Chapter 11. Lifespan Development

Big Picture Models of Lifespan Development

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 7 minutes

Indigenous Connectedness Framework

The Indigenous Connectedness Framework explores Indigenous lifespan development within Indigenous communities, emphasising the role of intergenerational, family, community, environmental, and spiritual connections in wellbeing. It underlines cultural values, knowledge sharing, and collective identity in nurturing individuals and communities. There are five major domains that shape a child’s relational identity.

- Intergenerational connectedness underscores the value of being part of a continuous history and the duty towards future generations. It helps children understand their roots and develop a strong sense of identity linked to their ancestors, enhancing a collective sense of duty and interconnectedness.

- Family connectedness extends to a wide network of biological and spiritual relationships, key to cultural identity and value transmission. It focuses on extended family, especially grandparents imparting knowledge and traditions, reinforcing a sense of belonging and mutual support within the community.

- Community connectedness involves social groups providing a sense of belonging and shaping both individual and collective identities. Through shared celebrations, ceremonies, and communal activities, these connections reinforce community cohesion and support the holistic development of its members.

- Environmental connectedness acknowledges the profound and inseparable relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their natural surroundings. This physical and spiritual bond, underscoring the land’s significance in cultural identity and wellbeing, and teaching children the importance of living in harmony with nature.

- Spiritual connectedness weaves together the various threads of connectedness, integrating mind, body, and spirit in cultural practices and ceremonies. This level of connectedness fosters a deep sense of unity with all beings and the natural world, promoting a collective wellbeing and respect for life’s interdependence.

Spiritual” refers to a connection beyond the physical, involving inner feelings, beliefs, and a sense of belonging to something greater. It encompasses unity with mind, body, spirit, and a bond with the world, including people, nature, and possibly a higher power.

A spiritual connection brings with it an appreciation of the interdependence of all life and a duty to respect the delicate balance of life.

The Indigenous Connectedness Framework offers a holistic perspective on lifespan development within Indigenous communities. By understanding the interactions among intergenerational, family, community, environmental, and spiritual connections, we appreciate the richness of Indigenous cultures and the profound impact of interconnectedness on individuals’ lives. This framework highlights the significance of cultural values, knowledge transmission, and the fostering of collective identity for the wellbeing of Indigenous communities.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

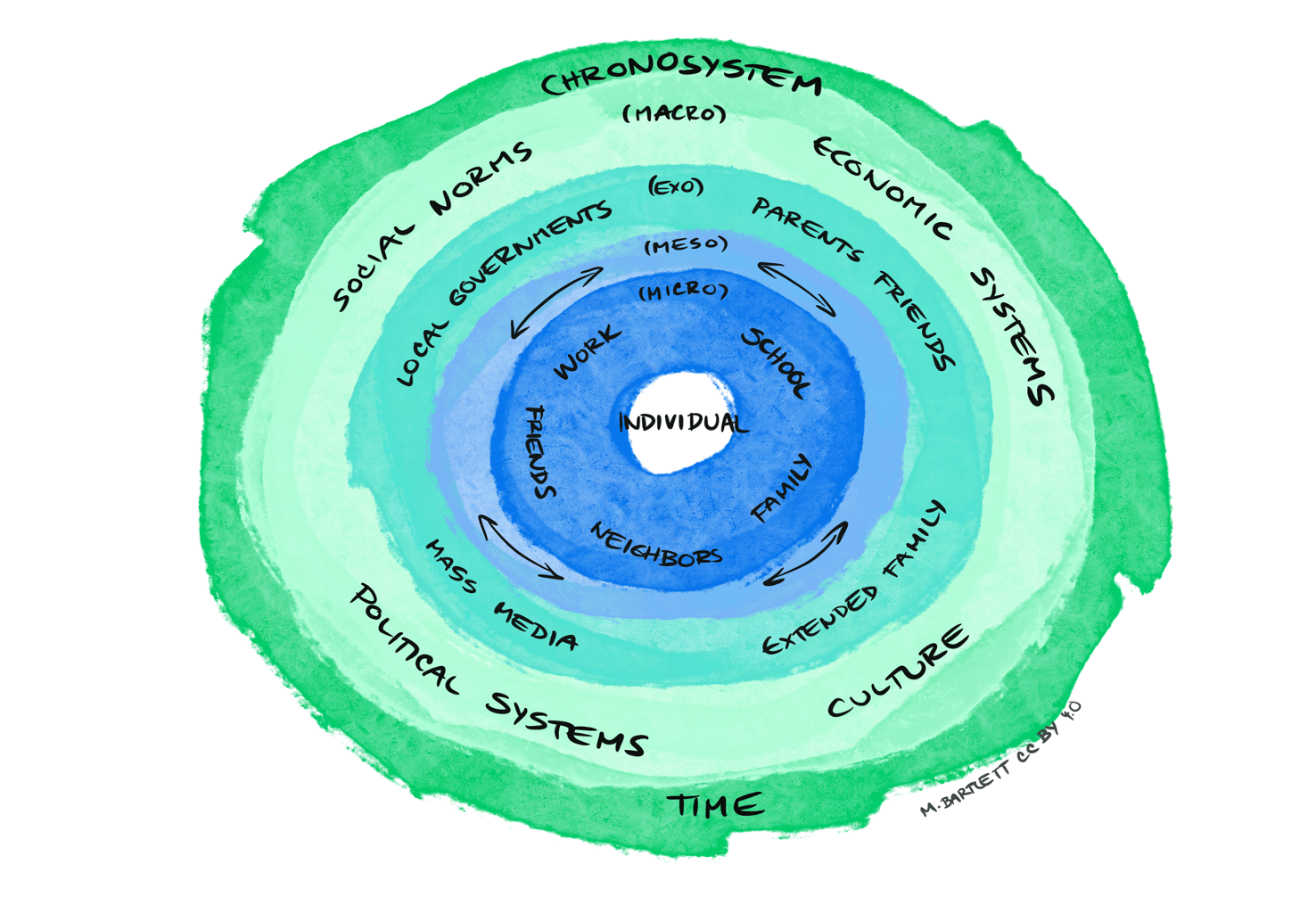

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a framework for understanding human development by illustrating how various environmental systems influence growth throughout a person’s life. This theory identifies five key systems:

- Microsystem — “Me and My Crew”: Directly surrounds the individual, incorporating immediate relationships and activities, such as interactions and interdependence with family, school, and peers. A change in the family, like a divorce, can affect a child’s academic performance and peer relationships.

- Mesosystem — “Web of Relation:”: Encompasses the connections between the microsystems, highlighting how different areas of a person’s life interact, like the relationship between a child’s educators and their parents. Positive mesosystem interactions can enhance a child’s feeling of security and support.

- Exosystem — “Invisible Impact”: Consists of broader social settings that indirectly influence the individual, including parental workplaces and community services. Changes in this layer, such as a parent’s job loss, can indirectly impact the child’s microsystem by altering family dynamics or financial stability.

- Macrosystem — “Cultural Code”: Reflects the overarching cultural values, laws, and societal norms that shape an individual’s development. Cultural expectations around milestones like marriage can influence personal goals and societal participation, affecting one’s self-esteem and life choices.

- Chronosystem — “Time’s Tango”: Incorporates the dimension of time, recognising the impact of life transitions and societal changes on an individual’s development. It includes both external events, such as historical changes, and internal changes, like physiological aging, highlighting how timing affects development.

Bronfenbrenner’s theory emphasises the dynamic interactions between these systems and their collective impact on an individual’s development, underscoring the interconnected nature of human experiences that shape growth from childhood to adulthood.

Conclusion

As we wrap up our exploration of the Big Picture models of lifespan development, we need to remember that development involves interconnected personal, social, historical, and environmental influences as shown in the Indigenous Connectedness Framework and Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. These models challenge us to think beyond conventional boundaries, encouraging a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of human development.

Next

In this next section we will explore several focused perspectives on lifespan development. Specifically we will learn that:

- The famous Clarks’ doll experiment teaches us about the effects of racism on children.

- Vygotsky’s social construction theory teaches us about the necessary conditions for learning.

- Erikson’s psychosocial theory teaches us about how our social lives shape our development.

- Piaget’s stages of cognitive development teach us how we learn to problem-solve.

- Kohlberg’s theory of moral development teaches us how we establish our sense of good and bad, and learn ethical thinking and behaviour.

- Tatum’s racial identity theory teaches us about how people in minority groups develop their racial identity and how we all can step up to anti-racist social action.

- Downing and Rouche teach us the stages of developing a feminist identity and engaging in community action to achieve gender equity.

- Fowler’s stages of spiritual development teach us that humans’ spiritual development includes many back and forth steps and many choices.

We will learn that by examining each of these focused perspectives we increase our understanding of the intricate ways individuals change, grow and interact with their environments as they navigate their developmental paths.

Image Descriptions

Figure LD.4. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory image description: A concentric circle diagram with three levels of circles, as well as text outside of that.

Innermost circle: Individual

2nd circle: (Micro)

- Work

- School

- Friends

- Neighbours

- Family

Third circle (Meso):

Fourth circle (Exo):

- Local Governments

- Parents

- Friends

- Extended Family

- Mass Media

Fifth circle (Macro):

- Social norms

- Economic Systems

- Culture

- Political Systems

Sixth/outermost circle:

- Chronosystem

- Time

Image Attributions

Figure LD.4. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory by Marie Bartlett is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).