Chapter 11. Lifespan Development

Lifespan Development Introduction

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 23 minutes

Story Part 1 – Children’s So Called ‘Errors’ and Dr J’s Perspective

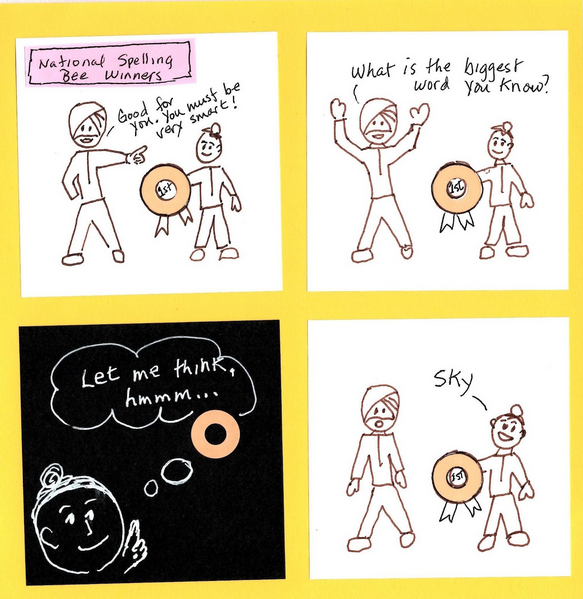

A colleague told me this true story and gave me permission to share it. I have shared it in comic form and changed some details to make it anonymous and protect privacy.

In this opening comic story, an adult wants to connect with a child who has shown great skill in a spelling bee. The adult asks: “What is the biggest word you know?” But what the adult really means is, “What is the longest word you know?” The child interprets the adult’s question as, “What is the biggest thing you know?” This story reveals that the child is in a concrete operational stage of cognition and is not yet ready to imagine the actual question the adult meant to ask. This child responds to the adult’s literal meaning of the question. Guessing what the adult meant to ask would require the cognitive skill of formal operational thinking.

When Jean Piaget observed these apparent ‘mistakes’ or ‘misunderstandings’ that children make, he saw their responses as reflections of the child’s stage of thinking. That is, the child’s responses were not so much “errors” but more like sneak peeks into the workings of the child’s mind at that given point in time and in their development.

Each person in this story reveals the limits of their imagination and the style of their thinking. The adult is clearly surprised by the child’s answer, as they were expecting something different. When we are surprised by another person’s unexpected answer, we have the opportunity to learn just as much about our own minds as theirs.

My take on this story. When we are surprised when ‘children say the cutest things,’ we also learn just as much about our own thinking, the limitations in our imagination, and the shortcomings in our ability to ask precise questions. When we are surprised by what someone says, it is likely that we have our own expectations — or biases — about how the question should be answered. Every time we are surprised by someone’s response, we have an opportunity to think about our own cognitive processes and our preconceived ideas.

In a way, it is a form of “adultism” — or hubris — for us to label the child’s answer as an ‘error’ or ‘misunderstanding’ and not at the same time question our own assumptions, failing to account for lived experiences and individual biases. Personally, I have learned that the greatest joy and biggest reward of being curious and asking many questions is that I can experience wonderful moments of surprise, confusion, and/or hilarity that reveal just as much about the limits or ‘errors’ of my mind as of the person I am in conversation with.

In this story, I find the child’s answer, “sky”, to be mystical and wise. Brilliant! A true ‘mic drop’ answer. I am grateful that I was given permission to share this story with you. Now, it is your turn to look at lifespan development with a fresh perspective and marvel at the many ways we change — and stay the same — as we journey through life.

Lifespan Developmental psychology is a scientific epic story of human growth from infancy to late adulthood. This chapter introduces the foundational concepts and research methods in developmental psychology, including naturalistic observation, case studies, and controlled experiments. We delve into what constitutes “normal” development and tackle pressing issues such as the continuous versus discontinuous nature of development, the interaction of nature and nurture, and the diversity of developmental pathways.

Our discussion extends to the steps, stages, phases, and seasons of lifespan development, providing a structured framework to understand the progression of human growth. We then transition to “Big Picture Models of Lifespan Development,” where we explore the Indigenous Connectedness Framework and Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, offering insights into the relational, social, and environmental and systemic aspects of development.

We will then explore “Focused Perspectives on Lifespan Development,” examining key studies and theories that have shaped our understanding of human development. This includes the famous doll experiment by Mamie and Kenneth Clark, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognition, and Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. We also review Piaget’s stages of cognitive development and delve into moral development through the lens of Kohlberg and Gilligan, alongside discussions on racial identity, feminist identity, and spiritual development.

We finish this chapter by exploring the stages of biological development from prenatal stages to adolescence, and the emerging adulthood phase. We give special attention to the impact of the Indian Residential School System on healthy development, highlighting the importance of understanding the impacts of harm and the vital role of resilience within developmental contexts.

Through this comprehensive overview, our goal is to give you a deep understanding of the nature of human development, encouraging a holistic and inclusive approach to studying the human lifespan.

Research Methods in Developmental Psychology

In a previous chapter we discussed a variety of research methods used by psychologists. Developmental psychologists use many of these approaches in order to better understand how individuals change mentally and physically over time. These methods include naturalistic observations, case studies, surveys, and experiments, among others. Here is a brief refresher of some of these research methods used by developmental psychologists.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observations involve observing behaviour in its natural context. A developmental psychologist might observe how children behave on a playground, at a daycare centre, or in the child’s own home. While this research approach provides detailed information into how children behave in their natural settings, researchers also have very little control over the types and/or frequencies of displayed behaviour. One important, naturalistic study on the impacts of TV on children’s development was conducted in British Columbia by Tannis MacBeth and her colleagues (Heilbronn & Williams, 1987). MacBeth’s internationally famous work has even been made into a full-length graphic novel.

Case Study Methodology

In a case study, developmental psychologists collect a great deal of information from one individual in order to better understand physical and psychological changes over the individual’s lifespan. This particular approach is an excellent way to better understand individuals who are exceptional in some way, but it is especially prone to researcher bias in interpretation, and it is difficult to generalise conclusions to the larger population.

Survey Method

The survey method asks individuals to self-report important information about their thoughts, experiences, and beliefs. This particular method can provide large amounts of information in relatively short amounts of time; however, validity of data collected in this way relies on honest self-reporting, and the data is relatively shallow when compared to the depth of information collected in a case study.

Controlled Experiments

Experiments involve significant control over extraneous (not relevant or related to the subject) variables and manipulation of the independent variable. As such, experimental research allows developmental psychologists to make causal statements about certain variables that are important for the developmental process. Because experimental research must occur in a controlled environment, researchers must be cautious about whether behaviours observed in the laboratory translate to an individual’s natural environment.

What is “Normal” Development?

It is natural for us to ask, “what is normal development?” When we try to answer this question from an evidence-based approach, we discover that what is “normal” for children of a certain age varies by race, gender, culture, economic resource, access to health care, experiences with significant stressors, and so on. Historically, normative psychologists studied large numbers of children from predominantly WEIRD backgrounds (see definition in textbox) at various ages to attempts to establish norms (i.e., average ages) of when most children reach specific developmental milestones in each of the three domains (Gesell, 1933, 1939, 1940; Gesell & Ilg, 1946; Hall, 1904). By being mindful of the errors that can happen when we over-generalise western norms, we can use these age-related averages as imperfect guidelines to compare children with same-age peers to determine the approximate ages at which they may reach specific normative events called developmental milestones (e.g., crawling, walking, writing, dressing, naming colours, speaking in sentences, and starting puberty).

Note: WEIRD stands for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

This term is used to describe the type of backgrounds that a lot of psychological research is based on. Historically, many studies have focused on people from countries or societies that are wealthy, have high levels of education, and democratic governments. The problem is that not everyone in the world lives in these kinds of places or has these experiences.

Issues in Developmental Psychology

In this chapter, we will explore various theoretical perspectives on human development that seek to explain how people change over time. Our discussions will cover key debates, such as the continuous or discontinuous nature of development, the universality or individuality of developmental pathways, and the interplay between genetics and environment. We will also delve into the pros and cons of a broad perspective versus focused details; understand the practical and therapeutic applications of lifespan theories; examine the disproportionate impact of discriminatory, social, environmental, and health factors on minorities’ development; reflect on how challenges can be forces that foster growth; and acknowledge the need for improving research practices in lifespan studies.

Is Development Continuous or Discontinuous?

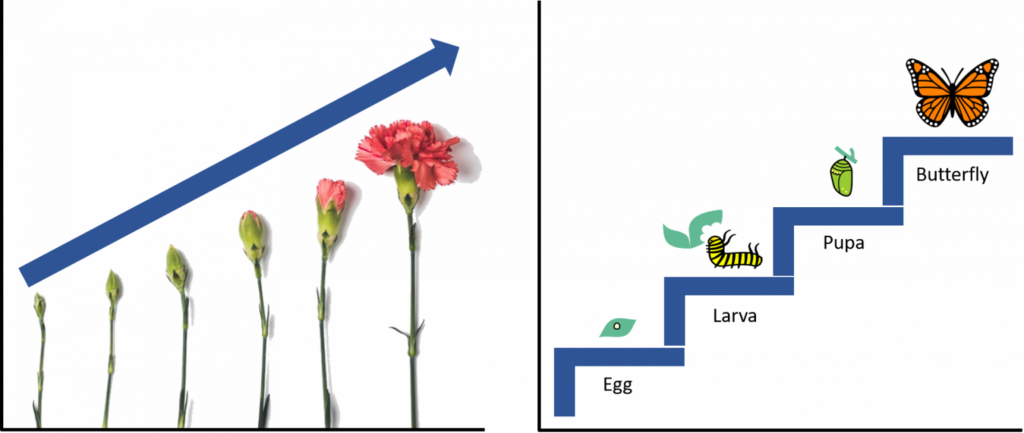

Continuous development is an additive or cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills. For example, as a flower grows, we see millimetres added to its height day by day. Discontinuous development, in contrast, happens in distinct stages and occurs at specific times or ages, such as a butterfly’s growth from egg to larva, pupa, and adult butterfly, respectively (Figure LD.2).

Is There One Course of Development or Many?

Does child development follow a universal pattern, or is it individualized, shaped by each child’s unique genetic makeup and environment? Some stage theorists predict that the course of development is universal, with growth occurring in both predictable continuous sequences and spurts of discontinuous growth. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children, regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to alter the timing of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 2010).

For example, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down, in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later, at around 23 to 25 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk at around 12 months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age 9, their motor skills surpass those of American children of the same age; 9-year-old Aché children are able to climb trees up to 25 feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan & Dove, 1987). So, development can be influenced by different contexts, but the functions themselves are present in all societies (Figure LD.3).

How Do Nature and Nurture Influence Development?

To what extent do nature (biology and genetics) and nurture (environment and culture) contribute to development? We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye colour, height, and certain personality traits. There are also important interactions between our genes and our environment; our unique experiences in our environment influence if and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). In the early years of psychology it was popular to debate Nature or Nurture. In contrast, this chapter will show that there is a reciprocal, back and forth interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

The Hard Choice Between Big Picture versus Focused Details

It is not possible to see all the ways in which we humans change, in every circumstance, in every social and environmental setting, and during every year of our lives, all at once. If we are to understand the patterns of human growth, we necessarily need to focus on one observable piece of the mystery — one part of the story of human change at a time. We need to create a model.

A model is a simplified, often visualized narrative or story that helps guide our observations and analyses as we actively seek out behaviours. A model could be a big-picture overview of human development in a holistic web of environmental, community, intergenerational, family, cultural, and spiritual interconnections — for example, Indigenous Interconnectedness Framework. A model could also be the highly interactive interdependent relations and dynamics at play with the human systems that surround an individual as they grow (e.g., Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory).

In addition, a model can also be focused on the fine details of one human capacity (e.g., Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, and Fowler’s stages of spiritual development).

There is tension when we adopt any model, however. On the one hand, in a big-picture overview we may not see the intricacies afforded by focusing on the fine details. On the other hand, when we focus on a single human capacity or other more precise details, we may miss understanding how the big picture influences our interpretations. This tension is both a blessing and a challenge when we have to use models and create narratives about human development.

Social and Environmental and Health Factors Impact Minorities Harder

Developmental delays, significantly impeding (slowing down or stopping) healthy growth, can be caused by factors such as poverty, neglect, and racism, each introducing unique challenges that gradually undermine development and wellness. Poverty restricts access to essential resources, limiting opportunities for growth and negatively affecting academic achievement (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014; Kim & Rouse, 2011). Neglect, characterised by a lack of physical and emotional support from caregivers, leaves lasting scars that negatively affect emotional well-being and contribute to psychological disorders and cognitive impairments (Norman et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2009). Racism not only hinders educational advancement and increases academic disparities (gaps) but also adversely affects mental and physical health, with the chronic stress from racial discrimination leading to biological wear and tear, known as allostatic load, thereby fostering long-term health disparities (Gershenson et al., 2016; Trent et al., 2019).

Counter-Intuitively, Challenges Can Stimulate More Growth than Calm

Growth and learning fundamentally come from our responses to challenge, conflict, or provocation. While it might seem intuitive to associate growth and learning with comfort and stability, many psychological and philosophical theories actually underscore the crucial role of conflict, challenge, and provocation in stimulating these processes (Dweck, 2006; Nietzsche, 1888; Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). If we are always comfortable and all our needs were always met, there would be no reason for us to grow or learn. Lifespan developmental scientists and therapists celebrate and dig deeper into our moments of challenge. For example, our sudden surprise while encountering something new, our experience of threat and fear, our wish for something more, our pain after a great loss, and our accommodating to our changing biology can all provoke our growth and learning. When philosopher Nietzsche said, “what does not kill me, makes me stronger,” (Nietzsche, 1886/1998) he was summing up one of the paradoxes in our discipline — that positive change requires challenge and conflict as much, or more, than comfort and stability. Of course, to thrive as happy, healthy humans, we need to find a balance between challenge/conflict and comfort/stability (Ryff, 1989; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

As we work through this chapter, it is important to start on common ground by understanding some basic terminology used within our field. Let’s begin by defining the terms ‘steps’/sequences,’ ‘stages’, ‘phases’, and ‘seasons’ of lifespan development, which we will be using frequently throughout this chapter.

Steps, Stages, Phases, and Seasons of Lifespan Development

Outside of lifespan development, terms such as “steps/sequences,” “stages,” “phases,” and “seasons” might be used interchangeably, but within the context of lifespan developmental science, these terms have significant differences in meaning.

Steps or Sequences

Steps or sequences (i.e., adding skill upon skill) often refer to specific, measurable tasks or actions within a larger process, that usually, but not always, need to be performed in a sequential order. For instance, in the realm of child development, the ability to walk is a crucial step that usually comes after crawling (Berger, 2014).

Stages

Stages (transformations) imply a broader view of development. They are typically associated with theory-based models of lifespan development such as stages of psychosocial (Erikson, 1950), cognitive (Piaget, 1952) and moral development (Kohlberg, 1981). Each stage represents a unique set of developmental tasks or conflicts that must be resolved before an individual can move to the next stage. Because there is a qualitative transformation, by definition, it is theoretically impossible to return to a prior stage (except in the case of brain injury). For example, once you are born, there is no going back into the womb.

Phases

Phases, in the context of development, are less strictly defined than steps/sequences and stages. Phases can be thought of as broader periods or epochs in an individual’s life where certain characteristics, behaviours, or experiences are more prevalent (Neugarten, 1979).

Seasons

Seasons (recurring rhythms of change) in lifespan development represent cyclical, recurrent, or natural periods that capture the fluid and rhythmic progression of life. For example, our human life span can be described as the physical seasons of nature: Spring (birth), Summer (youth), Autumn (middle age), and Winter (elder years). This perspective underscores the continuous cycle of growth and transformation throughout the lifespan (Levinson, 1986; Hodge, Struthers, & Geishirt Cantrell, 2002).

These terms provide a framework for understanding both the continuous, discontinuous, and recurring patterns of human development, yet it is crucial to recognise that individual experiences can vary significantly and might not always adhere to these structured concepts (Lerner, 2006).

Conclusion

In concluding this section on developmental psychology’s basics, we recognise that studying human development is both complex and intriguing. We have covered various research methods, the nature versus nurture debate, developmental stages, and the influence of societal and environmental factors. This examination reveals the diversity and complexity of human growth, enhancing our understanding of both ourselves and others. Moving forward, it’s important to remember that developmental study goes beyond merely noting changes; it involves understanding the many experiences that shape and define us as we grow. With this knowledge, we can better understand patterns of growth, address life’s challenges and achievements, and appreciate our interdependent connection to the broader world.

Next

Moving from research methods in developmental psychology, we now focus on “Big Picture Models of Lifespan Development.” This section examines human development through cultural lenses and theoretical frameworks. We start with the Indigenous Connectedness Framework, which sheds light on a child’s relational identity and the role of culture and environment in development. We also review Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, placing individual development within a network of relationships influenced by various environmental levels. These are just two of several other Big Picture Models that facilitate our search for the many individual, social, and environmental influences that affect human development.

Image Attributions

Figure LD.1. National Spelling Bee Winners by Jessica Motherwell-McFarlane is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure LD.2. Cyanocorax adapted by Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license.

Figure LD.3. (a) Image by Michelle Raponi from Pixabay and (b) Image by Tania Dimas from Pixabay are used under the Pixabay Content License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).