Chapter 10. Intelligence and Language

Individual Differences in Intelligence

Dinesh Ramoo

Approximate reading time: 29 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how very high and very low intelligence is defined and what it means to be highly intelligent or not.

- Explain how intelligence testing can be used to justify political or racist ideologies.

- Define stereotypes and explain how they might influence scores on intelligence tests.

Intelligence is defined by the culture in which it exists. Most people in Western cultures tend to agree with the idea that intelligence is an important personality variable that should be admired in those who have it. People from Eastern cultures tend to place less emphasis on individual intelligence and are more likely to view intelligence as reflecting wisdom and the desire to improve the society as a whole rather than only themselves (Baral & Das, 2004; Sternberg, 2007). In some cultures, it is seen as unfair and prejudicial to argue, even at a scholarly conference, that men and women might have different abilities in domains such as math and science, and that these differences might be caused by context, environment, culture, and genetics. In short, although psychological tests may accurately measure intelligence, a culture interprets the meanings of those tests and determines how people with differing levels of intelligence are treated.

Extremes of intelligence: Extremely low intelligence

One end of the normal distribution of intelligence scores is defined by people with very low IQ. Intellectual disability is the term used to describe those individuals who have an IQ below 70, who have experienced deficits since childhood, and who have trouble with basic life skills, such as dressing and feeding themselves and communicating with others (Switzky & Greenspan, 2006). About 1% of the Canadian population, most of them males, fulfill the criteria for intellectual disability, but some children who are diagnosed as mentally disabled lose the classification as they get older and better learn to function in society. People with low IQ are particularly vulnerable to being taken advantage of by others; this is an important aspect of the definition of intellectual disability (Greenspan, Loughlin, & Black, 2001). Intellectual disability is divided into four categories: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. These are not quantifiable categories; they are described in qualitative terms based on the level of impact they have on daily functioning. Severe and profound intellectual disabilities are usually caused by genetic mutations or accidents during birth, whereas mild forms have both genetic and environmental influences.

One cause of intellectual disability is Down syndrome, a chromosomal disorder caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome. The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at one per 800 to 1,000 births, although its prevalence rises sharply in those born to older mothers (Figure IL.8). People with Down syndrome typically exhibit a distinctive pattern of physical features, including a flat nose, upwardly slanted eyes, a protruding tongue, and a short neck.

Societal attitudes toward individuals with intellectual disabilities have changed over the past decades. We no longer use terms such as moron, idiot, or imbecile to describe these people, although these were the official psychological terms used to describe degrees of intellectual disability in the past. Laws, such as the Canadians with Disabilities Act, have made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of mental and physical disability, and there has been a trend to bring the intellectually disabled out of institutions and into our workplaces and schools.

Extremes of intelligence: Extremely high intelligence

Having extremely high IQ can be just as problematic as having extremely low IQ. It is often assumed that school children who are labelled as gifted may have adjustment problems that make it more difficult for them to create social relationships. To study gifted children, Lewis Terman and Melita Oden (1959) selected about 1,500 high school students who scored in the top 1% on the Stanford-Binet and similar IQ tests (i.e., who had IQs of about 135 or higher), and tracked them for more than seven decades; the children became known as the “termites” (named after Lewis Terman) and are still being studied today. This study found, first, that these students were not unhealthy or poorly adjusted but rather were above average in physical health and were taller and heavier than individuals in the general population. The students also had above average social relationships — for instance, being less likely to divorce than the average person (Seagoe, 1975).

Terman’s study also found that many of these students went on to achieve high levels of education and entered prestigious professions, including medicine, law, and science. Of the sample, 7% earned doctoral degrees, 4% earned medical degrees, and 6% earned law degrees. These numbers are all considerably higher than what would have been expected from a more general population. Another study of young adolescents who had even higher IQs found that these students ended up attending graduate school at a rate more than 50 times higher than that of the general population (Lubinski & Benbow, 2006).

As you might expect based on our discussion of intelligence, children who are gifted have higher scores on general intelligence (g), but there are also different types of giftedness. Some children are particularly good at math or science, some at automobile repair or carpentry, some at music or art, some at sports or leadership, and so on. There is a lively debate among scholars about whether it is appropriate or beneficial to label some children as gifted and talented in school and to provide them with accelerated special classes and other programs that are not available to everyone. Although doing so may help the gifted kids (Colangelo & Assouline, 2009), it also may isolate them from their peers and make such provisions unavailable to those who are not classified as gifted.

Sex Differences in Intelligence

The introduction to this chapter addresses Lawrence Summers’s assertion regarding the underrepresentation of women in the hard sciences. His claim partially rests on the belief that environmental factors, like gender discrimination or societal norms, play a significant role. He also considers the possibility that genetic differences may render women less capable of certain tasks compared to men. These claims, and the responses they provoked, provide another example of how cultural interpretations of the meanings of IQ can create disagreements and even guide public policy.

Assumptions about sex differences in intelligence are increasingly challenged in the research. In Canada, recent statistics show that women outnumber men in university degrees earned. People with university degrees generally tend to score higher on IQ tests (but remember that scoring high on an IQ test is not the same as being highly intelligent). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published its Education at a Glance 2013 report, which showed Canada leading 34 OECD countries in the proportion of adults who have completed a tertiary (post-secondary) education. It reported that in 2011, 51% of Canadian adults aged 25 to 64 had attained a post-secondary education (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2013). Additionally, the report highlighted the fact that Canadian women had significantly higher rates of tertiary education attainment than men, with 56% of women versus 46% of men, marking a 16 percentage-point disparity between genders among the younger adult population.

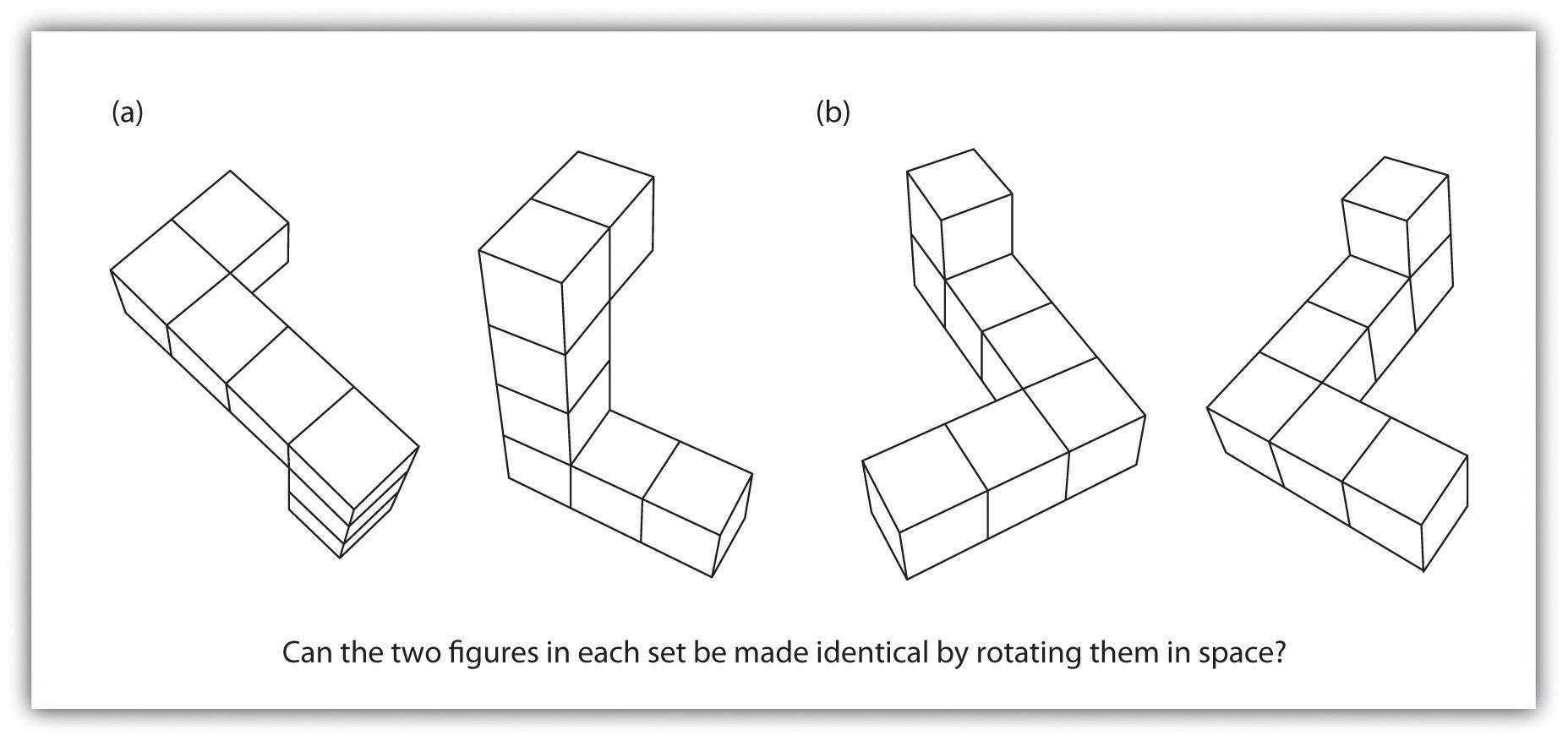

There are also observed sex differences on some particular types of tasks. Women tend to do better than men on some verbal tasks, including spelling, writing, and pronouncing words (Halpern et al., 2007); they also have better emotional intelligence, in the sense that they are better at detecting and recognising the emotions of others (McClure, 2000). On average, men do better than women on tasks requiring spatial ability (Voyer, Voyer, & Bryden, 1995), such as the mental rotation tasks (Figure IL.9). Boys tend to do better than girls on both geography and geometry tasks (Vogel, 1996).

Although these differences are real, and can be important, keep in mind that like virtually all sex-group differences, the average difference between men and women is small compared with the average differences within each sex (Lynn & Irwing, 2004). There are many women who are better than the average man on spatial tasks, and many men who score higher than the average woman in terms of emotional intelligence. Sex differences in intelligence allow us to make statements only about average differences and do not say much about any individual person. Social influences may also play a role in terms of the academic disciplines or areas in which boys and girls show an early interest. This, in turn, may influence their performance on IQ tests.

The origins of sex differences in intelligence are not clear. Differences between men and women may be in part genetically determined, perhaps by differences in brain lateralisation or by hormones (Kimura & Hampson, 1994; Voyer, Voyer, & Bryden, 1995), but nurture is also likely important (Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2006). As infants, boys and girls show no or few differences in spatial or counting abilities, suggesting that the differences occur at least in part as a result of socialisation (Spelke, 2005). Furthermore, the number of women entering the hard sciences has been increasing steadily over the past years, again suggesting that some of the differences may have been due to gender discrimination and societal expectations about the appropriate roles and skills of women.

Racial Differences in Intelligence

One of the most controversial and divisive areas of research in psychology has been to look for evidence of racial differences in intelligence (e.g., Lynn & Vanhanen, 2002; 2006). Firstly, the concept of race as a biological category is problematic. Things like skin colour and facial features might define social or cultural conceptions of race but are biologically not very meaningful (Chou, 2017; Yudell, 2014). Secondly, intelligence interacts with a host of factors such as socioeconomic status and health; factors that are also related to race. Wealth in North America has traditionally been linked to land ownership. European settlers were originally given land to settle, which could then be sold or used as collateral to acquire loans. On the other hand, Indigenous Peoples were deprived of their land, and other ethnic minorities (such as Black Americans) were not given the same land rights as European settlers. Later developments that allowed people to get government-backed mortgages were also systematically denied to minorities. This history explains the wide wealth disparity between white people and other races, which in turn influences IQ test performance. Thirdly, intelligence tests themselves may be worded or administered in ways that favour the experiences of some groups (e.g., white Americans), thus maximising their scores, while failing to represent the experiences of other groups (e.g., Black Americans), thus lowering their scores.

In the United States, differences in the average scores of white and Black Americans have been found consistently. For several decades, the source of this difference has been contentious, with some arguing that it must be genetic (e.g., Reich, 2018) while others argue that it is nothing of the sort (e.g., Turkheimer, Harden, & Nisbett, 2017). Interestingly, this debate among scholars is playing out in a nontraditional manner; as well as in scholarly journals, the debate has become more widely accessible due to the use of social and online media.

When average differences in intelligence have been observed between groups, these observations have, at times, led to discriminatory treatment of people from different races, ethnicities, and nationalities (Lewontin, Rose, & Kamin, 1984). One of the most horrifying examples was the spread of eugenics, the proposal that one could improve the human species by encouraging or permitting reproduction of only those people with genetic characteristics judged desirable. This was broadly understood as white Europeans versus other ethnicities. However, even within white populations, eugenicists advocated for restricted reproduction rights for poor people as they considered poverty being a consequence of some perceived biological characteristics.

Intelligence Testing and the Eugenics Movement

In the first half of the 20th century, many psychologists, along with huge numbers of other influential people in society, including President Roosevelt, embraced the horrific field of eugenics. The eugenics movement was founded by an English scientist called Francis Galton, who misappropriated Charles Darwin’s work on evolution and Gregor Mendel’s work on heritable traits in plants and animals, by arguing that these ideas could be extended to human traits. Eugenicists believed that genes, not environment, determined intelligence (among other traits), and that people with low intelligence should be prevented from “spreading their genes”. These beliefs were extremely widespread across Europe and the United States (US). Many of the Western psychologists involved in developing intelligence tests were eugenicists, including Spearman in the UK, and Terman in the US. As a result, intelligence testing was weaponized as evidence of low intelligence among people with little formal education. This included women, people of colour, and people living in poverty (Guthrie, 1998). Eugenics was used to promote and justify social and economic inequalities in the US, the United Kingdom, and the countries that they colonized. The long-term consequences of eugenics-inspired oppressive socioeconomic policies still persist today.

In addition to his eugenicist beliefs, Spearman (1904) also popularised the idea that intelligence could be adequately measured by a single score that represented a person’s general intelligence (Boake, 2002; Guthrie, 1998). Spearman justified this approach because he had found that people who were proficient in one intellectual domain, e.g., verbal skills, were often equally adept in other domains, such as quantitative reasoning (Biswas-Diener, 2018; Guthrie, 1998).

In the 1940s, Raymond Cattell proposed that intelligence consists of two major factors: crystallised intelligence and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963). Crystallised intelligence is characterised as the ability to retrieve knowledge related to your educational and life experiences. When you learn, remember, and recall information in your classes, you are using crystallised intelligence. Fluid intelligence on the other hand, encompasses the ability to cope with new situations, see complex relationships, and solve abstract problems (Cattell, 1963). More recent theories suggest that intelligence consists of multiple different domains that go beyond cognitive skills; a person may be strong in one, but not others (Gardner, 1983; Sternberg 1999). The first widely used intelligence test in the US was designed to measure general intelligence, and so minimised the strengths of people who were not good “all-rounders”. The test was developed in 1916 by Lewis Terman, a eugenicist and a professor at Stanford University. Terman adapted the Binet-Simon Scale for use in the US and renamed it the Stanford-Binet scale. Scores on the Stanford-Binet scale were referred to as the intelligence quotient or IQ (Guthrie, 1998). Terman standardised the Stanford-Binet scale using data from 1000 children and 400 adults in the US (Guthrie, 1998), all of whom were white.

Standardisation is a commonly used procedure when developing psychological tests. Raw scores are converted so that they fall in a normal distribution, which is shaped like a “bell curve” to allow for easy comparisons between individuals (Biswas-Diener, 2018). It is therefore important that the scores are standardised using a large sample of people who are representative of the population. In the Stanford-Binet (and other subsequent IQ tests) the mean IQ score is set at 100. In the standardised sample, 68% of people have an IQ between 85 and 115, and 96% of people have an IQ of between 70 and 130. There are very few people at the extremes of the scale. You probably have taken at least one standardised aptitude test (like the SAT) in your life. The scores on these tests are standardised in a similar way, but the average score is set around 500 on each SAT subtest.

Excluding people of colour from the standardisation process was a serious flaw in Terman’s Stanford-Binet intelligence test, as the standardised scores were not representative of the population (Guthrie, 1998). The test relied heavily on verbal skills and asked questions that reflected middle-class values, so children with little schooling were often misclassified as having low intelligence. The same issues that made the Stanford-Binet test culturally unfair for less educated children also plagued the adult intelligence tests that were developed for the army during the First World War (Guthrie, 1998).

In 1917, Yerkes (another eugenicist), Terman, and other psychologists from the American Psychological Association helped to design intelligence tests for the US army. These were used to determine work assignments for army recruits (Guthrie, 1998). Not only were the tests culturally biased, but the military psychologists who administered them were all white men; many of them were blatantly racist, which probably influenced their scoring (Guthrie, 1998). The army then released reports based on the test scores, stating that non-whites, Jews, and Eastern and Southern European immigrants were intellectually inferior to whites. Moreover, they reported that people with darker skins were less intelligent than light-skinned people (Guthrie, 1998). This misguided report was widely disseminated and was used to further justify and promote many harmful socioeconomic policies. In the US, interracial marriages were banned, and racial segregation was strongly enforced, to decrease the potential development of inter-racial relationships. Policies such as redlining (a discriminatory practice in which financial services are withheld from neighbourhoods that have significant numbers of racial and ethnic minorities) and racially segregating schools, increased wealth and resources for whites and reduced economic opportunities and educational resources for people of colour. The 1924 Immigration law severely restricted the admittance of Jews, Eastern and Southern Europeans, and people who were mentally ill, to the United States (Guthrie, 1998).

In keeping with eugenicist ideals, by 1944 40,000 people had been subjected to forced sterilisation in the United States, and 30 states had passed laws legalising this practice. Forced sterilisation targeted mostly poor Black women and immigrants and included people living in institutions for the mentally ill, people accused of crimes, and people with disabilities or chronic illnesses. Scandinavia and Canada also embraced forced sterilisation during the same general time period (Kevles, 1999). Adolf Hitler and other German eugenicists were inspired by the widespread ways that the US embraced white supremacy through its sterilisation and immigration laws. However, the policies that Germany subsequently created were even more extreme; they mandated killing young children with physical or mental disabilities. Eugenics was also used to justify the persecution and mass murders of six million Jews during the Holocaust (Guthrie, 1998). Sterilisations in the United States declined dramatically in the aftermath of the atrocities of the Holocaust and in the light of new studies showing that intelligence and mental illness are not solely determined by genes. However, even as laws began to change, the US still carried out about 22,000 more forced sterilisations across 27 states between 1943 and 1963. Some of these sterilisations occurred in some southern and mid-Western states shortly after World War II, when reproductive clinics began offering sterilisation as a method of birth control to young, mostly Black, poor women in rural areas, and to young native American women. Many of these sterilisations were coerced or done without the woman’s consent (Reilly, 2015). It was not until the 60s and 70s that US sterilization laws were largely repealed (Sofair & Kaldjian, 2000; Suarez-Balcazar, 2022). However, reproductive injustice continues even today. In 2020, a nurse working for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) made it publicly known that several Latina women were coerced into having unnecessary hysterectomies during their detention by ICE (Suarez-Balcazar, 2022).

Eugenics became popular in Canada and the United States in the early 20th century and was supported by many prominent psychologists, including Sir Francis Galton (1822–1911). Dozens of universities offered courses in eugenics, and the topic was presented in most high school and university biology texts (Selden, 1999). Belief in the policies of eugenics led the Canadian legislatures in Alberta (1928) and British Columbia (1933) to pass sterilisation laws that led to the forced sterilisation of approximately 5000 people deemed to be “unfit.” Those affected were mainly youth and women, and people of Indigenous or Metis identity were disproportionately targeted. This practice continued for several decades before being completely abandoned and the laws repealed. This dark chapter in Canadian history shows how intelligence testing has been used to justify political and racist ideologies.

Research Focus

Stereotype threat

Although intelligence tests may not be culturally biased, the situation in which one takes a test may be. One environmental factor that may affect how individuals perform and achieve is their expectations about their ability at a task. In some cases, these beliefs may be positive, having the effect of making us feel more confident and thus better able to perform tasks. For instance, research has found that because Asian students are aware of the cultural stereotype that “Asians are good at math”, reminding them of this fact before they take a difficult math test can improve their performance on the test (Walton & Cohen, 2003).

On the other hand, sometimes these beliefs are negative and create negative self-fulfilling prophecies, leading to poorer performance just because of our knowledge about the stereotypes. Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson (1995) tested the hypothesis that the differences in performance on IQ tests between Black and white Americans might be due to the activation of negative stereotypes. Because Black students are aware of the stereotype that Blacks are intellectually inferior to whites, this stereotype might create a negative expectation, which might interfere with their performance on intellectual tests through fear of confirming that stereotype.

The experiments supported the hypothesis by showing that Black university students’ performance on standardised test questions declined compared to their previous scores when the task was presented as an assessment of their verbal abilities, thereby making the stereotype pertinent. Their performance, however, was not influenced when the same questions were described as an exercise in problem-solving. In another study, the researchers found that when Black students were asked to indicate their race before they took a math test, again activating the stereotype, they performed more poorly than they had on prior exams, whereas white students were not affected by first indicating their race.

Researchers concluded that thinking about negative stereotypes that are relevant to a task that one is performing creates stereotype threat, i.e., it creates performance decrements caused by the knowledge of cultural stereotypes. They argued that the negative impact of race on standardised tests may be caused, at least in part, by the performance situation itself.

Research has found that stereotype threat effects can help explain a wide variety of performance decrements among those who are targeted by negative stereotypes. When stereotypes are activated, children with low socioeconomic status perform more poorly in math than do those with high socioeconomic status, and psychology students perform more poorly than do natural science students (Brown, Croizet, Bohner, Fournet, & Payne, 2003; Croizet & Claire, 1998). Even groups who typically enjoy advantaged social status can be made to experience stereotype threat. For example, white men perform more poorly on a math test when they are told that their performance will be compared with that of Asian men (Aronson, Lustina, Good, Keough, & Steele, 1999), and whites perform more poorly than Blacks on a sport-related task when it is described to them as measuring their natural athletic ability (Stone, 2002; Stone, Lynch, Sjomeling, & Darley, 1999).

Research has found that stereotype threat is caused by both cognitive and emotional factors (Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008). On the cognitive side, individuals who are experiencing stereotype threat show an increased vigilance toward the environment as well as increased attempts to suppress stereotypic thoughts. Engaging in these behaviours takes cognitive capacity away from the task. On the affective side, stereotype threat occurs when there is a discrepancy between our positive concept of our own skills and abilities and the negative stereotypes that suggest poor performance. These discrepancies create stress and anxiety, and these emotions make it harder to perform well on the task.

Stereotype threat is not, however, absolute; we can get past it if we try. What is important is to reduce the anxieties that are activated when we consider the negative stereotypes. Manipulations that affirm positive characteristics about the self or one’s social group are successful at reducing stereotype threat (Marx & Roman, 2002; McIntyre, Paulson, & Lord, 2003). In fact, just knowing that stereotype threat exists and may influence our performance can help alleviate its negative impact (Johns, Schmader, & Martens, 2005).

In summary, although there is no definitive answer to why IQ bell curves differ across racial and ethnic groups, and most experts believe that environment is important in pushing the bell curves (normal distribution) apart, genetics can also be involved. It is important to realise that although IQ is heritable, this does not mean that group differences are caused by genetics. Although some people are naturally taller than others, since height is heritable, people who get plenty of nutritious food are taller than people who do not, and this difference is clearly due to environment. This is a reminder that group differences may be created by environmental variables but the size of the difference can be reduced through appropriate environmental actions such as equitable educational and training programs.

Image Attributions

Figure IL.8. The Down Syndrome Association of Central Florida’s Step Up for Down Syndrome by Rich Johnson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

Figure IL.9. Figure 9.8 is adapted from Halpern, et al. (2007), found in Introduction to Psychology, and shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Jorden A. Cummings via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).