Rhetorical Modes

34 Critique

In this chapter, you will develop your critical thinking and analysis skills through examining a critique. The chapter will also provide guiding questions to help you formulate the elements to include in a critique. The self-practice exercises will provide you opportunities to examine more in depth what critiquing entails, and you will have the opportunity to proceed through the stages to develop your own critique.

What is a Critique?

A critique is a written work critically analyzing or evaluating another piece of writing; also known as a review or critical response.

When you see the word critique, the first thing you may think of is to criticize. In actuality, critiques do not need to look only at the negative aspects of a source; they can also focus on the positive components or even have a mix of the positive and negative elements. They are critical response papers analyzing and evaluating an original source, such as the academic journal article you are being asked to use for this assignment.

Exercise 37.1

Read the following short critique, and then come up with a list of elements you believe make this a critique as opposed to an expository paper.

Vetter and Perlstein’s work on terrorism and its future is an excellent basis for evaluating views and attitudes to terrorism before the tragic events of 9/11. Written in 1991, the book provides an objective (but more theoretical) view on what terrorism is, how it can be categorized, and to what ideology it can be linked. Perspectives on Terrorism is a multifaceted review of numerous factors that impact and influence the global development of terrorism; those studying sociology or criminal justice might find ample information regarding the ideological roots and typology of terrorism as a phenomenon and as a specific type of violent ideology that has gradually turned into a dominant force of political change.

Vetter and Perlstein (1991) begin their work with the words “it has almost become pro forma for writers on terrorism to begin by pointing out how hard it is to define the term terrorism.” However, the authors do not waste their time trying to define what terrorism is; rather, they are trying to look at terrorism through the prism of its separate elements, and objectively evaluate the concept of public acceptability of terrorism as a notion. Trying to answer the two critical questions “why surrogate the war?” and “who sponsors terrorism?” Vetter and Perlstein (1991) evaluate terrorism as a unjustifiable method of violence for the sake of unachievable goals, tying the notion of terrorism to the notion of morality.

To define terrorism in its present form it is not enough to determine the roots and the consequences of particular terrorist act; nor is it enough to evaluate the roots and the social implications of particular behavioural characteristics beyond morality. On the contrary, it is essential to tie terrorism to particular political conditions, in which these terrorist acts take place. In other words, whether the specific political act is terrorist or non-terrorist depends on the thorough examination of the social factors beyond morality and law. In this context, even without an opportunity to find the most relevant definition of terrorism, the authors thoroughly analyze the most important factors and sociological perspectives of terrorism, including the notion of threat, violence, publicity, and fear.

Typology of terrorism is the integral component of our current understanding of what terrorism is, what form it may take, and how we can prepare ourselves to facing the challenges of terrorist threats. Vetter and Perlstein (1991) state that “finding similarities and differences among objects and events is the first step toward determining their composition, functions, and causes.” Trying to evaluate the usefulness of various theoretical perspectives in terrorism, the authors offer a detailed review of psychological, sociological, and political elements that form several different typologies of terrorism. For example, Vetter and Perlstein (1991) refer to the psychiatrist Frederick Hacker, who classifies terrorists into crazies, criminals, and crusaders. Later throughout the book, Vetter and Perlstein provide a detailed analysis of both the criminal and the crazy types of terrorists, paying special attention to who crusaders are and what role they play in the development and expansion of contemporary terrorist ideology. Vetter and Perlstein recognize that it is almost impossible to encounter an ideal type of terrorist, but the basic knowledge of terrorist typology may shed the light onto the motivation and psychological mechanisms that push criminals (and particularly crusaders) to committing the acts of political violence.

Perspectives on Terrorism pays special attention to the politics of terrorism, and the role, which ideology plays in the development of terrorist attitudes in society. “Violence or terrorism can be used both by those who seek to change or destroy the existing government or social order and those who seek to maintain the status quo” (Vetter & Perlstein, 1991). In other words, the authors suggest that political ideology is integrally linked to the notion of terrorism. With ideology being the central element of political change, it necessarily impacts the quality of the political authority within the state; as a result, the image of terrorism is gradually transformed into a critical triangle with political authority, power, and violence at its ends. In their book, Vetter and Perlstein (1991) use this triangle as the basis for analyzing the political assumptions, which are usually made in terms of terrorism, as well as the extent to which political authority may make violence (and as a result, terrorism) legally permissible. The long sociological theme of terrorism that is stretched from the very beginning to the very end of the book makes it particularly useful to those who seek the roots of terrorism in the distorted political ideology and blame the state as the source and the reason of terrorist violence.

Reference: Vetter, H.J. & Perlstein, G.R. (1991). Perspectives on terrorism (Contemporary issues in crime and justice). Pacific Grove, CA, USA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

What makes this a critique?

- List three to five elements you think make this a critique.

- Please share with a classmate.

Critique Is Different from Expository Essay

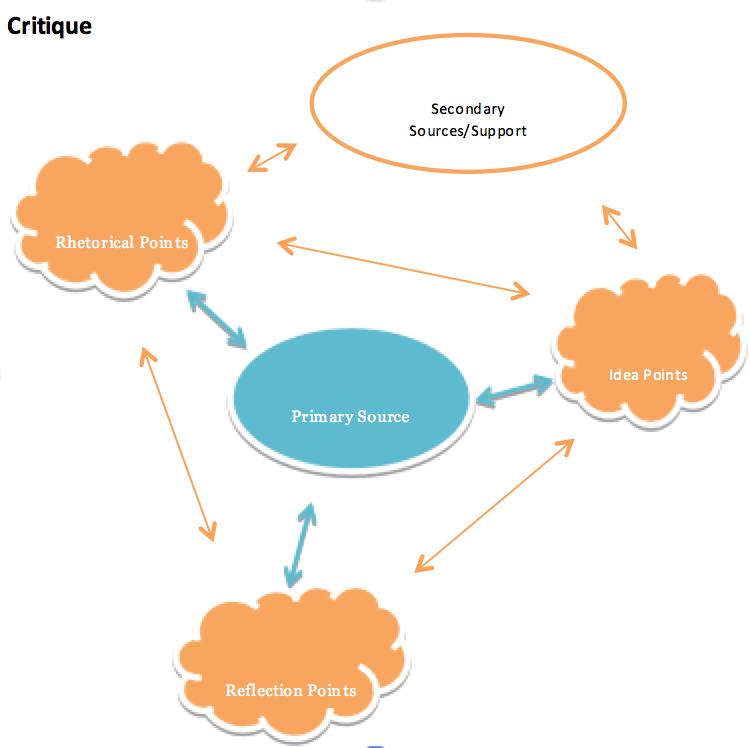

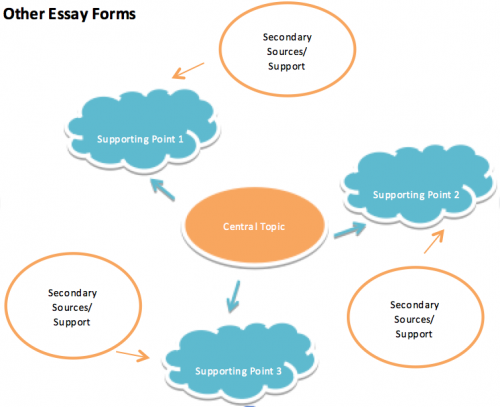

A critique is different from an expository essay, which is a discussion revolving around a topic with multiple sources to support the discussion points. As you can see in Exercise 37.1, depending on the type of critique you are writing, your reference page could include one source only. However, as you may discuss topical ideas within the original source, you may also want to include secondary sources to which you can compare and contrast the original source’s ideas, but you need to always connect your discussion points back to the original source. Figure 37.1: Critiquing versus Other Essay Forms shows visual representations of what a critique structure could look in comparison to another essay, such as one that is expository or persuasive in purpose.

If you look at the mind map for the critique, you can see how all of the discussion points stem from and relate back to the original article and how all of the discussion points can be interconnected. Also, the bubble labelled Secondary Sources/Support shows you can integrate secondary sources to compare and contrast when discussing either rhetorical or idea points. In the second diagram, you can see that the supporting ideas relate to the central topic, but they are extensions of the topic each with their own supporting forms of evidence. There is less emphasis placed on synthesis of ideas, although this is something you can still do when composing this type of essay.

The Purpose of Critiquing

In an academic environment, your instructors will expect you to demonstrate critical thinking skills that go beyond simply taking another person’s ideas and spitting out facts. They will want you to show your ability to assess and analyze any type of information you use; they will also want to see that you have used sources to develop ideas of your own.

Critiquing, or critical analysis, demonstrates you are able to connect ideas, arrive at your own conclusions, and develop new directions for discussion. You are also showing you have strong background knowledge on the topic in order to provide feedback on another person’s discussion on the issue.

Elements of a Critique

Often people go online for to read reviews of services or products. They sometimes make personal choices based on those reviews, such as what movie to go to or which restaurant to eat at. When you ask for a recommendation, the person you are asking will usually give you a brief summary of the experience then break his or her opinion down into smaller aspects—good and bad. For example, imagine you want to visit a new restaurant, and you ask your friend to recommend a place. Here is a sample response:

There is an amazing Japanese restaurant called Mega Sushi at the corner of Main and 12th. The food, atmosphere, and service are great. The food is always excellent, and they have a lot of original creations or spins on traditional Japanese food, but it still tastes authentic. The ingredients are always incredibly fresh, and you never have to worry about ordering the sashimi. The decor is also very authentic and classic, and the entire place is incredibly clean.

The service is generally very good—they even bring you a free sample roll while you wait for your food—but it can be a little slow during the dinner rush because it is such a popular place. Also, the prices are a little high because an average roll costs $15, but for the amazing food you get, it is totally worth it! I love this place!

When you break this example into sections, you can see the first and second sentences give the reviewer’s general opinion of the restaurant; they also summarize the main components the reviewer will cover. The review is then broken into smaller categories or points.

Notice that not all the points covered are positive: while the food and atmosphere are good, the service has both positive and negative aspects but is overall good. Also, the prices are high, but the writer states that people who eat there get good value for their money. Providing a generalized description first, the reviewer introduced the topic to the audience; she then analyzed individual aspects or components of the experience with examples to help convince the audience of her perspective.

Not everyone may have the same positive experience, of course. What if it was someone’s first time at this particular restaurant, and she arrived during the dinner rush feeling very hungry and had to wait a long time for a table? Not knowing how good the food is and that it is worth the wait, she may just leave, so her general impression of the restaurant would probably not be favourable. Whether the experience would be positive or negative would depend on an individual’s personal experience and situation.

Any critique, no matter if it is of a book, an article, or a movie, needs to contain the following elements:

- A thesis: usually a general view of a source.

- Example: In Smith’s (2009) article, he effectively argues his case for the reinstatement of capital punishment in Canada.

- A summary: highlighting the main points presented.

- This would be the same as if you were writing a summary of any source you read.

- Critiquing points: elements the reader (you) have a reaction to when reading the source.

- You will decide on these points based on your reactions and personal preferences using the guiding questions for each of the forms below as suggestions.

Getting Started on Your Critique

Before You Begin Critiquing

As with any source you examine, you need to make sure you have a solid grasp on the ideas presented by the author. Before you start analyzing your source, it is helpful to compose a summary to confirm you understand what the source is all about and that you do not leave out any important points. Remember that if your audience does not have a strong understanding of the overall picture of the source, they may have difficulty following your critique.

Often what we share verbally when summarizing a source highlights the main points of our impression of the material; we capture all the necessary points, but we do so concisely. For Exercise 37.2, you will need to work with a partner to compose a succinct summary of your article.

Exercise 37.2

Part A: Do individually

Scan your article’s abstract (if there is one), introduction, headings, topic sentences, and conclusion.

Read the article in its entirety. Briefly make note of any area you struggle with or have a reaction to. (This will help you later.)

Make notes on what you think the main ideas are.

Compose a short paragraph summarizing your article (75 to 100 words).

Part B: Collaboration–Please complete with a classmate.

- Put your summary aside and do not refer to it for this next part.

- Verbally summarize your article for your partner in 30 to 60 seconds.

- Your partner will need to take very brief notes of the verbal summary you give.

- Switch roles.

Once you have both summarized verbally and taken notes for each other, show the summary paragraph you wrote in Part A to your partner.

- Read the summary paragraph and compare it to the notes you took from the verbal summary.

- Prepare feedback based on the following questions:

- What were the differences between the verbal and written summaries?

- Did the written summary contain anything unnecessary or miss anything important?

- Which one was organized more logically?

- Give both the notes and summary back to your partner, and read your own, asking for clarification if necessary.

- Revise your summary, so you will have a composed paragraph you can insert into your critique later.

- Come up with a working thesis for your paper. What was your overall impression? (You may change or add to this later when you learn more about what to look for when critiquing.)

Later, you will need to decide on one of two formulas to follow when composing your critique. If you choose to use Formula 1, you will need to include an independent summary paragraph, which you have now already completed and may only require a little fine tuning. If you choose Formula 2, you will not include the summary as its own paragraph, but you will need to break it apart when you introduce the points you are going to discuss within the critique.

The following sections will discuss the different critiquing forms and what you can look for when deciding what points you would like to discuss in your critique.

Critiquing Forms and Formulas

Critiquing Forms

Again, critiquing does not mean you are looking only for the negative points in a source; you can also discuss elements you like or agree with in the article. Also, you may generally get a positive impression from the source but have some issues with some aspects for which you can provide constructive criticism—perhaps what the author could have done better, in your opinion, to make a stronger and more effective impact.

There are four critiquing forms on which you can structure your analysis of a source. These are:

- Rhetorical

- Ideas

- Reflection

- Blended

The critiquing elements you will be required to apply to each assignment will vary depending on your instructor’s directions, the purpose of the assignment, and the writer (you).

Guiding questions: rhetorical

Focusing on the rhetorical elements when critiquing means you are looking at the construction elements of a source. Use the following questions as a reference point when you are going through your article to provide you with some focus and help you generate ideas for your paper (not all may be relevant to your article).

- What is the author’s purpose?

- For whom is the author writing? Who is the audience?

- What type of language does the author use? Technical? Straightforward? Too informal?

- How appropriate is the language, sentence structure, and complexity for the intended audience?

- What is the genre, and how has it impacted the writing style?

- How logical/reasonable is the argument?

- What kind of evidence does the author use to support? Is it reputable, relevant, or current, and is there enough?

- To what degree did the author engage or interest the reader in the topic?

- How much bias does the author show, or is the argument presenting multiple points of view?

- How convinced are you by the presentation of ideas?

- Is there anything the author could have done differently to convince you more completely?

- Is there anything about the technical writing style you did or did not like?

- How was the source organized? How may that affect the reader?

Exercise 37.3

In Exercise 37.1, you read your article and were asked to make notations wherever you got caught up by something within the source. Now, look back at those notations, decide which if any relate to the rhetorical guiding questions above, and make brief notes of the relevant rhetorical points in the space below.

If none of your notations matched the questions, read the questions (and your article) again, and then try to answer the questions briefly. At this point you may identify more than two questions; later you will have the opportunity to assess which are your strongest points.

Guiding questions: ideas

Ideas: When discussing the ideas of a source, you are examining the topic presented in the source. You explore how the author’s ideas mesh with your own and state whether you agree or disagree; you are essentially joining the discussion on that topic.

You may find you agree with some parts of the discussion but not others, or you may completely agree or disagree, or you may think the author has great points but does not develop them adequately.

Also, you may want to provide differing points of view from other sources to show you have not just accepted what the first author wrote; you have explored the topic further and will present a thorough discussion in your own critique.

- On which points do I agree or disagree with the author? (Remember, you do not always have to only agree or disagree on all points)

- What new ideas has the author introduced on the topic? How has the author contributed to the field?

- What could the author have done differently to provide a stronger discussion?

- How narrow or broad was the author’s discussion? Did the author consider multiple points of view? Is there anything the author overlooked?

- How do other experts approach a discussion on this topic?

Exercise 37.4

Just as you did in Exercise 37.3, look back to Exercise 37.1 where you made notations whenever you got caught up by something within the source. Decide which if any relate to the idea guiding questions above, and make brief notes of the relevant idea points in the space below.

If none of your notations matched the questions, read the questions (and your article) again and then try to answer the questions briefly. At this point you may identify more than two questions; later you will have the opportunity to assess which are your strongest points.

Guiding questions: reflection

Reflection: By providing a personal reflection on the source, you are being introspective and showing you have thought about how the source affects you personally and connects to your personal experiences, beliefs, and values. In this case, you can give personal observations and experiences as your own forms of supporting evidence; however, you do not want your paper to solely use this type of support because you need more factual evidence to convince your reader. Also, remember to check with your instructor if this is a form you are required to use.

- How does this source connect to your personal experiences or memories?

- What challenges does the source raise when you consider your own personal values and beliefs?

- How does the source confirm your personal values and beliefs?

- What new ideas or insight did the source raise for you?

- How did the source inspire you to do more research on the topic?

Exercise 37.5

Just as you did in Exercises 37.3 and 37.4, look back to Exercise 37.1 where you made notations whenever you got caught up by something within the source. Decide which if any relate to the reflection guiding questions above, and make brief notes of the relevant reflection points in the space below.

If none of your notations matched the questions, read the questions (and your article) again then try to answer the questions briefly. At this point you may identify more than two questions; later you will have the opportunity to assess which are your strongest points.

Guiding questions: blended

Blended: In a blended form, your critique pretty much evolves however you want it to. You can take certain elements from each of the three previous forms: whichever questions are the easiest for you to discuss and are maybe the most interesting for you.

This shows how paying attention to your reactions when you initially read the source is helpful; once you have made note of where and what you reacted to, you can go back each list of guiding questions and decide which best relate to each of your notations.

There are no guiding questions for the blended form because you use you mix and match the questions already provided in the earlier sections.

In a blended critique, you demonstrate an extremely high level of critical thinking ability because you are not only synthesize your ideas with external sources, you also connect personally to one source, external sources, and different forms or aspects of analyzing written works.

Exercise 37.6

Look back at the points you came up with in Exercises 37.3, 37.4, and 37.5. You now need to select the points—at least one from each category—that you feel you can discuss the most thoroughly.

Collaboration

With a classmate, share your points and how you would expand on them.

Ask your partner for any other ways they think you could expand on those points.

Blended Critique: Two Formulas

Once you have chosen a source and used the guiding questions to help generate points to discuss in your critique, you will need to decide how to best organize your ideas. There are two formulas you can apply as a framework when organizing your critique ideas. Remember that although the formulas below show each section as an individual paragraph, you may actually need to create more than one paragraph to fully develop your ideas.

Formula 1

Organizing your critique following this model is fairly straightforward as there is not much overlap between the sections. You may want to choose this formula if you are feeling a little unsure of how to organize your ideas and prefer a more guided structure.

- Introduction

- Attention getter

- Background

- Thesis + author’s last name, publication date, and title of source

- Signposts (including that the next paragraph will be a summary)

- Summary

- Restate author’s name, publication date, and title of source (provides a citation for the paragraph).

- This needs to be brief and include only the points significant to your later discussion.

- If you include too much here, you may end up repeating yourself later.

- Rhetorical

- Give topic sentence explain this paragraph/section will cover rhetorical points

- State point

- Give explanations

- Give examples and make connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations

- Provide concluding statement summarizing rhetorical element discussion

- Ideas

- Give topic sentence explain this paragraph/section will cover idea points

- State point

- Give explanations

- Give examples and make connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations

- Provide concluding statement summarizing idea or topic element discussion

- Reflection

- Give topic sentence explain this paragraph/section will cover reflection points

- State point

- Give explanations

- Give examples and make connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations

- Provide concluding statement summarizing reflection element discussion

- Conclusion

- Restate author’s last name, publication date, and source’s title

- Summarize your discussion points

- Restate your thesis

Formula 2

This model is a little more challenging to stay organized and to not go off on a tangent when you are critiquing; however, it allows you to have much more freedom in how you piece your ideas together.

When you use this formula, it is important to remember to keep referring to the outline you created before writing and to thoroughly develop ideas by connecting one critiquing form to another.

This model differs from Formula 1 because the summary is briefly included in the introduction section, and the discussion points are not divided by critiquing points but rather by topic. That is, multiple critiquing forms are used to develop one topic point. Because this formula is a little more complicated to explain, an example outline is provided for you after the template.

- Introduction

- Attention getter

- Thesis + author’s last name, publication date, and title of source

- Background (this includes the briefest of summaries of the source: one to two sentences only)

- Signposts

- Point 1: A

- Choose one topic to focus on using the guiding questions (one of three forms)

- Give a topic sentence introducing the point

- Restate author’s name, publication date, and title of source (provides a citation for the paragraph)

- Develop point making connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations

- Provide brief concluding sentence for paragraph

- Point 1: B

- Give topic sentence explaining that this paragraph/section connects to or expands on previous paragraph (different form used in previous paragraph)

- Restate author’s name and publication date (provides a citation for the paragraph)

- Develop point making connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations and to previous paragraph

- Provide concluding statement summarizing entire discussion of point 1

- Point 2: A

- Choose one topic to focus on using the guiding questions (one of three forms)

- Give a topic sentence introducing the point

- Restate author’s name and publication date (provides a citation for the paragraph)

- Develop point making connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations

- Provide brief concluding sentence for paragraph

- Point 2: B

- Give topic sentence explaining this paragraph/section connects to or expands on previous paragraph (different form used in previous paragraph)

- Restate author’s name and publication date (provides a citation for the paragraph)

- Develop point making connections relating directly back to section(s) of original source + citations and to previous paragraph

- Provide concluding statement summarizing entire discussion of point 2

- Conclusion

- Restate author’s last name, publication date, and source’s title

- Restate your thesis

- Summarize your discussion points

Formula 2: example

- Introduction

- Attention getter

- Thesis + author’s last name, publication date, and title of source

- Background (this includes the briefest of summaries of the source: one-two sentences only)

- Signposts

- Point 1: Language + Audience (Rhetorical)

- Restate author’s name, publication date, and title of source (provides a citation for the paragraph)

- Give a topic sentence introducing the point

- Develop and explain complexity of language + perhaps: the language is too difficult for the average reader—forcing audience to have to constantly look up words in dictionary

- Explain impact = distracting + annoying

- Use specific examples from source (with citations)

- Point 1: Language + Audience (Reflection)

- Give topic sentence explaining this paragraph/section relates to previous paragraph

- Explain whether or not you are member of intended audience—know this from impact language had on you personally

- Had to look up words; give examples (with citations)

- Could not understand author’s point; give examples (with citations)

- Clearly not part of target audience

- Concluding statement summarizing point discussion from both paragraphs

- Point 2: Topic: Capital punishment (Ideas)

- Give topic sentence explaining this paragraph/section will cover idea point

- State point

- Give explanations

- Give examples relating directly back to section(s) of original source

- Point 2: Topic: Capital punishment (Reflection)

- Give topic sentence explaining this paragraph/section will cover reflection point in relation to your own point of view—maybe personal experience—and topic sentence needs to connect this to previous paragraph

- State point

- Give explanations

- Give examples relating directly back to section(s) of original source

- Concluding statement summarizing point discussion from both paragraphs

- Conclusion

- Restate author’s last name, publication date, and source’s title

- Summarize your discussion points

- Restate your thesis

Hopefully this example helps you to see how Formula 2 allows a lot more flexibility in organizing the discussion points. You can probably also see how easy it would be for the writer to get off topic. The key is to connect the ideas together. This formula definitely shows a greater complexity of thought development and synthesis of ideas, both of which your instructor will appreciate. However, you need to make sure you have a solid formal sentence outline before you begin the writing process, or you may confuse your reader too much for him or her to follow your development.

Exercise 37.7

Choose one of the formulas above and integrate the points you came up with in Exercise 37.6. Narrow those points down—to three or four at most—to help you stay focused and develop those points (as opposed to just giving answers to many of the guiding questions without developing them).

Compose an informal topic outline following which formula above you have chosen to follow.

Exercise 37.8

Now expand on the informal topic outline you created in Exercise 37.7. If you have chosen to use Formula 1, you can insert the summary you composed in Exercise 37.2.If you have chosen to use Formula 2, you will need to separate the summary you composed in Exercise 37.2 into topical discussion points for each paragraph. You will then use these separate points to provide context for each discussion point.

Remember to start integrating specific examples from your source. Make sure you note the page numbers for later when you need to add citations (you will learn this next week).

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from “Being Critical” in Writing for Success 1st Canadian Edition by Tara Horkoff and a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. Adapted by Allison Kilgannon to remove, reorder, and reformat some of the content. CC BY-NC-SA.

Media Attributions

- Figure 37.1 & 37.2 © Tara Horkoff are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.