Group Communication, Teamwork, and Leadership

40 Group Life Cycles and Member Roles

Groups are dynamic systems in constant change. Groups grow together and eventually come apart. People join groups and others leave. This dynamic changes and transforms the very nature of the group. Those who are in leadership positions may ascend or descend the leadership hierarchy as the needs of the group, and other circumstances, change over time.

Group socialization involves how the group members interact with one another and form relationships.

Group Life Cycle Patterns

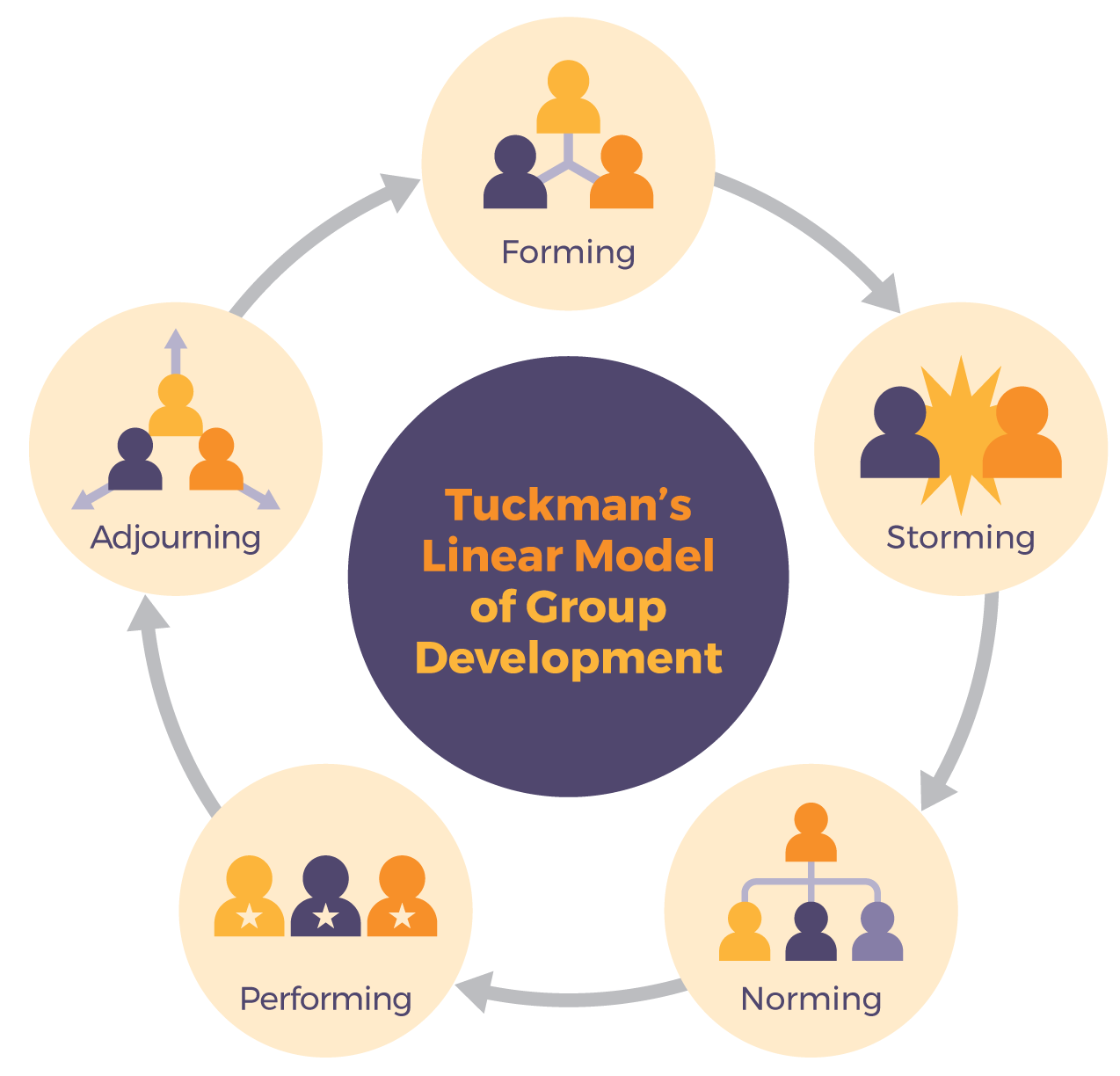

In order to better understand group development and its life cycle, many researchers have described the universal stages and phases of groups. While there are modern interpretations of these stages, most draw from the model proposed by Bruce Tuckman (1965). This model, shown in Figure 43.1, specifies the usual order of the phases of group development as a cycle, and allows us to predict several stages we can anticipate as we join a new group.

Tuckman (1965) describes the five stages as follows:

- Forming: Members come together, learn about each other, and determine the purpose of the group.

- Storming: Members engage in more direct communication and get to know each other. Conflicts between group members will often arise during this stage.

- Norming: Members establish spoken or unspoken rules about how they communicate and work. Status, rank, and roles in the group are established.

- Performing: Members fulfill their purpose and reach their goal.

- Adjourning: Members leave the group

Tuckman begins with the forming stage as the initiation of group formation. This stage is also called the orientation stage because individual group members come to know each other.

If you don’t know someone very well, it is easy to offend. Each group member brings to the group a set of experiences, combined with education and a self-concept. You won’t be able to read this information on a nametag, but instead you will only come to know it through time and interaction.

Since the possibility of overlapping and competing viewpoints and perspectives exists, the group will experience a storming stage, a time of struggles as the members themselves sort out their differences. There may be more than one way to solve the problem or task at hand, and some group members may prefer one strategy over another.

The norming stage is where the group establishes norms, or informal rules, for behaviour and interaction. Who speaks first? Who takes notes? Who is creative, who is visual, and who is detail-oriented? We are not simply a list of job functions, and in the dynamic marketplace of today’s business environment you will often find that people have talents and skills well beyond their “official” role or task. Drawing on these strengths can make the group more effective.

The norming stage is marked by less division and more collaboration. The level of anxiety associated with interaction is generally reduced, making for a more positive work climate that promotes listening.

Ultimately, the purpose of a work group is performance, and the preceding stages lead to the performing stage, in which the group accomplishes its mandate, fulfills its purpose, and reaches its goals. To facilitate performance, group members can’t skip the initiation of getting to know each other or the sorting out of roles and norms, but they can try to focus on performance with clear expectations from the moment the group is formed.

In the adjourning stage, members leave the group. The group may cease to exist or it may be transformed with new members and a new set of goals. Like life, the group process is normal, and mixed emotions are to be expected.

Watch the following 2 minute video Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing: Bruce Tuckman’s Team Stages Model Explained

Life Cycle of Member Roles

Just as groups go through a life cycle when they form and eventually adjourn, so the group members fulfill different roles during this life cycle. These roles, proposed by Richard Moreland and John Levine (1982), are summarized in Table 43.1.

| Potential Member | Curiosity and interest |

|---|---|

| New Member | Joined the group but still an outsider and unknown |

| Full Member | Knows the “rules” and is looked to for leadership |

| Divergent Member | Focuses on differences |

| Marginal Member | No longer involved |

| Ex-Member | No longer considered a member |

Positive and Negative Member Roles

If someone in your group always makes everyone laugh, that can be a distinct asset when the news is less than positive. At times when you have to get work done, however, the class clown may become a distraction. Notions of positive and negative will often depend on the context when discussing groups. Table 11.2 “Positive Roles” and Table 11.3 “Negative Roles” list both positive and negative roles people sometimes play in a group setting (Beene & Sheets, 1948; McLean, 2005).

| Initiator-Coordinator | Suggests new ideas of new ways of looking at the problem |

|---|---|

| Elaborator | Builds on ideas and provides examples |

| Coordinator | Brings ideas, information, and suggestions together |

| Evaluator-Critic | Evaluates ideas and provides constructive criticism |

| Recorder | Records ideas, examples, suggestions, and critiques |

| Dominator | Dominates discussion, not allowing others to take their turn |

|---|---|

| Recognition Seeker | Relates discussion to their accomplishments; seeks attention |

| Special-Interest Pleader | Relates discussion to special interest or personal agenda |

| Blocker | Blocks attempts at consensus consistently |

| Joker or Clown | Seeks attention through humour and distracts group members |

Now that you’ve reviewed positive and negative group member roles, you may examine another perspective. While some personality traits and behaviours may negatively influence groups, some traits can be positive or negative depending on the context.

Just as the class clown can have a positive effect in lifting spirits or a negative effect in distracting members, a dominator may be exactly what is needed for quick action. An emergency physician doesn’t have time to ask all the group members in the emergency unit how they feel about a course of action; instead, a self-directed approach based on training and experience may be necessary. In contrast, a teacher may ask students their opinions about a change in the format of class; in this situation, the role of coordinator or elaborator is more appropriate than that of dominator.

The group is together because they have a purpose or goal, and normally they are capable of more than any one individual member could be on their own, so it would be inefficient to hinder that progress. But a blocker, who cuts off collaboration, does just that. If a group member interrupts another and presents a viewpoint or information that suggests a different course of action, the point may be well taken and serve the collaborative process. But if that same group member repeatedly engages in blocking behaviour, then the behaviour becomes a problem. A skilled business communicator will learn to recognize the difference, even when positive and negative situations and roles aren’t completely clear.

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from “Group Life Cycles and Member Roles” in Communication for Business Professionals – Canadian Edition published by eCampusOntario, which was adapted from Business Communication for Success by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution (and republished by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing). Adapted by Allison Kilgannon. CC BY-NC-SA.

Media Attributions

- Figure 43.1 “Tuckman’s Linear Model of group development” © eCampus Ontario is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

- “Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing: Bruce Tuckman’s Team Stages Model Explained” by MindToolsVideos. Standard YouTube Licence.