Chapter 15. Psychology in Our Social Lives

Interacting with Others

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate Reading Time: 26 minutes

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you will be able to:

- Appreciate the importance of affiliation and altruism

- Explain the causes of human aggression

As humans, we’ve gained a range of social skills that help us connect with others effectively. Building connections with people, forming relationships, is a crucial part of our lives. We naturally tend to be supportive and lend a helping hand, even when it means making sacrifices for ourselves. However, there are times when we might find ourselves in situations where aggression becomes a response, depending on the circumstances. In this chapter, we’ll explore these aspects — relationships, helping, and aggression — to better understand the dynamics of interacting with others.

Forming Relationships

One of the most important tasks faced by humans is to develop successful relationships with others. These relationships can be casual, like acquaintanceships and friendships. They can also be more serious, like long-term intimate and romantic relationships, such as in a marriage. It is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving.

One important factor is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). Similarity is important for relationships, both because it is more convenient (e.g., it’s easier if both partners like to ski or go to the movies than if only one does) and because similarity supports our values (e.g., I can feel better about myself and my choice of activities if I see that you also enjoy doing the same things that I do).

Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, which is the tendency to communicate frequently without worrying about getting into trouble, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen to and respond to our needs. When the partners in a relationship feel that they are close, and when they indicate that the relationship is based on caring, warmth, acceptance, and social support, we can say that the relationship is intimate (Reis & Aron, 2008). For the relationship to endure, self-disclosure must be reciprocal. If I open up to you about the concerns that are important to me, I expect you to do the same in return.

Another important determinant of liking is proximity, which is the extent to which people are physically near us. You are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, such as those who live in your dorm, or those who just happen to sit nearer to you in the classrooms (Back et al., 2008).

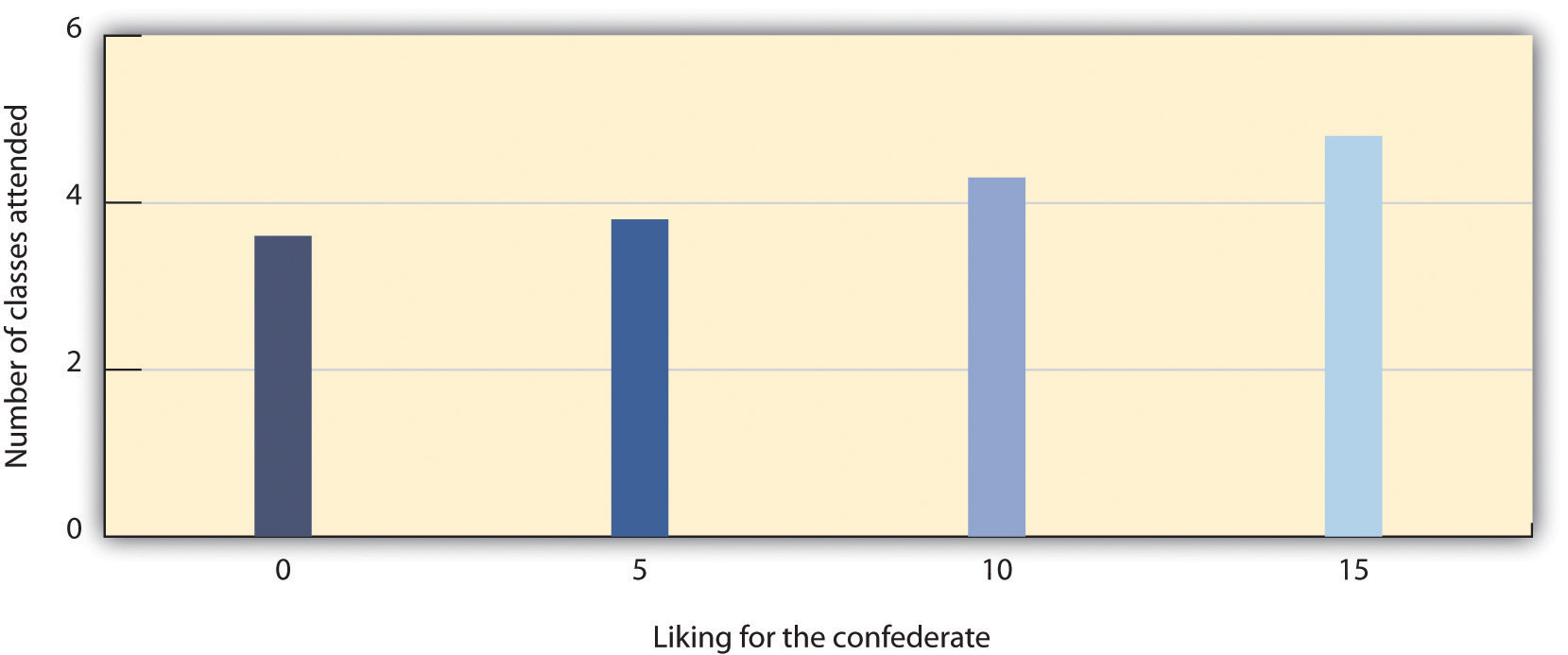

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure — the tendency to prefer stimuli (e.g., a person or an object) that we have seen more frequently. Richard Moreland and Scott Beach (1992) studied mere exposure by having female confederates attend a large lecture class of over 100 students 0, 5, 10, or 15 times during a semester. At the end of the term, the other students in the class were shown pictures of the confederates and asked to indicate both if they recognised them and also how much they liked them. The number of times the confederates had attended class did not influence the other students’ ability to recognise them, but it did influence their liking for them.

The effect of mere exposure is powerful in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981). People like mirror-image pictures of their faces more than the direct image that others see, but their friends prefer non-mirror-image pictures (Mita et al., 1977). This happens because people are used to seeing their own face in a mirror.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an innate fear of the unknown, but as things become more familiar, they seem less threatening and dangerous (Freitas et al., 2005), and thus produce more positive affect (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001). In addition, familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Leslie Zebrowitz and colleagues (2007) point out that we like people of our own racial group, in part because we perceive them as similar to us.

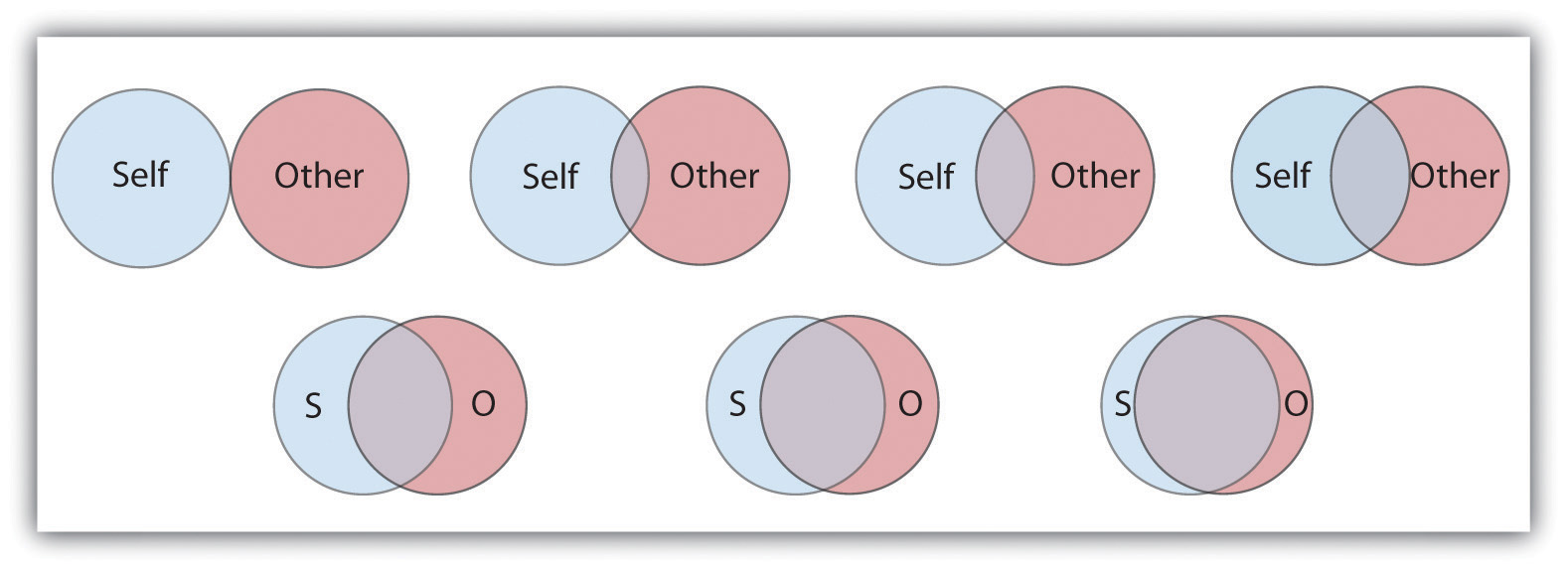

In the most successful relationships, the two people begin to see themselves as a single unit. Arthur Aron and colleagues (1992) assessed the role of closeness in relationships using the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (Figure SL.18). You can take this measure yourself for some different people that you know, like your family members, friends, or significant other. The measure is simple to interpret. If the circles that show you and the other person overlap a lot, it means your relationship is close. But if the circles have less overlap, it means your relationship is not as close. Although this closeness measure is very simple, Aron and colleagues (1991, 1995) discovered that it can predict people’s satisfaction with their close relationships and couples’ tendency to stay together.

Sometimes intimacy lies in the growing interdependence between partners as they navigate shared responsibilities in managing a household, raising children, and caring for elderly parents. The partners increasingly turn to each other for help in coordinating activities, remembering dates and appointments, and accomplishing tasks. Relationships are close, in part, because the couple becomes highly interdependent, relying on each other to meet important goals. In relationships where partners get along well, they naturally feel committed to each other. Commitment refers to the feelings and actions that keep partners working together to maintain the relationship. Partners who are really committed to each other are less interested in other people as possible partners (Lydon et al., 1999). According to Margaret Clark and Edward Lemay (2010), a crucial factor in successful relationships is a sense of responsiveness — knowing that the other person understands, validates, and cares for them. This mutual and unconditional exchange of love promotes the well-being of both partners and creates a secure foundation for their growth and happiness together.

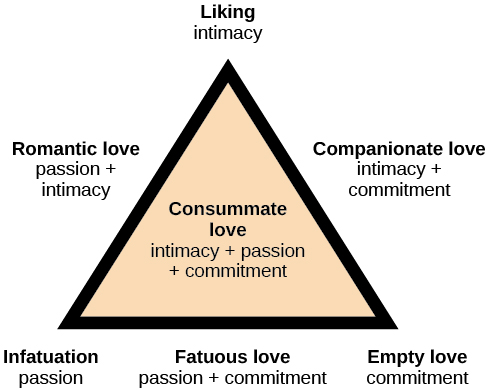

Robert Sternberg (1986) proposed that there are three components of love: intimacy, passion, and commitment. These three components form a triangle that defines multiple types of love: this is known as the triangular theory of love. Intimacy is the sharing of details and intimate thoughts and emotions. Passion is the physical attraction — the flame in the fire. Commitment is standing by the person — the “in sickness and health” part of the relationship. Sternberg (1986) states that a healthy relationship will have all three components of love — intimacy, passion, and commitment — which is described as consummate love. However, different aspects of love might be more prevalent at different life stages. Other forms of love include liking, which is defined as having intimacy but no passion or commitment. Infatuation is the presence of passion without intimacy or commitment. Empty love is having commitment without intimacy or passion. Companionate love, which is characteristic of close friendships and family relationships, consists of intimacy and commitment but no passion. Romantic love is defined by having passion and intimacy, but no commitment. Finally, fatuous love is defined by having passion and commitment, but no intimacy, such as a long-term sexual love affair. Can you think of examples of relationships that fit these different types of love?

People are sometimes motivated to maximise the benefits and minimise the costs of relationships. According to social exchange theory, we act as naïve economists in keeping a tally of the ratio of costs and benefits of forming and maintaining a relationship with others (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). When deciding to commit to a romantic relationship, you likely weighed the benefits and costs of your choice. What are the benefits of being in a committed romantic relationship? You might have considered companionship, intimacy, and passion, along with the comfort of being with someone you know well. What are the costs of being in a committed romantic relationship? You might worry about potential boredom over time from being with only one person, and there could be expenses for shared activities like going to movies and having dinner. However, as long as the benefits of being with your romantic partner outweigh the costs, you will continue the relationship.

Helping Others

Altruism helps create harmonious relationships. Altruism means doing things to make someone else’s life better, especially when you don’t get something for yourself in return. It’s like when we help a person in need on the highway, volunteer at a homeless shelter, or give to a charity. In Canada, 79% of people aged 15 and older volunteered (Statistics Canada, 2018). There are a variety of explanations for why we help. Table SL.4 summarises some of the variables that are known to increase helping.

| Variable | Effect |

|---|---|

| Mood | We help more when we are in a good mood (Guéguen & De Gail, 2003). We may also help in order to reduce our negative feelings caused by other people’s sufferings (Cialdini et al.,1973). |

| Similarity

|

We help people whom we see as similar to us, e.g., those who mimic our behaviours (van Baaren et al., 2004). |

| Empathy | We help more when we feel empathy for the other person (Batson et al., 1983). |

| Responsibility | We are more likely to help when we assume a responsibility to help (Markey, 2000). |

| Self-esteem | We are more likely to help if we can feel good about ourselves by doing so (Snyder et al., 2004). |

| Reputation | We may help in order to show others that we are good people (Hardy and Van Vugt, 2006). |

The tendency to help others in need is an evolutionary adaptation. Although helping others can be costly to us as individuals, helping people who are related to us can help to pass on our own genes (Madsen et al., 2007; Stewart-Williams, 2007). Eugene Burnstein and colleagues (1994) found that students indicated they would be more likely to help a person who was closely related to them (e.g., a sibling, parent, or child) than they would be to help a person who was more distantly related (e.g., a niece, nephew, uncle, or grandmother). People are more likely to donate kidneys to relatives than to strangers (Borgida et al., 1992). Even children indicate that they are more likely to help their siblings than they are to help a friend (Tisak & Tisak, 1996).

Why would we help people to whom we are not related? One explanation is based on the reciprocity norm. On one side, we often help people who have helped us (Whatley et al., 1999); on the flip side, we also expect that those we’ve helped will be there for us in the future. The reciprocity norm is found in everyday adages such as “Scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours” as well as in the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” When we help each other, it boosts our chances of survival and reproduction. Over the course of evolution, those who help and expect help in return tend to have more opportunities to reproduce than those who don’t, thus enabling this kind of altruism to continue.

We also learn to help through reinforcement and modelling. Sandi Smith and colleagues (2006) found that 73% of TV shows had some altruism and that about three altruistic behaviours were shown every hour. The prevalence of altruism was particularly high in children’s shows. We are more likely to help when we receive rewards for doing so and less likely to help when helping is costly. For example, parents praise their children who share their toys with others. A potential reward is the status we gain as a result of helping. When we act altruistically, we gain a reputation as a person with high status who is able and willing to help others, and this status makes us more desirable in the eyes of others (Hardy & Van Vugt, 2006).

Helping based on the reciprocity norm and reinforcement might not seem like true altruism. We might hope that our children adopt a different social norm that feels more genuinely altruistic: the social responsibility norm. The social responsibility norm tells us that we should help others who need it, even without expecting anything in return. Many religions teach this norm, emphasising that as good human beings, we should lend a hand to others whenever we can.

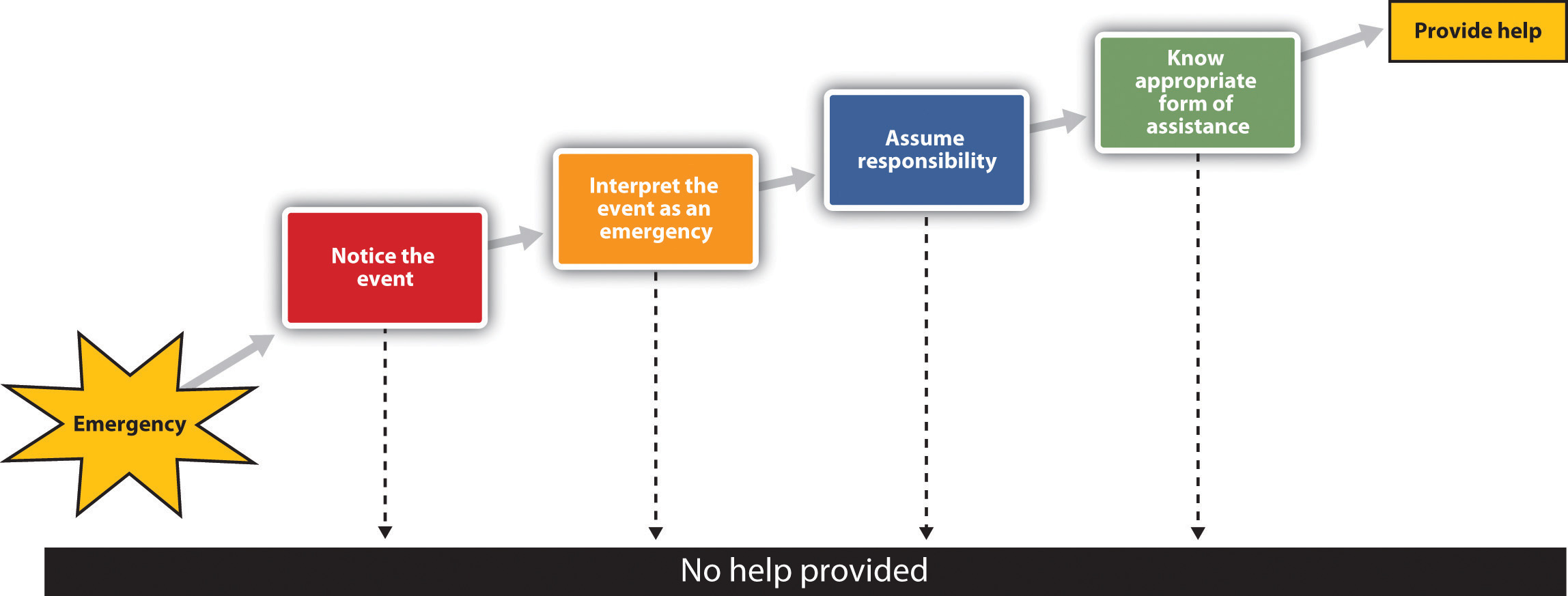

Two social psychologists, John Darley and Bibb Latané (1968), studied the bystander effect — what makes people choose not to help in the presence of others. They created a model that considered how the social situation plays a crucial role in deciding whether people choose to help or not. Many studies have tested this model, and there is strong evidence supporting its validity.

The two prerequisites are noticing the event and interpreting it as an emergency. Latané and Darley (1968) demonstrated the important role of the social situation in noticing the event. They had some people answer questions alone, while others worked in small groups with two more people. After a few minutes, they let white smoke into the room. The researchers timed how long it took for the first person to notice the smoke and call for help.

When people were working alone, they noticed the smoke in about five seconds, and within four minutes, 75% of them took some action. In contrast, in groups, the first person took over 20 seconds on average to notice the smoke. Only 12% of the groups took actions eventually. In 3 out of the 8 groups, no one reported the smoke even after it filled the room. When we are unsure how to interpret an event, we normally look to others to help us understand them, and at the same time, they are looking to us for information. The problem is that each bystander thinks that other people aren’t acting because they don’t see an emergency. Believing that the others know something that they don’t, each observer concludes that help is not required.

Noticing the emergency does not necessarily mean that we will come to the rescue of the person in need. We still need to decide if it is our responsibility to do something. The problem is that when we see others around, it is easy to assume that they are going to do something. Diffusion of responsibility occurs when we assume that others will take action, so we do not take action ourselves. People are more likely to help when they are the only ones in the situation than when there are others around (Darley & Latané, 1968). Have you ever been in an online group where you ask for help? Did you find it easier to get help when you asked one person instead of a lot of people? Patrick Markey (2000) found that people received help more quickly, in about 37 seconds, when they asked for help by specifying a participant’s name than when no name was specified, which took about 51 seconds.

The final factor is knowing how to help. For many of us, the ways to best help another person in an emergency are not that clear. We are not professionals, and we have little training in how to help in emergencies. People who have training in emergencies are more likely to help, while the rest of us might not know what to do and may just walk by. However, nowadays, many people have cell phones, and a quick call can make a big difference.

Aggression

Aggression is behaviour that is intended to harm another individual. Aggression can happen suddenly, like when a jealous person gets really angry or when sports fans cause trouble after a big game. On the other hand, it can also be more deliberate and planned, like a bully taking someone’s toys, a terrorist harming civilians for attention, or a hired assassin killing for money. Not all aggression is physical. Nonphysical aggression includes things like excluding others, calling them names, spreading rumors, or cyberbullying. According to Julie Paquette and Marion Underwood (1999), both boys and girls indicated that nonphysical aggression, like name-calling, made them feel more “sad and bad” compared to physical aggression.

Aggression is often viewed as an adaptive behaviour and part of human nature. Aggression allows us to gain access to valuable resources such as food, territory, and desirable mates, or perhaps to protect ourselves from direct attack by others. If aggression helps in the survival of our genes, then the process of natural selection may well have caused humans, as it would any other animal, to be aggressive (Buss & Duntley, 2006).

One of the primary functions of the amygdala is to help us learn to associate stimuli with the rewards and the punishment that they may provide. The amygdala is particularly activated in our responses to stimuli that we see as threatening and fear-arousing. When the amygdala is stimulated, in either humans or in animals, the organism becomes more aggressive.

The prefrontal cortex serves as a control centre on aggression. When it is more highly activated, we are more able to control our aggressive impulses. Research has found that the cerebral cortex is less active in murderers and death row inmates, suggesting that violent crime may be caused in part by reduced ability to regulate aggression (Davidson et al., 2000).

Hormones are also important in regulating aggression. The male sex hormone testosterone is associated with increased aggression in both males and females (Dabbs et al., 1996). There is a culturally universal tendency for men to be more physically violent than women (Archer & Coyne, 2005). These sex differences do not imply that women are never aggressive. The differences between men and women are smaller after they have been frustrated, insulted, or threatened (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996).

Consuming alcohol increases aggression. Even people who are not normally aggressive may react with aggression when they are intoxicated (Graham et al., 2006). Drinking alcohol makes it harder for people to control their anger. When people are drunk, they become more focused on themselves and less aware of the usual social rules that stop them from acting aggressively (Bushman & Cooper, 1990).

Have you ever felt angry and ended up acting aggressively? It probably happened when you were angry, in a bad mood, tired, in pain, sick, or frustrated. One important determinant of aggression is frustration. When we’re frustrated, we might end up taking out our anger on others, even if they aren’t the ones who caused the frustration. Frustration may arise from social rejection. Research has shown that people who are rejected by others are more likely to act aggressively when provoked (Twenge et al., 2001). Hot weather can make people more aggressive. In a study by William Griffit and Russell Veitch (1971), students filled out surveys in rooms with a regular temperature or ones hotter than 30 degrees Celsius. The students in the hotter rooms showed a lot more hostility. People tend to be more aggressive on hot days compared to cooler days, and this holds true for hot years versus cooler years (Bushman et al., 2005). In addition to high temperature, pain may also trigger aggression (Berkowitz, 1993).

If we’re aware of feeling negative emotions, we might think we could release those feelings in a relatively harmless way, like punching a pillow or kicking something. This act, called catharsis, suggests that engaging in less harmful aggressive actions can release our aggressive tendencies, possibly reducing the likelihood of being aggressive in a more harmful way later. Many considered catharsis as a way to decrease violence. It was a significant part of Sigmund Freud’s theories.

As far as social psychologists have been able to determine, however, catharsis simply does not work. Rather than decreasing aggression, engaging in aggressive behaviours increases the likelihood of later aggression. Brad Bushman and his colleagues (1999) made people in their study upset by having someone insult them. Half of the participants were allowed to engage in a cathartic behaviour: they were given boxing gloves and had a chance to hit a punching bag for two minutes. Then, all the participants played a game with the person who had insulted them earlier. In the game, they had a chance to blast the person with a painful blast of white noise. Contrary to the catharsis hypothesis, the students who had punched the punching bag set a higher noise level and delivered longer bursts of noise than the participants who did not get a chance to hit the punching bag. It seems that if we hit a punching bag, punch a pillow, or scream as loud as we can to release our frustration, the opposite may occur — rather than decreasing aggression, these behaviours in fact increase it.

Research evidence makes it very clear that, on average, people who watch violent behaviour become more aggressive. The evidence supporting this relationship comes from many studies conducted over many years using both correlational designs as well as laboratory studies in which people have been randomly assigned to view either violent or nonviolent material (Anderson et al., 2010). Viewing violent behaviour increases aggression, in part through observational learning. One example is in the studies of Albert Bandura. In his studies, children who witnessed violence were more likely to be aggressive. Continually viewing violence can also lead to desensitization to violence (Bartholow et al., 2006). When we first see violence, we are likely to be shocked, aroused, and even repulsed by it. However, over time, as we see more and more violence, we become habituated to it, such that subsequent exposures produce fewer and fewer negative emotional responses.

Image Attributions

Figure SL.16. From left to right: Photo by Helena Lopes is licensed under the Pexels license; photo by Tim Samuel is licensed under the Pexels license; photo by Steshka Willems is licensed under the Pexels license.

Figure SL.17. Figure 7.4 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure SL.18. Figure 7.5 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure SL.19. Figure 12.28 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License and contains modification of “The three components, labeled on the vertices of a triangle, interact with each other so as to form seven different kinds of love experiences” by “Lnesa” which is in the public domain.

Figure SL.20. Figure 7.8 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).