments specifically designed to meet one of the four purposes. As you will see, the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of the paper, helping you make decisions about content and style. For now, identifying these purposes by reading paragraphs will prepare you to write individual paragraphs and to build longer assignments.

Summary Paragraphs

A summary shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials. You probably summarize events, books, and movies daily. Think about the last blockbuster movie you saw or the last novel you read. Chances are, at some point in a casual conversation with a friend, coworker, or classmate, you compressed all the action in a two-hour film or in a two-hundred-page book into a brief description of the major plot movements. While in conversation, you probably described the major highlights, or the main points in just a few sentences, using your own vocabulary and manner of speaking.

Similarly, a summary paragraph condenses a long piece of writing into a smaller paragraph by extracting only the vital information. A summary uses only the writer’s own words. Like the summary’s purpose in daily conversation, the purpose of an academic summary paragraph is to maintain all the essential information from a longer document. Although shorter than the original piece of writing, a summary should still communicate all the key points and key support. In other words, summary paragraphs should be succinct and to the point.

Here is a report on youth alcohol consumption:

According to the Monitoring the Future Study, almost two-thirds of 10-grade students reported having tried alcohol at least once in their lifetime, and two-fifths reported having been drunk at least once (Johnston et al, 2006x). Among 12th-grade students, these rates had risen to over three-quarters who reported having tried alcohol at least once and nearly three-fifths who reported having been dunk at least once. In terms of current alcohol use, 33.2 percent of the Nation’s 10th graders and 47.0 percent of the 12th graders reported having used alcohol at least once in the past 30 days; 17.6 percent and 30.2 percent, respectively, reported having had five or more drinks in a row in the past 2 weeks (sometimes called binge drinking); and 1.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively, reported daily alcohol use (Johnston et al. 2006a).

Alcohol consumption continue to escalate after high school. In fact, eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds have the highest levels of alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence of any age group. In the first 2 years after high school, lifetime prevalence of alcohol use (based on 2005 follow-up surveys from the Monitoring the Future Study) was 81.8 percent, 30-day use prevalence was 59 percent, and binge-drinking prevalence was 36.3 percent (Johnston et al, 2006b). Of note, college students on average drink more than their noncollege peers, even though they drink less during high school than those who did not go on to college (Johnston et al, 2006a.b: Schulenberg and Maggs 2002). For example, inn 2005, the rate of binge drinking for college students (1 to 4 years beyond high school was 40.1 percent, whereas the ate for their noncollege age mates was 35.1 percent.

Alcohol use and problem drinking in late adolescence vary by sociodemographic characteristics. For example, the prevalence of alcohol use is higher for boys than for girls, higher for White and Hispanic adolescents than for African-American adolescents, and higher for those living in the north and north central United States than for those living in the South and West. Some of these relationships change with early adulthood, however. For example, although alcohol use high school tends to be higher areas with lower population density (i.e., rural areas) than in more densely populated areas, this relationship reverses during early adulthood (Johnston et al., 2006 a,b). Lower economic status (i.e., lower education level of parents) is associated with more alcohol use during early high school years; by the end of high school, and during the transition to adulthood, this relationship changes, and youth from higher socioeconomic background consume greater amounts of alcohol.

A summary of the report should present all the main points and supporting details in brief. Read the following summary of the report written by a student:

Brown et al. inform us that by tenth grade, nearly two-thirds of students have tried alcohol at least once, and by twelfth grade this figure increases to over three-quarters of students. After high school, alcohol consumption increases further, and college-aged students have the highest levels of alcohol consumption dependence of any age group. Alcohol use varies according to factors such as gender, race, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

Some of these trends may reverse in early childhood. For example, adolescents of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to consume alcohol during high school years, whereas youth from higher socioeconomic status are more likely to consume alcohol in the years after high school.

Notice how the summary retains the key points made by the writers of the original report but omits most of the statistical data. Summaries need not contain all the specific facts and figures in the original document; they provide only an overview of the essential information.

Analysis Paragraphs

An analysis separates complex materials in their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. The analysis of simple table salt, for example, would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride, which is also called simple table salt.

Analysis is not limited to the sciences, of course. An analysis paragraph in academic writing fulfills the same purpose. Instead of deconstructing compounds, academic analysis paragraphs typically deconstruct documents. An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

Take a look at a student’s analysis of the journal report:

At the beginning of their report, Brown et al. use specific data regarding the use of alcohol by high school students and college-age students, which is supported by several studies. Later in the report, they consider how various socioeconomic factors influence problem drinking in adolescence. The latter part of the report is for less specific and does not provide statistics or examples.

The lack of specific information in the second part of the report raises several important questions. Why are teenagers in rural high schools more likely to deink than teenagers in urban areas? Where do they obtain alcohol? How do parental attitudes influence this trend? A follow-up study could compare several high schools in rural and urban areas to consider these issues and potentially find ways to reduce teenage alcohol consumption.

Synthesis Paragraphs

A synthesis combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Consider the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of the synthesizer is to blend together the notes from individual instruments to form new, unique notes.

The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document. An academic synthesis paragraph considers the main points from one or more pieces of writing and links the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Take a look at a student’s synthesis of several sources about underage drinking:

In their 2009 report, Brown et al. consider the rates of alcohol consumption among high school and college-ages students and various sociodemographic factors that affect these rates. However, this report is limited to assessing the rates of underage drinking, rather than considering methods of decreasing these rates. Several other studies, as well as original research among college students, provide insight into how these rates may be reduced.

One study, by Spoth, Greenberg, and Thurrisi (2009) considers the impact of various types of interventions as a method for reducing alcohol consumption among minors. They conclude that although family-focused interventions for adolescents aged ten to fifteen have shown promise, there is a serious lack of interventions available for college-aged students who do not attend college. These students are among the highest risk level of alcohol abuse, a fact supported by Brown et al.

I did my own research and interviewed eight college students, four men and four women. I asked them when they first tried alcohol and what factors encouraged them to drink. All four men had tried alcohol by the age of thirteen. Three of the women had also tried alcohol by thirteen and the fourth had tried alcohol by fifteen. All eight students said that peer pressure, boredom, and the thrill of trying something illegal were motivating factors. These results support the research of Brown at al. However, they also raise an interesting point. If boredom is a motivating factor for underage drinking, maybe additional after school programs or other community measures could be introduced to dissuade teenagers from underage drinking. Based on my sources, further research is needed to show true preventative measures for teenage alcohol consumption.

Notice how the synthesis paragraphs consider each source and use information from each to create a new thesis. A good synthesis does not repeat information; the writer uses a variety of sources to create a new idea.

Evaluation Paragraphs

An evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday experiences are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge. For example, at work, a supervisor may complete an employee evaluation by judging his subordinate’s performance based on the company’s goals. If the company focuses on improving communication, the supervisor will rate the employee’s customer service according to a standard scale. However, the evaluation still depends on the supervisor’s opinion and prior experience with the employee. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine how well the employee performs at his or her job.

An academic evaluation communicates your opinion, and its justifications, about a document or a topic of discussion. Evaluations are influenced by your reading of the document, your prior knowledge, and your prior experience with the topic or issue. Because an evaluation incorporates your point of view and reasons for your point of view, it typically requires more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills. Thus evaluation paragraphs often follow summary, analysis, and synthesis paragraphs. Read this student’s evaluation paragraph:

Notice how the paragraph incorporates the student’s personal judgment within the evaluation. Evaluating a document requires prior knowledge that is often based on additional research.

TIP: When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs summarize, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Exercise 6.1

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph.

- This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

- During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

- To create the feeling of being gripped in a vice, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theater at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

- The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals will intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration

Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing in Process

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much specific detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. Listen for words such as summarize, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report to help determine a purpose for writing.

Exercise 6.2

Consider the essay most recently assigned to you. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

My assignment:

My purpose:

Identifying the Audience

With an expository essay, since you are defining or informing your audience on a certain topic, you need to evaluate how much your audience knows about that topic (aside from having general common knowledge).

You want to make sure you are giving thorough, comprehensive, and clear explanations on the topic. Never assume the reader knows everything about your topic (even if it is covered in the reader’s field of study). For example, even though some of your instructors may teach criminology, they may have specialized in different areas from the one about which you are writing; they most likely have a strong understanding of the concepts but may not recall all the small details on the topic. If your instructor specialized in crime mapping and data analysis for example, they may not have a strong recollection of specific criminological theories related to other areas of study.

Providing enough background information without being too detailed is a fine balance, but you always want to ensure you have no gaps in the information, so your reader will not have to guess your intention.

- Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

- Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send e-mails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Example A

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Example B

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with her intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own paragraphs, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject. Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics. These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education. Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge. This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations. These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

Exercise 6.3

On your own sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

- Your classmates

- Demographics:

- Education:

- Prior knowledge:

- Expectations:

- Your instructor

- Demographics:

- Education:

- Prior knowledge:

- Expectations:

- The head of your academic department

- Demographics:

- Education:

- Prior knowledge:

- Expectations:

- Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.My assignment:My purpose:My audience:

- Demographics:

- Education:

- Prior knowledge:

- Expectations:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Keep in mind that as your topic shifts in the writing process, your audience may also shift.

Also, remember that decisions about style depend on audience, purpose, and content. Identifying your audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how you write, but purpose and content play an equally important role. The next subsection covers how to select an appropriate tone to match the audience and purpose.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit through writing a range of attitudes, from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just 7 percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelt and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.

Exercise 6.4

Think about the assignment and purpose you selected in exercise 2 and the audience you selected in exercise 3. Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

My assignment:

My purpose:

My audience:

My tone:

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of third graders. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone. The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Exercise 6.5

Match the content in the box to the appropriate audience and purpose. On your own sheet of paper, write the correct letter next to the number.

- Whereas economist Holmes contends that the financial crisis is far from over, the presidential advisor Jones points out that it is vital to catch the first wave of opportunity to increase market share. We can use elements of both experts’ visions. Let me explain how.

- In 2000, foreign money flowed into the United States, contributing to easy credit conditions. People bought larger houses than they could afford, eventually defaulting on their loans as interest rates rose.

- The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, known by most of us as the humungous government bailout, caused mixed reactions. Although supported by many political leaders, the statute provoked outrage among grassroots groups. In their opinion, the government was actually rewarding banks for their appalling behavior.

-

Audience: An instructor

Purpose: To analyze the reasons behind the 2007 financial crisis

Content:

-

Audience: Classmates

Purpose: To summarize the effects of the $700 billion government bailout

Content:

-

Audience: An employer

Purpose: To synthesize two articles on preparing businesses for economic recovery

Content:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Exercise 6.6

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone from exercise 4, generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

My assignment:

My purpose:

My audience:

My tone:

My content ideas:

Text Attributions

- Text under “Identifying the Audience” was adapted from “What are You Writing, to Whom, and How?” in Writing for Success 1st Canadian Edition by Tara Horkoff and a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. Adapted by Allison Kilgannon. CC BY-NC-SA.

- Text also has been adapted from “Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content” in Writing for Success by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution (and republished by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing). Adapted by Allison Kilgannon. CC BY-NC-SA.