Chapter 16. Gender and Sexuality

Development of Our Sexuality

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 25 minutes

While sex and sexuality are often linked to late adolescence/early adulthood, this section explores sexuality throughout the entire lifespan. Elements of sexuality are present at all ages, from newborns to elders. Although the context varies based on age and experience, there are considerable domains to explore. These include sensual experiences, genital awareness, maturation, and individual and/or partnered sexual interactions. We will use a biopsychosocial approach, incorporating aspects of psychodynamic theory. Our exploration will cover elements of sex and sexuality that may occur throughout one’s lifetime. Sexual education is commonly taught in middle or high school, except in abstinence-only programs. But could open discussions about sex and lifelong learning about relationships and sexual satisfaction be beneficial to everyone?

Let’s examine the research evidence around sexual development across the lifespan. Historically, there was a belief that children were either innocent or incapable of sexual feelings. However, research shows that physical signs of sexual arousal are present from birth. It’s important to remember that these early signs of sexuality in children are purely physical responses, not connected to adult concepts of sexuality like love or lust.

Early Childhood Sexual Development

Historically, children were seen as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). The physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth, however it would be inappropriate to associate adult meanings of sexuality, like seduction, power, love, or lust, with these early expressions. Childhood sexuality begins as a response to physical states and sensation. It is not similar to adult sexuality in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Infancy

Babies can experience erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can indicate overall physical contentment. It often accompanies feeding or warmth. Infants begin to explore their bodies as soon as they develop sufficient motor skills. They touch their genitals for comfort or to relieve tension, not to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood

Self-stimulation is common in early childhood. Curiosity about the body and others’ bodies is natural at this stage. As children grow, they often show their genitals to siblings or peers. They also may undress and touch each other (Okami, Olmstead, & Abramson, 1997). Toddlers (ages 1–3 years) explore their world and learn to control their actions.

During preschool years, children’s awareness of their bodies increases. This can lead to individual and peer-to-peer sexual play. Physical exploration games are common among young children. Between 50 to 85 percent of children engage in games that involve fantasy sexual play, exposure, or stimulation of genitals (O’Donovan, 2010). The way adult caregivers respond to this play has a formative role in later, mature sexual experiences. As we move from the early years of childhood into the middle childhood phase, the nature and understanding of sexuality continue to evolve.

Middle Childhood Sexual Development

Children this age may not have the curiosity of earlier years. Yet, they also may not have entered puberty. Regardless of sexual orientation, people reported an average age of their first sexual attraction around 10 years old (Lehmiller, 2018). This suggests that more factors impact school-aged children than early theories suggested.

In middle childhood, some school-aged children receive their first educational information about changing bodies, puberty, and reproduction. For trans youth, this time can be challenging. They may have concerns about physical changes at the onset of puberty. Early messages about bodies, sex, and sexuality affect later attitudes and behaviour. Comprehensive sex education before young people become sexually active can delay the onset of sexual activity. It also increases sexual well-being (O’Donovan, 2010). Additionally, support for trans youth in terms of health options is critical for their physical and mental health outcomes (Turban, King, Carswell, & Keuroghlian, 2020). Moving on from middle childhood, we next explore the complexities and significant changes of adolescent sexual development.

Adolescent Sexual Development

The adolescent growth spurt is typically followed by the process of sexual maturation. Sexual changes fall into two categories: primary and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For some, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and the first menstrual period. For others, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and the first ejaculation of semen. This occurs around 9-14 years old (Breehl & Caban, 2020). The timing of puberty has significant social implications. It impacts self-esteem, and this interaction is context-dependent. While typical adolescent development follows a certain trajectory, it’s important to consider variations such as precocious and delayed puberty and their implications.

Anatomical Sexual Differentiation

Humans come in a variety of shades, sizes and proportions, yet in total, our bodies are more similar to each other than they are different. In fact the human body shares similarities with bodies across the diversity of life.

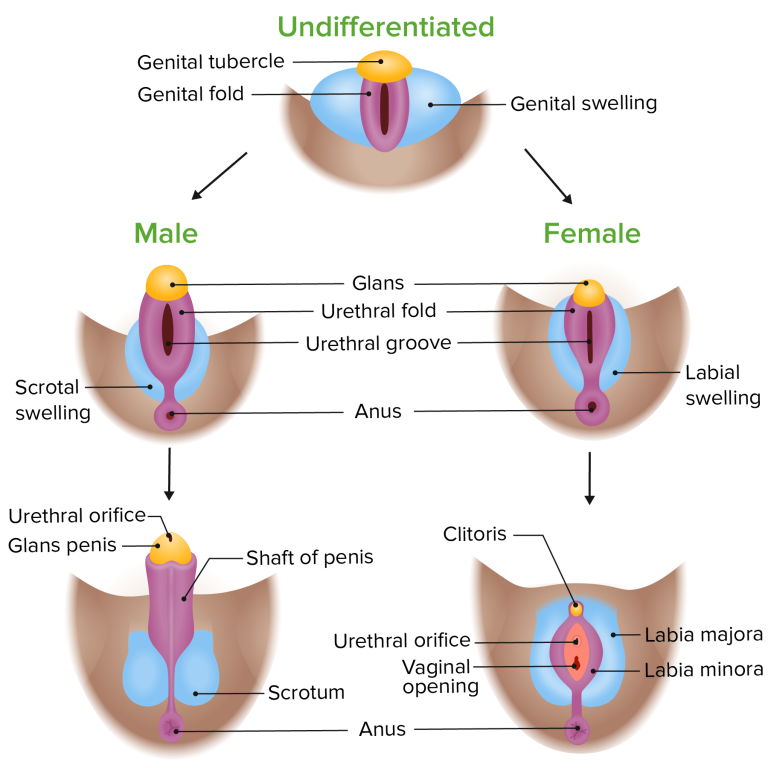

Sex differentiation, also referred to as sexual differentiation, is the process in which genitals and reproductive organs develop within the womb as a result of complex hormonal processes altering neutral tissues to develop along female and male lines and in which varying combinations are possible as well. Secondary sex characteristics begin to develop further as part of the sex differentiation process during puberty. Therefore, prenatal development, as well as changes that further occur during puberty, create a cascade of events that results in physical changes to the body. Chromosomes, genes, gonads, hormones, and hormone receptor sites play key roles within the endocrine system that influences sex development. Sex is both a genetic and environmental experience in which epigenetic factors can alter the way that genes function, resulting in changes to hormone production and hormone receptor sites at different points across the lifespan.

Prenatal

Chromosomes and genetic sex

The first step in differentiation of the reproductive organs happens with a sexless collection of cells at an area called the germinal ridge. In mammals, the main determinant of the pathway the germinal ridge follows is the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. This gene leads to the growth and specialisation of cells in the inner portion of the germinal ridge, which eventually become the testes. In the absence of this gene, the outer part of the germinal ridge develops into ovaries. Both the testes and ovaries are gonads — reproductive organs that contain reproductive hormones and gametes (sperm or eggs). In most XY individuals, high levels of fetal androgens, like testosterone, released from the testes promote development of the external genitals into a penis. In the absence of testosterone, this same tissue becomes a vagina. You cannot always tell the genetic sex of a newborn by observing their external genitalia, however. The practice of sexing newborn infants by visual inspection of genitals historically led to some misclassification of intersex people. The terms assigned female at birth (AFAB) and assigned male at birth (AMAB) are used to describe biological sex more accurately than the terms female and male. AFAB and AMAB is more evidence-based language because it acknowledges that the person making the first sex assignment does not have all the facts about the biological sex of the infant. This AFAB and AMAB terminology is preferred by many members of transgender, intersex and non-binary communities since it acknowledges an individual may be intersex but have external genitals that “look female” or “look male”.

Commonalities between female, intersex, and male reproductive anatomy

During embryonic development the female and male fetus are indistinguishable before about 10 weeks of pregnancy. Fetal tissues begin in an undifferentiated state, and based on genetic signals and the intrauterine environment the reproductive organs usually differentiate into structures typical of females and males. This means that for most of the reproductive parts there is an analogous part in the other sex that arose from the same original tissues. For example, testes and ovaries develop from the same tissue, originally located in the abdomen. Testes typically move down and outside the abdomen as they develop; ovaries remain internal. Some structures (such as the oviducts) have a structure that was common in early development, but completely or partially disappears in later development; other structures (such as the uterus) have analogues that are very subtle structures what’s typically called the male anatomy. See Table GS.4 (below) for a list of analogous structures in female, intersex and male anatomy.

| Female | Intersex | Male |

|---|---|---|

| clitoral head | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | glans (head of the penis) |

| v-shaped internal structure of the clitoris | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | penis shaft |

| clitoral hood | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | foreskin |

| labia minor | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | penis skin |

| ovary | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | testicle |

| labia majora | Could look more like female or more like male anatomy or be somewhere in-between. Intersex anatomy can vary. | scrotum |

Secondary Sexual Characteristics

| Female | Intersex | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Deposition of fat, predominantly in breasts and hips | Varies widely due to the diverse nature of intersex conditions, including combinations of characteristics typically associated with female and male bodies | Increased larynx size and deepening of the voice |

| Breast development | Influenced by individual hormonal levels, which might differ from typical female or male hormonal profiles | Increased muscular development |

| Broadening of the pelvis and growth of axillary, pubic and body hair | Varies widely due to the diverse nature of intersex conditions, including combinations of characteristics typically associated with female and male bodies. May undergo medical or surgical interventions to alter characteristics; experiences and identities are diverse, reflecting a wide range of expressions | Growth of facial, axillary, and pubic hair, and increased growth of body hair |

Something to keep in mind as well is that people can experience varying degrees of muscular, breast and hair development depending upon their genetic and environmental makeup. For instance, some youth at the beginning of puberty may see breast tissue growth as well as other body fat increases, and others may have facial and body hair growth. One example in this complex process is how unused endogenous (naturally occurring) testosterone is converted to estrogen, for instance, making it not about how much testosterone is present and rather how that testosterone is being used or unused in the body. Also, hormone receptor sites in female cells are often more reactive to lower levels of testosterone. Intersex individuals, females and males all have estrogen and testosterone influencing the changing body during puberty. It is incorrect to view testosterone as a strictly “male” hormone and estrogen as a strictly “female” hormone.

As a child with XX chromosomes reaches puberty, typically the first visible change is the development of the breast tissue. This is followed by the growth of axillary (e.g., armpit and leg) and pubic hair. A growth spurt normally starts at approximately age 9 to 11, and may last two years or more. During this time, their height can increase 3 inches a year. The next step in puberty is menarche, the start of menstruation.

For some, the growth of the testes is typically the first physical sign of the beginning of puberty, which is followed by growth and pigmentation of the scrotum and growth of the penis. The next step is the growth of hair, including armpit, pubic, chest and facial hair. Testosterone stimulates the growth of the larynx and thickening and lengthening of the vocal folds, which causes the voice to drop in pitch. The first fertile ejaculations typically appear at approximately 15 years of age, but this age can vary widely across individuals. Unlike the early growth spurt observed in females, the male growth spurt occurs toward the end of puberty, at approximately age 11 to 13, and a child with XY chromosomes can increase in height as much as 4 inches a year. In for some adolescents with XY chromosomes, pubertal development can continue through the early 20s.

How can Hormone Blockers Help Prevent Harm?

Hormone blockers for transgender children and youth is a medical strategy aimed at pausing puberty. This pause is important as it prevents the emergence of unwanted, permanent, and gender-incongruent secondary sex characteristics that can lead to significant dysphoria and mental health challenges for transgender individuals. There are many opinions regarding the administration of hormone blockers. Concerns are often raised about the decision-making capabilities of young individuals and the extent to which parental consent should play a role.

Notwithstanding these debates, scientific evidence shows hormone blockers are a vital intervention for supporting transgender children and youth. These treatments offer a crucial respite/time out, permitting individuals to navigate their gender identity without the compounding stress of undesired physical changes. Studies consistently show that hormone blockers can lead to markedly better mental health outcomes and a reduced risk of self-harm among transgender youth (Chen et al., 2021; Eisenberg et al., 2022; Turban et al., 2020). Furthermore, evidence suggests that early support and gender-affirming care, including the use of hormone blockers, are associated with lower rates of depression and suicidal thoughts. Medical professionals and transgender health advocates highlight that transgender identities often become evident in early childhood and are enduring. They contend that the advantages of hormone blockers, notably in affirming a young person’s gender identity and lowering mental health risks, significantly outweigh the concerns.

In summary, while discussions around hormone blockers are complex, the evidence strongly advocates for their role in enhancing the well-being of transgender children and youth, emphasising the necessity for informed, compassionate, and supportive healthcare practices.

Watch this video: Human Physiology – Reproduction: Sex Determination and Differentiation (3 minutes)

“Human Physiology – Reproduction: Sex Determination and Differentiation” video by Janux is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Intersex Anatomy

About 1 in 1,000-1,500 people will be born noticeably intersex, with partial evidence of both a penis and vulva. Other intersex conditions, however, may not show up until later, e.g., during puberty or when trying to conceive children, making this number higher. Some estimates show that some intersex conditions can be as high as 1 in 59. The prevalence of intersex conditions, including those not immediately apparent at birth, can be as high as 1.7% of the population when considering a broader definition that includes all variations at the chromosomal, gonadal, hormonal, or genital level (Saulnier, Gallois, & Joly, 2021).

The term intersex is an umbrella term that encompasses many different variations to sex. Some intersex individuals have variations in their sex chromosomes. In some instances, a male can have XX chromosomes and a female can have XY chromosomes. Other variations are possible as well (X0, XXY, XYY, XXX). According to Dr. Charmian Quigley with the Intersex Society of North America (2008a), “The last time I counted, there were at least 30 genes that have been found to have important roles in the development of sex in humans. Of these 30 or so genes 3 are located on the X chromosome, 1 on the Y chromosome and the rest are on other chromosomes, called autosomes…In light of this, sex should be considered not a product of our chromosomes, but rather, a product of our total genetic makeup, and of the functions of these genes during development.” (para. 11-12) Therefore, we need to be conscientious when we oversimplify this process and relate sex to XX or XY chromosomes only and remember there is far more to the genetics of sexual development.

How Common or Rare is Intersex?

Just how rare or common is an incidence rate of 1.7% for intersex conditions? While this 1.7% rate is relatively uncommon, it is not exceedingly rare, indicating that out of every 59 individuals, one is likely to be intersex. Table GS.6 aims to place the incidence of intersex conditions in context by comparing it to other human traits and conditions, ranging from the rare ability of perfect pitch (0.01% of the population) to the more common trait of left-handedness (10%). This comparison reveals that being intersex is as prevalent as having green eyes or ambidexterity and is more common than having red hair or female colour blindness.

| Trait | Description | Incidence Rate | Percent of Population | Disclaimers or Exceptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Pitch | Ability to identify musical notes without reference | 1 in 10,000 | 0.01 | |

| Ambiguous genitals at birth | Newborns who have genitalia that do not allow doctors to easily assign them as female or male | 1 in 1,500 to 2,000 | 0.05-0.07 | |

| Identical Twins | Twins from the same egg, identical genetically | 1 in 250 | 0.4 | |

| Red Hair | Rare hair colour, most common in people of Northern European descent | 1 in 200 | 0.5 | World wide; greater incidence in places like Scotland |

| Colour Blindness (Females) | Difficulty distinguishing colours, less common in females | 1 in 200 | 0.5 | X-linked recessive trait |

| Ambidexterity | Ability to use both hands equally well | 1 in 100 | 1 | |

| Green Eyes | Rare eye colour, more common in women | 1 in 100 | 1 | |

| Peanut allergy | Body’s immune system mistakenly identifies peanuts as harmful | 1 in 71 | 1.4 | Sicherer, et al., 2010 |

| Intersex (All genital ambiguities, and chromosomal, hormonal, and other anatomical variations) | Individuals born with reproductive or sexual chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy that goes beyond strict medical definitions for female or male anatomy or genetics | 1 in 59 | 1.7 | Saulnier et al. (2021) |

| Fraternal Twins | Twins from separate eggs, genetically distinct | 1 in 42 | 2.38 | |

| Colour Blindness (Males) | Difficulty distinguishing colours, more common in males | 1 in 12 | 8 | X-linked recessive trait |

| Left-Handedness | Preference for using the left hand for tasks | 1 in 10 | 10 |

Watch this video: What It’s Like To Be Intersex (3.5 minutes)

“What It’s Like To Be Intersex” video by As/Is is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Image Attributions

Figure GS.5.Image by Lecturio as found in Introduction to Human Sexuality is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).