Chapter 12. Emotion

Emotion Introduction

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 12 minutes

Dr J’s Story: Part 1

In the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond, a pervasive myth claimed that women were more emotional than men. This stereotype, often voiced in popular media, workplaces, and classrooms, had profound societal implications, particularly in undermining women’s professional advancement and devaluing their personal experiences.

I was a direct witness to this misconception. Growing up with five brothers and a sister, I saw emotions expressed across the gender spectrum. For example, at my own wedding, I was full of emotion, tears streaming as I recited my vows and expressed my love for my husband. In truth, my sister said I did not cry — I “blubbered!” A decade later, my younger brother displayed a similar emotional intensity as he cried at his wedding, expressing his love and vows to his partner. Such observations taught me that emotions are not the exclusive domain of one gender. My lifetime of living with many brothers taught me that sometimes men in my family cry, other times they do not. Similarly, sometimes women in my family cry, other times they do not.

I realised early on that the stereotype of ‘women being too emotional’ was not only misleading but potentially harmful. It not only devalued women’s experiences and hindered their professional advancements, but it also dangerously underestimated the emotional lives of men. This injustice propelled me to delve deeper into the topic, and to begin an academic journey through researching my Master’s and Ph.D.

We will pause my research story here to start your exploration of emotions. At the end of this chapter, I will return to share an overview of my research (see section: ‘Are women more emotional than men? The short answer: No.‘) and tell you what I learned about the universality of emotional experience.

In our everyday language, the terms emotions, feelings, and moods are often used interchangeably. In psychological settings, these terms represent distinct psychological phenomena that play pivotal roles in shaping our reaction to and understanding of the world. In previous chapters, we looked at how our bodies are able to sense and perceive the world around us. In this chapter, we are going to look at how we make personal meaning out of those incoming external stimuli through our emotions, feelings, and moods.

First, we’ll dive into the scientific vocabulary that psychology researchers use to discuss emotions. After that, we will discuss some of the early academic/scientific theories about emotions and compare them to recent research findings. We will discover that there are several theories of emotions, some that contradict others. It is important for us to examine emotions from all perspectives. Our goal is not to find out, “which theory of emotion is most correct?” but rather ask, “which theory is useful in what contexts?”

We will broaden our review to include a brief overview of the theory of emotions in Traditional Chinese medicine. We will learn that emotions deeply interact with our organs and Nature’s elements.

Next, we’ll learn about the biology of emotions and the role of the amygdala and hippocampus.

We’ll explore emotional geographies — how our emotions may exist outside of us and do not surface until we come in contact with a certain place, time, or event. Understanding emotional geographies will also allow us to comprehend what Indigenous scholars mean when they say that the Land is a teacher and provides important lessons. By the end of this chapter, you’ll see how understanding our emotions is not just about what’s going on inside us, but also is highly interconnected to the world around us.

By understanding these ideas, we can appreciate the different ways people express and understand emotions. This knowledge is especially useful for those studying psychology, as it shows the variety of human experiences.

Additionally, we’ll delve into an interesting parallel to facial recognition: the struggles people with Autism Spectrum Disorder have with recognising emotions through facial expressions; and the role of emojis in writing as a mirror to our expressions, potentially enhancing our grasp and appreciation of subtle emotional details.

We will finish the chapter by answering the question, “Are women more emotional than men?” In this section, I share my (Dr J) journey from recording personal observations to researching with rigorous methodology to dispel this stereotype.

The Scientific Language of Emotion

Before we look at the selected theories, let’s start by scientifically defining some emotion-related terms that will give you a general overview of emotions before we look at each theory in detail.

Emotions

Emotions are complex physiological (physical) states that arise in response to specific stimuli or events. They are typically short-lived, intense, and have a clear cause or trigger, such as a specific event or situation (Garrido, 2015). For instance, the sudden rush of adrenaline you feel when confronted with danger or the warmth that envelopes you upon hearing good news are both manifestations of emotions. Emotions can encompass both positive and negative experiences.

Feelings a.k.a. “The feels”

Feelings, on the other hand, are our conscious experiences or subjective interpretations of these physiological-based emotions. For example, while an emotion might cause your heart to race, the feeling would be your conscious awareness or interpretation of this physiological response, such as recognising that you’re scared or excited (Barrett, 2017). For example, a person might say this to describe their feelings while listening to their favourite song. “Listening to that new song from my favourite artist gave me all the feels; it’s so relatable to what I’m going through right now!” We will discuss the important role of cognitive appraisal in depth later in this chapter.

Moods

Moods are longer-lasting affective states that might not have a clear cause. Unlike the transient nature of emotions, moods can linger, setting the tone for our day or even longer periods. They are often described as less intense but more persistent than emotions, subtly colouring our perceptions and behaviours over time (Garrido, 2015). For instance, while a feeling might be a sudden burst of happiness from receiving a compliment, a mood might be a general sense of contentment or melancholy that persists throughout the day.

Meta-moods

Mayer and Gaschke (1988) suggest that moods are composed of two parts: the immediate sensation of the mood itself and a reflective layer where one thinks and feels about that mood. They call this second layer “meta-moods” as it describes our internal dialogues and reflections on the moods we experience. For example, a meta-mood might be: “I seem to be always feeling anxious these days. I used to be so happy.” (Note: in psychology, “meta” is used to indicate we are ‘thinking about’ something, e.g., “meta-cognition” means thinking about how we think).

Emodiversity

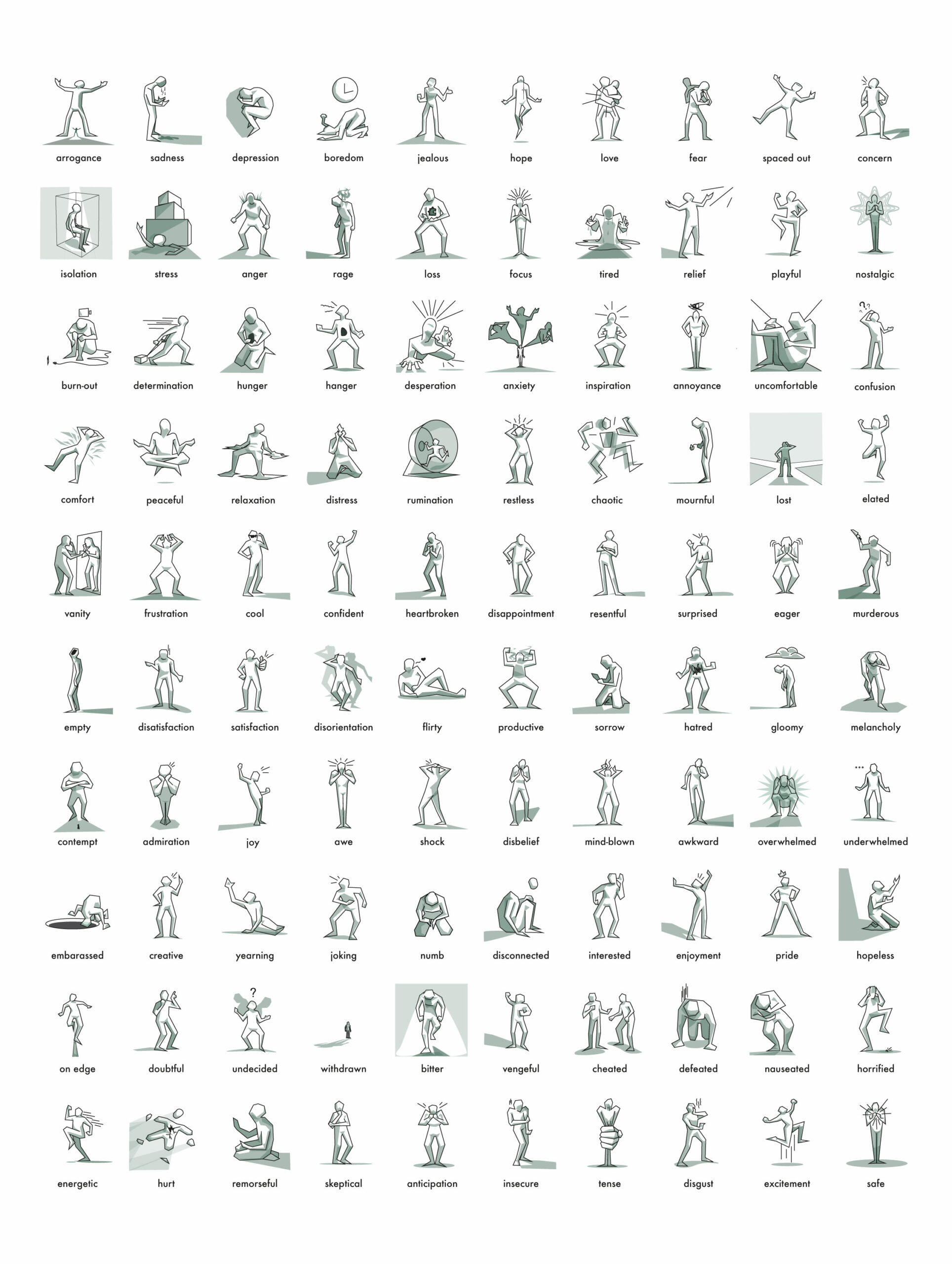

Emodiversity refers to the variety and relative abundance of emotions, signifying more than just increased positive or decreased negative feelings. Quoidbach et al. (2014) investigated 37,000 participants over two studies, and found that participants who experienced a wider range of emotions had less depression and fewer visits to medical doctors than those who experienced a narrower range of emotions. Emodiversity can be seen when different people move through their emotions at different rates and intensities (Figure EM.2)

These studies on emodiversity add to the already large amount of research that has demonstrated the advantages of leading a varied, genuine, and complex emotional life (e.g., Barrett, 2009, 2013; Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, 2009).

In essence, using an ocean metaphor, as we navigate the ocean of human experience:

- Emotions can be seen as waves that splash upon us

- Feelings are our personalized interpretations of and reactions to these waves

- Moods are the underlying currents that subtly push and pull our boat after the initial splashes

- Meta-moods are the stories we write in our journal about our ocean-based adventure

- Emodiversity comprises the overall changes in sizes of the splashes and waves that we encounter during moments of high and low tides.

Understanding these scientific terms for emotional experiences not only enriches our understanding of psychology but also provides insights into our own lives, enhancing our self-awareness.

Image Attributions

Figure EM.1. Emotions by Rachel Lu is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure EM.2. Toddler emotions by Marie Bartlett is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).