Chapter 19. Treatment of Psychological Disorders

Psychological Approaches to Treatment

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 42 minutes

Treatment for psychological disorder begins when the individual who is experiencing distress visits a counselor or therapist, perhaps in a church, a community centre, a hospital, or a private practice. The therapist will begin by systematically learning about the patient’s needs through a formal psychological assessment, which is an evaluation of the patient’s psychological and mental health. During the assessment the psychologist may give personality tests such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personal Inventory (MMPI-2), Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI), or projective tests, and will conduct a thorough interview with the patient. The therapist may get more information from family members or school personnel.

In addition to the psychological assessment, the patient is usually seen by a physician to gain information about potential Axis III (physical) problems. In some cases of psychological disorder — and particularly for sexual problems — medical treatment is the preferred course of action. For instance, men who are experiencing erectile dysfunction disorder may need surgery to increase blood flow or local injections of muscle relaxants. Or they may be prescribed medications (Viagra, Cialis, or Levitra) that provide an increased blood supply to the penis, and are successful in increasing performance in about 70% of men who take them.

After the medical and psychological assessments are completed, the therapist will make a formal diagnosis using the detailed descriptions of the disorder provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The therapist will summarise the information about the patient on each of the five DSM axes, and the diagnosis will likely be sent to an insurance company to justify payment for the treatment.

If a diagnosis is made, the therapist will select a course of therapy that he or she feels will be most effective. One approach to treatment is psychotherapy, the professional treatment for psychological disorder through techniques designed to encourage communication of conflicts and insight. The fundamental aspect of psychotherapy is that the patient directly confronts the disorder and works with the therapist to help reduce it. Therapy includes assessing the patient’s issues and problems, planning a course of treatment, setting goals for change, the treatment itself, and an evaluation of the patient’s progress. Therapy is practiced by thousands of psychologists and other trained practitioners in Canada and around the world, and is responsible for billions of dollars of the health budget.

There is a stereotype that therapy must involve a patient lying on a couch with a therapist sitting behind and nodding sagely as the patient speaks. Though this approach to therapy (known as psychoanalysis) is still practiced, it is in the minority. It is estimated that there are over 400 different kinds of therapy practiced by people in many fields, and the most important of these are psychodynamic, humanistic, cognitive behavioural therapy, and eclectic (i.e., a combination of therapies). The therapists who provide these treatments include psychiatrists (who have a medical degree and can prescribe drugs) and clinical psychologists, as well as social workers, psychiatric nurses, and couples, marriage, and family therapists.

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Psychological Treatments (6 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Psychological Treatments” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Here is the Tricky Topics: Psychological Treatments transcript.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy (psychoanalysis) is a psychological treatment based on Freudian and neo-Freudian personality theories in which the therapist helps the patient explore the unconscious dynamics of personality. The analyst engages with the patient, usually in one-on-one sessions, often with the patient lying on a couch and facing away. The goal of the psychotherapy is for the patient to talk about their personal concerns and anxieties, allowing the therapist to try to understand the underlying unconscious problems that are causing the symptoms (the process of interpretation). The analyst may try out some interpretations on the patient and observe how he or she responds to them.

The patient may be asked to verbalise their thoughts through free association, in which the therapist listens while the client talks about whatever comes to mind, without any censorship or filtering. The client may also be asked to report on his or her dreams, and the therapist will use dream analysis to analyze the symbolism of the dreams in an effort to probe the unconscious thoughts of the client and interpret their significance. On the basis of the thoughts expressed by the patient, the analyst discovers the unconscious conflicts causing the patient’s symptoms and interprets them for the patient.

The goal of psychotherapy is to help the patient develop insight — that is, an understanding of the unconscious causes of the disorder (Epstein, Stern, & Silbersweig, 2001; Lubarsky & Barrett, 2006), but the patient often shows resistance to these new understandings, using defence mechanisms to avoid the painful feelings in his or her unconscious. The patient might forget or miss appointments, or act out with hostile feelings toward the therapist. The therapist attempts to help the patient develop insight into the causes of the resistance. The sessions may also lead to transference, in which the patient unconsciously redirects feelings experienced in an important personal relationship toward the therapist. For instance, the patient may transfer feelings of guilt that come from the father or mother to the therapist. Some therapists believe that transference should be encouraged, as it allows the client to resolve hidden conflicts and work through feelings that are present in the relationships.

One problem with traditional psychoanalysis is that the sessions may take place several times a week, go on for many years, and cost thousands of dollars. To help more people benefit, modern psychodynamic approaches frequently use shorter-term, focused, and goal-oriented approaches. In these brief psychodynamic therapies, the therapist helps the client determine the important issues to be discussed at the beginning of treatment and usually takes a more active role than in classic psychoanalysis (Levenson, 2010).

Counter-transference and why psychotherapists on TV shows should not sleep with their patients

Counter-transference occurs when therapists project their own unresolved feelings, beliefs, or experiences onto their patients, usually in response to transference from the patient. This dynamic can be conscious or unconscious and often stems from the therapist’s own emotional reactions to the themes and issues presented by the patient during therapy sessions. Effective therapists recognise and manage these reactions to prevent them from interfering with the therapeutic process. Instead, they use their understanding of counter-transference as a therapeutic tool to deepen their empathy and enhance their insight into the patient’s experience, thereby facilitating a more informed and sensitive intervention. In marked contrast to what is popular shown on TV shows, therapists must recognise and address their counter-transference because it is crucial for maintaining professional boundaries and ensuring that the therapy focuses on the patient’s needs and therapeutic goals. In short, TV therapists — and all professionals in real life — should never ever sleep with their patients.

Humanistic Therapies

Just as psychoanalysis is based on the personality theories of Freud and the neo-Freudians, humanistic therapy is a psychological treatment based on the personality theories of Carl Rogers and other humanistic psychologists. Humanistic therapy is based on the idea that people develop psychological problems when they are burdened by limits and expectations placed on them by themselves and others; the treatment emphasises the person’s capacity for self-realisation and fulfillment. Humanistic therapies attempt to promote growth and responsibility by helping clients consider their own situations and the world around them and how they can work to achieve their life goals.

Carl Rogers developed person-centred therapy (or client-centred therapy), an approach to treatment in which the client is helped to grow and develop as the therapist provides a comfortable, nonjudgmental environment. In his book A Way of Being (1980), Rogers argued that therapy was most productive when the therapist created a positive relationship with the client — a therapeutic alliance. The therapeutic alliance is a relationship between the client and the therapist that is facilitated when the therapist is genuine (i.e., they create no barriers to free-flowing thoughts and feelings), when the therapist treats the client with unconditional positive regard (i.e., they value the client without any qualifications, displaying an accepting attitude toward whatever the client is feeling at the moment), and when the therapist develops empathy with the client (i.e., they actively listen to and accurately perceive the personal feelings that the client experiences).

The development of a positive therapeutic alliance has been found to be exceedingly important to successful therapy. The ideas of genuineness, empathy, and unconditional positive regard in a nurturing relationship, in which the therapist actively listens to and reflects the feelings of the client, is probably the most fundamental part of contemporary psychotherapy (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Psychodynamic and humanistic therapies are recommended primarily for people suffering from generalised anxiety or mood disorders, and who desire to feel better about themselves overall. But the goals of people with other psychological disorders, such as phobias, sexual problems, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), are more specific. A person with a social phobia may want to be able to leave their house, a person with a sexual dysfunction may want to improve their sex life, and a person with OCD may want to learn to stop letting their obsessions or compulsions interfere with everyday activities. In these cases it is not necessary to revisit childhood experiences or consider our capacities for self-realisation — we simply want to deal with what is happening in the present.

Psychotherapy

Play Therapy

Play therapy is often used with children since they are not likely to sit on a couch and recall their dreams or engage in traditional talk therapy. This technique uses a therapeutic process of play to “help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties and achieve optimal growth” (O’Connor, 2000, p. 7). The idea is that children play out their hopes, fantasies, and traumas while using dolls, stuffed animals, and sandbox figurines (Figure PY.6). Play therapy can also be used to help a therapist make a diagnosis. The therapist observes how the child interacts with toys (e.g., dolls, animals, and home settings) in an effort to understand the roots of the child’s disturbed behaviour. Play therapy can be nondirective or directive. In nondirective play therapy, children are encouraged to work through their problems by playing freely while the therapist observes (LeBlanc & Ritchie, 2001). In directive play therapy, the therapist provides more structure and guidance in the play session by suggesting topics, asking questions, and even playing with the child (Harter, 1977).

Behaviour Therapy

In psychoanalysis, therapists help their patients look into their past to uncover repressed feelings. In behaviour therapy, a therapist employs principles of learning to help clients change undesirable behaviours, rather than digging deeply into one’s unconscious. Therapists with this orientation believe that dysfunctional behaviours, like phobias and bedwetting, can be changed by teaching clients new, more constructive behaviours. Behaviour therapy employs both classical and operant conditioning techniques to change behaviour.

One type of behaviour therapy utilises classical conditioning techniques. Therapists using these techniques believe that dysfunctional behaviours are conditioned responses. Applying the conditioning principles developed by Ivan Pavlov, these therapists seek to recondition their clients and thus change their behaviour.

For example: Feng is eight years old and frequently wets his bed at night. Feng has been invited to several sleepovers but won’t go because of this problem. Using a type of conditioning therapy, Feng begins to sleep on a liquid-sensitive bed pad that is connected to a sound alarm. When moisture touches the pad, it causes the alarm to sound, waking up Feng. When this process is repeated enough times, Feng develops an association between urinary relaxation and waking up, and this leads to the discontinuation of the bedwetting. Feng has now gone three weeks without wetting the bed and is looking forward to his first sleepover this weekend.

One commonly used classical conditioning therapeutic technique is counterconditioning; a client learns a new response to a stimulus that has previously elicited an undesirable behaviour. Two counterconditioning techniques are aversive conditioning and exposure therapy. Aversive conditioning uses an unpleasant stimulus to stop an undesirable behaviour. Therapists apply this technique to eliminate addictive behaviours, such as smoking, nail biting, and drinking. In aversion therapy, clients will typically engage in a specific behaviour (such as nail biting) and at the same time are exposed to something unpleasant, such as a mild electric shock or a bad taste. After repeated associations between the unpleasant stimulus and the behaviour, the client can learn to stop the unwanted behaviour.

Aversion therapy has been used effectively for years in the treatment of alcoholism (Davidson, 1974; Elkins, 1991; Streeton & Whelan, 2001). One common way this occurs is through a chemically based substance known as Antabuse. When a person takes Antabuse and then consumes alcohol, uncomfortable side effects result including nausea, vomiting, increased heart rate, heart palpitations, severe headache, and shortness of breath. Antabuse is repeatedly paired with alcohol until the client associates alcohol with unpleasant feelings, which decreases the client’s desire to consume alcohol. Antabuse creates a conditioned aversion to alcohol because it replaces the original pleasure response with an unpleasant one.

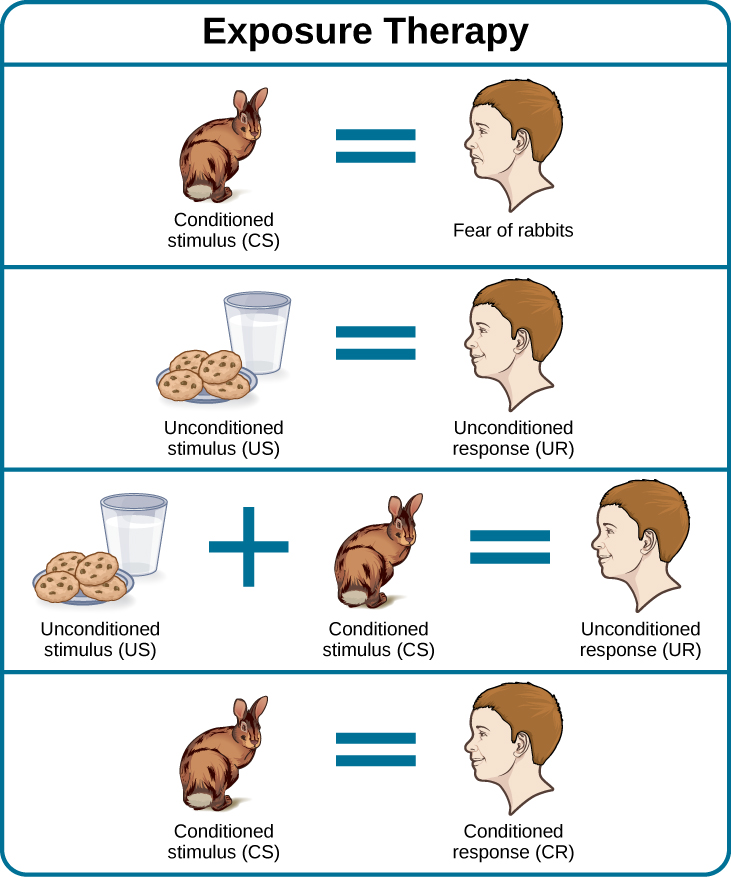

In exposure therapy, a therapist seeks to treat clients’ fears or anxiety by presenting them with the object or situation that causes their problem, with the idea that they will eventually get used to it. This can be done via reality, imagination, or virtual reality. Exposure therapy was first reported in 1924 by Mary Cover Jones, who is considered the mother of behaviour therapy. Jones worked with a boy named Peter who was afraid of rabbits. Her goal was to replace Peter’s fear of rabbits with a conditioned response of relaxation, which is a response that is incompatible with fear (Figure PY.7). How did she do it? Jones began by placing a caged rabbit on the other side of a room with Peter while he ate his afternoon snack. Over the course of several days, Jones moved the rabbit closer and closer to where Peter was seated with his snack. After two months of being exposed to the rabbit while relaxing with his snack, Peter was able to hold the rabbit and pet it while eating (Jones, 1924).

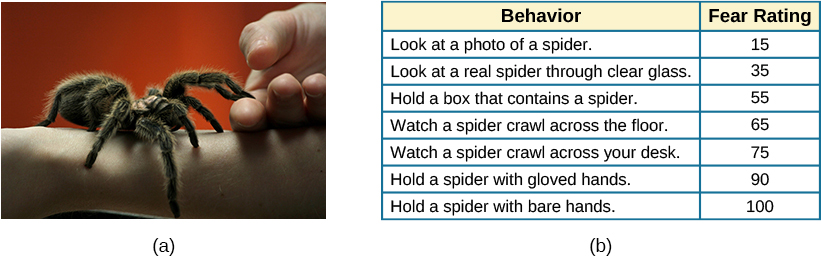

Thirty years later, Joseph Wolpe (1958) refined Jones’s techniques, giving us the behaviour therapy technique of exposure therapy that is used today. A popular form of exposure therapy is systematic desensitization, wherein a calm and pleasant state is gradually associated with increasing levels of anxiety-inducing stimuli. The idea is that you can’t be nervous and relaxed at the same time. Therefore, if you can learn to relax when you are facing environmental stimuli that make you nervous or fearful, you can eventually eliminate your unwanted fear response (Wolpe, 1958) (Figure PY.8).

How does exposure therapy work? Jayden is terrified of elevators. Nothing bad has ever happened to Jayden on an elevator, but they’re so afraid of elevators that they will always take the stairs. That wasn’t a problem when Jayden worked on the second floor of an office building, but now they have a new job—on the 29th floor of a skyscraper in downtown Los Angeles. Jayden knows they can’t climb 29 flights of stairs in order to get to work each day, so they decided to see a behaviour therapist for help. The therapist asks Jayden to first construct a hierarchy of elevator-related situations that elicit fear and anxiety. They range from situations of mild anxiety such as being nervous around the other people in the elevator, to the fear of getting an arm caught in the door, to panic-provoking situations such as getting trapped or the cable snapping. Next, the therapist uses progressive relaxation, teaching Jayden how to relax each of their muscle groups so that they achieve a drowsy, relaxed, and comfortable state of mind. Once Jayden’s in this state, the therapist asks Jayden to imagine a mildly anxiety-provoking situation. Jayden is standing in front of the elevator thinking about pressing the call button.

If this scenario causes Jayden anxiety, then they lift their finger. The therapist would then tell Jayden to forget the scene and return to their relaxed state. The therapist repeats this scenario over and over until Jayden can imagine pressing the call button without anxiety. Over time the therapist and Jayden use progressive relaxation and imagination to proceed through all of the situations on Jayden’s hierarchy until they become desensitised to each one. After this, Jayden and the therapist begin to practice what Jayden only previously envisioned in therapy, gradually going from pressing the button to actually riding an elevator. The goal is that Jayden will soon be able to take the elevator all the way up to the 29th floor of their office without feeling any anxiety.

Sometimes, it’s too impractical, expensive, or embarrassing to re-create anxiety-producing situations, so a therapist might employ virtual reality exposure therapy by using a simulation to help conquer fears. Virtual reality exposure therapy has been used effectively to treat numerous anxiety disorders such as the fear of public speaking, claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces), aviophobia (fear of flying), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a trauma and stressor-related disorder (Gerardi, Cukor, Difede, Rizzo, & Rothbaum, 2010).

Using virtual reality to help patients with dementia

Watch this video from Global News that highlights work being done at York University using virtual reality with patients with dementia.

Some behaviour therapies use operant conditioning, a technique that modifies behaviour through rewards and consequences. Recall what you learned about operant conditioning — we have a tendency to repeat behaviours that are reinforced. What happens to behaviours that are not reinforced? They become extinguished. These principles, defined by Skinner as operant conditioning, can be applied to help people with a wide range of psychological problems. For instance, operant conditioning techniques designed to reinforce desirable behaviours and punish unwanted behaviours are effective behaviour modification tools to help children with autism (Lovaas, 1987, 2003; Sallows & Graupner, 2005; Wolf & Risley, 1967).

This technique is called Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA). In this treatment, a child’s behaviour is charted and analysed. The ABA therapist, along with the caregivers, determines what reinforces the child, what sustains a behaviour to continue, and how best to manage a behaviour. For example, Nur may become overwhelmed and run out of the room when the classroom is too noisy. Whenever Nur runs out of the classroom, the teacher’s aide chases after them and places Nur in a special room where they can relax. Going into the special room and getting the aide’s attention are reinforcing for Nur. In order to change Nur’s behaviour, Nur must be presented with other options before they become overwhelmed, and they cannot receive reinforcement for displaying maladaptive behaviours.

One popular operant conditioning intervention is called the token economy. This involves a controlled setting where individuals are reinforced for desirable behaviours with tokens, such as a poker chip, that can be exchanged for items or privileges. Token economies are often used in psychiatric hospitals to increase patient cooperation and activity levels. Patients are rewarded with tokens when they engage in positive behaviours (e.g., making their beds, brushing their teeth, coming to the cafeteria on time, and socialising with other patients). They can later exchange the tokens for extra TV time, private rooms, visits to the canteen, and so on (Dickerson, Tenhula, & Green-Paden, 2005).

Psychotherapy: Cognitive Therapy

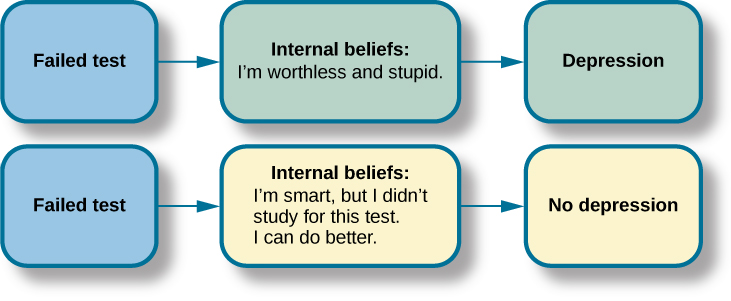

Cognitive therapy is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on how a person’s thoughts lead to feelings of distress. The idea behind cognitive therapy is that how you think determines how you feel and act. Cognitive therapists help their clients change dysfunctional thoughts in order to relieve distress. They help a client see how they misinterpret a situation (cognitive distortion). For example, a client may overgeneralise. Because Rey failed one test in Psychology 101, Rey feels they are stupid and worthless. These thoughts then cause their mood to worsen. Therapists also help clients recognise when they blow things out of proportion. Because Rey failed their Psychology 101 test, they have concluded that they’re going to fail the entire course and probably flunk out of college altogether. These errors in thinking have contributed to Rey’s feelings of distress. Rey’s therapist will help them challenge these irrational beliefs, focus on their illogical basis, and correct them with more logical and rational thoughts and beliefs.

Cognitive therapy was developed by psychiatrist Aaron Beck in the 1960s. His initial focus was on depression and how a client’s self-defeating attitude served to maintain a depression despite positive factors in her life (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) (Figure PY.9). Through questioning, a cognitive therapist can help a client recognise dysfunctional ideas, challenge catastrophising thoughts about themselves and their situations, and find a more positive way to view things (Beck, 2011).

More About Cognitive Therapy

Watch as Dr. Aaron Beck explains Cognitive Therapy and gives some examples of its use, to learn more.

Psychotherapy: Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive-behavioural therapists focus much more on present issues than on a patient’s childhood or past, as in other forms of psychotherapy. One of the first forms of cognitive-behavioural therapy was rational emotive therapy (RET), which was founded by Albert Ellis and (like Beck’s development of Cognitive Therapy) grew out of his dislike of Freudian psychoanalysis (Daniel, n.d.). Behaviourists such as Joseph Wolpe also influenced Ellis’s therapeutic approach (National Association of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapists, 2009).

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) helps clients examine how their thoughts affect their behaviour. It aims to change cognitive distortions and self-defeating behaviours. In essence, this approach is designed to change the way people think as well as how they act. It is similar to cognitive therapy in that CBT attempts to make individuals aware of their irrational and negative thoughts and helps people replace them with new, more positive ways of thinking. It is also similar to behaviour therapies in that CBT teaches people how to practice and engage in more positive and healthy approaches to daily situations.

In total, hundreds of studies have shown the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy in the treatment of numerous psychological disorders such as depression, PTSD, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse (Beck Institute for Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, n.d.). For example, CBT has been found to be effective in decreasing levels of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts in previously suicidal teenagers (Alavi, Sharifi, Ghanizadeh, & Dehbozorgi, 2013). Cognitive-behavioural therapy has also been effective in reducing PTSD in specific populations, such as transit workers (Lowinger & Rombom, 2012).

Cognitive-behavioural therapy aims to change cognitive distortions and self-defeating behaviours using techniques like the ABC model. With this model, there is an:

- Action (sometimes called an activating event), the

- Belief about the event, and the

- Consequences of this belief.

Let’s say Jude and Zain both go to a party. Jude and Zain have each met someone new at the party and both of them spend a few hours chatting with their new acquaintances. At the end of the party, both Jude and Zain ask the new person they’ve met for their phone number, but in both cases, the other person refuses. Both Jude and Zain are surprised, as they both thought things were going well. What might Jude and Zain tell themselves about why the person was not interested? Let’s say Jude tells himself that he is a loser, or is ugly, or “has no game”. Jude then gets depressed and decides not to go to another party, which starts a cycle that keeps him depressed. Zain, on the other hand, thinks that maybe it was bad breath and goes out and buys some breath mints, goes to another party, and meets someone new.

Jude’s belief about what happened results in a consequence of further depression, whereas Zain’s belief does not. Jude is internalising the attribution or reason for the rebuffs, which triggers his depression. On the other hand, Zain is externalising the cause, so their thinking does not contribute to feelings of depression.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy focuses on identifying and correcting maladaptive and automatic thoughts, known as cognitive distortions, which skew a person’s perception of reality. Three common types of cognitive distortions are all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralisation, and jumping to conclusions.

All-or-nothing thinking is marked by seeing situations in extremes, with no middle ground, often found in individuals experiencing depression. For example, after being rejected for a date, Jude might think, “No one will ever go out with me. I’m going to be alone forever”, leading him to feel anxious and despondent about his future prospects.

Overgeneralisation involves drawing broad conclusions from a single, often minor, event. Jude might generalise a rejection by saying, “I am ugly, a loser, and no one is ever going to be interested in me”, rather than seeing it as an isolated incident, thus magnifying the emotional impact of the rejection far beyond its actual significance.

Jumping to conclusions occurs when someone assumes a negative outcome without sufficient evidence to support such a belief. For example, when Carrigan does not hear back from Chao after leaving a message to meet for coffee, they might prematurely conclude that Chao dislikes them or is disinterested in friendship, despite many other plausible reasons for Chao’s lack of response.

How effective is CBT? One client said this about his cognitive-behavioural therapy:

I have had many painful episodes of depression in my life, and this has had a negative effect on my career and has put considerable strain on my friends and family. The treatments I have received, such as taking antidepressants and psychodynamic counselling, have helped [me] to cope with the symptoms and to get some insights into the roots of my problems. CBT has been by far the most useful approach I have found in tackling these mood problems. It has raised my awareness of how my thoughts impact on my moods. How the way I think about myself, about others and about the world can lead me into depression. It is a practical approach, which does not dwell so much on childhood experiences, whilst acknowledging that it was then that these patterns were learned. It looks at what is happening now, and gives tools to manage these moods on a daily basis. (Martin, 2007, n.p.)

Study hint: What is the difference between Cognitive therapy and Cognitive-Behavioural therapy?

Cognitive Therapy (CT): Focuses primarily on the “Thought” aspect. CT centers around identifying and changing dysfunctional thinking patterns and beliefs to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies. It helps clients recognise and change cognitive distortions that contribute to their psychological distress.

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Includes both “Thought” and “Behaviour”. CBT expands on CT by also targeting the behaviours associated with harmful thinking. This therapy not only works on changing distorted thinking but integrates behavioural techniques to alter actions that perpetuate problems. CBT addresses both the thought processes and the behaviours that are rooted in these thoughts, making it a comprehensive approach.

Integrative (Eclectic) Approaches to Therapy

Eclectic therapy integrates various psychological methods, such as cognitive-behavioural, psychodynamic, humanistic, sociocultural, feminist, and anti-oppression therapies, to create personalised treatment plans that address the unique needs of each patient. This integrative method is particularly suited to complex mental health conditions that present diverse symptoms and challenges.

Aadia’s Case: An Example of Borderline Personality Disorder

Aadia’s story exemplifies the complex and multifaceted nature of borderline personality disorder, illustrating why an eclectic approach is essential for addressing such varied symptoms effectively. From infancy, Aadia displayed intense emotional responses and severe separation anxiety, crying nonstop until a parent returned. As a teenager, these intense emotions manifested as anger and impulsivity, with Aadia frequently yelling at parents and teachers and engaging in risky behaviours such as promiscuity and running away from home. These behaviours, along with Aadia’s unstable relationships and emotional turmoil, highlight the traits commonly associated with borderline personality disorder.

By the time Aadia turned 17, their behaviour had become increasingly unpredictable, with violent outbursts and periods of intense clinginess or abrupt departures from home. After a painful breakup, Aadia’s self-harming behaviour escalated to a serious suicide attempt at the age of 18, necessitating professional psychological intervention.

Therapeutic Approach and Methods

Given the severity and variety of Aadia’s symptoms, an eclectic approach was deemed crucial to address both immediate behavioural issues and deeper psychological patterns. Initially, to stabilise Aadia’s mood and reduce the risk of further self-harm, therapists recommended antidepressant medications. However, understanding that medication alone would not resolve the underlying psychological issues, the therapeutic strategy also included comprehensive psychotherapy.

During the initial therapy sessions, the focus was primarily on building trust through person-centered approaches, facilitating a therapeutic alliance conducive to open communication. In subsequent sessions, if the therapist is trained in psychodynamic methods, they would engage Aadia in intensive face-to-face sessions to explore childhood experiences and attachment issues. At the same time, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) was employed to address Aadia’s distorted perceptions and maladaptive thought patterns, aiming to correct these and improve interpersonal relations. The therapist will work with the patient one-on-one and in group settings to help improve how they interact with others, manage their emotions, and handle stress better.

Monitoring Progress and Introducing DBT

As therapy progressed, the eclectic therapist continuously monitored Aadia’s behaviour, adapting therapeutic techniques to best meet evolving needs. The goal was to maintain engagement in therapy long enough to achieve significant progress.

An integral part of Aadia’s eclectic treatment included dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT; Linehan & Dimeff, 2001), which combines cognitive-behavioural techniques with mindfulness practices. DBT is a cognitive therapy, but it includes a particular emphasis on attempting to enlist the help of the patient in their own treatment. This approach is particularly effective in managing the intense emotional fluctuations associated with borderline personality disorder. DBT emphasises developing skills in interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance, all crucial for Aadia’s recovery.

Image Attributions

Figure PY.6. Figure 16.10 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.7. Figure 16.11 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.8. Figure 16.12 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.9. Figure 16.13 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).