Chapter 17. Well-being

Happiness

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 33 minutes

Welcome to our exploration of happiness and well-being, vital areas in the study of psychology that touch every aspect of our lives. In this section on happiness we will discuss the biology, experiences, and theories that attempt to define our sense of happiness and overall well-being.

We explore the elements of happiness, looking at what truly makes us happy and how we can cultivate the pleasant life, the good life, and the meaningful life. We attempt to answer the question, “What Really Makes Us Happy?” We discuss how close relationships, money, education and religion may or may not enhance well-being.

Next, we attempt to answer the question, “Can we make ourselves happier?” The good news is that we can actively work on improving our happiness. We consider positive psychology, which shifts the focus from treating mental illness to enhancing well-being. This field looks at what makes life worth living, exploring aspects like empathy, creativity, and positive emotions. It’s about building on our strengths and fostering those qualities that contribute to a fulfilling and happy life. We also explore Seligman’s PERMA model, which breaks down the building blocks of a fulfilling life through Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.

We then examine the concept of negativity bias, which is our brain’s tendency to focus more on negative experiences than positive ones. By consciously acknowledging and savoring positive experiences, we can counteract this bias and improve our mental health and well-being. This involves seeking out positive moments, savoring them, soaking in the good experiences, and sustaining these practices regularly.

In addition, we discuss the role of gratitude in enhancing happiness. Practicing gratitude can significantly enhance happiness. By focusing on what we are thankful for, even in challenging times, we can shift our perspective and improve our overall satisfaction with life.

Finally, we discuss the pursuit of happiness from different cultural perspectives. Different cultures view happiness differently. In individualistic cultures, happiness is often seen as something to pursue and achieve. In collectivistic cultures, happiness is more about being content with what you have and your place in the community. Understanding these perspectives can enrich our own approach to finding contentment and joy.

Through these discussions, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of what constitutes happiness and how we can cultivate it in our lives. Are you ready to learn about happiness? Let’s begin!

Elements of Happiness

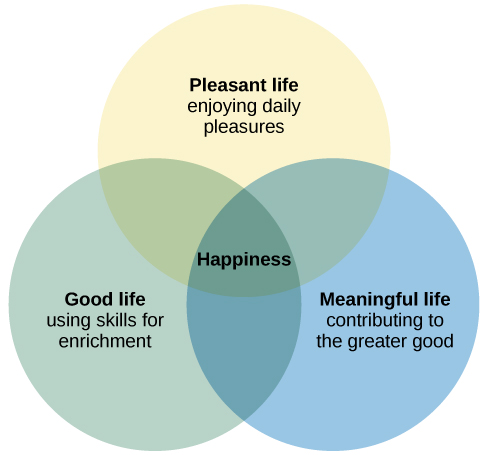

Psychologists say happiness has three parts: the pleasant life, the good life, and the meaningful life (Seligman, 2002; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). The pleasant life is about enjoying everyday pleasures that bring fun and excitement, like beach walks or a satisfying love life. The good life happens when we use our unique skills and get really into our work or hobbies. The meaningful life comes from using our talents for a greater cause, like helping others or improving the world. Generally, the happiest people focus on all three parts (Seligman et al., 2005).

To put it simply, happiness is a lasting feeling of joy, contentment, and the sense that your life is valuable (Lyubomirsky, 2001). It’s more than just feeling good temporarily; it’s about feeling good in the long run, known as subjective well-being.

What Really Makes Us Happy?

Researchers have spent years trying to figure out what makes us truly happy, examining factors such as money, appearance, possessions, enjoyable jobs, and strong relationships. Here’s a summary of their findings:

As people age, they generally feel more satisfied with life, and this sense of happiness doesn’t really differ among the genders. Being in close relationships, such as a happy marriage, significantly boosts happiness. Those in strong marriages or with solid social connections are often happier than those who are single, divorced, or widowed. Money does play a role in happiness, but only up to a point. People in wealthier countries and those with higher incomes tend to be happier, but this only holds true until around $75,000 per year. Beyond that, more money doesn’t necessarily add to happiness and can even make it harder to enjoy the simple pleasures in life.

Education and meaningful employment are linked to happiness, with graduates and those in fulfilling jobs reporting higher levels of satisfaction. However, intelligence by itself doesn’t guarantee happiness. Religion can contribute to happiness, especially in tougher living conditions, with religious people often reporting greater well-being. Cultural fit also matters; people whose personalities and values align with their culture’s tend to be happier.

Interestingly, having children and physical attractiveness don’t have a strong connection to happiness. Studies suggest that people without children can be just as happy, if not happier, than people with children, and feeling good about one’s appearance is more important than actual looks. This research highlights that happiness stems from a mix of factors, including quality relationships, financial security up to a point, fulfilling work, and a good cultural and personal fit, rather than from wealth, looks, or other external factors alone.

It’s important to know that we’re not always great at predicting our future emotions, a concept called affective forecasting (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). For instance, most newlyweds think they’ll stay as happy as they are or become even happier, but a study found that their happiness actually went down over four years (Lavner, Karner, & Bradbury, 2013). We also often guess wrong about how big life events will change our happiness. For example, we might think winning the lottery or dating a famous person would make us forever happy, or that we’d be forever sad if we had a bad accident or a breakup.

But, just as our senses adjust to new situations (like our eyes getting used to bright light after exiting from a dark movie theatre), our emotions adjust to big changes in our lives (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Helson, 1964). Initially, something good or bad can make us feel very happy or very sad. But over time, we get used to these changes, and our happiness level often goes back to what it was before. So, even exciting events like winning the lottery or your favourite team winning a big game eventually become normal (Brickman, Coats, & Janoff-Bulman, 1978).

Can We Make Ourselves Get Happier?

Some studies show that we can actually change our happiness levels for the better. For example, well-designed happiness programs can help people feel happier for a long time, not just for a moment. These programs can work for individuals, groups, or whole societies (Diener et al., 2006). One study found that simple activities like writing down three good things each day made people happier for over six months (Seligman et al., 2005).

If we measure happiness across societies, it can tell policy makers whether or not people are happy, and why. Research shows that a country’s average level of happiness is linked to six things: the country’s wealth (GDP), support from others, choices in how to live one’s life, a long, healthy life, government and businesses that people trust, and personal generosity (Helliwell et al., 2013). Understanding why people are happy or not can help governments create programs to make their societies happier (Diener et al., 2006). Decisions about important issues like poverty, taxes, healthcare, housing, clean environment, and income differences should consider how they will affect people’s happiness.

Positive Psychology

Positive psychology, pioneered by Seligman in 1998, represents a significant shift in the focus of psychological research and practice. Unlike traditional psychology, which often centres on addressing mental illness and emotional difficulties, positive psychology aims to enhance the well-being and flourishing of individuals by understanding and promoting enduring aspects of human experience that contribute to a fulfilling life (Compton, 2005). This field explores valuable experiences like well-being, contentment and happiness. Positive Psychology also examines positive traits, such as the ability to love, have courage, be creative, develop wisdom, be kind, forgive, show positive emotions, improve immune system health, develop character virtues and enjoy life. (Compton, 2005).

The scope of positive psychology includes research areas like altruism (being of service to others), empathy, creativity, and the impact of positive emotions on immune system functioning, as well as how savouring life’s moments and developing virtues contribute to authentic happiness. Positive Psychology also focuses on how to resolve conflict and foster peace and well-being at the community and global level (Cohrs, Christie, White, & Das, 2013).

PERMA Model + Flow

Seligman’s PERMA model is a way to understand what makes life most fulfilling and happy. “PERMA” stands for Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. These five aspects plus Flow (when you’re really into something you’re doing, so much that you forget about time and everything else around you) are key ingredients for a good life, according to positive psychology, a branch of psychology that focuses on what makes life worth living.

- Positive Emotions: Feeling good and experiencing joy, gratitude, optimism, and other positive feelings that uplift us.

- Engagement: Being deeply involved and absorbed in activities that challenge and utilise our skills and interests.

- Relationships: Building strong, supportive connections with others that bring love, belonging, and social support.

- Meaning: Finding a sense of purpose and understanding that we are part of something bigger than ourselves.

- Accomplishment: Pursuing goals, overcoming challenges, and achieving success that contributes to a sense of fulfilment and pride.

Both flow and engagement help us feel more connected to what we are doing and give us a sense of satisfaction. They are crucial for our well-being because they make us feel alive and part of something bigger. When we experience flow and engagement, we are using our strengths and abilities to their fullest, which is a key part of being happy and fulfilled.

Rewiring for Happiness: Overcoming the Brain’s Negativity Bias

Understanding how to rewire our brains for happiness involves recognising a concept known as the negativity bias. This term refers to our brain’s tendency to give more attention and weight to negative experiences than to positive ones (Hanson & Mendius, 2009; Rozin & Royzman, 2001). This bias isn’t merely a result of our genetic makeup; it’s also shaped by our experiences throughout life. It manifests in various ways, including our stronger reactions to negative events and our tendency to recall unpleasant experiences more vividly than pleasant ones (Monterrubio, Andriotis, & Rodríguez-Muñoz, 2020; Everly Jr. & Lating, 2019).

While our negativity bias has roots in our evolutionary past — serving as a survival mechanism by making us more alert to potential threats — its usefulness extends into modern life. Our negativity bias can prompt us to evaluate risks carefully and make decisions that protect us from harm. This cautious approach can be beneficial in complex social situations and professional environments, where anticipating challenges and preparing for possible mistakes or complications can lead to better outcomes.

However, the harms caused by our negativity bias are significant and can affect various aspects of our lives. Overemphasis on negative experiences can cause us to experience chronic stress, anxiety, and depression. It can distort our perceptions, making us more likely to see threats where none exist and undervalue positive aspects of our lives. This skewed perspective can hinder our personal growth, strain our relationships, and reduce our overall life satisfaction. Furthermore, in professional settings, a strong negativity bias might stifle creativity and innovation, as the fear of failure or criticism can prevent us from taking the necessary creative risks.

It’s crucial for us to balance our in born negativity bias with a conscious effort to acknowledge and savour positive experiences. By doing so, we can lessen the impact of negativity bias on our mental health and overall well-being. Developing a more balanced perspective allows us to enjoy a fuller, more satisfying life in which we’re not focused just on avoiding the bad but also embracing the good. By actively working to balance our perspective, we can mitigate these negative effects. This involves practices such as mindfulness, gratitude journaling, and positive reframing, which help us to notice and appreciate the positive aspects of our experiences. Over time, these practices can help rewire our brains to become more attuned to positivity, fostering a healthier, more resilient mindset.

Experience-Dependent Neuroplasticity: Shaping the Brain

In this section, we will explore the biological and psychological ways our negativity bias, neuroplasticity (physical brain changes) and our experiences, especially those we’re conscious of, interact and actively shape the structure of our brain. We will also explore the pivotal role of a process called experience-dependent neuroplasticity in reshaping our neural pathways (Hanson, 2013).

Negativity Bias

As mentioned above, the concept of negativity bias refers to the phenomenon of negative events that have a greater impact on one’s psychological state and processes than do positive or neutral events. This bias is thought to have an evolutionary basis, providing an advantage for survival by prioritising the avoidance of harmful stimuli over seeking potential benefits (Vaish, Grossmann, & Woodward, 2008). At the neurobiological level, the amygdala, a part of the brain known for processing emotions, especially fear and threat, plays a significant role in negativity bias. When negative stimuli are encountered, the amygdala activates more intensely compared to positive or neutral stimuli, leading to stronger and more lasting emotional and cognitive impacts (Cisler & Koster, 2010). This heightened amygdala response results in stronger memory formation of negative events and a tendency for these memories to be more easily recalled, further reinforcing the bias (Roozendaal, McEwen, & Chattarji, 2009).

Experience-based neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s capability to structurally and functionally evolve in response to experiences. This involves the principle whereby neurons that frequently activate together strengthen their connections, enhancing efficiency and likelihood of simultaneous activation. Key to this process are the amygdala and hippocampus. The amygdala processes emotions, impacting how emotional experiences shape the brain, while the hippocampus, vital for memory formation, collaborates with the amygdala to solidify and preserve emotional memories. These interactions enable continuous emotional experiences to instigate enduring alterations in the brain’s architecture and functionality (LeDoux, 2000).

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s way of being flexible and adaptable, enabling learning and memory, as well as recovery from brain damage. It operates through mechanisms such as long-term potentiation (LTP, a process that strengthens the connections between neurons when they are frequently used together) and long-term depression (LTD, a process that weakens the connections between neurons when they are less frequently used). This process is significantly influenced by brain chemicals like glutamate and specific receptors (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2007), which act like messengers and locks that control the flow of signals in the brain. The basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA, a part of the brain involved in processing emotions) also plays a crucial role in this dynamic by modulating (adjusting) memory formation through its interactions with the hippocampus, an area of the brain critical for memory. This not only affects memory but also impacts synaptic connectivity (how neurons connect and communicate with each other) and gene functionality within the hippocampus (Maren & Quirk, 2004).

The concept of “neurons that fire together, wire together” sums up the lasting and brain-changing impact of frequent and conscious thoughts or activity patterns on our brain, similar to how a river shapes its bed over time. Essentially, the more often certain neurons activate together, the stronger their connection becomes, shaping our brain’s structure and function. As such, the thoughts and actions we repeatedly engage in physically sculpt our brain over time. This aspect of neuroplasticity highlights the importance of focusing on positive experiences and thoughts, as doing so can cultivate (develop and strengthen) a brain that is more resilient (better at recovering from stress or trauma), optimistic, and positive.

By understanding and applying these principles, we can actively work towards rewiring our brains for happiness, counteracting our natural negativity bias. This process involves not just ignoring out doom-related, improbable, negative possibilities and scenarios, but also, actively strengthening our positive thoughts, leading to lasting changes in our neural networks (the complex web of neuron connections) and overall well-being.

Practical Steps to Rewire the Brain

Now that we have discussed the process of neuroplasticity and the concept of negativity bias, let’s look at practical steps to apply this knowledge. This section introduces a simple mnemonic to help us remember the rewiring steps recommended by Hanson and backed up by research evidence about how to rewire our brains from a negativity bias towards a practice of happiness.

Here is a simple mnemonic to help you remember the four steps Hanson outlines to help us to rewire our brains away from a negativity bias toward a new happiness outlook: Seek. Savour. Soak. Sustain.

- SEEK. Experience Positive Moments: Hanson (2013) emphasises the importance of actively seeking and engaging in positive experiences. These can range from simple physical sensations like relishing the taste of good coffee to enjoying positive social interactions and appreciating the beauty in our surroundings.

- SAVOUR. Deepen the Experience: To counteract the negativity bias, it’s essential to savour these positive experiences. Hanson suggests staying with a positive experience for 20-30 seconds, feeling it in the body and emotions. This practice aligns with research showing that emotional intensity and duration of awareness strengthen neural connections and memory traces (Goldstein-Piekarski et al., 2021; Qasim, Mohan, Stein, & Jacobs, 2021; McGaugh, 2015).

- SOAK. Soak in the Good Experience: Beyond just savouring, Hanson (2013) advises allowing the positive experience to deeply embed itself in our consciousness. This process involves a more passive and receptive state of mind, where we let the positive feelings seep into our awareness, contributing to long-term emotional memory.

- SUSTAIN. Practice Regularly: Regular practice of these steps in various situations can help rewire the brain to respond more positively or neutrally to unexpected events, reducing anxiety and fostering a more balanced approach to life’s uncertainties (Hanson, 2013).

The PERMA Model (discussed above and refer to Supplement WB.9), offers a comprehensive framework that goes beyond the brain’s wiring to encompass the various dimensions of a fulfilling life. This model doesn’t just focus on internal cognitive processes but extends to external aspects of our lives, including our relationships, achievements, and sense of purpose. As we transition from the individual-focused strategies of rewiring our brains, the PERMA Model invites us to consider the wider sources of connections that contribute to our overall happiness and life satisfaction (Seligman, 2018)

In the realm of positive psychology, Seligman’s PERMA model stands out as a comprehensive framework for understanding well-being and happiness. Seligman invites us to not just survive, but to truly thrive. This model is particularly useful in helping us understand that well-being. It’s a tool for individuals and communities to assess their well-being and to find areas for enhancement and growth. It encourages a holistic approach to building a fulfilling life, combining emotional well-being with engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment.

Rewiring for happiness through the lenses of PERMA Model + Flow provides an explanation of what it means to live a fulfilled and happy life. We are reminded that happiness is not just a state of mind influenced by our neurological pathways but also a holistic experience shaped by our relationships, activities, achievements, and sense of purpose. Where we direct our energy plays a big role in our experience of happiness or stress.

Uplifts and Hassles. Glimmers and Triggers.

Navigating the ups and downs of daily life often feels like a balancing act between positive and negative experiences. In this section, we delve into the concepts of uplifts and hassles, as well as glimmers and triggers, to understand how they shape our well-being. Uplifts are those small, positive moments that brighten our day, such as a kind word from a colleague or a personal accomplishment. In contrast, hassles are the daily stressors and annoyances that can accumulate and weigh us down. Understanding how these experiences affect us can provide valuable insights into maintaining a healthy and balanced life.

We also explore Polyvagal Theory, which explains how our nervous system responds to feelings of safety or threat through glimmers and triggers. Glimmers are subtle cues that promote a sense of calm and connection, while triggers can activate stress and defensive responses. By recognizing and fostering glimmers and managing triggers, we can enhance our resilience and overall well-being.

Uplifts and Hassles

Uplifts are positive experiences that can counterbalance the negative effects of hassles. These include experiences of accomplishment, positive interactions with colleagues, recognition, and support from management. Uplifts can also come from praying, thinking fondly about the past, feeling safe, laughing, socializing, and gossiping. Such positive experiences can significantly enhance an individual’s sense of well-being and job satisfaction, providing a buffer against stress and burnout (Miller & Wilcox, 1986).

Hassles refer to the daily irritations, frustrations, and stressful demands that employees encounter. These can range from minor annoyances like paperwork and routine tasks to more significant stressors such as conflicts with colleagues or overwhelming workloads. When these hassles accumulate, they can lead to chronic stress and negatively impact mental and physical health (Delongis et al., 1982).

Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, explains how the autonomic nervous system regulates our physiological state in response to perceived safety or threat (Porges, 2011). According to this theory, our nervous system operates through three primary states: the ventral vagal state (associated with safety and social engagement), the sympathetic state (associated with fight or flight responses), and the dorsal vagal state (associated with shutdown or freeze responses).

Glimmers and triggers are concepts within Polyvagal Theory (suggested by Dana, 2018) that describe the small moments or cues that can either promote a sense of safety (glimmers) or trigger a defensive response (triggers).Glimmers are those positive, often subtle, experiences that can shift us towards the ventral vagal state, enhancing our sense of connection, calm, and well-being. Glimmers might include a friendly smile from a colleague, a compliment from a supervisor, or even the satisfaction of completing a task. Recognizing and fostering these glimmers can help create a supportive and positive work environment.

In personal life, glimmers can also play a crucial role in enhancing our sense of well-being. These can include small, positive experiences such as receiving a warm hug from a loved one, hearing your favourite song, spending time in nature, or engaging in a hobby. Even simple acts like petting an animal, cooking a favourite meal, or receiving a thoughtful message from a friend can serve as glimmers. These moments help shift us towards a state of calm and connection, contributing to our overall resilience and happiness.

Triggers, on the other hand, are cues that can activate our sympathetic or dorsal vagal responses, leading to stress, anxiety, or feelings of overwhelm. These might include a critical remark from a manager, a looming deadline, or a tense meeting with a colleague. Understanding these triggers and how they affect our physiological state can help us develop strategies to manage our responses more effectively (Porges, 2011).

In personal life, triggers can include everyday stressors such as arguments with family members, financial worries, traffic jams, or even unexpected bills. Negative interactions on social media, feeling overwhelmed by household chores, or receiving bad news can also serve as triggers. Recognizing these triggers helps us to better manage our reactions, thereby reducing stress and promoting a more balanced and healthy life.

By promoting uplifts and recognizing the positive effects of glimmers, we maintain a balanced our autonomic state, supporting our overall health and productivity. We can amplify the effects of glimmers by practising mindfulness, taking regular breaks, and engaging in positive social interactions.

We can manage or diminish the effects of triggers by identifying and understanding them, which allows us to develop effective coping strategies. Techniques such as deep breathing exercises, physical activity, and seeking social support can help reduce the impact of triggers. Additionally, practicing self-compassion and reframing negative thoughts can further mitigate the stress and anxiety caused by these triggers. By balancing the promotion of uplifts and glimmers with the management of triggers, we enhance our overall well-being and resilience.

In exploring uplifts and hassles, and glimmers and triggers, we gain a deeper appreciation for the small yet powerful influences on our daily lives. By focusing on the positive experiences and managing the negative ones, we can create a more balanced and fulfilling life. Understanding the physiological basis of our responses through Polyvagal Theory empowers us to foster environments, both at work and at home, that support our mental and physical health. As we move forward, let’s remember we can cultivate our glimmers and reduce the impact of our triggers to increase our well-being and resilience.

What simple uplifts and glimmers can you incorporate into your daily routine to transform your sense of well-being and resilience?

Gratitude

Next in our exploration of happiness and well-being is a podcast episode featuring Dr. Laurie Santos, a distinguished Yale Psychology Professor and the voice behind The Happiness Lab podcast. In this episode, Dr. Santos delves into the role of gratitude in enhancing happiness. She sheds light on how nurturing a sense of gratitude can lead to higher levels of happiness and satisfaction in life. The episode goes beyond the surface, distinguishing between authentic gratitude practices and the concept of toxic positivity. It offers practical advice on integrating mindfulness and gratitude into daily life, emphasising the importance of acknowledging life’s blessings, even in challenging times.

Watch this video: Podcast: The Power of Gratitude with Dr. Laurie Santos (5 minutes)

“Podcast: The Power of Gratitude with Dr. Laurie Santos” video by Headspace is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

The “Pursuit” of Happiness?

The term “pursuit of happiness” describes how some people with individualistic values think about happiness. They can often believe that happiness is something they need to chase after or work hard to get. They think being free, showing who they really are, and achieving their goals will make them happy. But this idea also means that happiness is something you have to chase, and you might not always catch it.

In other parts of the world, like Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and in Indigenous cultures, people see happiness differently. For these collectivistic cultures, happiness isn’t really about chasing after things. Instead, it’s about how people feel about their life as it is. They find happiness in living in the moment and being part of their community. It’s not about doing specific things to be happy; it’s more about feeling content with where you are and who you’re with.

Summary

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).