Chapter 6. States of Consciousness

Biological Rhythms

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 13 minutes

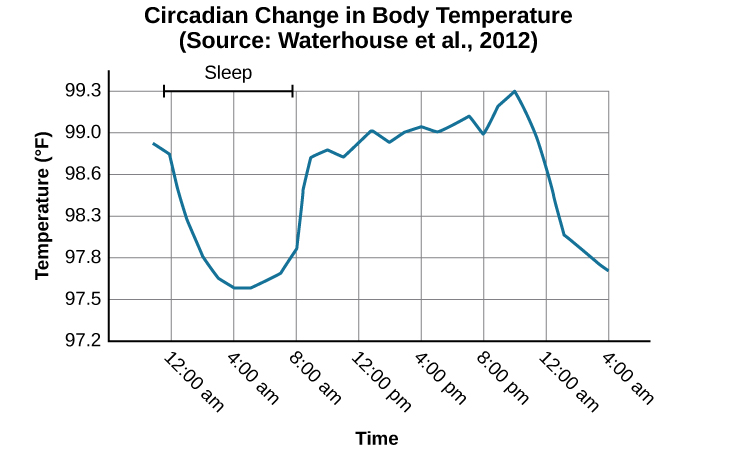

Biological rhythms are internal rhythms of activity that occur within the body. The menstrual cycle is an example of a biological rhythm — a recurring, cyclical pattern of bodily changes. One complete menstrual cycle takes about 29 days — approximately the same length as a lunar month — but many biological cycles are much shorter. For example, body temperature fluctuates cyclically over a 24-hour period (Figure SC.5). Higher body temperatures are often associated with increased alertness, while lower body temperatures can be linked to increased sleepiness (Lack, Gradisar, van Someren, Wright, & Lushington, 2008; Mavjee, & Horne,1994)

The average menstrual cycle length is often cited as 28 days, but recent studies suggest that this is a simplification. The average cycle length can actually be closer to 29 days for many women. Cycle lengths can vary significantly among individuals, typically ranging from 21 to 35 days in adults and from 21 to 45 days in young teens (Office on Women’s Health, n.d.).

The average length of a lunar cycle, also known as a lunar month, is approximately 29.5 days. This is the time it takes for the Moon to complete one orbit around Earth and pass through all of its phases (new moon, first quarter, full moon, and last quarter) (NASA, n.d.).

This daily pattern of temperature changes is a classic example of a circadian rhythm. A circadian rhythm is a natural cycle that lasts about 24 hours, influencing not just our sleep-wake pattern, which aligns with the day-night cycle, but also our heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, and body temperature. These rhythms are crucial to regulating changes in our consciousness.

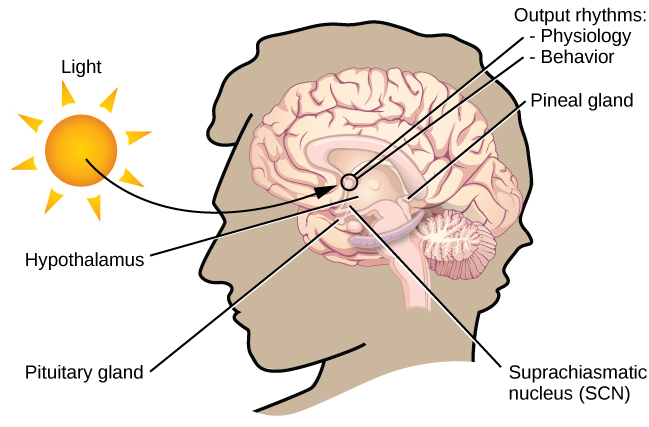

So, do we have a biological clock? In the brain, the hypothalamus, situated above the pituitary gland, plays a key role in maintaining homeostasis — keeping things balanced within our body.

Within the hypothalamus, there’s a specific area called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). This is our brain’s clock. It gets information from light-sensitive neurons in the retina about the amount of light around us, helping this internal clock stay in sync with the external environment (Kiessling, Sollars, & Pickard, 2014; Klein, Moore, & Reppert, 1991; Meijer, Michel, & Vansteensel, 2007; McGlashan, Poudel, Vidafar, Drummond, & Cain, 2018; Welsh, Takahashi, & Kay, 2010).

When our eyes are exposed to light, the retina sends signals to the SCN, which then tells the pineal gland to reduce its melatonin production. Melatonin is a hormone that makes us feel sleepy. As it gets darker in the evening, the SCN’s stimulation decreases, leading to more melatonin being released, making us feel drowsy and relaxed.

Melatonin supplements have been found to effectively reduce the time it takes to go to sleep, and improve sleep quality across various age groups, including children with autism spectrum disorders (Auld et al., 2017; Bueno et al., 2021). Additionally, melatonin plays a significant role in regulating circadian rhythms and sleep quality, potentially beneficial for sleep disturbances related to aging and COVID-19 (Poza et al., 2018; Wichniak et al., 2021).

Watch this video: Reprogramming Our Circadian Rhythms for the Modern World (3.5 minutes)

“Reprogramming Our Circadian Rhythms for the Modern World” video by Big Think is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Disruptions of Normal Biorhythms

Whether you’re an early bird, a night owl, or somewhere in between, there are times when your body’s internal clock falls out of sync with the outside world. This often happens when you travel across multiple time zones, leading to jet lag. Jet lag includes symptoms like fatigue, sluggishness, irritability, and insomnia, which means having trouble falling or staying asleep at least three nights a week for a month (Roth, 2007).

Shift Work

People who work rotating shifts also tend to have their circadian rhythms disrupted. This kind of work involves changing work hours frequently, from early to late shifts, on a daily or weekly basis. For instance, someone might work from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Monday, switch to 3:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, and then work 11:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday. Such frequent changes can make it hard to maintain a regular sleep-wake cycle, often leading to sleep issues and signs of depression and anxiety (Hung et al., 2016; Hsieh et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2021). These schedules are common in healthcare and service industries and can result in constant exhaustion and irritability, increasing the likelihood of mistakes at work (Gold et al., 1992; Presser, 1995).

The impact of rotating shift work extends beyond just sleep patterns. It significantly affects personal lives, as seen in a study of middle-aged nurses working rotating shifts (West, Boughton & Byrnes, 2009). Many nurses reported that their irregular work hours negatively impacted their family time. One nurse shared, “If you’ve had a partner who works a regular 9 to 5 job… finding quality time to spend together when you’re not completely exhausted is a challenge I’ve faced.” (West et al., 2009, p. 114).

Insufficient Sleep

When people have difficulty getting sleep due to their work or the demands of day-to-day life, they accumulate a sleep debt. A person with a sleep debt does not get sufficient sleep on a continuing basis. The consequences of sleep debt include decreased levels of alertness and mental efficiency. Interestingly, since the advent of electric light, the amount of sleep that people get has declined. While we certainly welcome the convenience of having the darkness lit up, we also suffer the consequences of reduced amounts of sleep because we are more active during the nighttime hours than our ancestors were. As a result, many of us sleep less than 7-8 hours a night and accrue a sleep debt. While there is tremendous variation in any given individual’s sleep needs, the National Sleep Foundation (n.d.) cites research to estimate that newborns require the most sleep (between 12 and 18 hours a night) and that this amount declines to just 7-9 hours by the time we are adults.

If you lie down to take a nap and fall asleep very easily, chances are you may have sleep debt. Given that college students are notorious for suffering from significant sleep debt (Hicks, Fernandez, & Pelligrini, 2001; Hicks, Johnson, & Pelligrini, 1992; Miller, Shattuck, & Matsangas, 2010), chances are that you and your classmates deal with sleep debt-related issues on a regular basis. In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation updated their sleep duration hours, to better accommodate individual differences. Table SC.1 shows the new recommendations, which describe sleep durations that are “recommended”, “may be appropriate”, and “not recommended”.

| Age | Recommended | May be appropriate | Not recommended |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 months | 14–17 hours | 11–13 hours

18–19 hours |

Fewer than 11 hours

More than 19 hours |

| 4–11 months | 12–15 hours | 10–11 hours

16–18 hours |

Fewer than 10 hours

More than 18 hours |

| 1–2 years | 11–14 hours | 9–10 hours

15–16 hours |

Fewer than 9 hours

More than 16 hours |

| 3–5 years | 10–13 hours | 8–9 hours

14 hours |

Fewer than 8 hours

More than 14 hours |

| 6–13 years | 9–11 hours | 7–8 hours

12 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours

More than 12 hours |

| 14–17 years | 8–10 hours | 7 hours

11 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours

More than 11 hours |

| 18–25 years | 7–9 hours | 6 hours

10–11 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours

More than 11 hours |

| 26–64 years | 7–9 hours | 6 hours

10 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours

More than 10 hours |

| ≥65 years | 7–8 hours | 5–6 hours

9 hours |

Fewer than 5 hours

More than 9 hours |

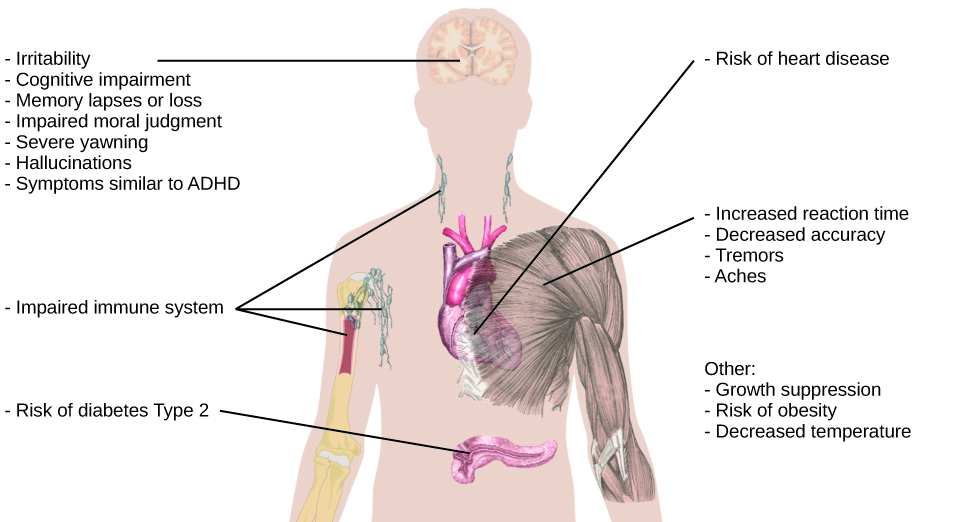

Sleep debt and sleep deprivation have significant negative psychological and physiological consequences (Figure SC.7). As mentioned earlier, lack of sleep can result in decreased mental alertness and cognitive function. In addition, sleep deprivation often results in depression-like symptoms. Sleep deprivation is associated with obesity, increased blood pressure, increased levels of stress hormones, and reduced immune functioning (Banks & Dinges, 2007; De Lorenzo et al., 2018; Kuetting, et al., 2019). These effects can occur as a function of accumulated sleep debt or in response to more acute periods of sleep deprivation.

A sleep-deprived individual generally will fall asleep more quickly than if they were not sleep-deprived. Some sleep-deprived individuals have difficulty staying awake when they stop moving, such as when sitting and watching television or driving a car. That is why individuals suffering from sleep deprivation can put themselves and others at risk if they “drive drowsy” (see Supplement SC.4 for more about drowsy driving) or work with dangerous machinery.

Some research suggests that sleep deprivation affects cognitive and motor function as much as, if not more than, alcohol intoxication (Williamson & Feyer, 2000). Research shows that the most severe effects of sleep deprivation occur when a person stays awake for more than 24 hours (Killgore & Weber, 2014; Killgore et al., 2007), or following repeated nights with fewer than four hours in bed (Wickens, Hutchins, Lauk, Seebook, 2015). For example, irritability, distractibility, and impairments in cognitive and moral judgment can occur with fewer than four hours of sleep. If someone stays awake for 48 consecutive hours, they could start to hallucinate.

To hallucinate means to see, hear, or feel things that aren’t really there. It’s like experiencing a dream while you’re awake. These sensations can seem very real to the person experiencing them, even though they’re created by the mind.

Have you ever stayed awake so long that you started to hallucinate?

Summary

This section delves into the concept of biological rhythms, focusing on how our internal clocks are integral to our well-being and how modern life often disrupts these natural patterns. It begins by exploring the science behind circadian rhythms, which regulate sleep, wakefulness, and numerous physiological processes.

Disruptions of normal biorhythms, such as those caused by jet lag or shift work, are examined, emphasising the impact on physical and mental health. Discussions of strategies for coping with these disruptions provide practical advice for minimising their adverse effects. The section also addresses the widespread issue of insufficient sleep, underscoring the importance of understanding sleep needs at different stages of life and the risks associated with not meeting these needs, including the dangers of drowsy driving.

Image Attributions

Figure SC.5. Figure 4.2 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure SC.6. Figure 4.3 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure SC.7. Figure 4.5 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

- Table adapted from OpenStax Introduction to Psychology 2e. ↵

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).