Chapter 1. Introduction

Subdisciplines in Psychology

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 40 minutes

The field of psychology encompasses a wide range of sub-disciplines, each focusing on different aspects of human behaviour and mental processes. This section provides an overview of various specialised areas within psychology. These sub-disciplines collectively contribute to our comprehensive understanding of human nature and behaviour, and the many ways in which they influence our daily lives. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list. It will provide insight into the major areas of research and practice of modern-day psychologists.

- Abnormal Psychology: The study of mental disorders and psychopathology, delving into the causes and treatments of various psychological disorders such as mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders.

- Anti-Racism Psychology: An emerging field, this study focuses on understanding and combating racial prejudice and discrimination.

- Biopsychology (behavioural neuroscience): The study of the biological underpinnings of behaviour and mental processes, including brain structure, neurotransmitters, and the nervous system, often focusing on neural mechanisms of behaviour.

- Clinical Psychology: The diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders, usinge therapeutic interventions to assist individuals in coping with psychological challenges and enhancing well-being.

- Cognitive Psychology: The study of mental processes such as perception, memory, biases and problem-solving, and language, that aims to understand how people think, reason, and make decisions.

- Community Psychology: The study of the influences that foster positive community change and those that break down communities. This field addresses social justice, poverty, and mental health issues through collaborative strategies for empowerment and social transformation.

- Comparative Psychology: The study of the behaviour and cognitive processes of non-human animals.

- Consumer Psychology: The study of consumer behaviour and decision-making processes, which explores the ways in which factors like advertising, branding, and consumer satisfaction influence marketplace choices.

- Counselling Psychology: The study of the ways in which therapies support individuals, families, and groups facing personal and emotional challenges, that focuses on improving mental health and well-being.

- Critical Psychology: The study of the role of power, privilege, and oppression in psychology, which aims to challenge and change oppressive systems both within psychology and in broader society.

- Cross-Cultural Psychology: The comparison of the psychological phenomena across cultures, which aims to identify universal and culture-specific behaviours, and focuses on the ways in which cultural variations influence social behaviour and decision-making.

- Cultural Psychology: The study of the ways in which cultural beliefs, values, and practices shape thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, which examines the impact of culture on perception, cognition, and social interaction.

- Cyberpsychology: The study of the impact of emerging technology, including virtual reality and social media, on human behaviour and mental processes.

- Developmental Psychology: The study of changes and development across the lifespan, including cognitive and moral development, socialisation, and ageing.

- Educational Psychology: The study of the psychological processes involved in learning and education, which examines learning theories and the ways in which individuals acquire new behaviours and skills.

- Engineering Psychology: The application of psychological principles to enhance the design of technology, equipment, and interfaces for optimal human performance and safety.

- Environmental Psychology: The study of the relationship between individuals and their physical environments, which studies the ways in which different settings affect human behaviour and well-being.

- Feminist Psychology: The study of gender, sexism (sex-based discrimination), and patriarchy and their effects on human development and experiences. This discipline includes advocating for gender equity.

- Forensic Psychology: The application of psychological principles to legal and criminal justice systems, which provides expert testimony on psychological factors in legal cases.

- Gerontology (Psychology of Aging): The study of the psychological and social aspects of ageing, which explores topics like successful ageing and memory changes.

- Group Dynamics: The study of how individuals behave in groups and how group processes affect individual behaviour, which examines group cohesion, leadership, and conflict resolution.

- Health Psychology: The study of the psychological factors influencing physical health and well-being, which focuses on stress, behaviour change, and the mind-body connection.

- Human Factors Psychology: The application of psychological principles to designing user-friendly and safe products and systems, considering human abilities and limitations in design and engineering.

- Indigenous Psychology: The study of the unique psychological perspectives, practices, and traditions of indigenous communities, which studies their psychological experiences and well-being.

- Industrial-Organisational Psychology: The application of psychological principles in the workplace, which addresses employee motivation, job satisfaction, and organisational behaviour.

- Media Psychology: the study of the impact of media (e.g., TV, gaming, radio, virtual and augmented reality, etc.) on human behaviour and cognition, including the effects of media violence on aggression.

- Military Psychology: The study of the mental health and well-being of military personnel and veterans, addressing issues like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and combat stress reactions.

- Motivation and Emotion Psychology: The study of the factors driving behaviour and influencing emotional experiences, which studies motivation theories and emotional regulation.

- Multicultural Psychology: The study of the behaviour of individuals in different cultural settings and the ways in which cultural factors influence mental health.

- Music Psychology: The study of the psychological processes involved in music perception and production, and the impact of music on emotions and cognition.

- Neuropsychology: The study of the relationship between brain function and behaviour, which assesses cognitive deficits resulting from brain injuries or neurological conditions.

- Personality Psychology: The study of individual differences in personality traits, behaviours, and characteristics, which explores various personality theories and assessment methods.

- Political Psychology: The study of the psychological factors influencing political beliefs, behaviours, and decision-making, which examines political attitudes and voting behaviour.

- Positive Psychology: The study of the situations and experiences that promote human strengths, well-being, and happiness, which researches resilience and well-being interventions.

- Psycholinguistics: The study of the development and mechanics of learning and producing language.

- Psychometrics: The development of psychological tests and measurement tools, which ensure that assessments are reliable and valid.

- Rehabilitation Psychology: The application of psychological principles and research evidence to support individuals with disabilities or chronic health conditions, which help them to adapt and improve their quality of life.

- Religious Psychology: The study of the impact of religion and spirituality on mental health and well-being, which explores faith, and religious identity and practices.

- School (Educational) Psychology: The application of psychological principles and research evidence to support students’ mental health, academic success, and well-being within educational settings, which focuses on interventions for academic and behavioural challenges.

- Sensation and Perception Psychology: The study of how sensory organs receive and interpret environmental information, which focuses on vision, hearing, and touch perception.

- Social Psychology: The study of how social interactions and group dynamics influence individual behaviour and attitudes, which explores topics like prejudice, conformity, and social influence.

- Space Psychology: The study of how astronauts and cosmonauts are psychologically affected by long-duration missions in space travel and environments. This discipline examines factors like isolation, confinement, microgravity, risk, and the effects of a unique and challenging environment on mental health, behaviour, and cognitive functioning.

- Sport and Exercise Psychology: The application of psychological and research evidence to support athletes and individuals to enhance performance, motivation, and well-being in sports and physical activity.

- Traffic Psychology: The study of drivers’ behaviours and road safety, which works on interventions to promote safe driving and reduce traffic-related accidents.

In summary, this list of sub-disciplines of psychology offers us a glimpse into the many ways to explore psychology. Whether it’s in examination of individual behaviours, societal influences, biological underpinnings, or the unique challenges of specific environments, each area contributes valuable insights. Together, they form a cohesive understanding that helps us appreciate the complexity of the human mind and behaviour in various contexts.

Moving from the exploration of psychology’s subdisciplines, we now turn our attention to the professional associations that play a crucial role in defining and shaping the field. These organisations are instrumental in advancing psychological research, practice, and education, ensuring the discipline’s integrity and evolution within Canada and beyond.

Professional Associations in Psychology

This overview provides a brief look into the organisations that shape and define the field of psychology in Canada, highlighting their roles, missions, and contributions to the discipline. Each organisation plays a pivotal role in the development and application of psychological knowledge and practice, both within Canada and on a global stage.

The Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) was established as the premier organisation for psychologists in Canada, mirroring the role of the American Psychological Association (APA) in the United States, with a distinct focus on the Canadian context. The CPA’s primary mission is to foster the advancement of psychology as a science, as a profession, and as a means of promoting health and human welfare (Canadian Psychological Association, 2020).

The CPA comprises various sections, paralleling the divisions within the APA, each dedicated to a specific area of psychological study and practice. The CPA’s membership is diverse, encompassing individuals at various stages of their psychology careers, from students to doctoral-level professionals. These members contribute to a range of sectors such as education, healthcare, government, and private practice, highlighting the wide-reaching impact of psychology in society (Canadian Psychological Association, 2020).

The American Psychological Association (APA), established in 1892, is a leading professional organisation for psychologists in the United States and has significant influence in Canada and other countries. It plays a crucial role in setting ethical standards, advocating for the profession, and disseminating psychological knowledge through its comprehensive publishing program, including the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. This manual outlines the APA citation style, a cornerstone of scholarly writing in psychology and many related disciplines. The APA’s efforts extend beyond publication, encompassing the development of educational standards, public outreach, and policy advocacy to advance the field and promote mental health and well-being globally.

A parallel organisation, the Association for Psychological Science (APS), founded in 1988, aims to promote a scientific approach to psychology. Emerging from a divergence in focus within the APA, the APS emphasises research and education in psychology, publishing five notable research journals and actively engaging in advocacy (Association for Psychological Science, 2020). While its membership is predominantly based in the United States, it has a significant international presence.

Additionally, various organisations, including the National Latina/o Psychological Association (NLPA), the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA), the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (SIP), provide valuable networking and collaboration opportunities for psychologists from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds. These groups are instrumental in addressing psychological and social issues that may be overlooked in mainstream discussion of psychology (NLPA, 2020; AAPA, 2020; ABPsi, 2020; SIP, 2020).

The Registered Psychological Association (RPA) serves a critical function in the field of psychology, primarily focusing on the regulation and standardisation of professional practice. Its core purpose is to maintain high standards of competence and ethical behaviour among practicing psychologists. The RPA achieves this by setting rigorous criteria for registration and licensure, ensuring that only qualified individuals are permitted to practice psychology. This registration process typically involves verifying educational credentials, assessing professional training, and sometimes requiring the passing of a licensing examination. Furthermore, the RPA provides ongoing professional development opportunities and resources to its members, fostering a commitment to lifelong learning and advancement in the field. By upholding these standards, the RPA plays a vital role in protecting the public by ensuring that psychological services are provided by competent and ethical professionals (Registered Psychological Association, 2020).

In summary, the field of psychology in Canada is shaped and supervised by various organisations, each contributing uniquely to the discipline. These organisations collectively ensure the growth, integrity, and application of psychological knowledge. Their efforts not only enhance the field of psychology but also ensure that the services provided to the public are of the highest standard, reflecting the evolving needs and diversity of Canadian society.

Careers in Psychology

Psychologists can work in many different places doing many different things. In general, anyone wishing to continue a career in psychology at a 4-year institution of higher education will have to earn a doctoral degree in psychology for some specialties and at least a master’s degree for others. In most areas of psychology, this means earning a Ph.D. in a relevant area of psychology. “Ph.D.”refers to a doctor of philosophy degree, but here, philosophy does not refer to the field of philosophy per se. Rather, philosophy in this context refers to many different disciplinary perspectives that would be housed in a traditional college of liberal arts and sciences.

Why a Doctorate in Philosophy is Not Necessarily about Philosophy

The Ph.D. designation traces its origins back to the medieval European universities where the term “philosophy” did not refer solely to the study of philosophical thought as it is often understood today. Instead, “philosophy” was used in a broader sense, meaning the “love of wisdom”. It encompassed all areas of scholarly pursuit and was considered the foundation of all knowledge. This historical context helps explain why the term “Doctor of Philosophy” is applied to doctoral degrees in many disciplines, including psychology (Verger, 1999).

The requirements to earn a Ph.D. vary from country to country and even from school to school, but usually, individuals earning this degree must complete a dissertation. A dissertation is essentially a research paper or bundled published articles describing research that was conducted as a part of the candidate’s doctoral training. In Canada, a dissertation generally has to be defended before a committee of expert reviewers before the degree is conferred.

Once someone earns a Ph.D., they may seek a faculty appointment at a university or college. Being on the faculty of a university or college often involves dividing time between teaching, research, and service to the institution and profession. The amount of time spent on each of these primary responsibilities varies dramatically from school to school, and it is not uncommon for faculty to move from place to place in search of the best personal fit among various academic environments.

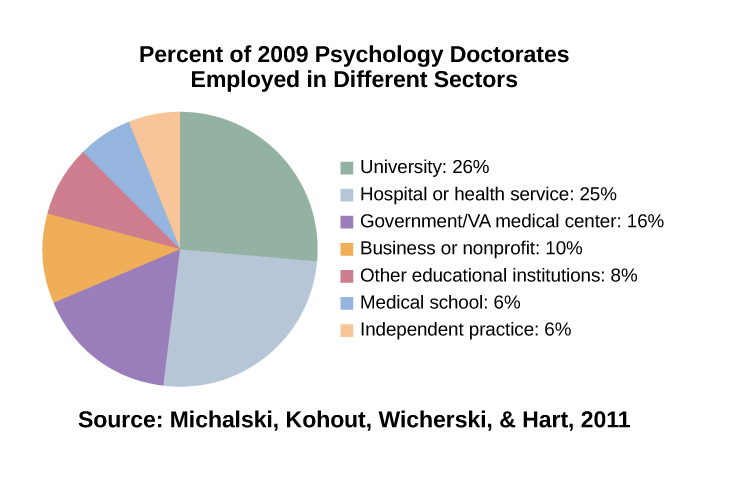

Figure IP.2 shows the proportion (percent) of people with Ph.D.s employed in various work environments.

Other Careers in Academic Settings

Oftentimes, schools offer more courses in psychology than their full-time faculty can teach. In these cases, it is not uncommon to bring in an adjunct faculty member or instructor. Adjunct faculty members and instructors usually have an advanced degree in psychology, but they often have primary careers outside of academia and serve in this role as a secondary job. Alternatively, they may not hold the doctoral degree required by most 4-year institutions and use these opportunities to gain experience in teaching.

Some people earning Ph.D.s prefer to research in an academic setting and may not be interested in teaching. These individuals might take on faculty positions that are exclusively devoted to conducting research. This type of position would be more likely an option at large, research-focused universities.

In some areas in psychology, it is common for individuals who have recently earned their Ph.D. to seek out positions in postdoctoral training programs that are available before going on to serve as faculty. In most cases, scientists in training will complete one or two postdoctoral programs before applying for a full-time faculty position. Postdoctoral training programs allow young scientists to further develop their research programs and broaden their research skills under the supervision of other professionals in the field.

Career Options Outside of Academic Settings

Individuals who wish to become practicing clinical psychologists have another option for earning a doctoral degree, which is known as a Psy.D.. Psy.D. programs generally place less emphasis on research-oriented skills and focus more on application of psychological principles in the clinical context (Norcorss & Castle, 2002).

Regardless of whether they are earning a Ph.D. or Psy.D., in most provinces, an individual wishing to practice as a licensed clinical or counselling psychologist may complete postdoctoral work under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. After an individual has met the provincial requirements, their credentials are evaluated to determine whether they can sit for the licensure exam. Only individuals that pass this exam can call themselves licensed clinical or counselling psychologists (Norcross, n.d.). Licensed clinical or counselling psychologists can then work in a number of settings, ranging from private clinical practice to hospital settings. It should be noted that clinical psychologists and psychiatrists do different things and receive different types of education. While both can conduct therapy and counselling, clinical psychologists have a Ph.D. or a Psy.D., whereas psychiatrists have a doctor of medicine degree (MD). Licensed clinical psychologists can administer and interpret psychological tests. Psychiatrists can prescribe medications.

Individuals earning a Ph.D. can work in a variety of settings, depending on their areas of specialisation. For example, someone trained as a biopsychologist might work in a pharmaceutical company to help test the efficacy of a new drug. Someone with a clinical background might become a forensic psychologist and work within the legal system to make recommendations during criminal trials and parole hearings, or serve as an expert in a court case.

While earning a doctoral degree in psychology is a lengthy process, usually taking between 5–6 years of graduate study (DeAngelis, 2010), there are a number of careers that can be attained with a master’s degree in psychology. People who wish to provide psychotherapy can become licensed to serve as various types of professional counsellors (Hoffman, 2012). Relevant master’s degrees are also sufficient for individuals seeking careers as school psychologists (National Association of School Psychologists, n.d.), in some capacities related to sport psychology (American Psychological Association, 2014), or as consultants in various industrial settings (Landers, 2011, June 14). Undergraduate coursework in psychology may be applicable to other careers such as psychiatric social work or psychiatric nursing, where assessments and therapy may be a part of the job.

As mentioned in the opening section of this chapter, an undergraduate education in psychology is associated with a knowledge base and skill set that many employers find desirable. It should come as no surprise, then, that individuals earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology find themselves in a number of different careers, as shown in Table IP.1. Examples of a few such careers can involve serving as case managers, working in sales, working in human resource departments, and teaching in high schools. The rapidly growing realm of healthcare professions is another field in which an education in psychology is helpful and sometimes required. For example, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) exam that people must take to be admitted to medical school now includes a section on the psychological foundations of behaviour.

| Ranking | Occupation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Mid- and top-level management (executive, administrator) |

| 2 | Sales |

| 3 | Social work |

| 4 | Other management positions |

| 5 | Human resources (personnel, training) |

| 6 | Other administrative positions |

| 7 | Insurance, real estate, business |

| 8 | Marketing and sales |

| 9 | Healthcare (nurse, pharmacist, therapist) |

| 10 | Finance (accountant, auditor) |

Table IP.1 Adapted from Fogg, Harrington, Harrington, & Shatkin (2012).

Watch this video: The Truth about Getting a Psychology Degree (7 minutes)

“The Truth about Getting a Psychology Degree” video by Phil’s Guide to Psy.D. is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Watch this video: 10 Psychology Careers To Know About (6.5 minutes)

“10 Psychology Careers To Know About” video by Psych2Go is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Psychology is an Imperfect Science with Some Problematic Words

Psychological science, like any field of study, is not perfect. One significant challenge we face in psychology involves our terminology. Some terms, despite being scientifically debatable or ethically problematic, have become deeply ingrained in both our scientific and everyday language. In this textbook, we will discuss many issues important to human psychology. Occasionally, we’re compelled to use terms that, despite being scientifically discredited as inaccurate or harmful, persist in our discussions. Yet, these words have become inextricably woven into how we define ourselves and talk about our social relationships; these words are “dead things walking” like ghosts, or remnants of past understandings that continue in our vocabulary. Since we have no words — yet — to substitute for these terms, we still need to use them. When using these problematic words, however, we must always remember that these terms have dubious, unethical, or unscientific origins.

Some Problematic Words Used in Psychology

Race

Scientifically, the human species does not possess enough genetic variation to justify the categorisation into distinct races (Sussman, 2014). Yet, the social construct of race, rooted in historical inaccuracies and prejudices, has led to significant social and psychological consequences. The legacy of race, intertwined with false narratives, racial discrimination, and eugenic and anti-BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) violence, has perpetuated unequal access to resources and opportunities. This impacts the lived experiences of racialized individuals in profound ways. While there is no genetic basis for human race, racial identity and race-based prejudice, race-biased systems are very real and require that we continue to use the term “race” in our scientific and social conversations. We have to understand that “race” in psychology does not refer to the genetic meaning of race.

“Heterosexual” and “homosexual”

The terms “heterosexual” and “homosexual” were first introduced in the late 19th century by a pseudonymous author likely to be Daniel von Kászony (Janssen, 2021). These terms were initially used to classify individuals based on their sexual preferences, often with moral judgments attached, categorising people into “good” or “bad” based on their sexual orientation. This binary classification system has been criticised for its oversimplification of human sexuality and its contribution to the stigmatisation of non-heteronormative (not strictly heterosexual) sexual orientations.

Furthermore, the term “straight,” used in everyday language to denote heterosexuality, implies a normative or “correct” sexual orientation, thus marginalising and invalidating other forms of sexual identity and expression. Such terminology reflects the political and unethical origins of these concepts, which continue to influence societal attitudes and biases. Even though terms like homosexual, heterosexual and straight are problematic, they are frequently used in scientific and everyday discussions.

As psychologists, it is crucial to acknowledge the impact of these and other problematic terms. Clearly we also need to develop more scientifically accurate terminology. It is essential to critically examine the origins, implications, and ethical considerations of the language we use. By doing so, we can work towards a more inclusive and respectful discourse that acknowledges the diversity of human experiences and identities. Being mindful of the origins of the terms we use is a step towards ending systemic biases and injustices.

Section Summary

In this section we focus on the diverse subdisciplines within psychology, offering insights into the broad range of topics available for study. We showcase some of psychology’s breadth and diversity. We continue with a discussion of the roles of professional associations and the variety of career paths within psychology. We learn about the contributions of organisations like the Canadian Psychological Association to the advancement of the discipline and outline the myriad career opportunities available to psychology graduates, spanning from academic research to clinical practice and beyond.

We conclude by acknowledging that psychology, like any science, has its flaws, especially in its use of language. Terms considered scientifically inaccurate or ethically questionable, such as race, homosexual, heterosexual, and straight are still used in both academic and everyday contexts. These terms, lacking a solid scientific basis and promoting oversimplified views, are rooted in historical inaccuracies and prejudices, leading to discrimination and systemic biases. Psychologists must critically evaluate and update their terminology to more accurately reflect human diversity – without prejudice – and promote an inclusive and ethical practice. Despite the current lack of substitutes for these terms, we must use them while simultaneously remaining aware of their problematic origins.

Image Attributions

Figure IP.2. Figure IP.19 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).