Chapter 13. Motivation

Hunger, Eating, and the Motivation Behind Our Food Choices

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 40 minutes

Content Disclosure and Reader Advisory

This section delves into topics related to hunger, eating behaviours, body weight, and the complex psychological and physiological underpinnings of these experiences. We will explore the mechanisms of hunger and satiety, the scientific and societal debates surrounding body weight, including the distinctions between ‘normal’ weight and ‘healthy’ weight, and the critical issues of obesity, eating disorders, and weight bias discrimination.

Please be aware that discussions on these topics might be sensitive for some readers, particularly those with personal experiences related to eating disorders, weight discrimination, or body image concerns. If you find any topic particularly challenging, we encourage you to approach this content with care and seek support if needed. This section is designed to inform and educate, and foster a deeper awareness of the motivations behind our food choices and the societal factors that influence our relationship with food and body image.

Let’s look more closely at one of our many human drives — hunger. In this discussion of hunger and eating, we’re not just going to talk about why your stomach rumbles before lunch. We will explore the physiological mechanisms that drive our hunger; the debate between the set-point theory and the settling point model in understanding body weight; and the distinction between “normal” weight and “healthy” weight; obesity; the often-overlooked problem of weight bias discrimination, and eating disorders.

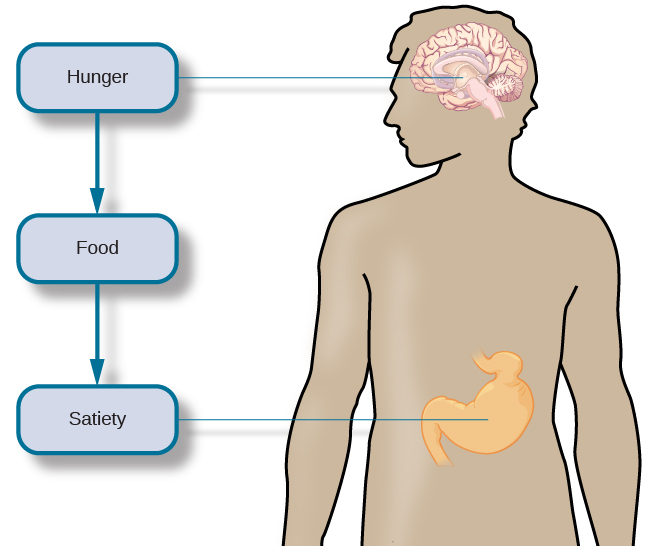

There are several physiological mechanisms that underlie hunger. When our stomachs are empty, they contract, causing hunger pangs and the secretion of chemical messages that travel to the brain, signalling the need to initiate feeding behaviour. Additionally, when our blood glucose levels drop, the pancreas and liver produce chemical signals that induce hunger (Konturek et al., 2003; Novin, Robinson, Culbreth, & Tordoff, 1985), prompting us to eat.

Satiety and Its Role in Eating Motivation

Satiety is the feeling of being full and satisfied after eating food. It’s what can signal to you to stop you from wanting to eat more once you’ve had enough.

For many individuals, eating leads to satiation, a sense of fullness and satisfaction, which halts their eating behaviour. Like the initiation of eating, satiation is regulated by several physiological mechanisms. As blood glucose levels rise, the pancreas and liver send signals to suppress hunger and eating (Drazen & Woods, 2003; Druce, Small, & Bloom, 2004; Greary, 1990). The passage of food through the gastrointestinal tract also sends important satiety signals to the brain (Woods, 2004), and fat cells release leptin, a hormone that promotes satiety.

The various hunger and satiety signals involved in regulating eating are integrated in the brain. Research indicates that several areas of the hypothalamus and hindbrain are particularly crucial for this integration (Ahima & Antwi, 2008; Woods & D’Alessio, 2008). Ultimately, it is brain activity that determines if we engage in feeding behaviour.

Traditionally, hunger has been viewed primarily as a physiological drive, a biological signal indicating the need for food for energy and survival. However, more recent theorists suggest that hunger is not solely a biological experience but is also deeply intertwined with cultural and psychological factors. Schwartzman (2015) suggests that hunger includes not only the physical need for food but also psychological and social components, such as emotional fulfilment and societal norms around eating. This perspective suggests that a comprehensive understanding of hunger requires a broader lens, encompassing gender dynamics and cultural influences.

Metabolism and Body Weight

“Normal weight” is not the same as “healthy weight.”

“Normal weight” and “healthy weight” are terms often used when discussing body weight, but they don’t mean the same thing.

- Normal weight refers to the statistical average weight of a specific population. It’s a figure that represents the most common weight among a group of people. However, being average doesn’t necessarily equate to being healthy.

- Healthy weight, on the other hand, is a weight range associated with the lowest health risks and optimal health outcomes. Unlike “normal weight,” which is purely statistical, “healthy weight” considers various factors that influence health, including age, sex, muscle-fat ratio, and bone density. This range is linked to a minimal risk of weight-related diseases and conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension (Willett et al., 1995; Yi et al., 2015).

The distinction is crucial because a weight that is “normal” or average within a population might not be ideal for health. For instance, the average weight for Canadian adults might be higher than what is considered healthy based on Body Mass Index (BMI) guidelines. This discrepancy highlights that “normal” weight can sometimes be misleading if used as a health standard (Adhikari, 2016; Statistics Canada, 2015; Williamson, 1993).

In addition, the term “normal” can be problematic because it reflects mainstream cultural norms, which do not represent everyone. For example, body weights that are common in other cultures might not align with what is considered “normal” in European-settler culture, leading to unfair and inaccurate health assessments (Saguy, Gruys, & Gong, 2010; Pyke, 2000). This is particularly evident in the differing perceptions of “normal body weight” among African-American women compared to government health guides (Gore, 1999; Kumanyika, 1995).

Therefore, focusing on “healthy weight” is more scientifically accurate and culturally informed than saying “normal weight” when discussing health. This “healthy weight” approach prioritises well-being over statistical norms or cultural expectations, making it more inclusive and relevant to individuals from diverse backgrounds.

Our body weight is influenced by various factors, including gene-environment interactions and the balance between the number of calories we consume and the number of calories we burn through daily activities. If our caloric intake exceeds our caloric use, our bodies store the excess energy as fat. Conversely, if we consume fewer calories than we burn, stored fat is converted into energy. Our energy expenditure is obviously affected by our activity levels, but our body’s metabolic rate also plays a role. A person’s metabolic rate is the amount of energy expended over a given period, and there is significant individual variability in metabolic rates. People with high metabolic rates can burn off calories more easily than those with lower rates.

We all experience weight fluctuations from time to time, but generally, most people’s weights remain within a narrow range unless there are extreme changes in diet and/or physical activity. This observation led to the proposal of the set-point theory of body weight regulation. The set-point theory states that each individual has an ideal body weight, or set point, that is resistant to change. This set point is thought to be genetically predetermined, and efforts to significantly alter our weight from this set point are met with compensatory changes in energy intake and/or expenditure (Speakman et al., 2011). However, some predictions from this theory have not been empirically supported. For instance, there are no changes in metabolic rate between individuals who have recently lost significant amounts of weight and a control group (Weinsier et al., 2000). Additionally, the set-point theory does not fully account for the influence of social and environmental factors in the regulation of body weight (Martin-Gronert & Ozanne, 2013; Speakman et al., 2011).

Newer models like the settling point model challenge the set-point theory, suggesting that body weight settles based on a combination of genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and lifestyle, rather than a predefined set point (Keijer et al., 2014). Furthermore, the distinction between metabolic and hedonic obesity adds depth to our understanding of body weight regulation. Metabolic obesity is characterised by an increased body weight due to a higher metabolic set point, where the body naturally maintains a higher weight despite normal energy intake and expenditure. In contrast, hedonic obesity is driven by overeating due to external cues and pleasure-seeking behaviours, often unrelated to energy needs. This distinction indicates that factors beyond a simple set point, such as behavioural and environmental influences, play a significant role in body weight regulation (Yu et al., 2015).

Despite these limitations and challenges, set-point theory is still often used as a straightforward, intuitive explanation for how body weight is regulated.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a mental health condition where a person can’t stop thinking about one or more perceived defects or flaws in their appearance — a flaw that, to others, could even be minor or not observable. This worry about perceived ‘defects’ can cause significant distress and may lead to hours spent examining themselves in a mirror, seeking reassurance, or even undergoing cosmetic procedures with little satisfaction in the results (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

People with BDD often have a hard time controlling their negative thoughts and spend a lot of their day worried about their appearance. This worry isn’t just vanity; it’s a serious anxiety that can affect someone’s ability to live a normal life. For example, they might avoid social situations, leading to loneliness and isolation, or they might miss work or school because of their intense focus on their appearance (Phillips, 2005).

For individuals whose felt sense of gender does not align with their external appearance, BDD can be particularly distressing. The incongruence between their internal gender identity and their body shape or features can exacerbate feelings of dysphoria and lead to heightened anxiety and depression. Compassionate and gender-affirming care is crucial in these cases, as addressing both the body image concerns and the underlying gender dysphoria can help alleviate some of the intense distress associated with BDD.

Treatment for BDD usually involves a combination of psychotherapy and medication (or in the case of gender-related BDD, gender affirming care). Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be effective in helping individuals to challenge and change their negative thoughts about their body image and learn healthier ways to cope with their concerns (Wilhelm et al., 2014). If you or someone you know might be struggling with BDD, it’s important to seek help from a mental health professional. Understanding and addressing this disorder early can significantly improve a person’s quality of life.

Content disclosure: This video is age-restricted because it includes discussion of eating disorders, self harm, illness, and deaths as a result of anorexia and other eating disorders. For example, “anorexia has what’s often estimated to be the highest rate of mortality of any psychiatric disorder. (at 3:52)”

Watch this video: Eating and Body Dysmorphic Disorders: Crash Course Psychology #33 (10 minutes)

“Eating and Body Dysmorphic Disorders: Crash Course Psychology #33” video by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Obesity

Understanding Obesity

Obesity has often been narrowly viewed as a result of individual lifestyle choices and lack of self-control. Contemporary feminist theories challenge this individualistic view and highlight the role of societal and cultural factors in obesity. Aston et al. (2012) argue that obesity must be understood within its broader environmental and cultural contexts, where societal norms and media representations play a significant role (Aston et al., 2012).

Obesity is a complex topic in the medical and psychology community, with ongoing debates about whether it should be classified as a disease. Those in favour of this classification argue that obesity involves specific genetic and environmental factors that lead to harmful health conditions, such as insulin resistance and cardiovascular diseases. By recognizing obesity as a disease, they believe it would provide more medical legitimacy, improve healthcare access, and reduce societal stigma.

On the other hand, critics argue that labeling obesity as a disease could undermine personal responsibility, encourage unhealthy lifestyles, and lead to overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments. They also point out that BMI, often used to define obesity, doesn’t account for individual health differences and could inaccurately categorize people as obese.

A balanced approach acknowledges that obesity can be both a disease and a risk factor. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission is working to establish clinical criteria for diagnosing obesity based on biological and clinical signs, rather than solely on BMI. This effort aims to better identify and treat obesity, improve public health strategies, and reduce weight-related stigma (Rubino, et al., 2023).

Body Mass Index (BMI)

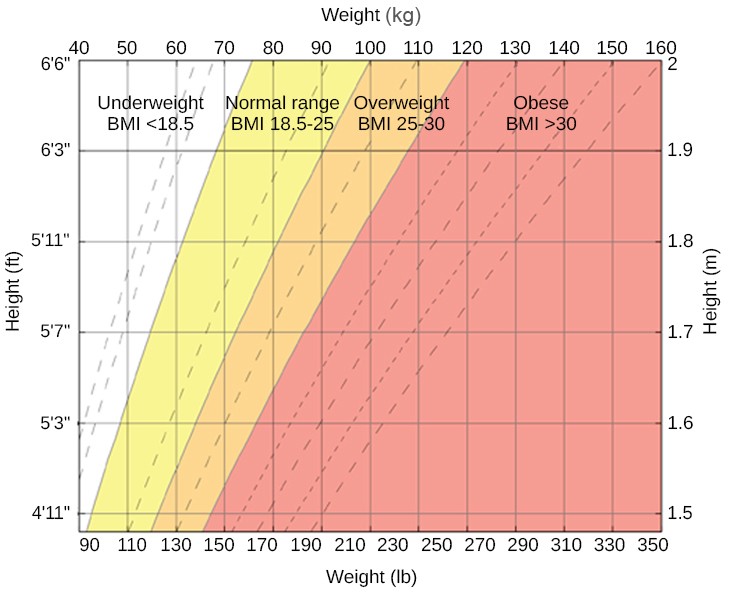

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a way to figure out if a person’s weight is healthy for their height. It’s calculated by taking someone’s weight in kilograms and dividing it by their height in metres squared. The result gives a number that helps health professionals understand if a person is underweight, at a healthy weight, overweight, or obese. BMI is like a quick math check to see how your weight matches up with your height.

Definitions

When someone weighs more than what is generally accepted by physicians as healthy for a given height, they are considered overweight or obese. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an adult with a body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight. An adult with a BMI of 30 or higher is considered obese (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). People who are so overweight that they are at risk for death are classified as morbidly obese, defined as having a BMI over 40 (Figure MO.9).

There is a problem with BMI. Although BMI has been used as a healthy weight indicator by the World Health Organization (WHO), the CDC, and other groups, its value as an assessment tool has been questioned. The BMI is most useful for studying populations, which is the work of these organisations. It is less useful, however, in assessing an individual, since height and weight measurements fail to account for important factors like fitness level. An athlete, for example, may have a high BMI because the tool doesn’t distinguish between the body’s percentage of fat and muscle.

Weight and BMI is not sufficient for diagnosis. BMI is not the best indicator of obesity because it does not differentiate between muscle and fat mass, nor does it consider fat distribution or overall body composition. This can lead to misclassification, where individuals with high muscle mass are labeled as obese, while those with high body fat but normal BMI are overlooked. Thus, relying solely on BMI can result in inaccurate assessments of an individual’s health (Nuttall, 2015). In addition, recent research suggests that Body Mass Index (BMI) might not be the best measure of obesity for people aged 40 and older. BMI is a simple calculation based on height and weight, but it doesn’t tell us how much of a person’s weight is fat versus muscle. As we age, we tend to lose muscle and gain fat, which BMI doesn’t account for. A study found that using a BMI of 27, instead of the traditional 30, more accurately identified middle-aged and older adults with obesity (McCall, 2024). This is important because excess body fat, rather than just high body weight, is linked to higher risks of diseases like diabetes and heart disease. For a more accurate assessment of obesity in older adults, therefore, considering body fat percentage and using additional measures like waist circumference can be more effective.

Health Risks

Being extremely overweight or obese is a risk factor for several negative health consequences, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes, liver disease, sleep apnea, various cancers, infertility, and arthritis (Roever-Borges & Resende Es, 2015; Poirier et al., 2006; George et al., 2021; Safdar et al., 2003). Being overweight and/or obese are significant health concerns in Canada, with a large portion of the adult population affected (Kolahdooz et al., 2017; Reid & Hoens, 2012).

Environmental Factors and Lifestyle

Environmental factors, such as living in impoverished, crime-ridden neighbourhoods or having limited access to nutritious food, can contribute to obesity. Understanding the causes of being overweight and/or obese involves considering a mix of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Typically, consuming more calories than burned leads to fat storage.

Treatment Approaches

Typically, individuals who are overweight or obese are advised to reduce their weight through diet and exercise. While some achieve significant success with these methods, many find it challenging to lose excess weight. In situations where an individual has not succeeded with repeated weight reduction attempts or faces a risk of death due to obesity, bariatric surgery may be considered. This type of surgery, aimed specifically at weight reduction, involves altering the gastrointestinal system to limit food intake and/or absorption (Mayo Clinic, 2013). A recent meta-analysis indicates that bariatric surgery is more effective than non-surgical treatments for obesity in the first two years following the procedure, although long-term studies are not yet available (Gloy et al., 2013).

Talking about obesity in a chapter on motivation is important because it shows us that being overweight isn’t just about personal choices. It’s also about the world we live in: what food is available, how our communities are built, and what we see in the media. This section tells us that blaming people for being overweight is too simple. Instead, we should look at all the things that influence someone’s weight, including their genetics, surroundings and lifestyle. By understanding this bigger picture, we can see how making healthier choices isn’t just up to one person. It’s about everyone working together to make it easier to choose good food and stay active. This way, when we talk about motivation, we’re not just asking people to try harder. We’re also talking about how society can help everyone make better choices for their health.

Eating Disorders: Causes and Motivation to Overeat or Not Eat

Eating Disorder Scientific Terms

- Anorexia Nervosa: A condition where someone doesn’t eat enough because they see themselves as overweight even if they’re very thin. They are scared of gaining weight and can go to extreme lengths to lose more weight, which can be very harmful to their health.

- Bulimia Nervosa: A condition where someone eats a lot of food in a short time (bingeing) and then tries to get rid of the food or calories (purging) by making themselves vomit, using laxatives, or exercising a lot. This cycle can be harmful to their physical and mental health.

- Binge-Eating Disorder: A condition where someone frequently eats large amounts of food in a short period and feels unable to stop or control their eating. Unlike bulimia, they don’t regularly purge after eating, but they might feel guilty or ashamed afterward.

- Body Dysmorphia: When someone is very focused on and worried about a flaw in their appearance that might be minor or not noticeable to others. This can make them feel very unhappy and anxious about how they look.

- Compensatory Behaviours: Actions someone takes to try to make up for or undo something they feel guilty about, like eating too much. In eating disorders, this can mean exercising a lot or making oneself vomit after eating.

- Coping Mechanism: The ways in which someone deals with difficult situations or emotions. Eating a lot or not eating at all can be ways some people try to handle stress, sadness, or other tough feelings.

Eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, present complex challenges to our understanding of motivation, particularly the motivation to not eat. Contrary to the perception that eating disorders solely result in underweight conditions, research shows that individuals across a spectrum of body weights can experience these disorders, with significant medical and psychological consequences (Swenne, 2016; Nagata et al., 2018; McCuen‐Wurst et al., 2018).

The motivation to not eat, especially in disorders like anorexia nervosa, often stems from a distorted body image and an intense fear of gaining weight, leading individuals to restrict food intake severely (Mayo Clinic, 2012a). Not merely a personal failing, this fear is influenced by broader societal pressures and cultural norms that idealise thinness, contributing to the development of eating disorders (Smink et al., 2012; Collier & Treasure, 2004).

In bulimia nervosa, the cycle of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviours such as purging or excessive exercise reflects a complex interplay of motivations. While individuals may engage in binge eating as a coping mechanism for emotional distress, the subsequent guilt and fear of weight gain can motivate behaviours aimed at undoing the perceived “damage” of binge eating (Mayo Clinic, 2012b).

Binge-eating disorder highlights a different aspect of the motivation to not eat, where the distress following binge episodes can lead to periods of food restriction in an attempt to control weight, despite the absence of compensatory behaviours (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

These disorders underscore a critical point: the motivation to not eat is deeply intertwined with psychological, social, and cultural factors. The fear of gaining weight, influenced by societal ideals and personal body image distortions, drives individuals to engage in harmful behaviours. Understanding these motivations is crucial for addressing the root causes of eating disorders and developing effective treatments.

Eating disorders have traditionally been viewed as psychological disorders characterised by abnormal eating habits, and often linked to issues of control and self-esteem. Newer theories expand this view by incorporating the roles of societal pressures and gender norms. Malson and Burns (2009) suggest that eating disorders should be understood in the context of cultural norms around body image and the societal expectations placed on women. Young women in our society are inundated with images of extremely thin models (sometimes accurately depicted and sometimes digitally altered to make them look even thinner). This perspective highlights how cultural pressures to conform to certain body standards can contribute to the development of eating disorders. Additionally, feminist theories advocate for a more detailed understanding of eating disorders that goes beyond individual pathology and considers the broader social and cultural dynamics at play (Colăcel, 2016).

Conclusion

The motivation to not eat, as seen in eating disorders, challenges our understanding of motivation as solely driven by physiological needs. It highlights the powerful influence of psychological factors, societal pressures, and cultural norms on our behaviours. Recognising and addressing these influences is essential in treating eating disorders and supporting individuals in achieving a healthier relationship with food and their bodies.

What Do Metabolism and Body Weight Have to Do with Motivation?

- Biological Basis of Motivation: Understanding metabolism and body weight provides insight into the biological underpinnings of motivation. The body’s need to maintain energy balance influences our behaviours and choices, driving us to seek food when energy is needed and to stop eating when the energy requirement is met. This biological motivation is fundamental to survival, and influences daily decisions about food and activity levels.

- Impact of Environmental and Psychological Factors: While metabolism and body weight are influenced by biological factors, they are also significantly affected by environmental and psychological factors. For example, access to food, societal norms, and emotional states can all motivate eating behaviours that may not align with biological needs. Recognising these influences can help individuals make more informed choices about their health and well-being.

- Health Motivation: The distinction between “normal weight” and “healthy weight” underscores the importance of aiming for a weight that minimises health risks rather than conforming to societal or statistical norms. This shift in focus can motivate individuals to adopt healthier eating and exercise habits for long-term health benefits rather than short-term aesthetic goals.

- Understanding and Challenging Theories: Theories like the set-point theory and the settling point model offer frameworks for understanding how body weight is regulated and how individuals can be motivated to maintain a healthy weight. Discussing these theories can challenge simplistic notions of willpower and highlight the complex interactions of factors that motivate our eating and exercise behaviours.

Weight Bias Discrimination

Weight bias discrimination or weight stigma refers to the negative attitudes and behaviours directed at individuals because of their weight. This kind of stigma can worsen health issues and increase emotional distress, impacting a person’s life severely (World Health Organization, 2021; Puhl & Heuer, 2009; Tomiyama et al., 2018). Weight bias is common in healthcare, workplaces, and even within families. It can lead to poorer healthcare for obese patients (Phelan et al., 2015), increased stress, weight gain, and decreased motivation for physical activities (Hunger et al., 2015; Tomiyama et al., 2018). Experiencing or internalising weight bias can lead to lower self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and various psychological disorders (Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Durso & Latner, 2008). Perceived weight discrimination has also been linked to weight gain (Jackson, Beeken, & Wardle, 2015). It is crucial to address weight bias comprehensively and empathetically when developing effective strategies for obesity management and prevention.

Watch this video: The Very Real Consequences of Weight Discrimination (5 minutes)

“The Very Real Consequences of Weight Discrimination” video by SciShow Psych is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Summary: Hunger and Eating

In this section we examine the relationship between hunger and eating behaviours. In addition, we discover the motivations behind our food choices. First, we examine the physiological mechanisms that drive hunger and satiety, highlighting how these processes influence our motivation to eat.

Then we learn about metabolism and body weight, challenging the notion that “normal weight” equates to “healthy weight”. A comparison of average and healthy weights for Canadian adults is presented, alongside a discussion on how metabolism and body weight relate to motivation, particularly in the context of eating and body dysmorphic disorders.

Obesity and eating disorders are addressed, focusing on the causes and motivations behind excessive eating or the refusal to eat. The section underscores the complexity of these conditions, including the psychological, social, and physiological factors involved.

Image Attributions

Figure MO.8. Figure 10.9 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure MO.9. Figure 10.10 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).