Chapter 13. Motivation

Blackstock’s and Maslow’s Theories of Needs and Motivations

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 23 minutes

This section contrasts the perspectives of Blackstock’s Breath of Life Theory and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, offering a rich exploration of human needs and motivations from distinct viewpoints. First, we introduce Cindy Blackstock and the Breath of Life Theory, rooted in the interconnectedness and communal well-being emphasised by Indigenous cultures, challenging the traditional hierarchical models of needs. Next, we revisit Maslow’s well-known theory, examining its evolution and the common misinterpretations that have simplified its complexity over time. Finally, we compare these two theories side by side, highlighting their differences in focus, structure, and cultural inclusivity, and what these differences mean for understanding human motivation. This section aims to broaden our perspective on what drives us, acknowledging the diversity of human experience and the importance of cultural context in shaping our motivations.

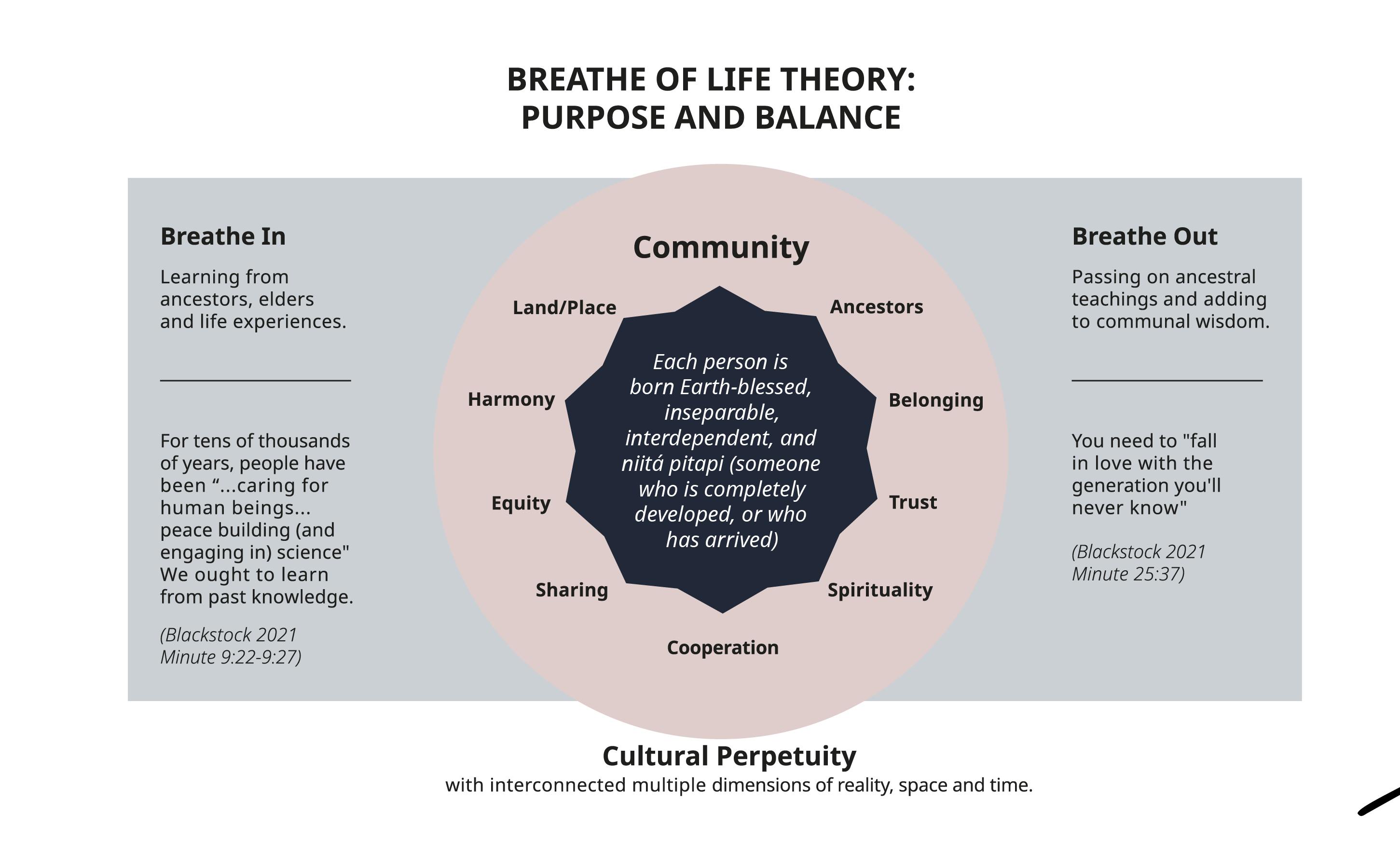

Blackstock’s Breath of Life Theory: Balance as Purpose

Cindy Blackstock, a prominent member of the Gitxsan First Nation, is a celebrated advocate for Indigenous children’s rights in Canada. Her work, deeply rooted in her Indigenous heritage, has significantly guided our understanding of psychology, particularly in understanding human needs and motivations. The Breath of Life Theory both challenges and expands upon traditional European/settler psychological models like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

What is the Breath of Life Theory?: The Four B’s

The Breath of Life Theory calls us to shift our understanding of human needs and motivations. It emphasises a holistic view of human existence, underscoring the interconnectedness of individuals within their communities and with their ancestors. The Breath of Life Theory says that human needs are not hierarchical but are interconnected and equally important throughout life (Blackstock, 2011; 2019; 2021). This perspective aligns with many Indigenous cultures’ views, which often emphasise the importance of community, the interconnectedness of all life forms, and the continuity of knowledge and wisdom across generations.

Seeking balance as our primary motivation

Blackstock teaches us that the overall abiding purpose of our lives is to live in balance. Balance is possible with the ongoing, equitable, “deliberate and thoughtful actions made by people who position their own survival as codependent with the health of other people across generations and with the universe.” Our growth as humans involves always seeking balance in all relationships, while fully realising that we are blessed, always blossoming, held in an interconnected web of belonging, and that our gift back to all is our being of service (Blackstock, 2011; 2019; 2021).

Here is Blackstock’s theory summarised, using words that start with “B”.

The Breath of Life Theory introduces us to four kinds of human needs and motivations that interconnect to shape our lives:

- Blessed. First, it emphasises that we are blessed with the Earth’s abundance, highlighting our inseparable and interdependent relationship with nature.

- Becoming. Second, it teaches us that we are always blossoming, born fully developed, or niita’pitapi, a term meaning “someone who is completely developed, or who has arrived” (cited in Ravilochan, 2021). In Blackfoot culture, “it’s like you’re credentialed at the start. You’re treated with dignity for that reason, but you spend your life living up to that.“ (Ravilochan, 2021).

- Belonging. Third, the theory underscores the importance of belonging — our connections to community, family, land, water, and all living beings — fostering trust, harmony, and cooperation.

- Being of Service. Fourth, it involves seeking a fair balance in all relationships across physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual dimensions, and considering the past, present, and future.

Similar ideas can be seen among other Indigenous groups in North America. For example, Mi’kmaq (First Nations) peoples (Meeg-mah) are the main Indigenous Peoples of Atlantic Canada. Mi’kmaq peoples have an important concept of Netukulimk (Neh-doo-goo-limbk) in their culture. This concept highlights how communities are inseparable from the land and the land’s resources, as they are interconnected and must support one another (Prosper, 2011). In this way, land is a community. This is expressed by the Mi’kmaq saying Msit No’kmaq (mm-sit-no-goh-mah), or “all my relations”, which means that all living things and pieces of the earth are Mi’kmaq relatives (Hurley & Jackson, 2020). Another value involving cultural perpetuity comes from the Haudenosaunee (Hoe-dee-no-show-nee) peoples, also known as Iroquois or the Six Nations, which are a group of Indigenous Peoples living in the United States and Canada. The Haudenosaunee peoples have the Seven Generation Principle, which is similar to that of cultural perpetuity; this principle highlights how important it is for community members to make decisions that will result in a sustainable world for the next seven generations (Mclester, 2017).

Blackstock’s theory, deeply grounded in Indigenous perspectives, underscores the interconnectedness of all life’s aspects, weaving together spiritual, emotional, physical, and cognitive dimensions. She says that one of our primary motivations is meeting human needs. This is a communal endeavour, firmly anchored in ancestral wisdom and the sustainability of future generations. This holistic and communal approach sharply diverges from the model proposed by Maslow, which is next in our discussion. Maslow’s model, in contrast, is characterised by a hierarchical structure that prioritises individual development and fulfilment. It suggests a progression of needs, where higher needs emerge once lower ones are satisfied, focusing primarily on the individual rather than the collective well-being and interconnectedness emphasised by Blackstock.

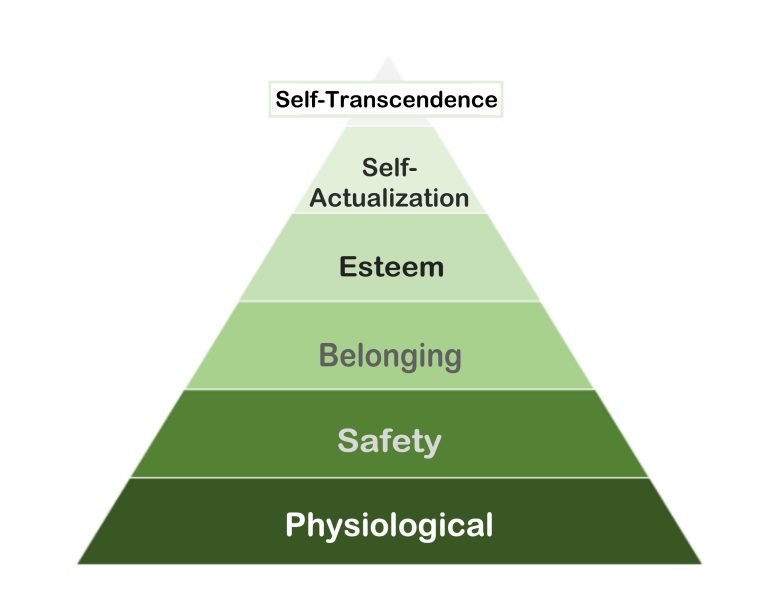

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

In this section we will discover how a renowned psychological theory has been changed and misinterpreted over time. Imagine playing the game of “telephone,” where a message gets distorted as it is whispered from person to person. This analogy aptly describes the changes and errors introduced into Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, a theory that has been reshaped and misunderstood over time.

“A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if (they) are to be ultimately happy. What a (person) can be, (they) must be. This need we may call self-actualisation. (Maslow, 1943)”

When it was first published, Maslow’s theory did not make a significant impact in the psychological community. However, it caught the attention of the business management world, where McDermid (1960) oversimplified Maslow’s model for practical use in workplace training. This simplified ‘pyramid’ version, stripped of Maslow’s complexities, became very popular in the business realm and eventually found its way back to psychology, but in a distorted, oversimplified form. For over 70 years, this misrepresentative model has been widely discussed and depicted as a pyramid, with basic needs at the base and advanced needs at the peak. This image, however, is not what Maslow intended (Maslow, 1943).

Maslow’s original hierarchy, as he proposed in 1943, was more complex. He later expanded it to include cognitive and aesthetic needs and introduced the concept of self-transcendence, the motivation to pursue goals beyond oneself, such as altruism and spirituality (Koltko-Rivera, 2006).

A more accurate visualisation of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs might be a staircase that one can ascend or descend depending on positive or negative life events. Contrary to progressing through our needs in irreversible stages, Maslow theorised that we can ascend the “stairs” of the hierarchy based on the success of personal choices, social and material privileges, personal health history, and various external pressures. When stresses are significant, we may have to move down the stairs. Conversely, when life events are favourable, we move up the stairs of the hierarchy. Our life events deeply affect if and how we self-actualise and at what pace.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (with 1970 updates by Maslow)

- Physiological Needs: These are the basic survival needs such as food, water, and shelter. Example: grabbing a sandwich and a bottle of water to satisfy hunger and thirst.

- Safety Needs: This level includes the need for security and safety. Example: locking your doors at night to feel secure in your home.

- Belongingness and Love Needs: These needs encompass relationships, love, and affection. Example: spending time with friends or family to feel connected and loved.

- Esteem Needs: This level covers the need for self-esteem, respect, and recognition. Example: receiving praise at work for a job well done, which boosts your self-confidence.

- Cognitive Needs: This addition reflects the desire for knowledge and understanding. Example: reading a book or researching a topic online to satisfy your curiosity.

- Aesthetic Needs: This step includes the appreciation of beauty and form. Example: visiting an old growth forest to admire its beauty and experience a sense of awe.

- Self-Actualisation: This is the need to realise one’s full potential and abilities. Example: pursuing a lifelong dream, like travelling the world or starting a business, to fulfil your personal goals.

- Self-Transcendence: This final step, added later, involves the pursuit of goals beyond the self, like altruism and spirituality. Example: volunteering at a local shelter, finding fulfilment in helping others, and contributing to a greater cause.

An important aspect that is often overlooked in discussions about Maslow’s work is his failure to acknowledge the influence of the Blackfoot nation, who hosted him and likely contributed to his understanding of self-actualisation and community-focused values. This omission highlights a broader issue in the field of psychology, where Indigenous and non-European/Settler contributions are often underrepresented or unrecognised.

Understanding the evolution of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs offers a valuable lesson in how theories can be changed and misinterpreted over time. It also underscores the importance of cultural context in psychological theories and the need to recognise and integrate diverse perspectives and give credit where credit is due.

If you want to read more about the process of rediscovering Blackfoot science and their influence on Maslow, read this article published by the Government of Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council: Rediscovering Blackfoot Science: How First Nations Helped Develop a Keystone of Modern Psychology.

Critics have pointed out that Maslow’s theory, despite its revisions, is heavily influenced by European/Settler values and may not accurately reflect the needs and motivations of people from different cultural backgrounds (Bouzenita & Boulanouar, 2016; Zhang, 2017; Gambrel & Cianci, 2003). This ethnocentric bias, when someone thinks their own culture or group is better or more important than others, is a significant limitation that overlooks the diverse ways in which different cultures understand and prioritise human needs.

Watch this video: Sailing Towards Transcendence | Scott Barry Kaufman (5.5 minutes)

“Sailing Towards Transcendence | Scott Barry Kaufman” video by APB Speakers is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Blackstock’s Compared to Maslow’s Theories

The following comparison of the Breath of Life Theory with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see Table MO.6) shows that they differ in several key ways:

| Perpective | Blackstock | Maslow |

|---|---|---|

| Individual versus Communal Focus | Includes communal well-being and interconnectedness of individuals within their community and with their ancestors (Blackstock, 2007). | Primarily focuses on individual development and fulfilment (Maslow, 1970). |

| Hierarchy versus Holism | Views needs as inherently interconnected and equally important throughout life, without a hierarchical structure (Blackstock, 2007). | Suggests a progression of needs, where higher needs emerge once lower ones are satisfied (Maslow, 1943). |

| Cultural Context and Inclusivity | Offers a more culturally inclusive and contextually rich perspective (Blackstock, 2007). | Primarily rooted in Western values, and may not fully encompass the cultural dimensions of motivation and needs present in Indigenous cultures (Maslow, 1970). |

| Concept of Self-Actualisation | Redefines self-actualisation as an inherent trait present in everyone from birth, emphasising the role of community and cultural perpetuity in personal development (Blackstock, 2007). | Self-actualisation is seen as the pinnacle of personal development, achieved after satisfying other lower-level needs (Maslow, 1970). |

Our comparison of these two theories shows that Blackstock’s principles prioritise interconnectedness and well-being, and take a holistic view of human needs. Maslow’s principles centre on the individual, are hierarchical, and focus on becoming one’s best self and giving back to younger generations.

Kaufman’s Sailboat Metaphor for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Scott Barry Kaufman (2021) moves away from Maslow’s pyramid to introduce the sailboat metaphor as a fresh perspective on our needs. In this metaphor, life’s journey is likened to sailing. The boat represents our basic needs for safety and security, while the sail, capturing the wind, symbolises our drive for personal growth, including exploration, love, and purpose. At the highest level, transcendence is envisioned as a seabird soaring above, symbolising goals beyond oneself like altruism and spirituality. This model, updated with Maslow’s 1970 enhancements and McFarlane’s (2024) addition of grit and resilience represented by the sailboat’s mast, emphasises the dynamic nature of our needs and growth.

Unlike the static pyramid, the sailboat suggests that navigating life involves balancing foundational security with the pursuit of growth and transcendence, adapting to the challenges we encounter.

Summary: Blackstock’s and Maslow’s Theories of Needs and Motivations

Blackfoot’s Breath of Life Theory provides a culturally rich and holistic perspective on human needs and motivations. It challenges the traditional European/Settler-biassed psychological models and encourages a more inclusive, communal, and interconnected understanding of human psychology. Maslow’s theory and the Breath of Life theory differ fundamentally in their approaches to human needs and motivation. While Maslow’s revised hierarchy focuses on individual development, the Breath of Life theory emphasises communal well-being and interconnectedness. Maslow suggests a progression of needs, whereas the Breath of Life theory views needs as inherently interconnected and equally important throughout life, and says that one theory is not necessarily better than the other. Both theories can teach us about our human needs and sources of motivation.

Image Descriptions

Figure MO.12. Breath of Life theory image description:

Title: Breathe of Life Theory: Purpose and Balance.

Cultural Perpetuity: With interconnected multiple dimensions of reality, space, and time.

- Community: Each person is born Earth-blessed, inseparable, interdependent, and niitá’pitapi (someone who is completely developed, or who has arrived).

- Ancestors

- Belonging

- Trust

- Spirituality

- Cooperation

- Sharing

- Equity

- Harmony

- Land/Place

- Breathe in: Learning from ancestors, elders and life experiences. Quote: For tens of thousands of years, people have been “… caring for human beings… peace building (and engaging in) science”. We ought to learn from past knowledge. (Blackstock 2021, Minute 9:22-9:27).

- Breathe out: Passing on ancestral teachings and adding communal wisdom. Quote: You need to “fall in love with the generation you’ll never know”. (Blackstock 2021, Minute 25:37). [Return Figure MO.12]

Image Attributions

Figure MO.12. Breath of Life theory by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure MO.13. Figure EM.8 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure MO.14. Credit: Glenbow Archives. Public domain image.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).