Chapter 17. Well-being

Mind-Body Psychophysiological Disorders

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 82 minutes

When stress reactions are frequent or particularly intense, they can gradually wear down the body, much like how playing music at a high volume on your headphones for extended periods can eventually damage your hearing. Consider a student facing intense exam stress; this might lead to elevated blood pressure, which over time can negatively impact heart health, potentially leading to heart-related issues. Additionally, chronic stress can lead to an overproduction of cortisol, a stress hormone. Elevated cortisol levels can weaken the immune system, increasing susceptibility to common illnesses like colds (McEwen, 1998). It’s important for students to be aware of these effects and find effective ways to manage stress.

Neuroscientists Robert Sapolsky and Carol Shively have conducted extensive research on stress in non-human primates for over 30 years. Both have shown that position in the social hierarchy predicts stress, mental health status, and disease. Their research sheds light on how stress may lead to negative health outcomes for stigmatised or ostracised people. Optional, here is an excellent (1 hour) in-depth documentary featuring Dr. Sapolsky, who discusses how stress can be deadly. Stress, Portrait of a Killer – Full Documentary (2008).

Physical disorders or diseases whose symptoms are brought about or worsened by stress and emotional factors are called psychophysiological disorders. The physical symptoms of psychophysiological disorders are real and they can be produced or exacerbated by psychological factors (hence the “psycho” and “physio” in psychophysiological). A list of frequently encountered psychophysiological disorders is provided in Table WB.2.

| Type of Psychophysiological Disorder | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | hypertension, coronary heart disease |

| Gastrointestinal | irritable bowel syndrome |

| Respiratory | asthma, allergy |

| Musculoskeletal | low back pain, tension headaches |

| Skin | acne, eczema, psoriasis |

Table adapted from Everly and Lating (2002).

Personality Types and Disease

Personality traits can significantly influence our physical health. Traits like negative affectivity or neuroticism, anger, and hostility can increase the risk of serious health issues, including cardiovascular diseases and chronic conditions. On the other hand, optimism is often linked to better health outcomes and a lower risk of such diseases.

For example, Friedman and Booth-Kewley (1987) statistically reviewed 101 studies to examine the link between personality and illness. They proposed the existence of disease-prone personality characteristics, including depression, anger/hostility, and anxiety. Indeed, a study of over 61,000 Norwegians identified depression as a risk factor for all major disease-related causes of death (Mykletun et al., 2007). In addition, neuroticism — a personality trait that reflects how anxious, moody, and sad one is — has been identified as a risk factor for chronic health problems and mortality (Ploubidis & Grundy, 2009).

Negative Affectivity/Neuroticism

- Increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

- Higher likelihood of chronic conditions like hypertension and asthma.

- Greater susceptibility to mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety, which can exacerbate physical health issues.

- Neuroticism tends to have a negative impact on health, primarily through stress-related pathways and unhealthy behaviours.

Anger/Hostility

- Strongly linked to cardiovascular diseases, including coronary heart disease.

- Associated with hypertension and increased risk of stroke.

- Anger and hostility are particularly detrimental to cardiovascular health, likely due to their physiological impacts on the heart and blood vessels, as well as potential negative lifestyle choices.

Optimism

- Generally associated with better health outcomes.

- Linked to lower rates of cardiovascular disease.

- May contribute to longer lifespan and better recovery from illnesses.

- Optimism appears to protect against various health issues, especially cardiovascular diseases, possibly due to healthier lifestyle choices, better stress management, and stronger social support.

Understanding the connection between personality traits and health can highlight the importance of psychological well-being in maintaining physical health. While traits like neuroticism and hostility may pose health risks, optimism offers a protective effect, underscoring the potential benefits of positive psychological states and behaviours on our overall health (Smith & MacKenzie, 2006).

Next, we will discuss psychophysiological disorders about which a great deal is known: headaches, cardiovascular disorders, and asthma. First, however, it is necessary to turn our attention to a discussion of the immune system — one of the major pathways through which stress and emotional factors can lead to illness and disease.

Heart Health and Depression

Do you know that I went down to the ground,

landed on both my broken-hearted knees.

I didn’t even cry ’cause pieces of me had already died.

— Ghost, Ingrid Michaelson, popular singer and songwriter

For centuries, poets and folklore have asserted that there is a connection between moods and the heart (Glassman & Shapiro, 1998). You are no doubt familiar with the notion of a broken heart following a disappointing or depressing event. In addition to the verse quoted above by popular singer, Ingrid Michaelson, you likely have encountered the same theme in songs, movies, and literature.

According to Avicenna, a physician who lived c. 980–1037, the main causes of depressive events are deeply rooted in heart diseases. He believed that the heart is not only a vital organ for physical health but also plays a crucial role in mental well-being. In his view, any disturbance or illness affecting the heart could have direct implications on mental health, leading to conditions like depression. Modern medicine now recognises the bidirectional relationship between mental health and heart disease. For instance, depression can lead to poor lifestyle choices, increased inflammation, and hormonal imbalances, which can exacerbate heart disease. Conversely, the stress of dealing with a chronic condition like heart disease can lead to depression (Yousofpour, et al., 2015).

In Traditional Chinese Medicine the heart and liver play a crucial role in depression and heart disease (Chen, 2014). BXQD, a Chinese herbal formula, showed improvement in symptoms of depression and cardiac prognosis in patients with co-morbid depression and coronary health issues (Wang, Liu, Li, Guo, & Wang, 2020)

Ancient Mesoamerican medicine, which existed before European influence in the Americas, recognised depression. They believed that changes in the heart were responsible for this condition. This idea shows that long ago, people understood the connection between our emotions and physical health. They saw the heart as more than just an organ; it was also considered central to our feelings and spiritual life. This old way of thinking is similar to how we now understand the link between our mental state and heart health (Rodríguez-Landa, Pulido-Criollo, & Saavedra, 2007).

Psychological research over the years has consistently shown a link between mental health conditions like depression and the risk of heart disease. One of the earliest studies in this area was by Malzberg in 1937, who found that patients with a form of depression known as “involution melancholia” had a higher death rate from heart diseases compared to the general population (Malzberg, 1937). A classic study in the late 1970s looked at over 8,000 people diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder (now classified as bipolar disorder) in Denmark, finding a nearly 50% increase in deaths from heart disease among these patients compared with the general Danish population (Weeke, & Vaeth, 1986). More recent research has further confirmed the strong relationship between depression and heart diseases, indicating that depression is a significant risk factor for developing coronary artery disease and stroke (Nemeroff, 2008; Gasse, Laursen, & Baune, 2014).

Studies have found a strong link between depression and heart disease. For example, research shows that people with depression are more likely to have heart problems. Men with depression have a 50% higher chance of dying from heart issues, and for women, the risk is even higher at 70% (Ösby et al., 2001). Another study found that people who are often depressed have a 64% higher chance of getting heart disease compared to those who are less depressed (Wulsin & Singal, 2003). Also, a large study with over 63,000 nurses showed that those who were more depressed at the start of the study had a 49% higher chance of dying from heart disease over 12 years (Whang et al., 2009). The American Heart Association, knowing how important depression is in heart disease, now recommends that all heart disease patients get checked for depression (Lichtman et al., 2008; AHA, 2014).

Additionally, depression can lead to unhealthy lifestyles, especially if it starts in childhood. A study found that teenagers who were diagnosed with depression as children were more likely to be overweight, smoke, and not exercise enough, which are all risk factors for heart disease (Rottenberg et al., 2014).

Are You Type A or Type B?

Sometimes research ideas and theories emerge from seemingly trivial observations. In the 1950s, cardiologist Meyer Friedman was looking over his waiting room furniture, which consisted of upholstered chairs with armrests. Friedman decided to have these chairs reupholstered. When the person doing the reupholstering came to the office to do the work, they commented on how the chairs were worn in a unique manner — the front edges of the cushions were worn down, as were the front tips of the arm rests. It seemed like the cardiology patients were tapping or squeezing the front of the armrests, as well as literally sitting on the edge of their seats (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). Were cardiology patients somehow different from other types of patients? If so, how?

After researching this matter, Friedman and his colleague, Ray Rosenman, came to understand that people who are prone to heart disease tend to think, feel, and act differently from those who are not. These individuals tend to be intensively driven workaholics who are preoccupied with deadlines and always seem to be in a rush. According to Friedman and Rosenman, these individuals exhibit a Type A behaviour pattern; those who are more relaxed and laid-back were characterised as Type B. In a sample of Type As and Type Bs, Friedman and Rosenman were startled to discover that heart disease was over seven times more frequent among the Type As than the Type Bs (Friedman & Rosenman, 1959).

The major components of the Type A pattern include an aggressive and chronic struggle to achieve more and more in less and less time (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). Specific characteristics of the Type A pattern include an excessive competitive drive, chronic sense of time urgency, impatience, and hostility toward others (particularly those who get in the person’s way).

Watch this video: Clip from Emotion, Stress, and Health: Crash Course Psychology #26 (5.5 minutes), video starts at minute 4:52.

“Emotion, Stress, and Health: Crash Course Psychology #26” video by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

By the 1970s, a majority of practicing cardiologists believed that Type A behaviour pattern was a significant risk factor for heart disease (Friedman, 1977). Indeed, a number of early longitudinal investigations demonstrated a link between Type A behaviour pattern and later development of heart disease (Rosenman et al., 1975; Haynes, Feinleib, & Kannel, 1980).

Subsequent research examining the association between Type A and heart disease, however, failed to replicate these earlier findings (Glassman, 2007; Myrtek, 2001). Because Type A theory did not pan out as well as they had hoped, researchers shifted their attention toward determining if any of the specific elements of Type A predict heart disease.

Extensive research clearly suggests that the anger/hostility dimension of Type A behaviour pattern may be one of the most important factors in the development of heart disease. This relationship was initially described in the Haynes et al. (1980) study mentioned above; suppressed hostility was found to substantially elevate the risk of heart disease for both men and women. Also, one investigation followed over 1,000 male medical students from 32 to 48 years. At the beginning of the study, these men completed a questionnaire assessing how they react to pressure; some indicated that they respond with high levels of anger, whereas others indicated that they respond with less anger. Decades later, researchers found that those who earlier had indicated the highest levels of anger were over 6 times more likely than those who indicated less anger to have had a heart attack by age 55, and they were 3.5 times more likely to have experienced heart disease by the same age (Chang, Ford, Meoni, Wang, & Klag, 2002). From a health standpoint, it clearly does not pay to be an angry person.

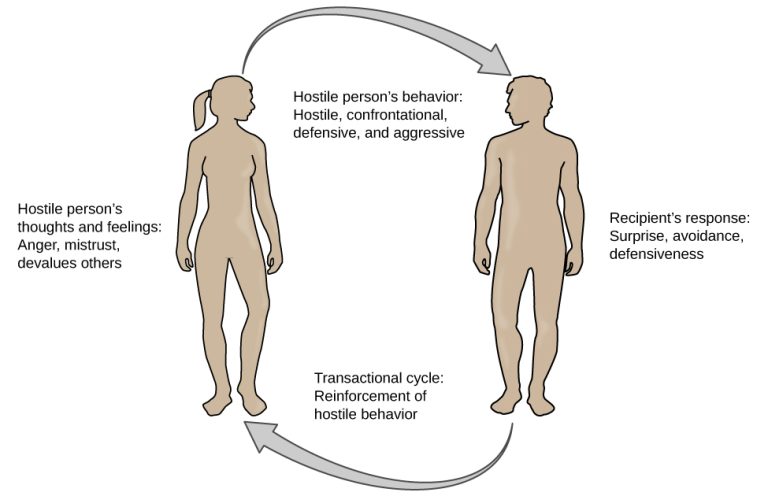

After reviewing and statistically summarising 35 studies from 1983 to 2006, Chida and Steptoe (2009) concluded that the bulk of the evidence suggests that anger and hostility constitute serious long-term risk factors for adverse cardiovascular outcomes among both healthy individuals and those already suffering from heart disease. One reason angry and hostile moods might contribute to cardiovascular diseases is that such moods can create social strain, mainly in the form of antagonistic social encounters with others. This strain could then lay the foundation for disease-promoting cardiovascular responses among hostile individuals (Vella, Kamarck, Flory, & Manuck, 2012). In this transactional model, hostility and social strain form a cycle (Figure W.17).

In addition to anger and hostility, a number of other negative emotional states have been linked with heart disease, including negative affectivity and depression (Suls & Bunde, 2005). Negative affectivity is a tendency to experience distressed emotional states involving anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear, and nervousness (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). It has been linked with the development of both hypertension and heart disease.

For example, over 3,000 initially healthy participants in one study were tracked longitudinally, for up to 22 years. Those with higher levels of negative affectivity at the time the study began were substantially more likely to develop and be treated for hypertension during the ensuing years than were those with lower levels of negative affectivity (Jonas & Lando, 2000). In addition, a study of over 10,000 middle-aged London-based civil servants who were followed an average of 12.5 years revealed that those who earlier had scored in the upper third on a test of negative affectivity were 32% more likely to have experienced heart disease, heart attack, or angina over a period of years than were those who scored in the lowest third (Nabi, Kivimaki, De Vogli, Marmot, & Singh-Manoux, 2008). Hence, negative affectivity appears to be a potentially vital risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disorders.

Other Diseases Interact with Mental Health

The intricate relationship between physical illnesses and mental health is a critical area of study, revealing how various diseases can both influence and be influenced by psychological factors. The following optional supplements explore the connections between cardiovascular disorders, headaches, and asthma, and mental health, highlighting the complex interplay between the body’s physiological responses and psychological stress, and underscoring the importance of a holistic approach to health that considers both physical and mental factors.

Summary

This section explores the relationship between stress and health. We begin by discussing how frequent or intense stress reactions can wear down the body over time, leading to issues like elevated blood pressure and weakened immunity. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels are highlighted as significant factors in this process.

Research by neuroscientists Robert Sapolsky and Carol Shively is reviewed, illustrating how social hierarchy and stress can influence health outcomes. Their findings underscore the impact of stress on mental health and disease, particularly among marginalized groups.

The chapter introduces psychophysiological disorders, which are physical ailments exacerbated by stress and emotional factors. Disorders such as hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome, asthma, and skin conditions are examined to show how psychological stress manifests physically.

We delve into how personality traits, like negative affectivity, neuroticism, anger, and hostility, can influence health. Traits linked to higher stress levels are associated with increased risks for cardiovascular diseases and other chronic conditions. Conversely, optimism is shown to have protective health benefits.

Next, we discuss the back and forth relationship between heart health and mental well-being. Historical and modern perspectives highlight how depression and other mental health issues can exacerbate heart disease, while heart disease can also lead to depression, illustrating a complex interplay between physical and mental health.

Lastly, we examine how different personality types, specifically Type A and Type B behaviour patterns, relate to stress and heart disease. Research on Type A behaviour highlights its association with higher risks of heart disease due to traits like aggression, urgency, and hostility, emphasizing the need for stress management and healthier lifestyle choices.

In the next section we will explore how to regulate stress.

Image Attributions

Figure WB.15. Heart health and depression in nurses by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure WB.16. Figure 14.19 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).