Chapter 3. Psychological Science

Conducting Ethical Research

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 11 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss how research involving human subjects is regulated

- Summarise the processes of informed consent and debriefing

- Explain how research involving animal subjects is regulated

Research Involving Humans

Any experiment involving the participation of human subjects is governed by extensive, strict guidelines designed to ensure that the experiment does not result in harm. In Canada, there are two bodies that provide guidelines for ethical human research that must be adhered to. The Canadian Psychological Association has a code of ethics that members must follow (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). The Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 (TCPS 2) is the most recent set of guidelines for ethical standards in research adhered to by those doing research with human subjects (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 2022). The TCPS 2 is based on three core principles: respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice. Details on these core principles are found in TCP2 Article 1.1.

Any research institution that receives federal support for research involving human participants must have access to an institutional review board (IRB). The IRB is a committee of individuals often made up of members of the institution’s administration, scientists, and community members. The purpose of the IRB is to review proposals for research that involves human participants. The IRB reviews these proposals with the principles mentioned above in mind, and generally, approval from the IRB is required in order for the experiment to proceed.

An institution’s IRB requires several components in any experiment it approves. For one, each participant must provide an informed consent before they can participate in the experiment. In cases where research participants are under the age of 18, the parents or legal guardians are required to sign the informed consent form. An informed consent form contains a written description of what participants can expect during the experiment, like potential risks and implications of the research. It also lets participants know that their involvement is completely voluntary and can be discontinued without penalty at any time. Students in psychology classes may be allowed, or even required, to participate in research, but they are also always given an option to perform other activities instead. Additionally, once an experiment begins, the research participant is always free to leave the experiment if they wish. Concerns with free choice also occur in institutional settings such as schools, hospitals, corporations and prisons, when individuals are required by the institutions to take certain tests or when employees are told to participate in research.

Furthermore, the informed consent guarantees that any data collected in the experiment will remain completely confidential. In some cases, data can be kept anonymous by not having the respondents put any identifying information on their questionnaires. In other cases, the data cannot be anonymous because the researcher needs to keep track of which respondent contributed the data. In this case, one technique is to have each participant use a unique code number to identify their data, such as the last four digits of the student ID number. In this way, the researcher can keep track of which person completed which questionnaire, but no one will be able to connect the data with the individual who contributed them.

While the informed consent form should be as honest as possible in describing exactly what participants will be doing, sometimes deception is necessary to prevent participants’ knowledge of the exact research question from influencing the results of the study. Deception involves purposely misleading experiment participants in order to maintain the integrity of the experiment, but not to the point where the deception could be considered harmful. For example, if we are interested in how our opinion of someone is affected by their attire, we might use deception in describing the experiment to prevent that knowledge from affecting participants’ responses. Researchers must balance the use of deception, like not disclosing the true purpose of the study, with potential harm to the participants. The use of deception must be justified. In cases where deception is involved, participants must receive a full debriefing upon conclusion of the study: complete, honest information about the purpose of the experiment, the ways in which the data collected will be used, the reasons why deception was necessary, and the process to obtain additional information about the study.

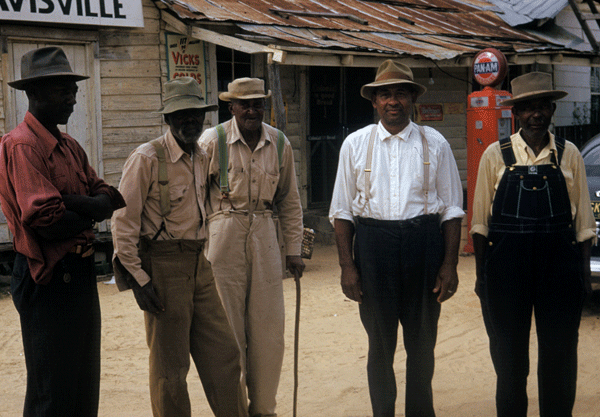

Today, scientists agree that good research is ethical in nature and guided by a basic respect for human dignity and safety. Unfortunately, the ethical guidelines that exist for research today were not always applied in the past. In 1932 poor, rural, Black, male sharecroppers from Tuskegee, Alabama, were recruited to participate in an experiment conducted by the US Public Health Service, with the aim of studying syphilis in Black men. In exchange for free medical care, meals, and burial insurance, 600 men agreed to participate in the study – 399 who tested positive for syphilis and 201 who did not have the disease. However, those individuals that tested positive were never informed that they had the disease. While there was no treatment for syphilis when the study began, by 1947 penicillin was recognised as an effective treatment for the disease. Despite this, no penicillin was administered to the participants in this study, and the participants were not allowed to seek treatment at any other facilities if they continued in the study. Over the course of 40 years, many of the participants unknowingly spread syphilis to their wives (and subsequently their children born from their wives) and eventually died because they never received treatment for the disease. This study was discontinued in 1972 when the experiment was discovered by the National Press (Tuskegee University, n.d.). The resulting outrage over the experiment led directly to the National Research Act of 1974 and the strict ethical guidelines for research on humans. Visit the CDC’s Tuskegee Timeline to learn more.

Research Involving Animals

Many psychologists conduct research involving animal subjects. Because many basic processes in animals are sufficiently similar to those in humans, these animals are acceptable substitutes for research that would be considered unethical in human participants. However, this does not mean that animal researchers are exempt from ethical concerns. The following are the Canadian Psychological Association’s (2017) guidelines on research with animals.

Research involving animals must:

- Treat animals humanely and not expose them to unnecessary discomfort, pain, or disruption.

- Not use animals in their research unless there is a reasonable expectation that the research will increase understanding of the structures and processes underlying behaviour, or increase understanding of the particular animal species used in the study, or result in benefits to the health and welfare of humans or other animals.

- Keep themselves up to date with animal care legislation, guidelines, and best practices, if using animals in direct service, research, teaching, or supervision.

- Use a procedure subjecting animals to pain, stress, or privation only if an alternative procedure is unavailable and the goal is justified by its prospective scientific, educational, or applied value.

- Submit any research that includes procedures that subject animals to pain, stress, or privation to an appropriate review panel or committee for review.

- Make every effort to minimise the discomfort, illness, and pain of animals. This would include using appropriate anaesthesia, analgesia, tranquilization and/or adjunctive relief measures sufficient to prevent or alleviate animal discomfort, pain, or distress, when using a procedure or condition likely to cause more than short-term, low-intensity suffering. It also would include, if killing animals at the termination of a research study, doing so as compassionately and painlessly as possible.

- Use animals in classroom demonstrations only if the instructional objectives cannot be achieved through the use of electronic recordings, films, computer simulations or other methods, and if the type of demonstration is warranted by the anticipated instructional gain.” (p. 24)

Animal experimental proposals are reviewed by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). An IACUC consists of institutional administrators, scientists, veterinarians, and community members. No animal research project can proceed without the committee’s approval. This committee also conducts semi-annual inspections of all animal facilities to ensure that the research protocols are being followed.

Opinions about using animals in research vary from wanting to completely stop using animals for research to strongly supporting it (Ormandy & Schuppli, 2014). Some people argue that it is morally unacceptable to experiment on animals, while others recognise the importance of animal research. For instance, drugs that can reduce the incidence of cancer or AIDS may be tested on animals first, and surgical procedures that can save human lives may be practiced on animals first. Furthermore, research on animals has contributed to a better understanding of the physiological reasons behind depression, phobias, stress, and various other illnesses. Considering the benefits that animal research brings, many scientists believe that this kind of research can and should continue, as long as we ensure the humane treatment of the animals involved.

Image Attributions

Figure PS.11. “IHA Board Meeting 56” by International Hydropower Association is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure PS.12. “Photograph of Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study” by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, n.d., in the National Archives Catalogue is in the public domain.

Figure PS.13. “Wistar rat” by Janet Stephens is in the public domain.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).