Chapter 16. Gender and Sexuality

Introduction to Gender

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 49 minutes

In this section, we will explore gender, unravelling the distinctions between sex, gender, and sexual orientation. When was the last time you encountered a questionnaire asking for your gender? Did it make you think about the deeper meaning behind these categories? Our goal is to shed light on these concepts, often clouded by misconceptions and societal norms.

We will learn about the limitations of the traditional binary system of gender identification. We’ll explore the various genders including non-binary and genderqueer. We will also consider Two-Spirit and other gender perspectives in Indigenous cultures.

This section also discusses gender dysphoria and its impact on mental health. We’ll look at how gender identity develops from childhood through adulthood, guided by both social and biological influences. This section is more than a collection of terms and theories; it’s an invitation for you to understand and embrace the wide diversity of human gender experiences.

What Do We Mean by “Gender” and “Sex”?

In popular media and everyday conversations, the terms gender and sex are often used as if they mean the same thing. However, in academic research and data collection, these terms have distinct and important meanings. Understanding these differences is crucial for a clear and accurate discussion about identity and biology.

Sex

Sex refers to the biological attributes of a person. This includes a range of physical and physiological features such as chromosomes, hormone levels, internal and external reproductive organs, and secondary sex characteristics. Generally, sex is categorised as female, intersex, or male and these categorisations are usually made at birth, based on visible anatomy.

Gender

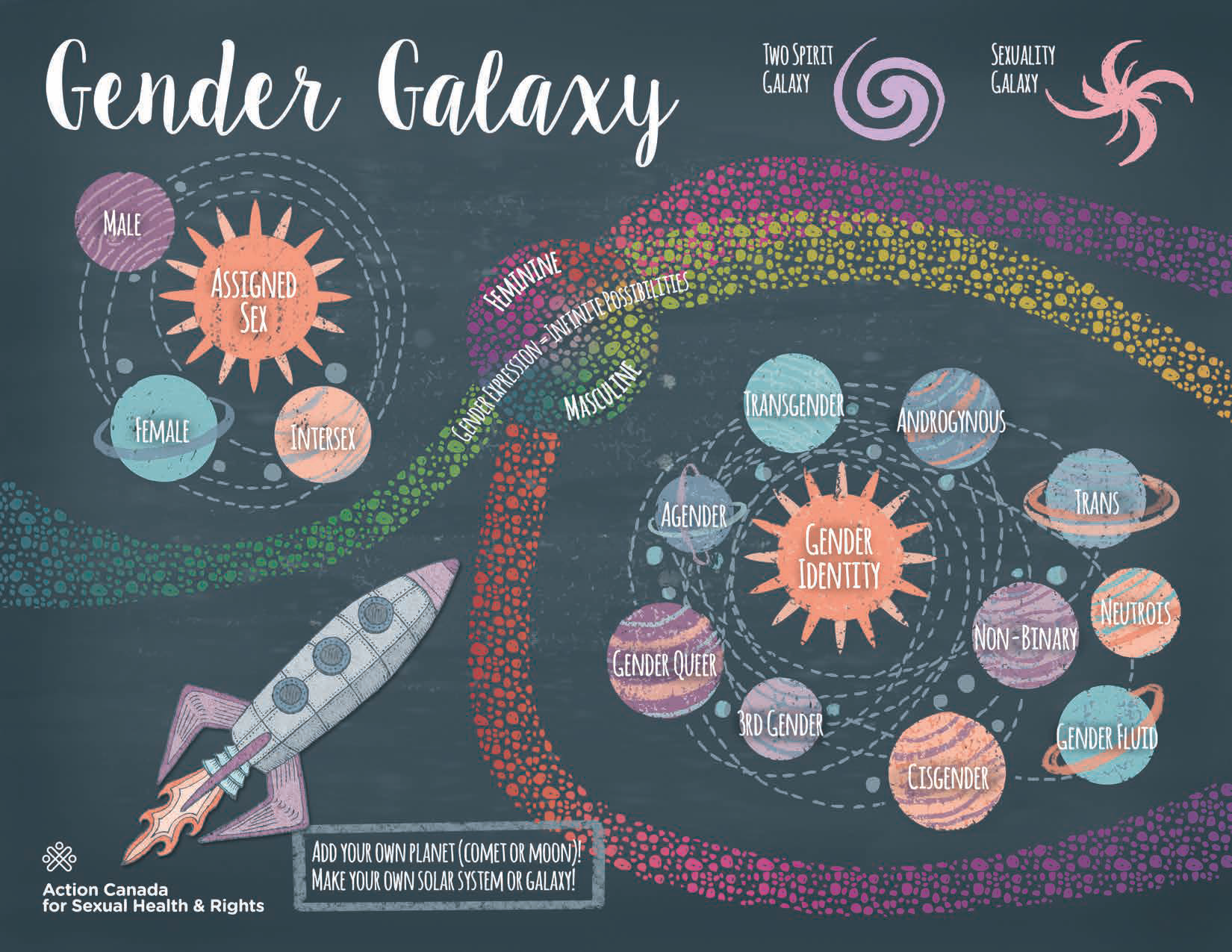

Gender is a socially constructed concept. It relates to the roles, behaviours, activities, and attributes that a given culture considers appropriate for men and women. Gender is more about how society labels and categorises individuals rather than their biological characteristics. It encompasses a range of identities, including man, woman, a blend of both, neither, or anywhere in the ‘gender galaxy’ – a term we discuss below.

Gender galaxy

Gender Galaxy is a model that helps us understand the variety of gender identities and expressions. Just as a galaxy contains many different stars and objects connected by gravity, gender includes many identities linked by personal experiences and societal influences. Like space objects that can look alike but be different, or look different but be similar, people’s gender identities can be diverse regardless of appearance. Like space there is room for vast definitions and formations of gender — no need to limit the experience of gender by using restrictive binaries or categories. Some genders stay the same or change predictably, while others shift in more complex ways, similar to how celestial bodies move and change in space. For more refer to Trans Language Primer

The concept of gender involves three interrelated aspects: body, identity, and social role.

- Gendered body refers to the physical experience of being female, intersex, or male. This includes how individuals perceive their own bodies and how society assigns gender based on physical attributes.

- Gender identity is our internal understanding and personal experience of our own gender. This may or may not align with the sex assigned at birth. For example, someone assigned to the female gender at birth may identify as a man, or someone assigned to the male gender at birth may identify as non-binary.

- Gender role expression involves how we present our gender to the world through our behaviour, clothing, and interactions.This expression can vary greatly and may or may not conform to societal expectations of gender roles.

Watch this video: What is Gender-Inclusive Language? (1 minute)

“What is Gender-Inclusive Language?” video by University of Nebraska System is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

It’s important to recognise that gender identity is a deeply personal aspect of who we are. It’s about how we understand ourselves and navigate our place in the world. Our understanding of our own gender can evolve over time and is influenced by a complex mix of societal, cultural, and personal factors.

Gender expansiveness

What is gender expansiveness? Imagine a world where there are no social or financial privileges or punishments attached to your gender identification. Imagine you and everyone else are guaranteed equitable access to food, shelter, education, and jobs. Imagine that you did not have to be in a special gender group to receive special privileges. Perhaps in this world, at the moment of your birth the answer to, “Is it a boy or a girl?” doesn’t decide who will be first to inherit your family’s assets. Imagine that babies born with a penis and scrotum are no more or less treasured than babies born with a clitoris and vulva or babies born with intersex-appearing genitals. In this world your gender is yours to define, develop, design and redesign. Your gender is an essential part of you that becomes part of how you experience your physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual being.

This world gives us an example of what gender expansiveness looks like. Gender expansiveness is a diverse, fluid, creative, changeable identity. Gender expansiveness might have something to do with femaleness, intersexness, or maleness, or all of the above. It also can include people who feel gender is an irrelevant (not applicable) identification for them. Gender expansive (that is, gender beyond a strict female/male binary system) ideas are not new. There are modern cultures and societies, such as some Indigenous communities where gender expansiveness is actively practiced.

Gender expansiveness is being applied in real-world policies. A prime example of this application can be seen in Canada’s progressive steps towards gender inclusivity, particularly in the realm of official documentation.

Gender Identities

Genderqueer

Genderqueer describes a gender identity that doesn’t fit within the traditional categories of “female” or “male,” encompassing experiences that may be a mix of both, neither, or something entirely different. Genderqueer individuals may use a variety of pronouns, such as they/them, she/her, he/him, or others, depending on what feels most affirming to them.

Gender Binary and Its Impact

In many societies, the gender binary system, with its strict female/male dichotomy, historically grants power and resources predominantly to males, often marginalising those who do not conform. This binary perspective not only shapes societal structures but also poses significant challenges for non-binary and genderqueer individuals. In societies adhering rigidly to this binary system, these individuals frequently face barriers in accessing resources, employment opportunities, and social acceptance.

However, there have been many exceptions to this strict gender binary system in the past. Matriarchal (women-dominated) cultures, Indigenous, and other collectivistic societies are structured so that all food and wealth are shared equitably among the members of the community. A value system in which males receive resources first would be a bizarre concept to members of a collectivistic society.

The limitations imposed by a binary misunderstanding of gender highlight the need for a more inclusive approach that recognises and respects the all-gender identities.

Indigenous Perspectives on Gender Diversity and the Two-Spirit Identity

Many Indigenous societies historically recognise more than two genders, offering a more inclusive and fluid view of gender beyond the binary model. In these cultures, gender is often seen as dynamic, allowing individuals to move between roles and be valued for their unique contributions. This broad understanding of gender diversity is exemplified in the concept of “Two-Spirit”, a term used by some Indigenous communities in Turtle Island/North America to describe folks whose identities blend female-ness/femininity and male-ness/masculinity). (Note: see below for a discussion of some of the problems with the term Two-Spirit.) Two-Spirit individuals often hold esteemed positions, navigating between traditional gender roles and carrying spiritual significance. Historically, before colonisation, Indigenous societies, including women, intersex individuals, and men, enjoyed equitable social status and thrived on a system of reciprocity and shared resources, challenging conventional notions of property and gender segregation. The Two-Spirit identity, therefore, is not just a label for a non-binary experience but a reflection of the rich, complex Indigenous understandings of gender.

Two-spirit: Indigenous non-binary genders

“A few things Two-Spirit people from all Native Nations have in common are that we can embody, literally, masculinity and femininity roles with strength: we can play with our genders, sexes, and sexualities to point out how serious all of us can be; we’re sexy, hot, and fierce; and unfortunately, we have had our experiences appropriated, misunderstood, categorised, diagnosed, institutionalized, neglected and hated simply because we exist. The things that bind us are not separate from each other. Of course we have always been fabulous, but we’ve become ultra-fierce since having to deal with being hated by our families and living in cities with our new families.”

(Cruz, 2011. p. 54)

In 1990, Indigenous communities adopted the term “Two-Spirit” to reclaim and revitalize Indigenous gender systems that had been severely disrupted and nearly erased due to the colonization, violent occupation, and cultural genocide perpetrated by European colonists. The purposes of adopting the term Two-Spirit were, first, to discard the derogatory term “berdache” and, second, to restore respect, recognition, and understanding to the wide diversity of Indigenous gender identities (Vowel, 2016). There are advantages and disadvantages to the term Two-Spirit, which originated from the Anishinaabemowin language, where “neizh” means “two” and “manitoog” means “spirit” (Medicine, 2002; Vowel, 2016; Robinson, 2020). The term “Two-Spirit,” however, is an imperfect, incomplete, modern term that is designed to help European settlers, who likely see the world through female/male binary gender lenses, better understand that traditional gender identities are very different from 2SLGBTQIA+ identities. The term “Two-Spirit” is widely recognised and helps reconnect Indigenous individuals with their cultural roles, but it also risks oversimplifying complex identities and may be misunderstood as reinforcing a binary view of gender.

The term “berdache”

The term “berdache”, historically used by European anthropologists for Indigenous non-conforming gender identities, is now considered offensive and inaccurate.

In conclusion, the term “Two-Spirit” serves as a bridge, allowing for an initial understanding and appreciation of non-binary genders within Indigenous cultures, while also highlighting the need for respect and recognition of these diverse identities. This acknowledgment paves the way for creating more specific language to describe non-binary Indigenous gender identities. “Indigiqueer” is one term introduced as an alternative to Two-Spirit.

Indigiqueer

“Indigiqueer”, introduced as an alternative to “Two-Spirit”, is a term that resonates more with their identity, reflecting the evolving nature of gender and sexual identities in Indigenous cultures.

The term “Indigiqueer” is most credited to Dr. Qwo-Li Driskill, a Two-Spirit, queer, and mixed-race Cherokee poet, scholar, and activist. Driskill’s work in Indigenous and Two-Spirit studies has significantly contributed to the visibility and understanding of Indigenous queer identities. (Driskill et al., 2011).

Adding the “2S” for inclusion

In this textbook, we will use the acronym 2SLGBTQIA+ to represent a diverse range of sexual and gender identities. The inclusion of “2S” at the beginning of the acronym specifically highlights “Two-Spirit”as a distinct identity, separate from LGBTQIA+ categories. This distinction is crucial, as “Two-Spirit” is a term unique to Indigenous cultures, encompassing a range of traditional gender identities and roles that do not necessarily align with Modern LGBTQIA+ concepts. By placing “2S” first, we acknowledge and respect the unique cultural, spiritual and historical significance of Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer identities within Indigenous communities, while also embracing the broader spectrum of sexual and gender diversity represented in the LGBTQIA+ community.

In conclusion, “Two-Spirit” is an important term in Indigenous cultures, providing a perspective on gender that goes beyond the usual binary categories. Although it doesn’t fully capture the complexity of traditional Indigenous gender roles, its use has paved the way for other terms like “Indigiqueer”. These newer terms continue to evolve, highlighting the diverse and changing nature of gender and sexual identities in Indigenous communities and emphasising the need to respect these varied identities.

Watch this video: What Does “Two-Spirit” Mean? | InQueery | them. (6 minutes)

“What Does “Two-Spirit” Mean? | InQueery | them.” video by them is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Canada’s Gender-Inclusive Passport Policy

As of August 2017, Canada introduced an “X” gender designation on passports for individuals who do not wish to specify their gender as female or male. This move was part of broader efforts to recognise and accommodate non-binary, intersex, and transgender Canadians (Government of Canada, 2017).

Genders Defined

Cisgender

When we talk about gender, it’s important to understand the term ”cisgender”. Cisgender refers to individuals whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth. In simpler terms, if you were born with female anatomy and identify as a woman, or were born with male anatomy and identify as a man, you’re cisgender.

What does “cis” and “trans” mean?

“Cis” means “same” in Latin. In the context of the term “cisgender”, it is used to denote that a person’s gender identity corresponds to or is the same as their sex assigned at birth. This is in contrast to “trans”, used in “transgender”, which comes from Latin and means “across”, “beyond” or “on the opposite side”. These prefixes help one to understand the relationship between one’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth, in both cisgender and transgender individuals.

Some people have a gender identity that aligns with their birth-assigned sex, others might have a gender identity that differs from it.

Transgender

Transgender — or trans — refers to individuals whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. Simply put, if someone was born with female anatomy but identifies as a man, or was born with male anatomy but identifies as a woman, they are transgender. In addition, transgender identities aren’t necessarily bound by this reversal of binaries. Trans can be an umbrella term that encompasses non-binary, agender, and gender fluid people, too.

Gender Non-binary

Non-binary is a term that is often used to describe a gender identity that doesn’t fit within the traditional binary of female or male. People who identify as non-binary may see themselves as a blend of both genders, as neither, or may even experience a fluid gender identity (Richards et al., 2016). Example: A person may not feel strictly male or female, but a mix of the two. They don’t necessarily align with ‘woman’ or ‘man’ but somewhere in between or completely outside these categories, and so they identify as non-binary.

Gender Fluid

Gender fluid refers to a gender identity which varies over time. A gender fluid person may at any time identify as female, male, neutrois, or any other non-binary identity, or some combination of identities (Richards et al., 2016). Example: Someone might feel more ‘female’ some days and more ‘male’ on others, or they may feel that their gender identity changes over time rather than being constant, identifying as gender fluid.

Neutrois

Neutrois is a term used to describe a non-binary gender identity characterised by a lack of connection to or alignment with the traditional binary concepts of female or male. Neutrois individuals may experience a sense of neutrality, absence of gender, or a gender that is neither female nor male. In other words, they perceive their gender as irrelevant to their identity or personality (Westbrook & Saperstein, 2015). Example: A person might feel that their interests, behaviours, and personal characteristics aren’t related to the concept of gender at all, thus identifying as gender irrelevant or neutrois.

Gender Non-conforming

Gender non-conforming refers to individuals whose gender expression or identity deviates from societal expectations associated with their assigned sex at birth. It encompasses diverse presentations and may or may not be associated with identifying as transgender.

Self-reflection Activity

Now that you have read the definitions of gender, take a moment to complete Table GS.2 and record how you currently identify. Remember your answers today may change over time or stay the same.

| I identify as… | Not at all | A little | Somewhat/Sometimes | Often | Very much |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Woman | |||||

| A Man | |||||

| Gender Fluid | |||||

| Intersex | |||||

| Gender Non-Binary | |||||

| Neutrois | |||||

| Transgender | |||||

| Cisgender | |||||

| Gender Non-Conforming |

As our psychological science gets more gender-expansive we will be able to add more rows to Table GS.2. Gender Identification: Several sliding scales model to reflect new categories of gender identifications. For more expansive gender identification information, study the Gender Galaxy (Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights: Gender and Sexuality Galaxies – Comprehensive Sexual Health Education Tool.

Watch this video: 10 Gender Identities Beyond Male And Female (4.5 minutes)

“10 Gender Identities Beyond Male And Female” video by TheThings Celebrity is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Gender Dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is a condition where a person feels discomfort or distress because their gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth (Dhejne, 2017; Faheem, Balasubramanian, & Menon, 2022). It’s important to note that not all transgender or non-binary people experience gender dysphoria, and it can also occur in some cisgender individuals (Cooper, Russell, Mandy, & Butler, 2020).

Gender dysphoria is recognised as a mental health diagnosis and is often a prerequisite for receiving hormone therapy and other gender-affirming treatments (Bhinder & Upadhyaya, 2021; Claahsen – van der Grinten, Verhaak, Steensma, Middelberg, Roeffen, & Klink, 2020). Gender dysphoria can lead to serious mental health issues like anxiety, depression, and thoughts of suicide, making professional support crucial (Mohideen, et. al., 2022).

Treatment for gender dysphoria can significantly improve a person’s psychological well-being and quality of life (Schmidt & Levine, 2015; Ristori, Fisher, Castellini, & Maggi, 2018). However, it’s a complex issue influenced by societal factors like misgendering (when someone refers to a person’s gender inappropriately or uses pronouns for that person that are incorrect for their gender) and transphobia, or prejudice against transgender people (Cooper et al., 2020).

In summary, gender dysphoria is a significant condition that affects many individuals. It requires a thoughtful approach to diagnosis and treatment, focusing on improving the lives and mental health of those affected.

Watch this video: Gender dysphoria: definition, diagnosis, treatment and challenges (5.5 minutes)

“Gender dysphoria: definition, diagnosis, treatment and challenges” video by Demystifying Medicine McMaster is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Development of Gender Identity

Gender Socialisation: Evidence

Early theories of gender development recognised the importance of environmental or familial influence. However, each theory has a slightly different perspective on how that may occur. We will discuss a few of those briefly, but will focus more on major concepts and generally accepted processes.

What is the earliest memory you have of labelling or understanding your own gender (e.g., as a girl, boy, non-binary person, etc.)? Does that label still fit today? Why has it changed or stayed the same? Reflecting on your personal experience can provide insight into how deeply ingrained and complex gender identity development is. It highlights the interaction of individual perception, societal norms, and cultural influences in shaping our understanding of gender from an early age.

The idea that the development of gender identity is the same worldwide, across different countries and cultures (for example, comparing Traditional to Modern cultures) has faced criticism. While some acknowledge that biology can play a role in shaping gender identity, they emphasise the ideas that environmental and social influences are significantly more impactful. This perspective is consistent across various areas of development, including the formation of gender identity. It revisits the classic “nature versus nurture” debate, concluding that both genetic and environmental factors are involved. To overlook either aspect is to misunderstand how development works (Magnusson and Marecek, 2012). In this section, we will delve into the social, environmental, and cultural factors that contribute to the development of gender identity.

Early life

Infants do not prefer gendered toys initially, but by age 2, they begin to show preferences for such toys (Bussey, 2014; Servin, Bhlin, & Berlin, 1999). By age 2, children correctly use words like “girl” and “boy” and can accurately point to a female or male when hearing a gender label. This indicates that children first learn to label others’ gender, then their own, and eventually understand that there are shared qualities and behaviour for each gender (Bussey, 2014; Leinbach & Fagot, 1986).

By a child’s second year of life, they begin to display knowledge of gender stereotypes, a finding observed even in preverbal children (Fagot, 1974). After being shown a gendered item, such as a doll or a truck, they will stare longer at a photograph of the “matching gender” (Serbin, Poulin-Dubois, Colburne, Sen, & Eichstedt, 2001). Children’s approach to gender stereotypes and play changes over time. Initially, their interpretations and adherence to these stereotypes are very rigid. As they reach middle childhood, their approach becomes more flexible, but they often become rigid again in adolescence. Generally, girls are more flexible and boys are more rigid with gender stereotypes (Blakemore et al., 2009; Bussey, 2014). Boys may be more rigid with gender stereotypes as a result of boys experiencing more negative consequences for their gender-non-conforming behaviours.

Gender socialisation is the process in which children learn about gender roles and expectations from their surroundings. Parents often start this process even before a child is born, through choices like specific colours for the nursery or toys deemed appropriate for the child’s gender. As children grow, they pick up cues from their peers about the behaviours that are considered appropriate for girls or boys. TV shows, movies and video games often contribute to gender socialisation by showing female and male characters in stereotypical roles. In schools, teachers may unknowingly encourage these stereotypes through different expectations and interactions with girls and boys. We will next explore how all these factors in combination influence the ways in which children perceive gender and their role in society.

Parents

Parents begin to socialise children to gender long before children can label their own gender. Think about the first moment someone says they are pregnant. One of the first questions is “How far along are you?” and then “Are you going to find out the sex of the baby?” We begin to socialise children to gender before they are even born! We pick out girl and boy names, we choose particular colours for nurseries, types of clothing, and decor, all based on a child’s gender, often before they are ever born (Bussey, 2014).

Infants are born into a gendered world. As they grow, they are often not given the opportunity to develop their own preferences for toys, clothes, and activities, which may or may not align with the gendered categories preferred by their parents. Instead, it is the parents and caregivers who immediately shape these preferences for them (Boe & Woods, 2018; Mesman & Groeneveld, 2018). Parents even respond to a child differently, based on their gender.

For example, in a study in which adults observed an infant that was crying, adults described the infant to be afraid when they were told the infant was a girl. However, they described the baby as angry or irritable when told the infant was a boy (Parsons et al., 2017). Moreover, parents often reinforce dependence in girls and independence in boys. They also overestimate their sons’ abilities and underestimate their daughters’ abilities (Endendijk et al., 2017). Research has also revealed that prosocial behaviours are encouraged more in girls than boys (Chu et al., 2022).

On average, boys are more gender-typed and fathers place more focus on this (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). As children develop, parents also tend to continue gender-norm expectations. For example, boys are encouraged to play outside (cars, sports, balls) and build (Legos, blocks), etc., and girls are encouraged to play in ways that develop housekeeping skills (dolls, kitchen sets) (Bussey, 2014). What parents talk to their children about is different, based on gender, as well. For example, they may talk to daughters more about emotions and have more empathic conversations, whereas they may have more knowledge and science-based conversations with boys (Bussey, 2014).

Parental expectations can have significant impacts on a child’s own beliefs and outcomes including psychological adjustment, educational achievement, and financial success (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). When parents adopt more gender-equal or neutral interactions, research shows positive outcomes (Bussey, 2014). For example, girls tend to do better academically when their parents adopt a gender-equal or neutral approach. This approach contrasts with gender-traditional families.

Peers

Peers have a strong influence on gender and how children play, which increases as children get older. In early childhood, peers are pretty direct about guiding gender-typical behaviours. As children get older, their corrective feedback becomes subtler. So how do peers socialise gender? Non-conforming gender behaviour (e.g., girls playing with trucks, boys playing with dolls) is often ridiculed by peers, and children may even be actively excluded for this behaviour. This situation influences the child to conform more closely to gender-traditional expectations (e.g., girl stops playing with a truck and picks up the doll).

Children tend to play in sex-segregated peer groups. We notice that girls prefer to play in pairs while boys prefer larger group play. Boys also tend to use more threats and physical force whereas girls do not prefer this type of play. Thus, there are natural reasons to not play in mixed-gender groups and to instead tend towards segregation (Bussey, 2014). The more a child plays with same-gender peers, the more their behaviour becomes gender-stereotyped. By age 3, peers will reinforce one another for engaging in what is considered to be gender-typed or gender-expected play. Likewise, they will criticise, and perhaps even reject, a peer who engages in play that is inconsistent with gender expectations.

Media and advertising

Media includes movies, television, cartoons, commercials, the internet, video games, and print media (e.g., newspapers, magazines). In general, the media tends to portray women as dependent and emotional, low in status, in the home rather than employed, and their appearance is often a focus, whereas males are portrayed as more direct, assertive, muscular, in authority roles, and employed. We have seen a slight shift in this in many media forms, although it is still very prevalent, that began to occur in the mid- to late 1980s and 1990s (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017). Television’s impact on children is significant. The more they watch TV, the more they develop gender stereotypical beliefs (Durkin & Nugent, 1998; Kimball 1986). Even video games have gender-stereotyped focuses. Females in video games tend to be sexualised and males are portrayed as aggressive (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017).

School influences

Research tends to indicate that teachers place a heavier focus, in general, on males — this means that they not only get more praise, they also receive more correction and criticism (Simpson & Erickson, 1983). Teachers also tend to praise girls and boys for different behaviours. For example, girls are acknowledged for more domestic qualities such as having a tidy work area, whereas boys are praised more for their educational successes (e.g., grades, skill acquisition) (Eccles, 1987). Overall, teachers place less emphasis on girls’ academic accomplishments and focus more on their cooperation, cleanliness, obedience, and quiet/passive play. Boys, however, are encouraged to be more active, and there is certainly more of a focus on academic achievements (Torino, 2017).

For example, in adolescence, girls tend to be more focused on relationships, whereas boys are more career-focused (again, this aligns with the emphasis that educators place on children, based on their gender). Girls may also be oriented toward relationships and their appearance rather than careers and academic goals if they are very closely identifying with traditional gender roles. They are more likely to avoid science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)-focused classes, whereas boys seek out STEM classes more frequently than girls do. This can impact major choices for girls who go to university, since they may not have experiences in STEM to foster STEM-related majors (Torino, 2017). As such, the focus educators place on children can have lasting impacts. Although we are focusing on the negative, think about what could happen if we saw a shift in that focus!

Having examined the evidence for gender socialisation, in Supplement GS.11 we discuss theories and explain how and why we learn and adopt gender roles and identities. First, we discuss Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, which suggests that we learn gender behaviours by watching and copying others (Ata, 2018; Onay & Kıylıoğlu, 2021; Grusec, 2020). Next, we look at the ways in which social cognitive theory builds on this idea by highlighting how feedback and direct teaching shape our understanding of gender norms. We also examine cognitive theories, like Lawrence Kohlberg’s Cognitive Developmental theory, which proposes that children actively search for information about gender, and the Gender Schema theory, which explains how children develop mental scripts or shortcuts for understanding gender. Finally, we’ll look at the genetic theory of gender identity formation, which provides a different angle on the psychological perspectives.

Moving from theoretical discussions to a real-world example, Supplement GS.12 discusses the case of David Reimer and provides a crucial perspective on gender socialisation and research ethics. While theories like Social Learning theory and Gender Schema theory offer insights into how we learn gender roles, Reimer’s story highlights the complex interaction between upbringing and biology in shaping gender identity. His experience in which a medical accident led to him being raised as a girl before he chose to live as a male challenges the notion that gender identity is solely determined by socialisation. This case shows that not only is gender identity influenced by both our environment and our biology, but also that Dr. Money could be so convinced of his theory that he was willing to commit crimes against David in search of evidence to support Money’s theory.

Summary: Introduction to Gender

This section provides a comprehensive overview of gender, starting with the basic concepts of “gender” and “sex” and expanding into gender inclusivity and diversity. It introduces the ideas of gender expansiveness, and a gender galaxy challenging traditional views and encouraging a broader understanding of gender beyond the binary classification.

The section on gender identities dives into the impact of the gender binary system and highlights indigenous perspectives on gender diversity, including the Two-Spirit identity and Indigiqueer concepts. It explores various gender identities such as cisgender, transgender, gender non-binary, gender fluid, and more, through definitions and examples. Gender dysphoria is explained with an explanation of its definition, diagnosis, treatment, and challenges

The development of gender identity is explored through the lens of gender socialisation, presenting evidence from early life, parental influence, peers, media, and school.

Image Descriptions

Figure GS.3. Gender Galaxy image description: Two suns with planets revolving around them and an asteroid belt separating them. The first sun is labelled “Assigned Sex” and three planets revolve around it, labelled “Male”, “Female”, and “Intersex”. The second sun is labelled “Gender Identity” and ten planets revolve around it, labelled “Transgender”, “Androgynous”, “Trans”, “Neutrois”, “Non-Binary”, “Genderfluid”, “Cisgender”, “3rd Gender”, “Genderqueer”, and “Agender”. The asteroid belt has the words “Feminine”, “Masculine”, and “Gender Expression = Infinite Possibilities”. In the foreground, there is a rocket ship with the text “Add your own planet (comet or moon)! Make your own solar system or galaxy!”. In the distance, there is the “Two Spirit Galaxy” and the “Sexuality Galaxy”. [Return to Figure GS.3]

Image Attributions

Figure GS.3. Gender Galaxy is used with permission from the copyright holder. Permission is granted for reuse in future iterations of Introduction to Psychology: Moving Towards Diversity and Inclusion.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).