Chapter 13. Motivation

What is Motivation?

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 7 minutes

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

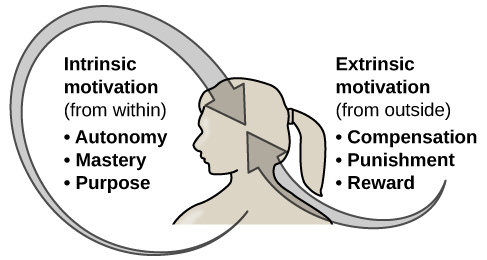

Why do we act the way we do? What drives our choices and behaviours? Motivation is the key to understanding these questions. It’s the force that directs our behaviour towards goals, shaped by our wants and needs. Motivation isn’t just about our biological needs; it also involves intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic motivation comes from within us, driven by personal satisfaction and fulfillment. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is influenced by external rewards or pressures.

Intrinsic motivation is deeply personal. For instance, if you’re in college because you love learning and want to grow as a person, that’s intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is more about external outcomes, like pursuing a degree for a high-paying job or to meet family expectations.

Our motivations often blend intrinsic and extrinsic elements, and this mix can shift over time. The saying, “Choose a job you love, and you’ll never work a day in your life,” captures this idea. However, research shows that this isn’t always straightforward. When we receive extrinsic rewards, like payment, for something we love, it can start to feel more like work and less enjoyable. This phenomenon, known as the overjustification effect, suggests that extrinsic rewards can diminish intrinsic motivation [Deci et al., 1999].

For example, consider Lei, who loves baking (Figure MO.2). Initially, he bakes for fun, but when he starts baking professionally, his motivation changes because now he is baking for external rewards. This shift illustrates how extrinsic rewards can transform an enjoyable activity into a job, altering our intrinsic motivation.

Yet, not all extrinsic rewards undermine intrinsic motivation. Verbal praise, for example, can actually enhance it [Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994]. If Lei receives compliments for his baking, his passion for baking might stay strong. The impact of rewards on motivation depends on their nature and our expectations. Tangible, physical rewards like money can have a more negative effect on intrinsic motivation than intangible, non-physical rewards like praise. Also, if we expect a reward, it can reduce our intrinsic motivation. But if the reward is a surprise, our intrinsic motivation might remain unaffected [Deci et al., 1999].

In educational settings, intrinsic motivation flourishes when students feel respected and part of the classroom community. This sense of belonging can be enhanced by reducing the focus on evaluations and giving students some control over their learning. Challenging yet achievable tasks, coupled with clear reasons for engaging in them, can also boost intrinsic motivation [Niemiec & Ryan, 2009].

Why Talk About Needs in a Chapter on Motivation?

Needs are the basic things that every person must have to live a healthy and satisfying life. These include food, water, shelter, and safety. Imagine you’re playing a video game, and your character needs certain items to survive and move to the next level. In real life, we also have needs that keep us alive and well.

Motivations, on the other hand, are the reasons behind why we do what we do. It’s like having a personal mentor in your mind that encourages you to achieve your goals. These goals can be anything from finding safe affordable housing or making friends, to learning a new skill. Motivation is what pushes you out of bed in the morning to tackle the day ahead.

Why do we talk about needs in a chapter about motivation? Well, it’s because our needs are closely linked to our motivations. Think of it this way: if you’re really hungry (a need), you’re motivated to find something to eat; if you feel unsafe (a need), you’re motivated to find a safe place. Our needs often set the stage for our motivations. They are like the roots of a tree, while motivations are the branches that grow because of those roots.

In psychology, understanding needs is crucial because it helps us figure out what motivates people. By knowing what a person needs, we can better understand why they act in certain ways. For example, if someone is working hard in school, it might be because they have a need for achievement or they’re motivated by the desire to make their family proud.

Instinct as Motivation

Motivation is a complex interaction of internal desires and external influences. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for fostering environments that support healthy, effective motivation in various contexts, from education to the workplace. Let’s now survey some of the many things that can be significant motivators for us humans.

William James (1842–1910) was an important contributor to early research into motivation. James theorised that behaviour was driven by a number of instincts that aid survival (Figure EM.4). From a biological perspective, an instinct is a species-specific pattern of behaviour that is not learned. There was, however, considerable controversy among James and his contemporaries over the exact definition of instinct. James proposed several dozen special human instincts, but many of his contemporaries had their own lists that differed. A parent’s protection of their baby, the urge to lick sugar, and hunting prey were among the human behaviours proposed as true instincts during James’s era. This view that human behaviour is driven by instincts received a fair amount of criticism because learning — not just instinct — shapes all sorts of human behaviour.

Image Attributions

Figure MO.1. Figure 11.7 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure MO.2. Figure 10.3 by Agustín Ruiz as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).