Chapter 12. Emotion

Biology of Emotions

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 35 minutes

In this section, we delve deeper into the biology of the limbic system, the brain region that governs emotion and memory (Kensinger & Schacter, 2005; Li et al., 2016). Please refer to Figure EM.4 in What are Emotions? for a visual representation. The limbic system comprises the hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus. The hypothalamus is instrumental in activating the sympathetic nervous system, a key player in all emotional responses (Takeda et al., 2009). The thalamus acts as a sensory relay station, with neurons that extend to the amygdala and higher cortical areas for advanced processing (Onoda et al., 2008). The amygdala is pivotal in the processing of emotional information before conveying it onward (Fossati, 2012). Meanwhile, the hippocampus is essential for merging emotional experiences with cognitive functions (Femenía, Gómez-Galán, Lindskog, & Magara, 2012; Wittmann et al., 2008). Functional connectivity within limbic-frontal circuitry is also important during emotion regulation (Banks et al., 2007), and the limbic system’s role in emotional salience modulates processes engaged during accurate retrieval of memories (Kensinger & Schacter, 2005).

The Amygdala: The Brain’s Emotional Communication Centre

The amygdala plays a central role in processing emotions, especially those related to fear and anxiety (LeDoux, 2007). It acts as our brain’s rapid-response alarm system, alerting us to potential threats even before our conscious mind has had a chance to react. For a university student, think of the amygdala as that friend who always jumps to conclusions without getting the full story. For instance, during a surprise quiz, it’s the amygdala that might make your heart race and palms sweat, even if you’ve studied well.

But the amygdala’s responsibilities don’t end with sensing danger. It’s intricately involved in a spectrum of emotions, from the joy of acing an exam to the sorrow of a breakup (Hamann, Ely, Hoffman, & Kilts, 2002). Moreover, this structure is linked to our attention and sensitivity toward emotionally charged events, making us remember them more vividly (Anderson, 2007).

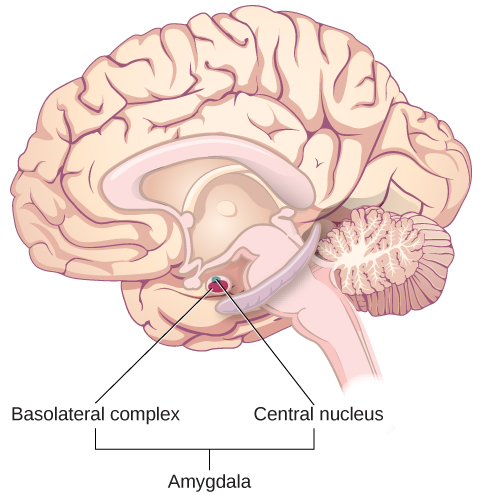

The amygdala has received a lot of of attention from researchers interested in understanding the biological reasons for emotions, especially fear and anxiety (Blackford & Pine, 2012; Goosens & Maren, 2002; Maren, Phan, & Liberzon, 2013). The amygdala is made up of various subnuclei, including the basolateral complex and the central nucleus (Figure EM.10). The basolateral complex has dense connections with a variety of sensory areas of the brain. It is critical for classical conditioning and for attaching emotional value to learning processes and memory. The central nucleus plays a role in attention, and it has connections with the hypothalamus and various brainstem areas to regulate the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems’ activity (Pessoa, 2010).

Our life experiences, especially those in early life, can shape the amygdala’s function. Children who experience neglect or high levels of stress may undergo changes in how their amygdala responds to emotional situations (Dannlowski et al., 2013). Even prenatal experiences, like when a mother undergoes depression during pregnancy, can influence the amygdala’s connectivity in the child, emphasising the profound impact of early environments on our emotional processing (Qiu et al., 2015).

Research also suggests a relationship between the amygdala and psychological disorders of mood or anxiety. Changes in amygdala structure and function have been observed in adolescents who are either at-risk or have been diagnosed with various mood and/or anxiety disorders (Miguel-Hidalgo, 2013; Qin et al., 2013). It has also been suggested that functional differences in the amygdala could serve as a biomarker to differentiate individuals suffering from bipolar disorder from those suffering from major depressive disorder (Fournier, Keener, Almeida, Kronhaus, & Phillips, 2013).

Hippocampus and Emotional Processing

As mentioned earlier, the hippocampus is also involved in emotional processing. Like the amygdala, researchers have discovered that hippocampal structure and function are linked to a variety of mood and anxiety disorders. Individuals suffering from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) show marked reductions in the volume of several parts of the hippocampus, which may result from decreased levels of neurogenesis and dendritic branching (the generation of new neurons and the generation of new dendrites in existing neurons, respectively) (Wang et al., 2010; Kitayama et al., 2005; Levy-Gigi et al., 2015; Woon et al., 2010; van Rooij et al., 2015; Dennis et al., 2019; Irle et al., 2009). While it is impossible to make a causal claim with correlational studies like these, researchers have observed behavioural improvements and hippocampal volume increases following either pharmacological (prescribed drugs) or cognitive-behavioural therapy in individuals suffering from PTSD (Bremner & Vermetten, 2004; Levy-Gigi, Szabó, Kelemen, & Kéri, 2013; Moustafa, 2013).

The “Orchestra” Model of Emotions

More recent research reveals that emotions are not just localized in subcortical areas, challenging several contemporary theories of emotion (Wager et al., 2015). For example, Saarimäki, et al. (2018) studied 14 emotions and found that “all emotions engaged a multitude of brain areas.” To understand this in simpler terms, consider the analogy of a concert orchestra. Traditional theorists might have seen emotions as being played by one specific section of the orchestra (e.g., the strings). However, newer research suggests that the entire orchestra plays a part in producing the “music” of emotions, with different sections contributing at different times.

Watch this video: Feeling All the Feels: Crash Course Psychology #25 (11 minutes)

“Feeling All the Feels: Crash Course Psychology #25” video by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Emotional Geographies

Moving on from the intricate workings of the brain’s emotional centres to the expansive realm of emotional geographies requires us to take another shift in perspective from the internal to the external, from the biological to the environmental. We’ve explored the limbic system’s role in mediating our emotional responses, delving into the amygdala’s function as the brain’s emotional communication centre and the hippocampus’s involvement in emotional processing. This journey through the brain’s emotional orchestra has highlighted the complex interaction between various neural structures in shaping our emotional experiences.

According to emotional geographic theories, emotions are not solely individual experiences; they are also shaped by societal, spatial, and environmental contexts (Smith, Davidson, Cameron, & Bondi, 2009). The field of emotional geographies emphasises the interaction between emotions and the places we inhabit, the times we live through, the people we encounter, and the events we have experienced (Anderson & Smith, 2001). Recognising that some emotions are anchored outside ourselves and that some external stimuli can trigger our emotional responses allows us to begin to comprehend what Indigenous scholars mean when they assert that the Land offers lessons to us and can not only speak to us but also teach us about ourselves.

Let’s begin with a clarification. Even though the following concepts all come under the category of emotional geographies, there is far more to this concept than place-based experiences. In this case, the term “geography” is being used to describe “that which is external to ourselves.” Here is a list of some of the emotional geographies you may encounter or already have encountered.

- Emotion and Place Interaction: Emotions are deeply influenced by the external world, particularly the places we frequent (Davidson, Bondi, & Smith, 2005). The profound connection between emotions and places has been well-documented, with certain locations evoking specific emotions based on past experiences or cultural narratives.

- Social and Cultural Dimensions: Emotional geographies, rooted in feminist theory, emphasise that emotions are not just individual experiences but are shaped by cultural, social, and historical contexts (Bondi, 2005). Different cultures and societies understand, express, and experience emotions in relation to places differently.

- Embodied Emotions: Our bodies are the primary vessels through which we experience emotions. The physical sensations we feel in various places in our bodies (like our cranky, creaky back) play a crucial role in our emotional experiences (Davidson & Milligan, 2004).

- Emotions in Everyday Spaces and Objects: Everyday spaces, like our homes or local grocery stores, and sentimental objects play a pivotal role in our emotional well-being (Duff, 2010). These spaces and objects, often overlooked, are reservoirs of memories, experiences, and feelings.

- Emotions evoked by music and other media: Music and songs are often seen as emotional geographies because they can evoke, represent, and even shape the emotional landscapes of individuals and communities. Songs and shows can powerfully evoke sentimental emotions (Brown, 2016)

- Power Dynamics and Feminist Theory in Emotional Geographies: Feminist theory has played a significant role in shaping the discussion around emotional geographies, particularly in understanding how societal power dynamics influence our emotional experiences in spaces (Longhurst, 2005). Factors like gender, race, class, and sexuality play a significant role in shaping these perceptions. For example, see Black feminist perspectives.

- Black feminist or womanist perspective on emotions focuses on how our feelings are shaped by the mix of our gender, race, class, and whom we love (Rodgers, 2017). This view points out that our emotions are deeply connected to our community and the people we come from, like our mothers and grandmothers (Applebaum, 2017). It also suggests that the place we live and our environment play a big role in how we feel (González-Hidalgo & Zografos, 2020). This approach understands that the society we live in, especially the unjust parts about race and gender, can change the way we express and experience our emotions (Åhäll, 2018; Kulbaga & Spencer, 2021). By looking at emotions through this lens, we can better understand the emotional lives of Black women and other minoritised groups often left out of the academic consideration (Doharty, 2020). This gives us a fuller, more detailed picture of how different people experience and show their feelings.

Emotional geographies offer a holistic perspective on emotions, emphasising their interconnectedness with the external world. As we navigate through various spaces, we carry with us myriad emotions, each shaped by our personal experiences, cultural backgrounds, and societal norms.

Watch this video: Emotional Georgraphies of the Weight Room (8 minutes)

“Emotional Georgraphies of the Weight Room” video by Caitlin DiCara is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Emotional Geographies also Give Us a Beginning Understanding of Indigenous Wisdom about the Land

Extending the concept of emotional geographies into the realm of Indigenous wisdom deepens our understanding of the profound interconnectedness between the human spirit and the Land. Indigenous scholars and elders often speak of the Land not merely as a physical space but as a living, breathing entity that communicates and teaches. This dialogue with the Land reflects a symbiotic relationship where emotions are not solely human experiences but are shared with and influenced by the Land itself. The Land, with its rivers, mountains, forests, deserts, and Living Ones is seen as an ancestral repository holding centuries of wisdom, stories and emotional imprints that are accessible to those who listen deeply and respectfully (Fernández‐Llamazares, & Cabeza, 2018; Hak, Underhill-Sem, & Ngin, 2021; Jacobs, 1994; Konishi, 2015). This concept challenges the dominant scientific perspective that often views emotions as internal, individualistic experiences. For Indigenous Peoples, emotions are a shared language between humans and the Land.

Summary: Biology of Emotions and Emotional Geographies

In this section, we delve into the biology of emotions, exploring how our brains process and experience emotions. We start by examining the amygdala, often referred to as the brain’s emotional communication center, which plays a crucial role in how we perceive and react to emotional stimuli. Next, we look at the hippocampus and its significant role in emotional processing, particularly in forming and retrieving emotional memories.

We also introduce the “orchestra” model of emotions, a metaphor that illustrates how various brain regions work together harmoniously to produce the complex experience of emotions. This model helps us understand that emotions are not the result of isolated brain activities but are the outcome of intricate interactions within our neural networks.

Furthermore, we explore the concept of emotional geographies, which extends our understanding of emotions beyond the biological to the spatial and environmental. Emotional geographies examine how our feelings are influenced by, and interact with, the spaces and places we inhabit. This concept opens up discussions about the connection between emotions and our environment, including how Indigenous wisdom about the land can offer profound insights into our emotional well-being.

Image Attributions

Figure EM.10. Figure 10.23 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).