Chapter 7. Memory

Long-Term Memory: Categories and Structure

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 19 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe and contrast explicit and implicit memory

- Describe how long-term memory may be categorised, structured, and investigated

- Respect the value of semantic knowledge and autobiographical memory

- Acknowledge the functions of visual encoding and spatial memory in the daily life

Categories of Long-Term Memories

Although it is useful to hold information in sensory and short-term memory, we often rely on our long-term memory (LTM). Long-term memories fall into two broad categories:

Explicit Memory

Explicit memory — also referred to as declarative memory — refers to knowledge or experiences that can be consciously remembered. There are two types of explicit memory: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory refers to the firsthand experiences that we have had (e.g., recollections of our high school graduation day or of the fantastic dinner we had in Vancouver last year). Semantic memory refers to our knowledge of facts and concepts about the world (e.g., that the capital city of Canada is Ottawa and that one definition of the word “affect” is “the experience of feeling or emotion”). Explicit memory is assessed using measures in which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the information. A recall test is a measure of explicit memory that involves bringing from memory information that has previously been remembered. We rely on our recall memory when we take an essay exam, because this test requires us to generate previously remembered information. A multiple-choice test is an example of a recognition test, a measure of explicit memory that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before.

Implicit Memory

Implicit memory — also referred to as non-declarative memory — refers to things we can remember without awareness of having learned them. Implicit memory is important because it can affect our behaviour without us being aware of how. Procedural memory refers to our often knowledge of how to do things. Procedural memory can be implicit, because we are not required to consciously process the procedural steps for engaging in the activity (e.g., brushing your teeth or riding a bike). A second type of implicit memory involves classical conditioning. Our brains are amazing at connecting things without us even realising it. Imagine smelling something and suddenly thinking of a tasty food you love. That’s our brain making a link between the smell and the food. It happens without us trying, and it can make us feel happy or make our mouths water. Our brain loves to create these connections, even if we’re not paying attention to them.

Implicit memory can also be shown by studies on priming, or changes in behaviour as a result of experiences that have happened frequently or recently. Priming refers both to the activation of association (e.g., we can prime the concept of kindness by presenting people with words related to kindness) and to the influence of that activation on behaviour (e.g., people who are primed with the concept of kindness may act more kindly). The key point about implicit priming is that memories we are not consciously aware of can still affect our feelings and behaviour.

One measure of the influence of priming on implicit memory is the word fragment test, in which a person is asked to fill in missing letters to make words. You can try this yourself. First, try to complete the following word fragments, but work on each one for only three or four seconds. Do any words pop into mind quickly?

_ i b _ a _ y

_ h _ s _ _ i _ n

_ o _ k

_ h _ i s _

Now, read the following sentence carefully:

You might find that it is easier to complete fragments 1 and 3 as “library” and “book,” respectively, after you read the sentence than it was before you read it. However, reading the sentence did not really help you to complete fragments 2 and 4 as “physician” and “chaise.” This difference in implicit memory probably occurred because as you read the sentence, the concept of “library” and perhaps “book” was primed, even though they were never mentioned explicitly. Once a concept is primed, it influences our behaviours. For example, if you are primed by the information you receive in the news, it may, unbeknownst to you, prompt your decision-making later on about buying a product, voting for a candidate, and so on.

Our everyday behaviours are influenced by priming in both positive and negative ways. When people are exposed to race-related news stories in the media, it can activate racial stereotypes in their minds. However, teaching people to be critical of what they see in the media and showing them news stories that challenge stereotypes can help reduce racism and counteract this priming effect (Ramasubramanian, 2007).

Semantic Knowledge and Schemas

Memories that are stored in LTM are not isolated but rather are linked together into categories — networks of associated memories that have features in common with each other. Forming categories, and using categories to guide behaviour, is a fundamental part of human nature. Associated concepts within a category are connected through spreading activation, which occurs when activating one element of a category activates other associated elements. For instance, because favourable traits are associated in a category, reminding people of the word “honest” will help them remember the word “kind.” In other words, if they have just remembered the word “honest,” spreading activation means they are more likely to remember the word “kind” than they are to remember a word in a different category such as “stupid” (Srull & Wyer, 1989). We can take advantage of spreading activation as students: we are able to link new words to previously learned concepts with a larger knowledge base because there is more capacity to activate concepts within a category.

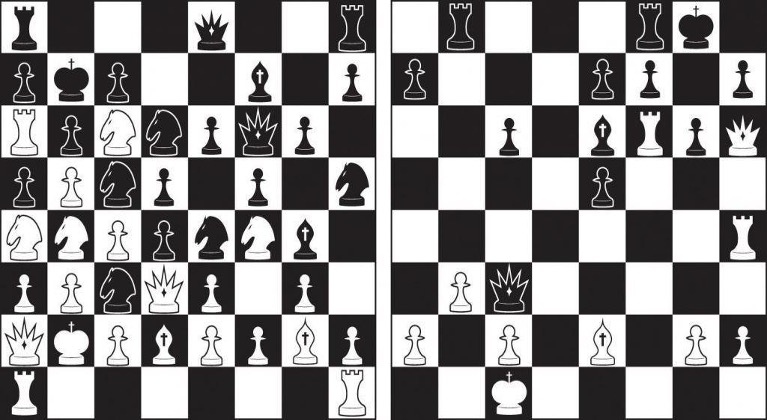

Experts rely on prior knowledge to help them organise complex information. William Simon and Herbert Chase (1973) showed chess experts and chess novices various positions of pieces on a chessboard for a few seconds each. The experts did a lot better than the novices in remembering the positions because they were able to see the “big picture.” They did not have to remember the position of each of the pieces individually but chunked the pieces into several larger layouts. However, when the researchers showed both groups random chess positions — positions that would be very unlikely to occur in real games — both groups did equally poorly, because in this situation the experts lost their ability to organise the layouts.

Semantic knowledge is sometimes referred to as schemas — clusters of knowledge in semantic memory that help us organise information. We have schemas about objects (e.g., a triangle has three sides and may take on different angles), about people (e.g., Sam is friendly, likes to golf, and always wears sandals), about events (e.g., the particular steps involved in ordering a meal at a restaurant), and about social groups (i.e., stereotypes). Schemas can be used as mental shortcuts; if seeing someone or something activates a schema, we may think we know more about the thing or person specifically than we actually do.

Schemas are important in part because they help us remember new information by providing an organisational structure for it. Read the following paragraph, and then try to write down everything you can remember:

“The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, that is the next step; otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run, this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first, the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell. After the procedure is completed, one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then, they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually, they will be used once more, and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.” (Bransford & Johnson, 1972, p. 722)

It turns out that people’s memory for this information is quite poor. However, when they have been told ahead of time that the information describes “doing the laundry,” their memory for the material is much better. This demonstration of the role of schemas in memory shows how our existing knowledge can help us organise new information and how this organisation can improve encoding, storage, and retrieval.

Autobiographical Memory

Autobiographical memory refers to one’s memory for specific experiences from their daily life. Traditionally, autobiographical memory is considered to be one type of episodic memory. However, in a broad sense, autobiographical memory may also include one’s self-knowledge (also called autobiographical knowledge) and memories of generic, non-specific events. Autobiographical memory serves at least three important functions (Williams et al., 2008): It allows us to use our past experiences to solve current problems, to share personal stories and bond with other people, and most importantly, to develop and maintain our self-image.

Qi Wang (2016) points out that young children learn what to remember, how to remember, and why to remember it, primarily through parent-child dialogues. The development of autobiographical memory is affected by not only one’s social contexts but also their cultural dynamics.

Indeed, we constantly retain memories of our personal past based on cultural beliefs, learn about our cultural identities, and adapt to the environment shaped by our cultures. For instance, researchers have found robust evidence for the lasting impact of residential schools on Indigenous communities in Canada and how trauma can be transmitted through generations (Wilk, 2017). It is unfortunate that the pain from these schools continues to affect the current generation, leading to a crisis of youth suicides. The experiences of residential schools can go beyond mere recollection of events and become deeply ingrained in individuals’ biology, affecting the health of the next generation (Chief Moon-Riley et al., 2019). It may be a pattern of stress response that affects the adult children of survivors, causing problems in how their bodies handle stress.

Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart dedicated her career to studying historical trauma and unresolved grief among Indigenous people. Historical trauma response refers to the emotional and psychological wounds from catastrophic events faced by specific groups. This collective trauma has led to social issues like high rates of suicide and alcoholism in Indigenous communities. Historical unresolved grief is closely related, representing unexpressed pain that continues to impact individuals and communities across generations. Brave Heart developed psycho-educational group interventions rooted in Indigenous healing practices to help individuals understand the sources of their distress, connect with their cultural history, express and process their grief, and develop coping strategies to heal and build resilience. Here is a video with Dr. Brave Heart talking about her research.

Watch this video: Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart: Historical Trauma in Native American Populations (31 minutes)

“Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart: Historical Trauma in Native American Populations” video by Smith College School for Social Work is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Spatial Memory

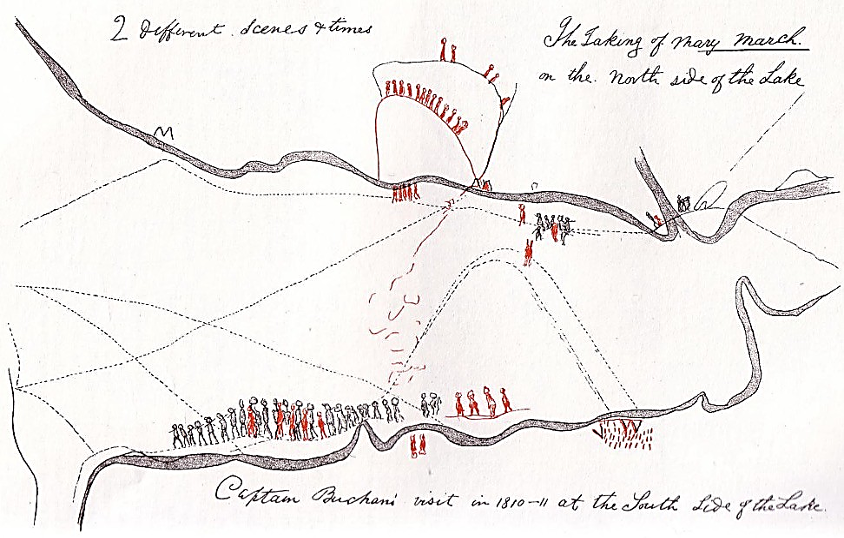

An important job of our memory system is to keep track of locations where our experiences happen; they act as anchors for our personal memories. Consider this: all of your cherished personal memories happened in a particular place and it is difficult to imagine the event without it. In order to recall a location later, it must be encoded quickly at the time an event is happening, along with many other details you will need in order to recall the experience later. Because we are mobile creatures, the places where memories happen are constantly changing, so our memory systems are designed to create mental maps quickly. Not only is spatial memory encoded quickly, but it is also quite accurate. The image below was drawn from memory by Shanawdithit, an Indigenous woman who was thought to be the last known survivor of the Beothuk people, an Indigenous population who formerly inhabited territory colonially known as Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada). Although Shanawdithit had no prior experience with pen and paper, she was able to recreate the physical space with detailed accuracy using her memory.

Our cognitive map-making abilities are the basis of some tried and true memory enhancing techniques. The method of loci approach, or memory palace, was used by the ancient Greeks and Romans to remember long speeches. To do this, the individual forms mental images of words or objects and places them in specific locations along a familiar route. To retrieve this information, the individual takes a mental stroll through the familiar space. Memory contest champions use this technique, which can be easily mastered with some practice. In fact, after covering the American Memory Championship as a journalist, Joshua Foer practiced this and other memory techniques and returned to win the competition the following year. Joshua Foer is a science writer who ‘accidentally’ won the US Memory Championships. Watch his TED Talk, Feats of Memory Anyone Can Do, in which he explains the method of loci approach.

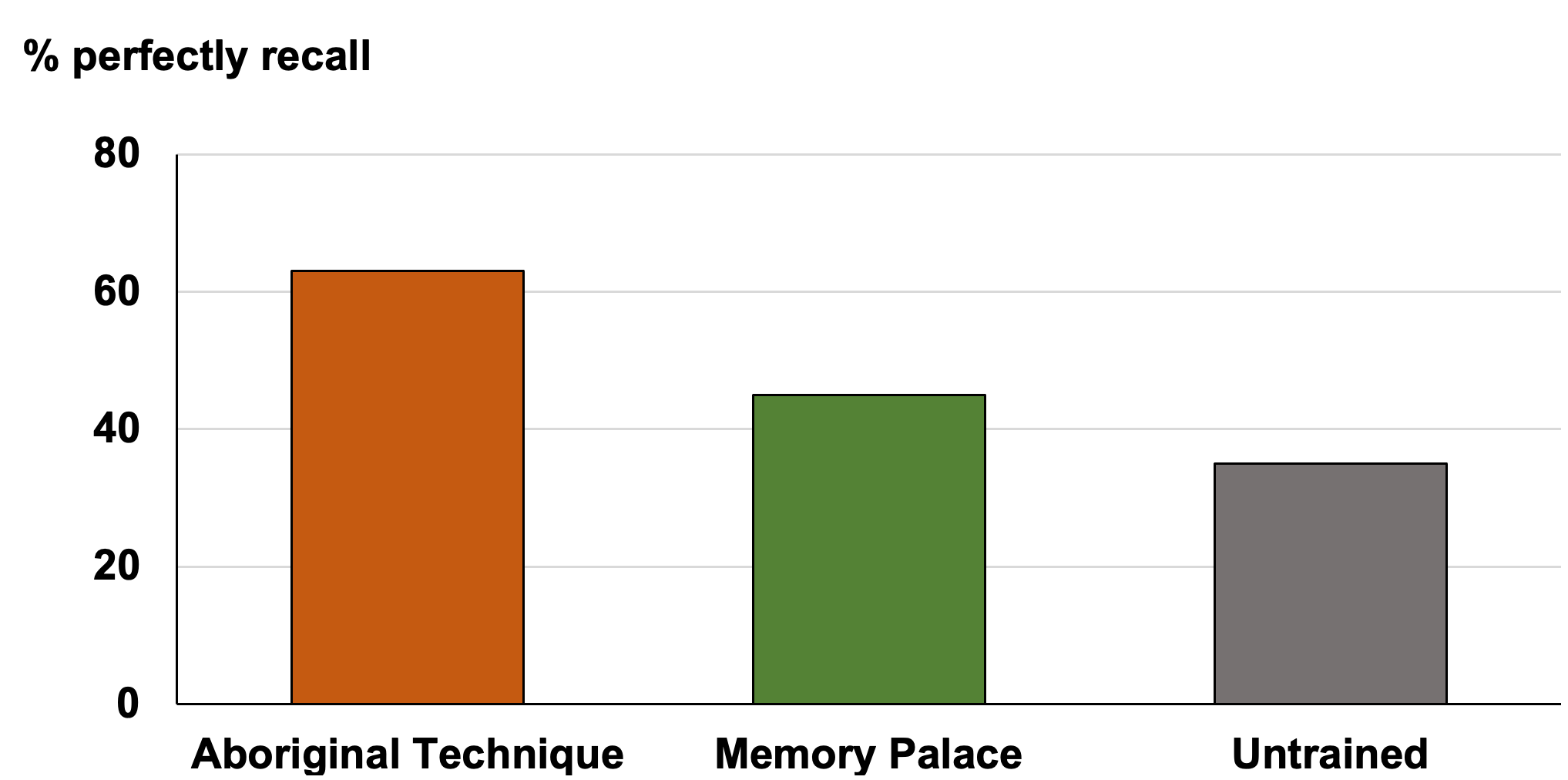

An even older spatial memory technique used by Indigenous populations living in Australia (i.e., Aboriginal peoples living in Australia) involves creating a story in an actual physical space and using elements in the environment as part of the narrative. Among Aboriginal populations living in Australia, these stories tend to remain consistent over decades and centuries. Likely, because the stories are diligently learned, protected and “passed down” by Aboriginal Elders. One study compared this Aboriginal spatial memory technique to the memory palace technique as a way for medical students to learn the cellular reactions of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Reser et al., 2021). Their findings indicate that the incorporation of spatial memory skills into education could help improve memorisation, because they take advantage of our natural ability for encoding and storing spatial information.

Further categorisations have been explored in the study of long-term memory. For instance, in contrast to retrospective memory, which involves remembering people, events, or words that have been encountered in the past, prospective memory is a form of memory that involves remembering to perform a planned action or recall a planned intention at some future point in time (Burgess & Shallice, 1997). Older adults usually perform worse than younger individuals in prospective memory tasks (Henry et al., 2004; Uttl, 2008). As individuals age, they may encounter increased challenges in remembering to perform tasks at a future time, such as taking medications at specific designated times, or setting out the garbage cans on the appointed day. In parallel to explicit and implicit memory, researchers also investigate the distinction between involuntary memory (e.g., cues encountered in everyday life evoke recollections of the past without conscious effort; Berntsen, 1996) and voluntary memory (e.g., a deliberate effort to recall what you have learned about spatial memory). In addition to remembering information itself, the ability to accurately recall the source of learned information, referred to as source memory or source monitoring, is also very important, because the source of information can influence people’s judgment of the credibility of information and their decision-making (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Image Attributions

Figure ME.12. Figure 10.5 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure ME.13. From Vanished Peoples: The Archaic Dorset & Beothuk People of Newfoundland by P. Such, 1978, NC Press. Public domain image 1829 by Shanawdithit.

Figure ME.14. Australian Aboriginal memory technique is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).