Chapter 19. Treatment of Psychological Disorders

Biological Approaches to Treatment

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 28 minutes

Like other medical problems, psychological disorders may in some cases be treated biologically. Biomedical therapies are treatments designed to reduce psychological disorder by influencing the action of the central nervous system. These therapies primarily involve the use of medications but also include direct methods of brain intervention, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and psychosurgery.

Drug Therapies

Psychologists understand that an appropriate balance of neurotransmitters in the brain is necessary for mental health. If there is a proper balance of chemicals, then the person’s mental health will be acceptable, but psychological disorder will result if there is a chemical imbalance. The most frequently used biological treatments provide the patient with medication that influences the production and reuptake of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS). The use of these drugs is rapidly increasing, and drug therapy is now the most common approach to treatment of most psychological disorders.

Unlike some medical therapies that can be targeted toward specific symptoms, current psychological drug therapies are not so specific; they don’t change particular behaviours or thought processes, and they don’t really solve psychological disorders. However, although they cannot “cure” disorders, drug therapies are nevertheless useful therapeutic approaches, particularly when combined with psychological therapy, in treating a variety of psychological disorders. The best drug combination for the individual patient is usually found through trial and error (Biedermann & Fleischhacker, 2009).

The major classes and brand names of drugs used to treat psychological disorders are shown in Table PY.2.

| Type of Medication | Used to Treat | Brand Names of Commonly Prescribed Medications | How They Work | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics (developed in the 1950s) | Schizophrenia and other types of severe thought disorders | Haldol, Mellaril, Prolixin, Thorazine | Treat positive psychotic symptoms such as auditory and visual hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia by blocking the neurotransmitter dopamine | Long-term use can lead to tardive dyskinesia (involuntary movements of the face and body), and extrapyramidal symptoms (muscle stiffness, tremors similar to Parkinson’s disease). |

| Atypical Antipsychotics (developed in the late 1980s) | Schizophrenia and other types of severe thought disorders | Abilify, Risperdal, Clozaril | Treat negative symptoms of schizophrenia (like withdrawal and apathy) and sometimes positive symptoms (like hallucinations) by targeting both dopamine and serotonin receptors. | May cause weight gain, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels; other side effects include constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, drowsiness, and dizziness. |

| Anti-depressants | SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors): Depression and anxiety

SNRIs (Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors): depression and anxiety NRIs (Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors): depression and smoking cessation |

SSRIs: Prozac, Zoloft, Celexa, Lexapro, Paxil.

SNRIs: Effexor, Cymbalta, Pristiq. NRIs: Wellbutrin, Zyban, Strattera. |

SSRIs increase serotonin levels in the brain (a neurotransmitter that helps regulate mood).

SNRIs increase both serotonin and norepinephrine (a neurotransmitter related to alertness and energy). NRIs primarily increase norepinephrine levels. |

SSRIs: headache, nausea, weight gain, drowsiness, reduced sex drive.

SNRIs: nausea, dizziness, and sweating. NRIs: dry mouth, constipation, and dizziness. |

| Anti-anxiety agents | anxiety and agitation that occur in OCD, PTSD, panic disorder, and social phobia

insomnia |

Benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders: Rivotril, Xanax, Ativan, Lectopam, Serax, Librium, Tranxene, Valium.

Benzodiazepines for insomnia: Ativan, Mogadon, Serax, Restoril, Halcion, Dalmane. |

Depress central nervous system activity. This means they reduce the activity of the brain and nerves, making the body feel more relaxed and calm. They do this by enhancing the effects of a neurotransmitter called GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which is naturally calming and helps reduce feelings of anxiety and stress. | Drowsiness, dizziness, headache, fatigue, lightheadedness.

Severe withdrawal symptoms from regular use of benzodiazepines in high doses may include agitation, paranoia, delirium and seizures. |

| Mood Stabilisers | Bipolar disorder | Lithium, Depakote, Lamictal, Tegretol | Lithium moderates neurotransmitter signaling (helps stabilise mood swings). Depakote and Lamictal regulate neurotransmitter levels and electrical activity in neurons, calming overactivity. Tegretol stabilises mood by inhibiting sodium channels (reduces excessive nerve activity). | Excessive thirst, irregular heartbeat, itching/rash, swelling (face, mouth, and extremities), nausea, loss of appetite |

| Stimulants | ADHD | Adderall, Ritalin | Improve ability to focus on tasks and maintain attention by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine levels (brain chemicals that help regulate attention and alertness). | Decreased appetite, difficulty sleeping, stomachache, headache |

| Psychedelics | Depression, PTSD, anxiety, addiction | Psilocybin (Magic Mushrooms), LSD, DMT, Ayahuasca | Primarily affect serotonin receptors, which can alter perception, mood, and cognitive processes | Altered sensory perception, psychological distress, nausea |

Antipsychotic Medications

Until the middle of the 20th century, schizophrenia was inevitably accompanied by the presence of positive symptoms, including bizarre, disruptive, and potentially dangerous behaviour. As a result, schizophrenics were locked in asylums to protect them from themselves and to protect society from them. In the 1950s, a drug called chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was discovered that could reduce many of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Chlorpromazine was the first of many antipsychotic drugs.

Antipsychotic drugs (neuroleptics) are drugs that treat the symptoms of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Today there are many antipsychotics, including Thorazine, Haldol, Clozaril, Risperdal, and Zyprexa. Some of these drugs treat the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, and some treat the positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms.

The discovery of chlorpromazine and its use in clinics has been described as the single greatest advance in psychiatric care, because it has dramatically improved the prognosis of patients in psychiatric hospitals worldwide. Using antipsychotic medications has allowed hundreds of thousands of people to move out of asylums into individual households or community mental health centres, and in many cases to live near-normal lives.

Antipsychotics reduce the positive symptoms of schizophrenia by reducing the transmission of dopamine at the synapses in the limbic system, and they improve negative symptoms by influencing levels of serotonin (Marangell, Silver, Goff, & Yudofsky, 2003). Despite their effectiveness, antipsychotics have some negative side effects, including restlessness, muscle spasms, dizziness, and blurred vision. In addition, their long-term use can cause permanent neurological damage, a condition called tardive dyskinesia that causes uncontrollable muscle movements, usually in the mouth area (National Institute of Mental Health, 2008). Newer antipsychotics treat more symptoms with fewer side effects than older medications do (Casey, 1996).

Antidepressant Medications

Antidepressant medications are designed to improve mood and are predominantly used in treating depression. They are also effective in managing anxiety disorders, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. These drugs typically modify the production and uptake of neurotransmitters like serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, crucial for regulating emotion. While the detailed mechanisms are not fully understood, it is recognised that enhancing neurotransmitter levels in the central nervous system can significantly reduce symptoms of depression (Cipriani et al., 2018).

Historically, depression treatment included tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), which increase neurotransmitter availability but are associated with severe side effects, including cardiovascular risks and dietary restrictions due to potential severe interactions with certain foods.

Today, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac, Zoloft, and Celexa are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants. These drugs predominantly block the reuptake of serotonin, increasing its concentration in the central nervous system. SSRIs are preferred due to their relatively safe profile and fewer side effects compared to TCAs and MAOIs. However, they also can have significant side effects; patients may experience issues such as gastrointestinal disturbances, sexual dysfunction, and emotional blunting (Hieronymus et al., 2016).

Concerns about SSRIs potentially increasing the risk of suicidal thoughts among teens and young adults continue to be debated, with newer studies urging caution and a balanced approach to prescribing these medications in vulnerable populations (Cipriani et al., 2018). The onset of antidepressant effects can be slow, often requiring several weeks to months to be effective, necessitating tailored treatment plans for individual patients. This slow ramping up to full dose can leave patients under-medicated and suffering with their symptoms for weeks.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) like Effexor and Cymbalta, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) such as Wellbutrin, are also popular. SNRIs are known to enhance both serotonin and norepinephrine levels, improving mood and energy, while NRIs primarily increase norepinephrine, helpful in treating depression and aiding smoking cessation. These classes of antidepressants also have side effects and may cause nausea, dizziness, and insomnia (Fornaro et al., 2019).

Recent research has also explored the therapeutic potentials of psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD, DMT, and Ayahuasca for treating various psychiatric disorders including depression, PTSD and anxiety. These substances interact with serotonin receptors in the brain and have shown promise in altering perception, mood, and cognitive processes, although they can also induce significant sensory and psychological alterations (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017).

Using Stimulants to Treat ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is frequently treated with biomedical therapy, usually along with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The most commonly prescribed drugs for ADHD are psychostimulants, including Ritalin, Adderall, and Dexedrine. Short-acting forms of the drugs are taken as pills and last between 4 and 12 hours, but some of the drugs are also available in long-acting forms (skin patches) that can be worn on the hip and last up to 12 hours. The patch is placed on the child early in the morning and worn all day.

Stimulants improve the major symptoms of ADHD, including inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity, often dramatically, in about 75% of the children who take them (Greenhill, Halperin, & Abikof, 1999). But the effects of the drugs wear off quickly. Additionally, the best drug and best dosage vary from child to child, so it may take some time to find the correct combination.

It may seem surprising to you that a disorder that involves hyperactivity is treated with a psychostimulant, a drug that normally increases activity. The answer lies in the dosage. When large doses of stimulants are taken, they increase activity, but in smaller doses the same stimulants improve attention and decrease motor activity (Zahn, Rapoport, & Thompson, 1980).

The most common side effects of psychostimulants in children include decreased appetite, weight loss, sleeping problems, and irritability as the effect of the medication tapers off. Stimulant medications may also be associated with a slightly reduced growth rate in children, although in most cases growth isn’t permanently affected (Spencer, Biederman, Harding, & O’Donnell, 1996).

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Biological Treatments of Psychological Disorders (8 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Biological Treatments of Psychological Disorders” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Here is the Tricky Topics: Biological Treatments of Psychological Disorders transcript.

Mood Stabilisers: Lithium

Patients who are suffering from bipolar disorder are not helped by the SSRIs or other antidepressants because their disorder also involves the experience of overly positive moods. Treatment is more complicated for these patients, often involving a combination of antipsychotics and antidepressants along with mood stabilising medications (McElroy & Keck, 2000). The most well-known mood stabilser, lithium carbonate (or lithium), is used widely to treat mania associated with bipolar disorder. Available in Canada for more than 60 years, the medication is used to treat acute manic episodes and as a long-term therapy to reduce their frequency and severity. Anticonvulsant medications can also be used as mood stabilisers. Another drug, Depakote, has also proven very effective, and some bipolar patients may do better with it than with lithium (Kowatch et al., 2000).

People who take lithium must have regular blood tests to be sure that the levels of the drug are in the appropriate range. Potential negative side effects of lithium are loss of coordination, slurred speech, frequent urination, and excessive thirst. Though side effects often cause patients to stop taking their medication, it is important that treatment be continuous, rather than intermittent. Recently, Health Canada updated safety information and treatment recommendations for lithium after finding that taking lithium carries a risk of high blood calcium, or hypercalcemia, and is sometimes associated with a hormone disorder known as hyperparathyroidism (Canadian Press, 2014). There is no cure for bipolar disorder, but drug therapy does help many people.

Anti-anxiety Medications

Antianxiety medications are drugs that help relieve fear or anxiety. They work by increasing the action of the neurotransmitter GABA. The increased level of GABA helps inhibit the action of the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system, creating a calming experience.

The most common class of antianxiety medications is the tranquilizers, known as benzodiazepines. These drugs, which are prescribed millions of times a year, include Ativan, Valium, and Xanax. The benzodiazepines act within a few minutes to treat mild anxiety disorders but also have major side effects. They are addictive, frequently leading to tolerance, and they can cause drowsiness, dizziness, and unpleasant withdrawal symptoms including relapses into increased anxiety (Otto et al., 1993). Furthermore, because the effects of the benzodiazepines are very similar to those of alcohol, they are very dangerous when combined with it.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy

Psychedelic-assisted therapy is emerging as a promising treatment option for various mental health disorders, notably treatment-resistant depression and PTSD. Conducted under stringent clinical supervision, this innovative therapeutic approach integrates the controlled use of psychedelic substances like psilocybin and MDMA into psychotherapy sessions, designed to facilitate profound psychological insights and emotional processing.

Recent research highlights the effectiveness of these therapies. Significant reductions in depression symptoms have been documented following psilocybin-assisted therapy, with sustained effects over time [Davis et al., 2020]. Psilocybin activates serotonin receptors in the brain, which appears to “reset” neural circuits that contribute to depressive symptoms. Similarly, MDMA has shown promise in facilitating emotional breakthroughs in PTSD treatment by enhancing neurotransmitter activity — serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine — that elevates mood and diminishes the fear response, allowing patients to engage more effectively with therapeutic interventions [Mitchell et al., 2021].

The safety of psychedelic therapy is well-documented in clinical research, with a noted low abuse potential and absence of overdose fatalities [Johnson et al., 2017]. Common side effects are generally transient and include nausea and headaches, manageable within a clinical setting. Strict adherence to therapeutic dosing and protocols reduces MDMA’s neurocognitive effects [Jerome et al., 2020].

Given the potent nature of psychedelic substances, regulatory guidelines are rigorous. Treatment is restricted to controlled environments with professional oversight to ensure patient safety and maximise therapeutic outcomes [Feduccia et al., 2018].

As research progresses and regulatory frameworks evolve, psychedelic-assisted therapy may offer a viable alternative to conventional treatments, particularly for patients who have not responded to traditional therapy modalities. This approach represents a significant paradigm shift in the treatment of mental health disorders, combining established psychotherapeutic techniques with the therapeutic potential of psychedelic substances.

Direct Brain Intervention Therapies

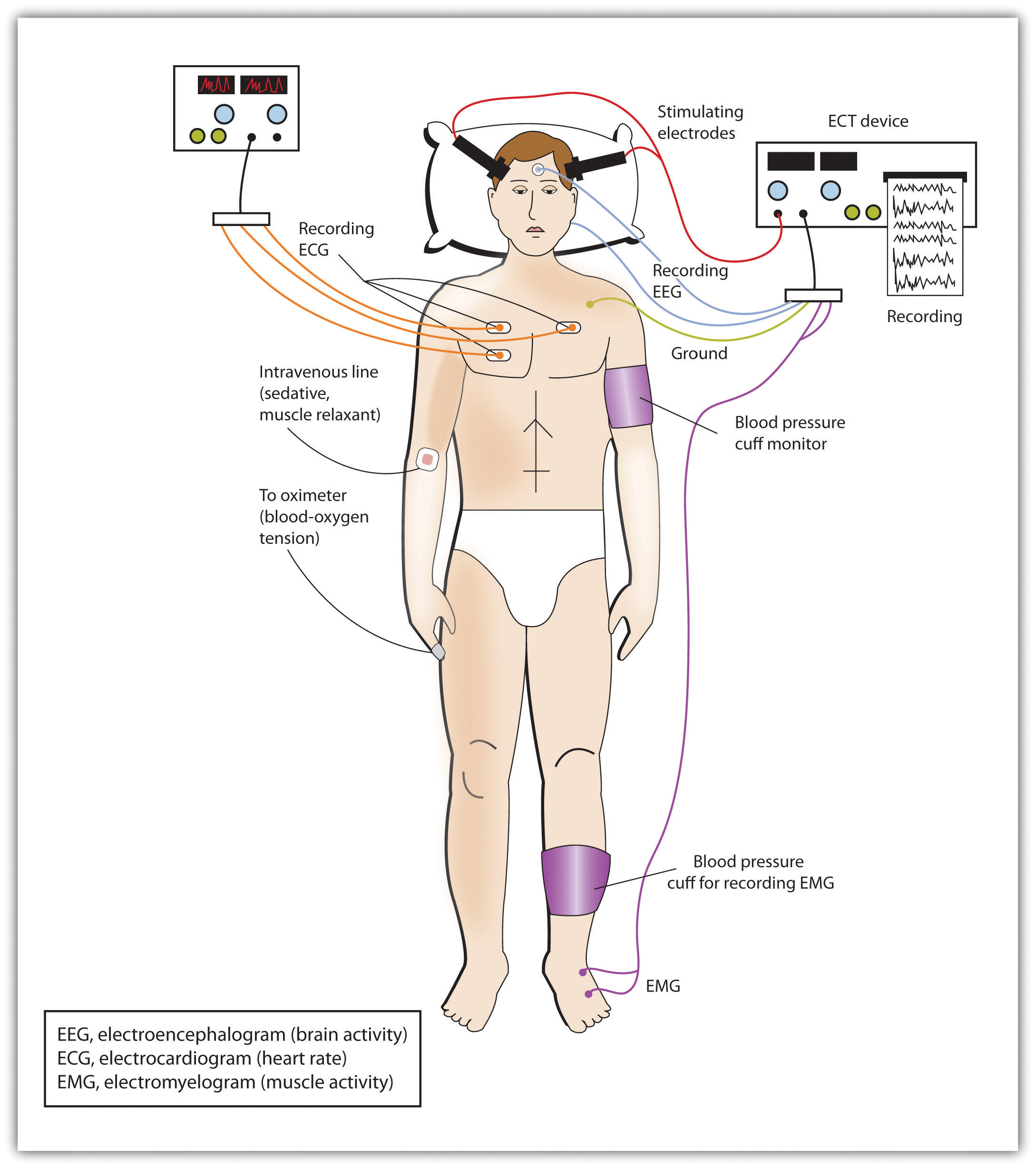

In cases of severe disorder it may be desirable to directly influence brain activity through electrical activation of the brain or through brain surgery. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a medical procedure designed to alleviate psychological disorder in which electric currents are passed through the brain, deliberately triggering a brief seizure (Figure PY.10). ECT has been used since the 1930s to treat severe depression.

When it was first developed, the procedure involved strapping the patient to a table before the electricity was administered. The patient was knocked out by the shock, went into severe convulsions, and awoke later, usually without any memory of what had happened. Today ECT is used only in the most severe cases when all other treatments have failed, and the practice is more humane. The patient is first given muscle relaxants and a general anaesthesia, and precisely calculated electrical currents are used to achieve the most benefit with the fewest possible risks.

ECT is very effective; about 80% of people who undergo three sessions of ECT report dramatic relief from their depression. ECT reduces suicidal thoughts and is assumed to have prevented many suicides (Kellner et al., 2005). On the other hand, the positive effects of ECT do not always last; over one-half of patients who undergo ECT experience relapse within one year, although antidepressant medication can help reduce this outcome (Sackheim et al., 2001). ECT may also cause short-term memory loss or cognitive impairment (Abrams, 1997; Sackheim et al., 2007).

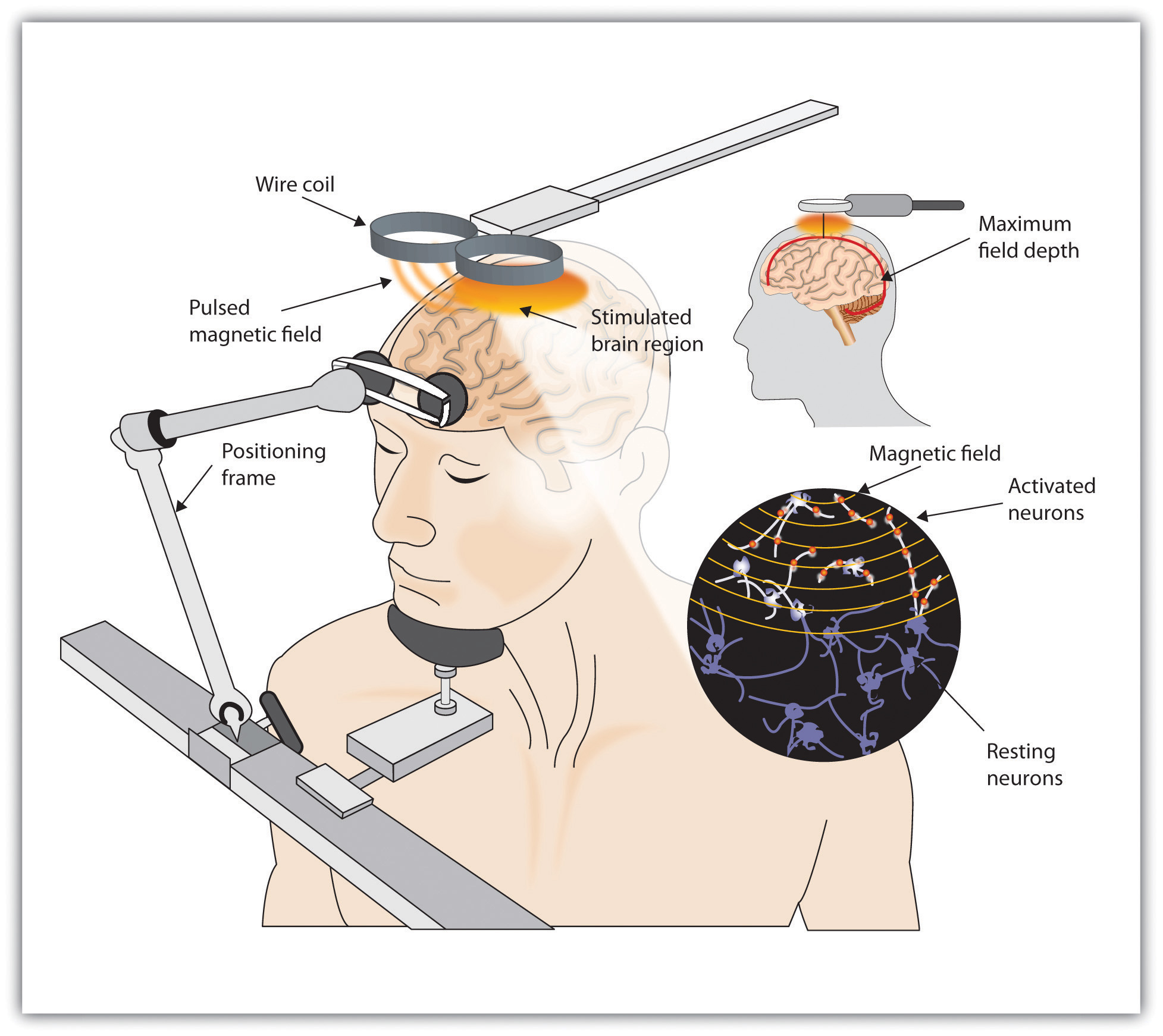

Although ECT continues to be used, newer approaches to treating chronic depression are also being developed. A newer and gentler method of brain stimulation is transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a medical procedure designed to reduce psychological disorder that uses a pulsing magnetic coil to electrically stimulate the brain (Figure PY.11). TMS seems to work by activating neural circuits in the prefrontal cortex, which is less active in people with depression, causing an elevation of mood. TMS can be performed without sedation, does not cause seizures or memory loss, and may be as effective as ECT (Loo, Schweitzer, & Pratt, 2006; Rado, Dowd, & Janicak, 2008). TMS has also been used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia.

Still other biomedical therapies are being developed for people with severe depression that persists over years. One approach involves implanting a device in the chest that stimulates the vagus nerve, a major nerve that descends from the brain stem toward the heart (Corcoran, Thomas, Phillips, & O’Keane, 2006; Nemeroff et al., 2006). When the vagus nerve is stimulated by the device, it activates brain structures that are less active in severely depressed people.

Psychosurgery, that is, surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue in the hope of improving disorder, is reserved for the most severe cases. The most well-known psychosurgery is the prefrontal lobotomy. Developed in 1935 by Nobel Prize winner Egas Moniz to treat severe phobias and anxiety, the procedure destroys the connections between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of the brain. Lobotomies were performed on thousands of patients. The procedure, which was never validated scientifically, left many patients in worse condition than before, subjecting the already suffering patients and their families to further heartbreak (Valenstein, 1986). Perhaps the most notable failure was the lobotomy performed on Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of US President John F. Kennedy, which left her severely incapacitated.

There are very few centres that still conduct psychosurgery today and, when such surgeries are performed, they are much more limited in nature and called cingulotomy (Dougherty et al., 2002). The ability to more accurately image and localise brain structures using modern neuroimaging techniques suggests that new, more accurate, and more beneficial developments in psychosurgery may soon be available (Sachdev & Chen, 2009).

Summary: Mental Health Treatment – Evolution and Contemporary Practices

Historical Perspective and Evolution Historically, mental health issues were often misunderstood, with early beliefs attributing strange behaviour or psychological disorders to demonic possession. Such misconceptions led to harsh treatments including exorcisms, imprisonment, and even execution. The advent of asylums in the 18th century provided a place for those with mental illnesses, though conditions were generally poor and treatments harsh.

In the late 1700s, figures like Philippe Pinel and Dorothea Dix championed more humane treatment for the mentally ill, advocating for reforms that eventually led to better care practices. The mid-20th century saw significant changes with the deinstitutionalisation movement, led by developments in psychiatric medications and a push towards community-based care. However, this shift also led to challenges, such as increased rates of homelessness among the mentally ill due to insufficient community support systems.

Contemporary Approaches to Mental Health Treatment Today, mental health care has evolved to encompass a variety of treatment modalities, focusing on both inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals for severe cases and extensive outpatient services for less severe cases. Modern treatments include psychotherapy, biomedical therapy, and integrative approaches tailored to individual needs. Psychotherapy now includes diverse approaches like cognitive-behavioural therapy, humanistic therapy, and psychodynamic therapy. Biomedical treatments involve medications and procedures like electroconvulsive therapy, with newer modalities like transcranial magnetic stimulation becoming more common.

Treatment settings have expanded beyond traditional therapy offices to include online and app-based platforms, enhancing accessibility. For example, apps like Tranquility provide support for anxiety and depression, reflecting the growing trend of digital mental health solutions.

Biomedical Therapies and Drug Treatments Biomedical therapies are crucial for conditions where psychological distress is linked to neurological imbalances. Common treatments include the use of psychostimulants for ADHD, antidepressants like SSRIs for depression and anxiety, mood stabilisers like lithium for bipolar disorder, and antipsychotics for schizophrenia. These medications adjust neurotransmitter levels in the brain, helping to alleviate symptoms. However, they come with potential side effects and typically need to be carefully managed under medical supervision.

Innovative Therapies and Future Directions Emerging therapies such as psychedelic-assisted therapy show promise, especially for treatment-resistant depression and PTSD. Techniques like electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation offer alternatives for severe cases where traditional medications may not be effective.

Treatment Modalities In individual therapy, a client and therapist work one-on-one to address personal issues. Group therapy gathers 5–10 individuals to discuss a common problem like substance abuse or grief, led by a trained therapist. Couples therapy assists two partners in an intimate relationship to resolve conflicts and strengthen their relationship, regardless of their marital status. Family therapy, a variant of group therapy, involves multiple family members aiming to improve individual and collective family dynamics.

Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders: A Special Case Addiction is considered a chronic disease that changes brain function, leading to high relapse rates of 40%-60%. Treatment focuses on stopping compulsive drug-seeking behaviours and often includes behavioural therapy, which can be conducted individually or in groups, and may be supplemented with medication. Effective treatment frequently addresses comorbid (co-occuring) conditions, such as concurrent mental health disorders, to enhance recovery outcomes.

Inclusive Therapy Models: Sociocultural, Feminist, and Anti-Oppression Approaches

The sociocultural model integrates an individual’s cultural and religious background into therapy, significantly influencing outcomes by enhancing cultural competency. Feminist and anti-oppression therapies extend this by addressing power dynamics and inequalities related to gender, race, and socioeconomic status. These approaches validate clients’ experiences and promote equity within the therapeutic relationship, aiming to dismantle systemic barriers and improve accessibility and satisfaction in mental health services for marginalised groups.

Integrative and Eclectic Approaches Eclectic therapy, which integrates various therapeutic methods and techniques, is becoming increasingly popular for treating complex mental health issues. This approach allows therapists to tailor treatment strategies to individual patient needs, combining elements of behavioural, cognitive, and psychodynamic therapies.

Conclusion The landscape of mental health treatment continues to evolve, with ongoing improvements in the understanding and approaches to therapy. By integrating traditional and innovative methods, mental health professionals aim to provide more effective, personalised care that addresses both the symptoms and underlying causes of mental health conditions.

Image Attributions

Figure PY.10. Figure 15.17 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.11. Figure 15.18 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).