Chapter 18. Psychological Disorders

Diagnosing and Classifying Psychological Disorders

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 22 minutes

The first step in learning about psychological disorders is to carefully notice and understand the important signs and symptoms. How do experts figure out if someone’s feelings and actions are because of a psychological disorder? Making the right diagnosis (this means finding out what illness someone has by looking at their symptoms) is very important. This process helps experts speak the same language as others in their field and explain the disorder to the patient, other experts, and everyone else. Getting the diagnosis right is key to finding the best way to help someone get better. That’s why having a system to organise and name psychological disorders the right way is needed.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

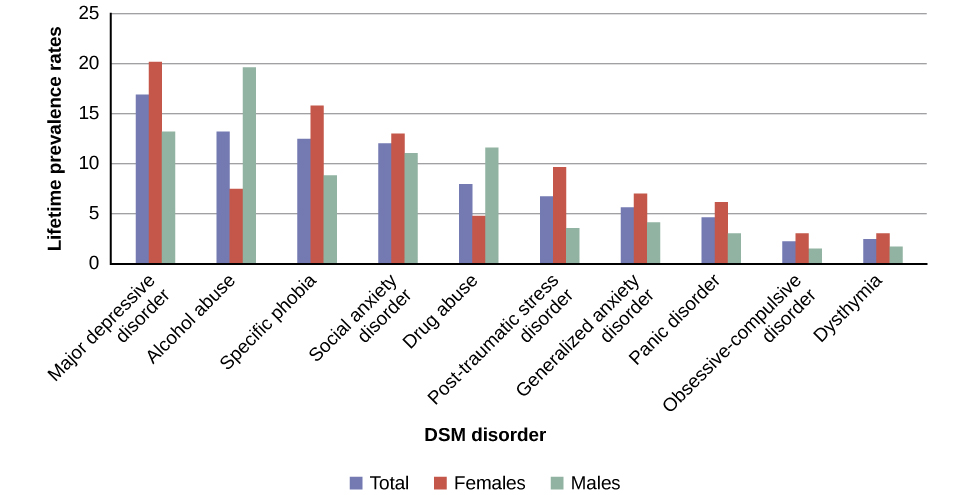

Although a number of classification systems have been developed over time, the one that is used by most mental health professionals in Canada and the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). (Note that the American Psychiatric Association differs from the American Psychological Association; both are abbreviated APA.) The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, classified psychological disorders according to a format developed by the US Army during World War II (Clegg, 2012). In the years since, the DSM has undergone numerous revisions and editions. The most recent edition, published in 2013, is the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM-5 includes many categories of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and dissociative disorders). Each disorder is described in detail, including an overview of the disorder (diagnostic features), specific symptoms required for diagnosis (diagnostic criteria), prevalence information (what percent of the population is thought to be afflicted with the disorder), and risk factors (things that can increase a person’s chance of developing a disorder) associated with the disorder. Figure PD.5 shows lifetime prevalence rates — the percentage of people in a population who develop a disorder in their lifetime — of various psychological disorders among adults in the US. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 US residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

DSM Versions: Imperfect and evolving criteria, standards and values

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has changed considerably in the half-century since it was originally published. Each version of the DSM reflects the evolving understanding of mental health, balancing improvements with ongoing challenges in accurately classifying and diagnosing mental disorders. The following is an overview of the increasing number of disorders and the improvements and problems with each version of the DSM.

- DSM-I (1952): Included 106 diagnoses.

- DSM-III (1980): Included more than 265 diagnoses.

- DSM-IV (1994): Included 297 disorders.

- DSM-5 (2013): Includes 237 disorders.

DSM-I (106 diagnoses) & DSM-II

- Improvements: Introduced standardised classifications for mental disorders.

- Problems: Homosexuality was wrongly listed as a disorder, reflecting the social prejudices of the time rather than an understanding of mental health (Silverstein, 2009).

DSM-III

- Improvements: Removed homosexuality as a disorder and detailed mental disorders more thoroughly, increasing the number of diagnosable conditions. The manual grew significantly in size and detail, indicating a more comprehensive approach to mental health.

- Problems: Introduced “ego-dystonic homosexuality”, which wrongly diagnosed homosexual arousal that the patient viewed as interfering with desired heterosexual relationships and causing distress for the individual as a disorder. This so-called disorder was likely included in the DSM as a compromise to anti-gay/lesbian people who still viewed homosexuality as a mental illness. Ego-dystonic homosexuality was controversial and questioned for its appropriateness (Herek, 2012).

DSM-III-R

- Improvements: Removed “ego-dystonic homosexuality” from the manual, moving further away from viewing homosexuality as a disorder (Herek, 2012).

- Problems: While it continued to detail disorders extensively, the rapid expansion of diagnosable conditions raised concerns about pathologisation (treating or considering a normal behaviour or condition as if it were a medical problem or illness).

DSM-IV

- Improvements: Continued to refine and expand the list of diagnosable conditions, offering a more finely detailed understanding of mental disorders.

- Problems: Despite its length and detail, some criticized it for pathologisation or potentially over-diagnosing or misclassifying normal variations in behaviour as disorders (Mayes & Horowitz, 2005).

DSM-5

- Improvements: Reduced the number of disorders, aiming for more accuracy in diagnosis. The latest edition, DSM-5, includes revisions in the organisation and naming of categories and in the diagnostic criteria for various disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2012), while emphasising careful consideration of the importance of gender and cultural difference in the expression of various symptoms (Fisher, 2010).

- Problems: While it aimed to address previous criticisms, its approach to certain conditions and the changes in classification and criteria continued to spark debate within the mental health community.

Tracking changes in the DSM manuals can be tricky. Here is one example of the imperfect, back and forth changes made in each consecutive DSM version. The DSM-IV specified that the symptoms of major depressive disorder must not be attributable to normal bereavement (loss of a loved one). The DSM-5, however, has removed this bereavement exclusion, essentially meaning that grief and sadness after a loved one’s death can constitute major depressive disorder.

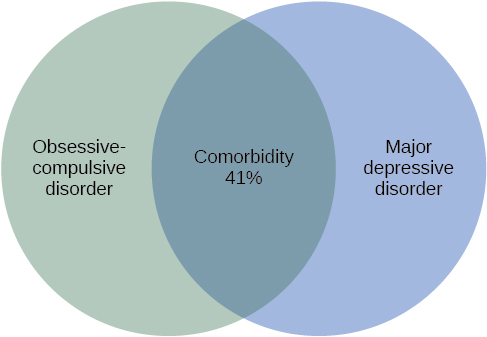

The DSM-5 also provides information about comorbidity — when two mental or physical health problems happen at the same time. For example, the DSM-5 mentions that 41% of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (Figure PD.6). Drug use is highly comorbid with other mental illnesses; 6 out of 10 people who have a substance use disorder also suffer from another form of mental illness (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2007).

Understanding Comorbidity

Comorbidity means having more than one health problem at the same time. Often, these different problems can make each other worse. It’s common for people to have more than one mental health issue. For example, many people who have serious mental health challenges also have problems with using drugs or alcohol. About 1 in 4 people with a severe mental illness also has issues with substance use. And, about 1 in 10 people looking for help with substance use also has a serious mental illness.

When someone has both a mental illness and uses drugs regularly, it can make their mental health symptoms stronger and harder to treat. It can be tricky to figure out if the symptoms are because of the drug use, the mental illness, or both. That’s why doctors suggest watching how someone acts after they’ve stopped using drugs and are not feeling sick from stopping the drug. This helps doctors make the best diagnosis (NIDA, 2018).

Substance use isn’t the only thing that can happen at the same time as mental health issues. Often, people with depression also feel very anxious. And, people with an anxiety disorder might also be very depressed. Anxiety and depression also happen a lot with other mental health problems (Al-Asadi, Klein, & Meyer, 2015).

The International Classification of Diseases

A second classification system, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), is also widely recognised. Published by the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD was developed in Europe shortly after World War II and, like the DSM, has been revised several times. The categories of psychological disorders in both the DSM and ICD are similar, as are the criteria for specific disorders; however, some differences exist. Although the ICD is used for clinical purposes, this tool is also used to examine the general health of populations and to monitor the prevalence of diseases and other health problems internationally (WHO, 2013). The ICD is in its 10th edition (ICD-10); however, efforts are now underway to develop a new edition (ICD-11) that, in conjunction with the changes in DSM-5, will help to harmonise the two classification systems as much as possible (APA, 2013).

A study that compared the use of the two classification systems found that the ICD is more frequently used worldwide for clinical diagnosis, whereas the DSM is more valued for research (Mezzich, 2002). Most research findings concerning the etiology (the underlying causes) and treatment of psychological disorders are based on criteria set forth in the DSM (Oltmanns & Castonguay, 2013). The DSM also includes more explicit disorder criteria, along with an extensive and helpful explanatory text (Regier et al., 2012). The DSM is the classification system of choice among US mental health professionals, and this chapter is based on the DSM paradigm.

Is this disorder describing me? When we talk about psychological disorders, keep two important ideas in mind. Psychological disorders are conditions in which people feel or act in ways that are much more extreme than usual. If you find yourself relating to some of the symptoms you read here, it’s okay — it usually just means you’re like everyone else. We all have times when we feel really sad, worried, or can’t stop thinking about something. It’s only a problem if these feelings or actions start to really disrupt your life.

Showing compassion for others. It’s important to see people with psychological disorders as more than just their condition. We avoid calling someone a “schizophrenic” or “depressive” because these words can make people seem like they are only their illness, which isn’t fair or true. Instead, we say “a person diagnosed with schizophrenia”, or “a person with depression symptoms”. Just like someone with cancer or diabetes, people with psychological disorders are dealing with tough, painful situations they didn’t choose. They deserve to be treated with kindness, understanding, and respect.

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Diagnosis (of Psychological Disorders) (10 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Diagnosis (of Psychological Disorders)” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.Here is the Tricky Topics: Diagnosis (of Psychological Disorders) transcript.

Image Attributions

Figure PD.5. Figure 15.4 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PD.6. Figure 15.5 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).