Chapter 17. Well-being

Stress and Illness

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 26 minutes

The stress response, a sophisticated and coordinated set of physiological reactions, is crucial for navigating potentially dangerous or threatening situations, such as the classic example of encountering a bear on a trail. This response prepares our body to face immediate challenges. However, when these physiological reactions are not just momentary but sustained over a prolonged period, they can have significant health implications. This is where the concept of biological embedding comes into play. Continuous exposure to stress, especially chronic or traumatic stress, can lead to lasting changes in our body’s systems. These changes are “embedded” biologically, altering our normal physiological responses. As a result, what is designed as a short-term survival mechanism can, over time, contribute to long-term health issues, reflecting the deep and enduring impact of prolonged stress on our physical and mental well-being.

Biological Embedding

Biological embedding is a concept used to describe how life experiences, particularly those involving stress or trauma, can have a lasting impact on biological systems and development. This process involves the way in which these experiences can lead to changes in the body’s physiological and biological systems, potentially affecting health across the lifespan.

In more technical terms, biological embedding occurs when experiences, especially in critical periods of development (like childhood or adolescence), alter the functioning of our biological systems in a way that persists over time. This can include changes in the endocrine system (which involves hormones), the immune system, and even at the genetic level through a process known as epigenetics, where the expression of genes is changed without altering the DNA sequence itself.

These changes can have long-term effects on an individual’s health, increasing the risk of various physical and mental health conditions. For example, exposure to chronic stress or trauma in early life can lead to a heightened stress response, which over time can contribute to a range of health issues, including cardiovascular disease, mental health disorders, and metabolic conditions.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences (AdverseCEs) are not just unfortunate incidents that occur in one’s childhood. Instead, they represent devastating events that can cast a long shadow over an individual’s life, shaping their future health and well-being. These events may include various forms of abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), neglect, or residing in a home where family members struggle with mental illness, substance addiction, divorce, the incarceration of a family member, or domestic violence (Felitti, et al., 2018). The more adversities one faces in childhood, the greater the risk of health issues later in life (Boles, 2021; Kwong & Hayes, 2017). For Indian Residential School (IRS) survivors and their descendants, these adversities are often compounded by the intergenerational transmission of trauma, cultural disconnection, and systemic inequities brought about by genocidal actions of European colonists. (McQuaid et al., 2017; Richmond et al., 2009; Gracey & King, 2009).

Allostasis and Allostatic Load

Allostasis is a term that describes how our body responds to stress by trying to maintain balance or stability. Think of it like a highly skilled juggler who keeps several balls in the air — the balls represent different stressors, and the juggler is your body trying to keep everything balanced. When faced with stress, our body activates several systems, including the brain, hormones, and immune system. This is similar to the juggler adding more balls to juggle when more tasks are thrown at them. Key players in this process are hormones like cortisol, epinephrine (also known as adrenaline), and norepinephrine. These hormones are like the juggler’s quick reflexes, helping the body adapt to new challenges by increasing heart rate, energy levels, and alertness.

However, if the stress continues for a long time or is very intense, it leads to what scientists call allostatic load. Imagine our juggler now having to juggle too many balls for too long. Eventually, the juggler gets tired, and it becomes harder to keep all the balls in the air. Similarly, allostatic load is the wear and tear that our body experiences when it’s constantly under stress. It’s like the body’s stress-response system getting overworked. This can happen when someone is repeatedly exposed to stressful situations, or if the stress is very intense, like the experiences of those in Indian Residential Schools. Over time, this constant stress can lead to health problems like high blood pressure, diabetes, and mental health issues. It’s as if the juggler’s muscles start to ache and they can’t perform as well anymore.

“Just Get Over It” is the Wrong Approach

Sometimes, it’s easy to wonder, “Why can’t survivors of trauma just get over it and leave the past behind?” The reality, deeply rooted in the principles of biological embedding and allostatic load, is far more complex. Traumatic experiences, particularly those in childhood, like those endured in Indian Residential Schools, don’t just impact the mind; they leave a lasting imprint on the body’s biological systems. This embedding alters hormonal balances, immune responses, and even gene expression, setting the stage for long-term health challenges. Additionally, the concept of allostatic load shows us how continuous or intense stress can overburden the body’s stress-response system, leading to a range of physical and mental health issues. These profound biological changes underscore the enduring nature of trauma, making it clear that “just getting over it” is not a simple matter of choice or willpower, but a complex process of healing and adaptation.

In summary, allostasis is our body’s way of trying to keep up with the demands of stress, like a skilled juggler. But when the stress is too much or goes on for too long, it leads to allostatic load, which is like the juggler getting worn out. This concept helps us understand why prolonged or intense stress can have such a significant impact on our health.

Watch this video: How Chronic Stress Harms Your Body (5.5 minutes)

“How Chronic Stress Harms Your Body” video by SciShow Psych is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Stress and the Immune System

In a sense, the immune system is the body’s surveillance system. It consists of a variety of structures, cells, and mechanisms that serve to protect the body from invading microorganisms that can harm or damage the body’s tissues and organs. When the immune system is working as it should, it keeps us healthy and disease free by eliminating harmful bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that have entered the body (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Watch this video: How Mental Stress is Killing Your Immunity – Effect of stress on the immune system (5 minutes)

“How Mental Stress is Killing Your Immunity – Effect of stress on the immune system” video by MEDSimplified is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Stressors and Immune Function

The question of whether stress and negative emotional states can influence immune function has been a focus of research for over three decades, leading to significant advancements in health psychology (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2009). Psychoneuroimmunology, a term first coined in 1981, studies the impact of psychological factors like stress on the immune system (Zacharie, 2009). This field has evolved from understanding the connection between the central nervous system and the immune system.

Classical conditioning studies, such as those by Ader and Cohen (1975, 2001), have shown that immune responses can be conditioned in both animals and humans. This suggests that psychological factors can influence immunity.

Recent research has continued to explore various stressors and their effects on the immune system. For example, workplace stress is significantly associated with lowered immune function, particularly in the production of antibodies (Smith et al., 2018). Prolonged exposure to stressors like marital discord and caregiving for Alzheimer’s patients can lead to a weakened immune response, particularly in older adults (Johnson et al., 2019).

The physiological connection between the brain and the immune system is well-established. The sympathetic nervous system’s innervation of immune organs and the impact of stress hormones on immune function, such as the inhibition of lymphocyte production, are key aspects of this connection (Maier et al., 1994; Everly & Lating, 2002).

Recent experimental studies have further confirmed the link between stress and impaired immune function. For example, individuals under chronic stress were more susceptible to viral infections like the common cold (Williams et al., 2020). Similarly, caregivers under chronic stress exhibited a poorer antibody response to influenza vaccinations compared to non-caregivers (Brown et al., 2021).

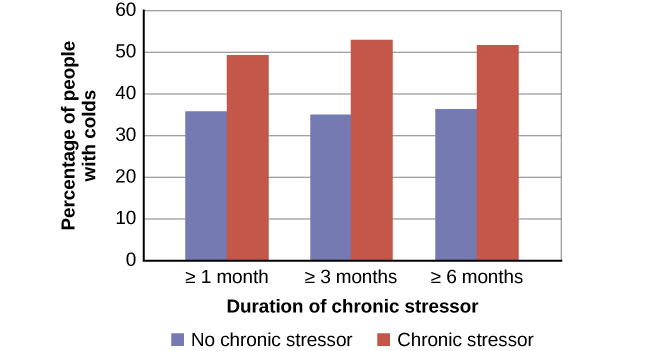

In one memorable experiment using this method, researchers interviewed 276 healthy volunteers about recent stressful experiences (Cohen et al., 1998). Following the interview, these participants were given nasal drops containing the cold virus (in case you are wondering why anybody would ever want to participate in a study in which they are asked to sniff cold viruses up their nose, the participants were paid $800 for their trouble). When examined later, participants who reported experiencing chronic stressors for more than one month — especially enduring difficulties involving work or relationships — were considerably more likely to have developed colds than were participants who reported no chronic stressors (Figure WB.14).

In another study, older volunteers were given an influenza virus vaccination. Compared to controls, those who were caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease (and thus were under chronic stress) showed poorer antibody response following the vaccination (Kiecolt-Glaser, et al., 1996).

Other studies have demonstrated that stress slows down wound healing by impairing immune responses important to wound repair (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Thompson et al., 2019). In one study, for example, skin blisters were induced on the forearm. Subjects who reported higher levels of stress produced lower levels of immune proteins necessary for wound healing (Glaser et al., 1999). Stress is not the direct force that causes harm; instead, it wears down your body’s defenses, much like how a persistent battering weakens a fortress wall, with your immune system acting as that wall.

In conclusion, the body of research from the past few years continues to support the notion that stress can significantly impact immune functioning. Stress acts not as a direct harmful agent but as a factor that weakens the body’s immune defences.

Summary

This section delves into the intricate relationship between stress and its long-term effects on health and illness. It begins by introducing the concept of biological embedding, which explains how stressors, especially in early life, can have lasting impacts on our biological systems. The section further explores Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their significant role in shaping health outcomes across a lifespan. The concepts of allostasis and allostatic load are discussed to illustrate the body’s adaptive mechanisms to stress and the physiological consequences of chronic stress exposure. The narrative challenges the dismissive attitude of “just get over it” towards stress, emphasising the importance of acknowledging and addressing the profound effects of chronic stress, as highlighted in a video on how chronic stress harms your body.

The relationship between stress and the immune system is examined in detail, including how mental stress can weaken immunity, as presented in a video discussing the effect of stress on the immune system. The section also covers how various stressors can influence immune function, setting the stage for understanding the complex interplay between psychological stressors, the body’s stress response systems, and overall health.

With these insights about biological embedding and allostatic load in mind, consider how this information applies to your life. How have early life experiences shaped your current stress levels and health for better or worse?

Image Attributions

Figure WB.13. Cold virus study by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure WB.14. Figure 14.15 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).