Chapter 14. Personality

Cognitive-Behaviourist Perspectives on Personality

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 15 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Contrast Skinner’s and Bandura’s approaches to understanding personality

- Recognise the key concepts in Bandura’s, Rotter’s, and Mischel’s theories

In contrast to the Freudians and neo-Freudians, who relate personality to inner and hidden processes, the learning approaches discussed in this section focus only on observable behaviour. This illustrates a significant advantage of the learning approaches over psychodynamics. Because learning approaches involve observable and measurable phenomena, they can be scientifically tested.

Behaviourists do not believe in biological determinism; they do not see personality as inborn. Instead, they view personality as significantly shaped by the reinforcements and consequences outside of the organism. In other words, people behave in a consistent manner based on prior learning. B. F. Skinner, a radical behaviourist, believed that the environment was solely responsible for all behaviour, including the enduring, consistent behaviour patterns studied by personality theorists.

As you may recall from your study on the psychology of learning, Skinner proposed that we demonstrate consistent behaviour patterns because we have developed certain response tendencies (Skinner, 1953). In other words, we learn to behave in particular ways. We increase the behaviours that lead to positive consequences, and we decrease the behaviours that lead to negative consequences. Skinner disagreed with Freud’s idea that personality is fixed in childhood. According to Skinner, personality develops over our entire life, not only in the first few years. Our responses can change as we come across new situations; therefore, we can expect more variability over time in personality than Freud would anticipate. For example, consider a young woman, Greta, a risk taker. She drives fast and participates in dangerous sports such as hang gliding and kiteboarding, but after she has children, the system of reinforcements and punishments in her environment changes. Speeding and extreme sports are no longer reinforced, so she no longer engages in those behaviours. In fact, Greta now describes herself as a cautious person.

Albert Bandura and Reciprocal Determinism

Albert Bandura agreed with Skinner that personality developed through learning. He disagreed, however, with Skinner’s radical behaviourist approach to personality development because he felt that how we interpret a situational event is more important than the event itself. He presented a social-cognitive theory of personality that emphasises both learning and cognition as sources of individual differences in personality. In social-cognitive theory, the concepts of reciprocal determinism, observational learning, and self-efficacy all play a part in personality development.

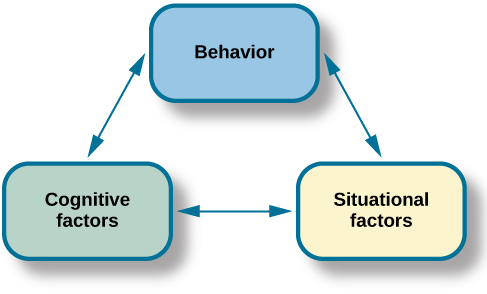

In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behaviour, Bandura (1986) proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behaviour, and context all interact, each factor influencing and being influenced by the others simultaneously. Cognitive factors refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations, and personality characteristics. Behaviour refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behaviour occurs refers to the environment or situational factors, which includes rewarding and punishing stimuli. Consider, for example, that you’re at a festival, and one of the attractions is bungee jumping from a bridge. Do you do it? Your answer may depend on behaviour — your past and current learning experiences with bungee jumping, situation — whether there are rewards for going, such as peer approval, and cognition — your beliefs about whether you will get rewarded for going and how well you can bungee jump. According to reciprocal determinism, all of these factors are in play.

Bandura’s key contribution was the idea that learning could be vicarious. We learn by observing someone else’s behaviour and its consequences, which Bandura called observational learning. He felt that this type of learning also plays a part in the development of our personality. Just as we learn individual behaviours, we learn new behaviour patterns when we see them performed by other people or models. Drawing on the behaviourists’ ideas about reinforcement, Bandura suggested that whether we choose to replicate a model’s behaviour depends on whether we see the model reinforced or punished. Through observational learning, we come to learn what behaviours are rewarded in our culture, and we also learn to inhibit socially unacceptable behaviours by seeing what behaviours are punished.

Self-efficacy is a core cognitive factor that influences learning and personality development (Bandura, 1977, 1995).

Self-efficacy refers to our level of confidence in our own ability to fulfill a task, developed through our social experiences. Self-efficacy affects how we approach challenges and reach goals. People who have high self-efficacy believe that their goals are within reach, maintain a positive view of challenges by seeing them as tasks to be mastered, develop a deep interest in and strong commitment to the activities in which they are involved, and quickly recover from setbacks. Conversely, people with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks because they doubt their ability to be successful, tend to focus on failure and negative outcomes, and lose confidence in their abilities if they experience setbacks. Feelings of self-efficacy are specific to certain situations. For instance, a student might feel confident in their ability in English class but much less so in math class, or vice versa.

Julian Rotter and Locus of Control

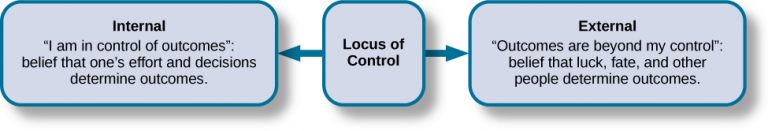

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control. Those of us with an internal locus of control tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control and are instead controlled by other people, luck, or chance. For example, say you didn’t spend much time studying for your psychology test and went out to dinner with friends instead. When you receive your test score, you see that you earned a D. If you possess an internal locus of control, you will most likely admit that you failed because you didn’t spend enough time studying and decide to study more for the next test. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you may conclude that the test was too hard and not bother studying for the next test because you figure you will fail it anyway. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically and are better able to cope with stress than people who have an external locus of control (Benassi et al., 1988; Lefcourt et al., 1981; Whyte, 1977, 1978). You may take the locus of control test.

Walter Mischel and Self-Control

Walter Mischel (1930–2018) argued that understanding personality ought to be understood in the context of situations in which it is used. According to Mischel, it’s not really your personality that stays the same, but rather the way you act in similar situations that tends to happen over and over again (Mischel, 1968). If we look closely at people’s behaviour across many different situations, the consistency is really not that impressive. For example, children who cheat on tests at school may steadfastly follow all rules when playing games and may never tell a lie to their parents. Mischel thought that personality psychologists should focus on people’s unique reactions to specific situations. For example, some kids might be more likely to cheat on a test when the chances of getting caught are low and the rewards for cheating are high. On the other hand, some kids might be drawn to the excitement of taking a risk, even if the rewards aren’t that great. So, a child’s actions are influenced by how they see the risks and rewards in that moment, as well as their own abilities and values. This is why the same child might act very differently in different situations. Mischel thought that specific behaviours are shaped by the interaction between the unique features of a situation, how a person perceives it, and their abilities to handle it. Mischel argued that these social-cognitive processes are what make people react consistently when the situations are similar.

Among Mischel’s most notable contributions were his ideas on self-control. Self-control refers to the ability to control your impulses, emotions and behaviours in order to achieve long-term goals. When we talk about self-control, we tend to think of it as the ability to delay gratification. Would you be able to resist getting a small reward now in order to get a larger reward later? This is the question Mischel investigated in his marshmallow test.

In the marshmallow study, Mischel and colleagues (1972) placed a preschool child in a room with one marshmallow on the table. The child was told that they could either eat the marshmallow now or wait until the researcher returned to the room, and then they could have two marshmallows. This was repeated with hundreds of preschoolers. What the researchers found was that young children differed in their degree of self-control. Mischel and colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and what do you think they discovered? The children who had more self-control in preschool — that is, the ones who waited for the bigger reward — were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores, had positive peer relationships, and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable marriages (Mischel et al., 1989, 2011).

A more recent study using a larger and more representative sample found associations between early delay of gratification (Watts et al., 2018) and measures of achievement in adolescence. However, researchers also found that the associations were not as strong as those reported during Mischel’s initial experiment and were quite sensitive to situational factors such as early measures of cognitive capacity, family background, and home environment. This research suggests that consideration of situational factors is important to better understand personality.

In the years after the publication of Mischel’s (1968) book, debates raged about whether personality truly exists, and if so, how it should be studied. It is certainly true, as Mischel pointed out, that a person’s behaviour in one specific situation is not a good guide to how that person will behave in a very different specific situation. Someone who is talkative at a party may be quiet in class. However, this doesn’t mean that personality isn’t real, and it doesn’t mean that people’s behaviour is completely determined by situations. Personality traits can give an idea of how someone usually acts, but they might not be great at telling us exactly how a person will act in a specific moment. So, to understand traits better, we have to look at behaviours over time and in many different situations. In the next section, we’ll talk about trait theories that try to explain the lasting qualities that influence how people act in lots of different situations.

Image Attributions

Figure PE.7. Figure P.11 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PE.8. Figure P.12 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).