Chapter 17. Well-being

Stress and Health

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 51 minutes

Few would deny that today’s university students are under a lot of pressure. In addition to the usual stresses and strains inherent to the university experience, such as exams and term papers, students today face increased tuition, burdensome debt, and the prospect of difficulty finding employment after graduation. A significant population of university students may face additional stressors, such as raising children or holding down a full-time job while working toward a degree.

Life is filled with many additional challenges beyond those found in university or in the workplace. We might have concerns with financial security, difficulties with friends or neighbours, responsibilities to our family, and not enough time to do the things we want to do. Even minor hassles, such as losing things, traffic jams, and loss of internet service, involve pressure and demands that can make life seem like a struggle and compromise our sense of well-being.

In this section of the chapter, we start by defining stress, a complex phenomenon influenced by both external situations and our internal responses. Stress can stem from feeling overwhelmed by exams, deadlines, and societal pressures, impacting our mental and physical health. It can be viewed through two main lenses: as specific external triggers or as our physical and emotional reactions to these demands.

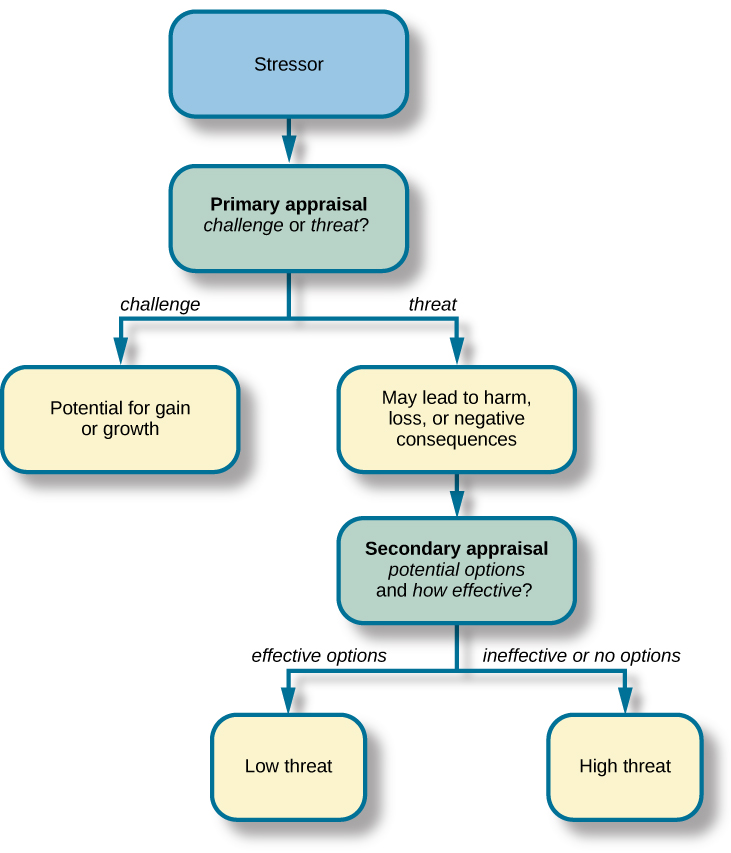

Next, we explore the Lazarus Appraisal Model of Stress, which emphasises individual appraisal in the experience of stress. This model introduces the concepts of primary and secondary appraisal, helping us understand how our interpretation of events influences our stress levels. Using a practical scenario of encountering a barking dog on a forest path, we delve deeper into the Lazarus model. This section illustrates how individual perceptions significantly influence stress responses, showing the subjective nature of stress.

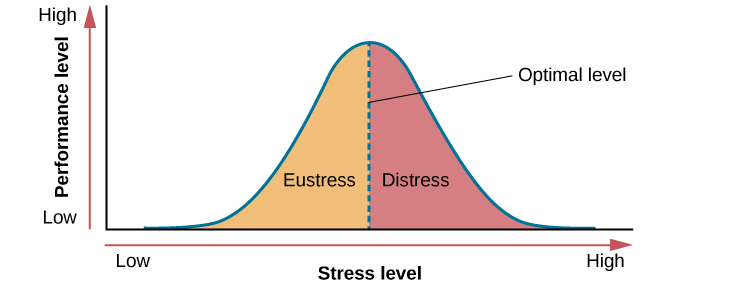

We then discuss the dual nature of stress, distinguishing between eustress (positive stress) and distress (negative stress). Understanding the difference helps us harness the motivating aspects of eustress while minimising the harmful effects of distress on our mental and physical health. This section explores the relationship between stress and performance, highlighting how moderate stress can enhance performance and well-being, but excessive stress can lead to burnout and decreased performance.

We examine common stressors and their effects on our daily lives, noting how stress can manifest physically and mentally, influencing behaviours and health outcomes. Health psychology focuses on understanding how stress and other psychological factors impact health. This section delves into how health psychologists study and address the connection between stress and illness, aiming to promote healthier behaviours and lifestyles.

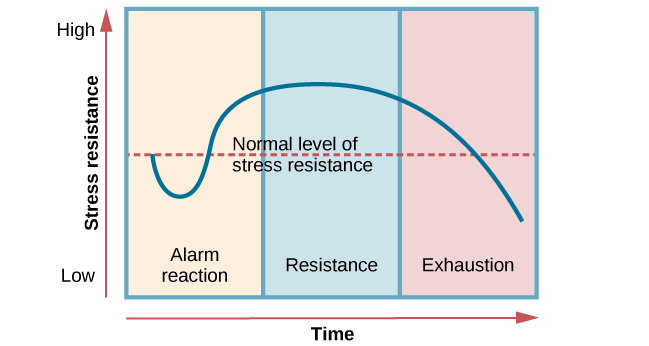

Walter Cannon’s fight-or-flight response theory is introduced, explaining how our bodies react to perceived threats with physiological changes that prepare us to confront or escape danger. We transition to Hans Selye’s concept of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), which examines the prolonged effects of stress on the body. This model outlines how our bodies cope with sustained stress through stages of alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

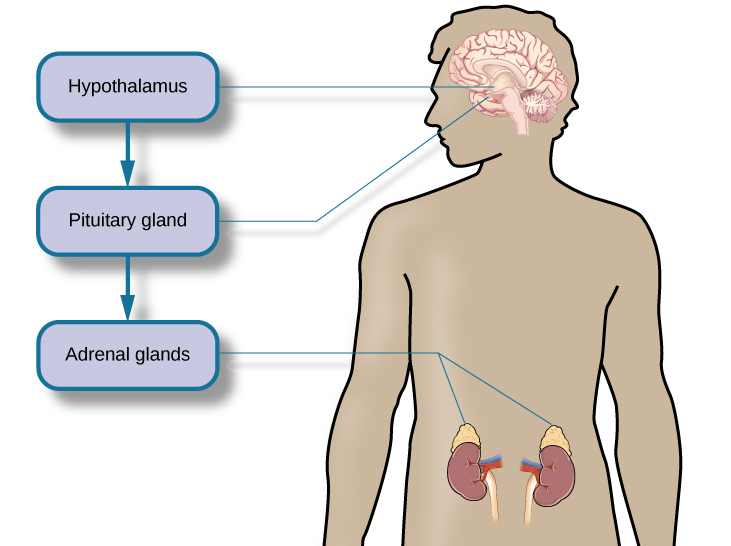

We learn the physiological mechanisms behind stress, focusing on the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. We explore how these systems respond to stress and the implications for our health. Life changes, whether positive or negative, can act as significant stressors. We discuss the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) developed by Holmes and Rahe, which quantifies the impact of life events on stress and health.

What is Stress?

Stress, a prevalent aspect of modern life, especially for university students grappling with academic pressures, financial burdens, and personal challenges, is a complex phenomenon influenced by both external situations and our internal responses. It encompasses a range of experiences from feeling overwhelmed by exams and deadlines to navigating societal pressures, all of which can significantly impact our mental and physical health. Broadly defined, stress can be viewed from two perspectives: specific external triggers or our physical and emotional reaction to these demands (Lyon, 2012), underscoring the intricate interplay between our environment and how we perceive and cope with challenges.

The term stress, as it relates to the human condition, first emerged in scientific literature in the 1930s, but it did not enter our everyday language until the 1970s (Lyon, 2012). Today, we often use the term loosely in describing a variety of unpleasant feeling states; for example, we often say we are stressed out when we feel frustrated, angry, conflicted, overwhelmed, or fatigued. Despite the widespread use of the term, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision.

Researchers have struggled to agree on an acceptable definition of stress. Broadly, there are two primary ways of conceptualising stress: (1) the stimulus-based definition and (2) the response-based definition. The stimulus-based definition views stress as a result of specific external events or situations, such as a high-stress job or long commutes, which act as stimuli, triggering stress reactions. However, this approach has been critiqued for not accounting for individual differences in perception and reaction to these stimuli. On the other hand, the response-based definition focuses on the physical and emotional responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations, like increased arousal. This perspective emphasises the physiological aspect of stress but can overlook the fact that such responses can also be triggered by positive or non-threatening events.

To better understand these definitions and their limitations, you can read Supplement WB.14 about of two students, Ti and Carli, who are about to leave their small town homes to move into a large university student residence.

Understanding the Lazarus Appraisal Model of Stress

The limitations of both the stimulus-based and response-based definitions lead us to consider a more comprehensive model of stress: the Lazarus Appraisal Model. Developed by Lazarus & Folkman in 1984, this model emphasises the role of individual appraisal in the experience of stress. It suggests that stress is not solely determined by external events or physiological responses but also by the ways an individual interprets and reacts to these events.

Primary and Secondary Appraisal

The process begins with what is known as primary appraisal, where an individual assesses the potential harm or threat a stressor might pose to their well-being. In the previous example of Ti and Carli (Supplement WB.14), the stressor was leaving home to move into university residence. The primary appraisal involves evaluating whether a situation or event is a threat, which could lead to harm, loss, or other negative consequences. Conversely, the same situation can be appraised as a challenge, presenting an opportunity for overcoming fear or demonstrating courage.

Secondary appraisal follows, where the individual assesses their ability to cope with the stressor, considering the resources they have at hand. This appraisal involves determining how effectively one can manage or adapt to the stressor. The perception of one’s ability to handle the situation influences whether it is viewed as a manageable challenge or a significant threat.

After exploring the stimulus-based and response-based definitions through the experiences of Ti and Carli, let’s delve deeper into the Lazarus appraisal model with a different scenario. This will help us further understand how individual perceptions significantly influence stress responses.

Facing Fido in the Forest: Another Walk Through the Lazarus Model

Let’s walk through the Lazarus model decision tree using the example of you hiking along a forest path when you suddenly encounter a large, loudly barking dog on a forest path. This model involves two key stages of appraisal: primary and secondary.

Primary appraisal

In the primary appraisal stage, you assess the situation to determine if the large, barking dog poses a threat to your well-being or if it represents a challenge.

- Perceived as a threat: If you perceive the dog as dangerous (due to its size, loud bark, and the isolated forest setting), you might appraise this situation as a threat. This perception could be based on past experiences, inherent fears of dogs, or the unexpected nature of the encounter. You anticipate potential harm or danger from the dog.

- Perceived as a challenge: Alternatively, you might perceive the encounter with the dog as a challenge. This could occur if you view the situation as an opportunity to overcome a fear of dogs or to demonstrate courage in handling unexpected situations. Your focus here is on the potential for personal growth or mastery in dealing with the situation.

Secondary appraisal

In the secondary appraisal stage, you evaluate your coping resources and options to handle the situation with the dog.

- Ineffective or no coping options available (perceived as a threat): If, on the other hand, you feel you lack the resources to deal with the dog (due to a lack of experience with dogs, absence of any means to protect yourself, or being alone in the forest), you might view the situation as a significant threat to your safety. This perception leads to a higher level of stress and potential feelings of helplessness or fear.

- Effective coping options available (perceived as a challenge): If you feel confident in your ability to handle the situation (perhaps due to previous positive experiences with dogs, knowledge about animal behaviour, or the presence of tools like a walking stick), you might view the encounter as a manageable challenge. You believe you have the necessary resources and strategies to safely navigate the situation.

Outcome based on appraisal

- High stress (threat perception with ineffective coping): If you appraise the dog as a threat and feel you cannot effectively cope with the situation, you are likely to experience a high level of stress. This stress could manifest as fear, anxiety, and physiological responses like increased heart rate or adrenaline rush.

- Low to moderate stress (challenge perception with effective coping): If you appraise the situation as a challenge and feel capable of handling it, your stress level may be lower or even positive in nature, characterised by a sense of alertness and readiness to act.

In summary, according to the Lazarus model, your experience of stress in encountering the barking dog on a forest path is determined not just by the presence of the dog (the external stimulus) but significantly by how you appraise the situation (threat or challenge) and your perceived ability to cope with it. This model underscores the subjective nature of stress and the importance of individual perception and evaluation in stress experiences.

Having navigated the Lazarus model with the example of the hiker and the barking dog, we can see how individual appraisal plays a crucial role in the experience of stress.

This understanding brings us back to Ti and Carli, whose experiences we can now re-examine through the lens of this model.

In summary, if a person appraises an event as harmful and believes that the demands imposed by the event exceed the available resources to manage or adapt to it, they will subjectively experience a state of stress. Conversely, if one does not appraise the same event as harmful or threatening, they are unlikely to experience stress. According to this definition, environmental events trigger stress reactions by the way they are interpreted and the meanings they are assigned. In short, stress is largely in the eye of the beholder: it’s not so much what happens to you as how you respond (Selye, 1976).

Stress: The Good and the Bad

Stress is often seen as something negative, but it can also be helpful. Stress can push us to do important things like study for exams, go to the doctor, exercise, and work hard. Selye, a scientist in 1974, said that stress isn’t always bad. He explained that stress can be a good thing that helps improve our lives. He called this good stress “eustress” (from a Greek word meaning “good”). Eustress is the kind of stress that makes you feel positive and can be good for your health and performance.

A moderate amount of stress can be beneficial in challenging situations. For example, athletes may be motivated and energised by pre-game stress, and students may experience similar beneficial stress before a major exam. Indeed, research shows that moderate stress can enhance both immediate and delayed recall of educational material. Male participants in one study who memorised a scientific text passage showed improved memory of the passage immediately after exposure to a mild stressor as well as one day following exposure to the stressor (Hupbach & Fieman, 2012).

But when stress exceeds this optimal level, it is no longer a positive force; it becomes excessive and debilitating, or what Selye termed distress (from the Latin dis = “bad”). People who reach this level of stress feel burned out; they are fatigued and exhausted, and their performance begins to decline. If the stress level remains excessive, health may begin to erode as well (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Stress and Performance

Figure WB.7 shows us that as stress increases, so does performance and well-being, up to a point. This is eustress. When stress reaches the best level (the highest point of a curve), performance is at its best. You feel fully energised and focused, and you work efficiently. But if stress goes beyond this best level, it becomes too much and harmful; this is distress. People with too much stress feel burned out and tired, and their performance drops. If the stress level stays too high, it can even harm health. For example, students who are very stressed about a test might find it hard to concentrate, which can affect their test scores.

A graph features a bell curve that has a line going through the middle labeled “Optimal level.” The curve is labelled “eustress” on the left side and “distress” on the right side. The x-axis is labeled “Stress level” and moves from low to high, and the y-axis is labeled “Performance level” and moves from low to high.” The graph shows that stress levels increase with performance levels and that once stress levels reach optimal level, they move from eustress to distress.

Stress in Our Lives

Stress is a common experience. We all deal with it in different ways. It can feel like a heavy load, like when you have to drive in a blizzard, wake up late for an important job interview, run out of money, or aren’t ready for a big test. Stress is an experience that can include symptoms like a faster heart rate, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, and difficulty concentrating or making decisions. We may react to stress in unhealthy ways by drinking alcohol, smoking, or engaging in other dubious behaviours we hope will reduce the stress. While stress can sometimes be good, it can also lead to health problems, contributing to illnesses and diseases. Stress can cause physical reactions like a fast heartbeat or headaches, make it hard to think or decide, and lead to behaviours like drinking or smoking.

Health Psychology and Stress

The scientific study of how stress and other psychological factors impact health is part of health psychology. Health psychology is a subfield of psychology that focuses on understanding the importance of psychological influences on health and illness, and how people respond when they become ill (Taylor, 1999). Health psychology emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, a time of increasing awareness of the role behavioural and lifestyle factors play in the development of illnesses and diseases (Straub, 2007). In addition to studying the connection between stress and illness, health psychologists investigate issues such as the reasons people make certain lifestyle choices, e.g., smoking or eating unhealthy food, despite knowing the potential adverse health implications of such behaviours.

Health psychologists also work on creating and testing ways to help people change unhealthy behaviours. A key part of their job is to figure out which groups of people are more likely to have health problems because of the way they think or act. For instance, they might study how stress affects different age groups, like young adults versus older adults. By understanding who gets more stressed and how it changes over time, health psychologists can identify which age group might be more at risk for health issues like high blood pressure or anxiety disorders.

Watch this video: The Upside of Stress (4.5 minutes)

“The Upside of Stress” video by BrainCraft is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Cannon and the Fight-or-Flight Response

Stress, a universal experience, has intrigued scientists for nearly a century. A key figure in this exploration is Walter Cannon, an American physiologist whose groundbreaking work in the early 20th century has significantly shaped our understanding of how the body reacts to stress. Cannon’s insights into the fight-or-flight response have provided a foundational understanding of the body’s physiological mechanisms when confronted with stress.

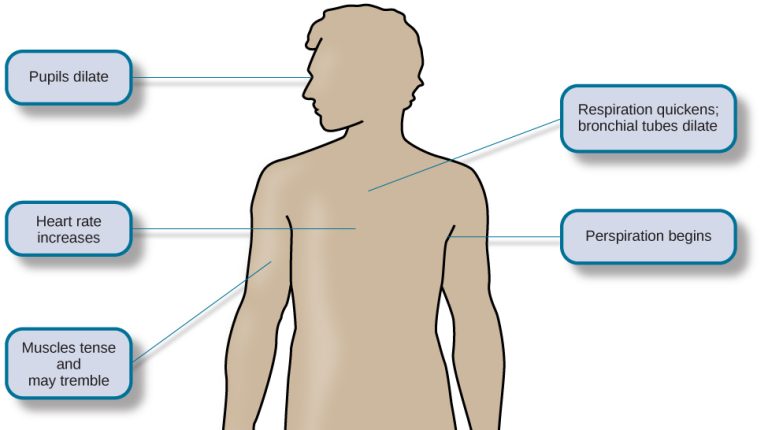

To illustrate Cannon’s fight-or-flight model, let’s return to our previous scenario, imagine you are back again, hiking in a forest when suddenly a large, barking dog appears. The dog, emerging from behind a stand of trees, stops about 50 yards from you. It notices you, barks louder, and starts moving in your direction. You think, “This is definitely not good,” and experience a series of physical reactions:

- Your pupils dilate.

- Your heart races and speeds up.

- You start breathing heavily and sweating.

- You feel butterflies in your stomach.

- Your muscles tense up, readying you to take action.

Cannon proposed that this reaction, termed the fight-or-flight response, occurs when a person experiences intense emotions, especially those associated with a perceived threat (Cannon, 1932). During the fight-or-flight response, the body is rapidly aroused by the activation of both the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system (Figure WB.10). This arousal prepares the person to either confront or escape the perceived threat.

In conclusion, Cannon’s concept of the fight-or-flight response has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of stress physiology. By identifying the body’s innate mechanism for maintaining homeostasis in the face of threats, Cannon’s work has laid the groundwork for further research into how we respond to stress. This response, crucial for survival, highlights the body’s remarkable ability to adapt to and manage challenging situations, a testament to the complex and dynamic nature of human physiology.

Having explored Cannon’s pivotal work on the immediate, fight-or-flight response to stress, we now turn to another seminal figure in stress research, Hans Selye. While Cannon focused on the body’s acute reaction to stress, Selye’s work delves into the prolonged effects of stress on the body. His concept of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) offers a broader perspective, examining how our bodies cope with sustained stress over time. This shift from the immediate to the enduring effects of stress marks a significant development in our understanding of how stress impacts us.

Selye and the General Adaptation Syndrome

Selye initially focused on sex hormones in rats, but he incidentally discovered that prolonged exposure to stressors — such as extreme cold, surgical injury, and excessive muscular exercise — led to adrenal enlargement, thymus and lymph node shrinkage, and stomach ulceration in the rats. Selye realised that these health issues were part of a set of body reactions that occur over time under stress, regardless of the stressor’s nature. He termed this the general adaptation syndrome, a universal response of the body to stress.

It is important to note that Selye’s experiments, while groundbreaking, involved methods that would not meet current ethical standards. The distress and harm inflicted on the rats in his labs raises significant ethical concerns. Additionally, the extrapolation of these findings to human populations should be approached with caution.

In summary, Selye’s general adaptation syndrome model illustrates how our bodies may respond to stress in stages: initially with a burst of energy, then adapting, and finally, potentially breaking down if the stress continues for too long.

Biological Basis of Stress

What happens inside our bodies when we experience stress? The physiological mechanisms are complex, involving two main systems: the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

When we perceive something as stressful, the sympathetic nervous system quickly triggers arousal. This includes releasing adrenaline from the adrenal glands, which activates our fight-or-flight responses, such as a faster heart rate and increased breathing. Simultaneously, the HPA axis, which operates more slowly, becomes active. The hypothalamus in the brain releases a hormone that prompts the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete various hormones, notably cortisol, which affects almost every organ and provides an energy boost in response to stressors.

In short bursts, this process can be beneficial, providing extra energy, temporarily improving immune function, and reducing pain sensitivity. However, prolonged or chronic stress, leading to extended cortisol release, can have detrimental effects. High cortisol levels can weaken the immune system and are often found in individuals with depression (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Geoffroy, Hertzman, Li, & Power, 2013).

These physiological reactions to stress prepare us for immediate action but can also increase the risk of illness. Extreme or chronic stress can have profound negative consequences. It contributes to psychological disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression and is linked to physical illnesses. For instance, people affected by the September 11 attacks showed higher rates of heart disease (Jordan, Miller-Archie, Cone, Morabia, & Stellman, 2011). Finnish food industry workers with self-reported stress symptoms were more likely to develop various disorders 11 years later (Salonen, Arola, Nygård, & Huhtala, 2008). South Korean employees with high work-related stress were more susceptible to the common cold (Park et al., 2011).

Having explored the immediate physiological responses to stress, we will now examine how these reactions can lead to physical illness and disease. In the following sections, we will delve into the mechanisms through which stress can lead to physical illness and disease.

Watch this video: Sympathetic Nervous System: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #14 (11 minutes)

“Sympathetic Nervous System: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #14” video by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Rat Park Experiments, Addiction and Environmental Stress

Watch this video: Addiction and the Rat Park Experiments – Short Version (1.5 minutes)

“Addiction and the Rat Park Experiments – Short Version” video by MinuteVideos Portfolio is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Life Changes as Stressors

Life changes, whether perceived as positive or negative, can act as significant stressors. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), developed by Holmes and Rahe in 1967, highlights how events like marriage, divorce, job loss, or moving to a new home require an individual to make substantial adjustments, thereby inducing stress. These life changes are assigned “life change units” (LCUs) to quantify their potential impact on a person’s health. Interestingly, the scale suggests that not only negative events but also positive ones, such as promotions or the birth of a child, can produce stress due to the changes they bring to one’s life.

| Life event | Life change units |

|---|---|

| Death of a close family member | 63 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 |

| Dismissal from work | 47 |

| Change in financial state | 38 |

| Change to different line of work | 36 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Beginning or ending school | 26 |

| Change in living conditions | 25 |

| Change in working hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | 20 |

| Change in schools | 20 |

| Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Minor violation of the law | 11 |

Table adapted from Holmes and Rahe (1967). The higher the number the more stressful the event.

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) provides researchers a simple, easy-to-administer way of assessing the amount of stress in people’s lives, and it has been used in hundreds of studies (Thoits, 2010). Despite its widespread use, the scale has been subject to criticism.

Understanding that life changes can be stressful regardless of their nature underscores the importance of developing coping mechanisms and support systems. It also highlights the subjective nature of stress, as individuals may perceive and react to the same event differently based on their personal resources, past experiences, and social support networks. Recognising and addressing the stress associated with life changes is crucial for maintaining mental health and well-being. This awareness can empower individuals to seek help when needed and to approach life’s transitions with strategies that promote resilience and adaptation.

Summary

This section delves into the complex nature of stress and its profound impact on health. It begins by defining stress. The section introduces the Lazarus Appraisal Model of Stress, providing a framework for understanding primary and secondary appraisal and how personal interpretation of stressors affects our stress response. We then discuss good stress (eustress) and bad stress (distress) discussing stress’ dual role in enhancing performance and contributing to health issues. Next we discuss the historical perspectives of Cannon’s fight-or-flight response and Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome which offer us insights into the body’s physiological responses to stress. The biological underpinnings of stress are explored, with a focus on the sympathetic nervous system’s role. Additionally, the Rat Park experiments are highlighted to discuss the relationship between environmental stress, addiction, and health. The section also considers the impact of significant life changes as stressors, utilising the Social Readjustment Rating Scale to illustrate how different events influence stress levels.

Reflecting on the above stress and health content, consider these questions: How can you reframe your perception of stressful events to transform them from threats into challenges that promote personal growth? What are some daily habits or activities you can adopt to counteract the negative effects of stress? What practical steps can you take to incorporate more eustress into your daily routine to enhance your well-being and performance?

Image Descriptions

Figure WB.6. Primary and secondary appraisal image description: A concept map showing the steps assessing a potential threat.

- Stressor

- Primary appraisal: Challenge or threat?

- If it’s a challenge, it’s a potential for gain or growth

- If it’s a threat, it may lead to harm, loss, or negative consequences

- Secondary appraisal: Potential options and how effective?

- If there are effective options, it is a low threat.

- If there are ineffective or no options, it is a high threat. [Return to Figure WB.6]

- Secondary appraisal: Potential options and how effective?

- Primary appraisal: Challenge or threat?

Image Attributions

Figure WB.6. Figure 14.3 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure WB.7. Figure 14.4 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure WB.8. Driving during a blizzard by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure WB.9. Flight-or-fight response by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure WB.10. Figure 14.8 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure WB.11. Figure 14.10 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure WB.12. Figure 14.11 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).