Chapter 15. Psychology in Our Social Lives

Making Sense of Ourselves and Others

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate Reading Time: 29 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the challenges of forming judgments about other people, such as different forms of prejudice and attribution errors

- Explain how attitudes change, and how they relate to behaviour

Social cognition refers to the process of understanding what people are thinking and feeling, and why they do the things they do. It helps us make sense of social situations, like why someone might be happy or sad, and how we can interact with others in a way that makes sense to them. One important aspect of social cognition involves forming impressions of other people. Making these judgments quickly and accurately guides our behaviour and helps us to interact appropriately with others. Understanding why someone may treat us unfairly allows us to address and resolve issues; figuring out how to positively influence people’s attitudes can contribute to making the world a better place.

Perceiving Others

Our initial judgments of others are based in large part on what we see. Although it may seem inappropriate or shallow, we are strongly influenced by the physical features of other people — particularly their gender, race, age, and our perception of their physical attractiveness. In many cases physical attractiveness is the most important determinant of our initial liking for other people (Walster et al., 1966). Infants who are only a year old prefer to look at faces that adults consider to be attractive than at those considered to be unattractive (Langlois et al., 1991). Evolutionary psychologists have argued that our belief that “what is beautiful is also good” may be because we use attractiveness as a cue for health; people whom we find more attractive may also have been healthier, evolutionarily (Zebrowitz et al., 2003). Psychologists have identified three physical indicators of health:

- Youth. Leslie Zebrowitz and colleagues (1991, 2009) have found that people who have baby faces are seen as more attractive than people who are not baby-faced. The baby-face features include large, round, and widely spaced eyes, a small nose and chin, prominent cheekbones, and a large forehead.

- Symmetry. People with symmetrical faces are perceived as healthier than asymmetrical faces. However, facial asymmetry does not seem to be related to their actual health (Rhodes et al., 2001).

- Averageness. Although you might think that we would prefer faces that are unusual or unique, in fact the opposite is true. Judith Langlois and Lori Roggman (1990) showed university students the faces of men and women. The faces were composites made up of the average of 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 faces. The researchers found that the more faces that were averaged into the stimulus, the more attractive it was judged.

People across different cultures tend to like faces that look young, symmetrical, and average. However, each culture might also have its own ideas about what makes a face attractive. For example, in modern Western cultures, people prefer those who have little excess fat (Crandall et al., 2009). Other cultures do not show such a strong preference for thinness (Sugiyama, 2005). The need to be thin to be attractive is particularly strong for women. The desire to maintain a low body weight can lead to low self-esteem, eating disorders, and other health-impairing behaviours. However, the norm of thinness has not always been in place; the preference for women with slender, masculine, and athletic looks has become stronger over the past 50 years.

Sterotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

We frequently use people’s appearances to form our judgments about them and to determine our responses to them. The tendency to attribute personality characteristics to people on the basis of their external appearance or their social group memberships is known as stereotyping. Our stereotypes about physically attractive people lead us to see them as more dominant, sexually warm, mentally healthy, intelligent, and socially skilled than we perceive physically unattractive people (Langlois et al., 2000). The physically attractive are more successful on job interviews (Hosoda et al., 2003). They even receive lighter sentences in court judgments than their less attractive counterparts (Zebrowitz & McDonald, 1991). In addition to stereotypes about physical attractiveness, we also regularly stereotype people on the basis of their group membership.

Prejudice is a negative attitude and feeling toward an individual based solely on their membership in a particular social group. Can you think of a prejudiced attitude you have held toward a group of people? How did your prejudice develop? Prejudice often begins with overgeneralising a stereotype, where we apply a stereotype to everyone in that group. For example, someone holding prejudiced attitudes toward older adults, may believe that older adults are slow and incompetent (Cuddy et al., 2005), even though many individuals of advanced age are in fact lively and intelligent. Another example of a well-known stereotype involves beliefs about racial differences among athletes. Black male athletes are often believed to be more athletic, yet less intelligent, than their white male counterparts (Hodge et al., 2008). These beliefs persist despite a number of high-profile examples to the contrary. Sadly, such beliefs often influence how these athletes are treated by others and how they view themselves and their own capabilities.

Some stereotypes may be accurate in part. Research has found, for instance, that attractive people are actually more sociable, more popular, and less lonely than less attractive individuals (Langlois et al., 2000). Consistent with the stereotype that women are “emotional,” women are, on average, considered to be more empathic and tuned in to the emotions of others than men are (Hall & Mast, 2008). Group differences in personality traits may occur, in part, because people act toward others on the basis of their stereotypes, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. A self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when our expectations about the personality characteristics of others lead us to behave toward those others in ways that make those beliefs come true. If I believe a stereotype that attractive people are friendly, then I may act in a friendly way toward people who are attractive. This friendly behaviour may be reciprocated by the attractive person, and if many other people also engage in the same positive behaviours with the person, in the long run they may actually become friendlier.

Sometimes people will act on their prejudiced attitudes toward a group of people. Discrimination is negative action toward an individual as a result of holding negative beliefs (stereotypes) and negative attitudes (prejudice) about a particular group. People often treat the target of their prejudice poorly, for example, excluding older adults from their circle of friends due to the prejudice described above. In the late 1880s, Mary Whiton Calkins, a psychologist, faced gender discrimination. Even though Harvard, where she studied, didn’t accept women, she got special permission to attend graduate seminars. She excelled in her studies under the renowned psychologist William James, meeting all the PhD requirements and earning praise as “one of the strongest professors of psychology in this country” by psychologist Hugo Münsterberg. Unfortunately, Harvard denied Calkins a PhD solely because she was a woman (Harvard University, 2019). Have you ever been the target of discrimination? If so, how did this negative treatment make you feel?

| Item | Function | Connection | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stereotype | Cognitive; thoughts about people | Overgeneralised beliefs about people may lead to prejudice | “Toronto Maple Leafs fans are arrogant and obnoxious.” |

| Prejudice | Affective; feelings about people | Feelings may influence treatment of others, leading to discrimination. | “I hate Leafs fans; they make me angry.” |

| Discrimination | Behaviour; treatment of others | Holding stereotypes and harbouring prejudice may lead to excluding, avoiding, and biased treatment of group members. | “I would never hire nor become friends with a person if I knew he or she were a Leafs fan.” |

Even if attractive people are on average friendlier than unattractive people, not all attractive people are friendlier than all unattractive people. Even if women are, on average, more emotional than men, not all men are less emotional than all women. Social psychologists believe that it is better to treat people as individuals, rather than rely on our stereotypes and prejudices, because stereotyping and prejudice are always unfair and often inaccurate. Furthermore, many of our stereotypes and prejudices occur outside of our awareness, to the extent that we do not even know that we are using them. You might want to test your own stereotypes and prejudices by completing the Implicit Association Test. It contributes to the study of unconscious stereotyping in areas like religion, disability, gender, sexuality, weight, race, age, and others.

Common types of prejudice in modern society

We may spot different forms of prejudice and discrimination. Below are some common types of prejudice in modern society.

- Racism. Racism exists for many racial and ethnic groups. For example, Blacks are significantly more likely to have their vehicles searched during traffic stops than whites, particularly when Blacks are driving in predominantly white neighbourhoods, a phenomenon often termed “DWB” or “driving while Black” (Rojek, Rosenfeld, & Decker, 2012). Mexican Americans and other Latino groups also are targets of racism from the police and other members of the community. For example, when purchasing items with a personal check, Latino shoppers are more likely than white shoppers to be asked to show formal identification (Dovidio et al., 2010).

- Sexism. Common forms of sexism in modern society include gender role expectations. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing. Women often are disliked for violating their gender role. Women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions (Ceci & Williams, 2011). Research by Laurie Rudman (1998) finds that when female job applicants self-promote, they are likely to be viewed as competent, but they may be disliked and are less likely to be hired because they violated gender expectations for modesty. Have you ever experienced or witnessed sexism? Think about your family members’ jobs or careers. Why do you think there are differences in the jobs women and men have, such as more women nurses but more male surgeons (Betz, 2008)?

Figure SL.2. The National Guard. Women now have many jobs previously closed to them, though they still face challenges in male-dominated occupations. - Ageism. Think of expectations you hold for older adults. How could someone’s expectations influence the feelings they hold toward individuals from older age groups? In some cultures, like Indigenous, Asian, Latino, and African American cultures, it’s a tradition to treat older adults with respect and honour. However, a common ageist attitude toward older adults is that they are incompetent, less attractive, physically weak, and slow. E-Shien Chang and colleagues (2020) studied ageism over a 40-year-plus period from various countries. Their results suggest that when you are over 50, you will more likely be denied access to health services and work opportunities. Ageism can also occur toward younger adults. Does society expect younger adults to be immature and irresponsible? Michelle Raymer and colleagues (2017) examined ageism against younger workers. They discovered that older workers tend to have negative views of younger workers, thinking they have more work-related issues like incompetence.

- Homophobia. Homophobia is a widespread prejudice that is tolerated by many people (Herek, 2009). Negative feelings often result in discrimination, such as the exclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LBGTQ+) people from social groups and the avoidance of LGBTQ+ neighbours and co-workers. This discrimination also extends to employers deliberately declining to hire qualified LGBTQ+ job applicants. Have you experienced or witnessed homophobia? If so, what stereotypes, prejudiced attitudes, and discrimination were evident?

Overcoming stereotypes and prejudice

We may be evolutionarily disposed to stereotyping. Because our primitive ancestors needed to accurately separate members of their own kin group from those of others, categorising people into “us” (i.e., the ingroup) and “them” (i.e., the outgroup) was useful and even necessary (Neuberg et al., 2010). We might use stereotypes, but it doesn’t mean we should. Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination can make it hard for some to contribute to society. In Canada, it’s a legal requirement to overcome prejudices, according to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982.

Prejudice can be reduced. Some people are more likely to confront and control their stereotypes and prejudices whereas others apply them more freely (Czopp et al., 2006). We can lessen stereotypes and prejudices by making friends with people from different groups and practicing not using stereotypes, and through education (Hewstone, 1996). For example, intergroup contact has been found to reduce prejudice, but contact by itself is not enough (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Groups should experience real chances to collaborate on goals and activities they both find important (Molina, et al., 2016). The shift from an “us versus them” to a “we” thinking requires mutual trust and empathy.

Making Causal Attributions of Behaviour

Attribution refers to the process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behaviour. If Frank hits Joe, we might wonder if Frank is naturally aggressive or if perhaps Joe had provoked him. If Leslie leaves a big tip for the waitress, we might wonder if she is a generous person or if the service was particularly excellent.

Sometimes we may decide that the behaviour was caused primarily by the person; this is called making a dispositional attribution. At other times, we may determine that the behaviour was caused primarily by the situation; this is called making a situational attribution. Ultimately, we may decide that the behaviour was caused by both the person and the situation.

While people are pretty good at explaining their own and others’ behaviour, they are far from perfect. We often make a mistake when judging ourselves by thinking positively about the reasons behind our actions. This is called self-serving bias. Suppose you did well on a test. You will probably attribute that success to personal causes (e.g., “I’m smart” or “I studied really hard”). But if you do poorly on the test, you are more likely to make situational attributions (e.g., “The test was hard” or “I had bad luck”).

Another common mistake is called the fundamental attribution error. It occurs when we try to attribute other people’s behaviour. Instead of considering the situation, we quickly think it’s about their personality. For example, we are more likely to say, “Leslie left a big tip, so she must be generous” than “Leslie left a big tip, but perhaps that was because the service was really excellent.” An important moral about perceiving others applies here: we should not be too quick to judge other people. It’s common to think poor people are lazy or that harsh words mean someone is unfriendly. But these attributions may overemphasise the role of the person and increase the tendency to blame the victim (Tennen & Affleck, 1990). Sometimes people are lazy and rude, but these people may also be influenced by the situation in which they find themselves. Poor people may find it more difficult to get work and education because of the environment they grow up in. People may say rude things because they are feeling threatened or are in pain.

When you find yourself making strong dispositional attributions for the behaviours of others, stop and think more carefully. Would you want other people to make personal attributions for your behaviour in the same situation, or would you prefer that they more fully consider the situation surrounding your behaviour? Are you perhaps making the fundamental attribution error?

Research shows cultural differences in attributions. In individualistic cultures like the US and the UK, people tend to make the fundamental attribution error. They focus on individual achievement and autonomy, thinking a person’s disposition is the main reason for their behaviour. By contrast, in collectivistic cultures like the east Asian countries, the focus is on the group more than on the individual (Nisbett et al., 2001). They tend to take into account both situational and cultural influences on behaviour. Therefore, people from collectivistic cultures are less likely to commit the fundamental attribution error (Triandis, 2001).

Changing Attitudes

Attitudes refer to our relatively enduring evaluations of people and things. Attitudes are important because they frequently predict behaviour. If we know that a person has a more positive attitude toward Frosted Flakes than toward Cheerios, then we will naturally predict that they will buy more Frosted Flakes when grocery shopping. Because attitudes often predict behaviour, people who wish to change behaviour frequently try to change attitudes through the use of persuasive communications.

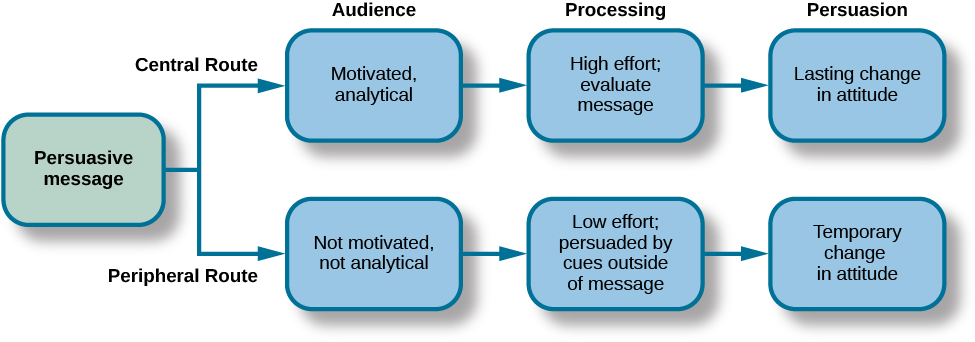

There are two main routes that play a role in delivering a persuasive message: central and peripheral.

Central Route

The central route is logic driven and uses data and facts to convince people of an argument’s worthiness. For example, a car company seeking to persuade you to purchase their model will emphasise the car’s safety features and fuel economy. This is a direct route to persuasion that focuses on the quality of the information. In order for the central route of persuasion to be effective in changing attitudes, the argument must be strong and, if successful, will result in lasting attitude change. The central route to persuasion works best when the audience is analytical and willing to engage in processing the information. From an advertiser’s perspective, what products would best be sold using the central route to persuasion? What audience would most likely be influenced to buy the product? One example is buying a computer. It is likely that small business owners might especially be influenced by the focus on the computer’s qualities and features such as processing speed and memory capacity.

Peripheral Route

The peripheral route is an indirect route that uses peripheral cues to associate a positive feeling with the message. Instead of focusing on the facts and a product’s quality, the peripheral route relies on association with positive characteristics such as celebrity endorsement. For example, having a popular athlete advertise athletic shoes is a common method used to encourage young adults to purchase the shoes. This route to attitude change does not require much effort or information processing. This method of persuasion may promote positivity toward the message or product, but it typically results in less permanent attitude change. The audience does not need to be analytical or motivated to process the message. In fact, a peripheral route to persuasion may not even be noticed by the audience, for example in the strategy of product placement. Product placement refers to putting a product with a clear brand name or brand identity in a TV show or movie to promote the product. For example, one season of the reality series American Idol prominently showed the panel of judges drinking out of cups that displayed the Coca-Cola logo. What other products would best be sold using the peripheral route to persuasion? Another example is clothing: A retailer may focus on celebrities that are wearing the same style of clothing.

Successful Persuasion Strategies

Researchers have tested many persuasion strategies that are effective in selling products and changing people’s attitude and behaviours. One effective strategy is the foot-in-the-door technique. First, the persuader gets a person to agree to a small request, only to later ask for a larger favour. The foot-in-the-door technique was demonstrated in a study by Freedman and Fraser (1966) in which participants who agreed to post a small sign in their yard or sign a petition were more likely to agree to put a large sign in their yard than people who declined the first request.

A variation of foot-in-the-door is called low-balling technique. The persuader starts with a favourable request. After the audience agrees, they reveal some unfavourable details or additional conditions. Cialdini et al. (1978) demonstrated the effect of low-balling in a class of first-year psychology students. He asked them to participate in a study on cognition, and that they would meet at 7:00 in the morning. Asked directly, only 1/4 of the students were willing to participate. When the meeting time wasn’t initially mentioned, more than half of the students agreed to participate. Later, when they were informed about the early time, most students who had already agreed didn’t change their minds.

Alternatively, the persuader may start with a large request that will certainly be turned down, then present a smaller, more feasible request (which is the true request). People tend to agree to the second, smaller request. This is called door-in-the-face technique. Cialdini et al (1975) asked college students if they were willing to supervise a group of teenagers on a day trip to the zoo. When directly asked, over 80% refused. However, when they began with a challenging request, asking for a commitment of two years where nobody agreed, the real request came next, seeming much more reasonable compared to the first one. As a result, half of the students agreed to supervise the zoo trip.

One difficulty of persuasion is that attitudes do not always predict the actual behaviour. Behaviours are more likely to be consistent with attitudes when the social situation in which the behaviour occurs is similar to the situation in which the attitude is expressed (Ajzen, 1991). Imagine the case of Magritte, a 16-year-old high school student, who tells her parents that she hates the idea of smoking cigarettes. How sure are you that Magritte’s attitude will predict her behaviour? Would you be willing to bet that she’d never try smoking when she’s out with her friends? The problem here is that Magritte’s attitude is being expressed in one social situation (i.e., when she is with her parents) whereas the behaviour (i.e., trying a cigarette) would occur in a very different social situation (i.e., when she is out with her friends). Magritte’s friends might be able to convince her to try smoking by applying peer pressure.

You might expect that our attitudes predict what we do, but it can be surprising that what we do can also affect our attitudes. It makes sense that if I like Frosted Flakes I’ll buy them, because my positive attitude toward the product influences my behaviour. However, my attitude toward Frosted Flakes may also become more positive if I decide — for whatever reason — to buy some.

Behaviours influence attitudes, in part, through the process of self-perception. Self-perception occurs when we use our own behaviour as a guide to help us determine our own thoughts and feelings (Bem, 1972). In one demonstration of the power of self-perception, Gary Wells and Richard Petty (1980) assigned their research participants to shake their heads either up and down or side to side as they read newspaper editorials. The participants who had shaken their heads up and down later agreed with the content of the editorials more than the people who had shaken them side to side. In other words, the participants used their own head-shaking behaviours to determine their attitudes about the editorials.

Persuaders may use the principles of self-perception to change attitudes. Imagine someone decides to cut back on drinking. Instead of saying, “I’m quitting forever,” they might start by saying, “I’m going to take a break for a week.” As they successfully avoid drinking for that week, they begin to see themselves as someone who can control their drinking. This positive self-perception may encourage them to extend the break, eventually leading to a longer-term decision to quit drinking altogether.

Behaviour also influences our attitudes through a more emotional process known as cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance refers to the discomfort we feel when we act in ways that we think are wrong (Festinger, 1957). If we feel that we have wasted our time or acted against our own moral principles, we experience dissonance and may change our attitudes about the behaviour to reduce this discomfort. In one demonstration of the power of cognitive dissonance, Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills (1959) studied whether the discomfort from an initiation process could explain how committed students felt to a group. Female university students volunteered for a psychology of sex discussion group. Some were told to do an embarrassing initiation (reading explicit content in public), while others were spared. Later, everyone listened to a dull group conversation. The results showed that those with the embarrassing initiation reported liking the group more. The effort creates dissonant cognitions (e.g., “I did all this work to join the group”), which are then justified by creating more consonant ones (e.g., “Okay, this group is really pretty fun”).

Generally speaking, when people put in more effort, they become more committed. When we put in effort for something — an initiation, a big purchase price, or even some of our precious time — we will likely end up liking the activity more than we would have if the effort had been less; not doing so would lead us to experience the unpleasant feelings of dissonance. After we buy a product, we convince ourselves that we made the right choice because the product is excellent. If we hurt someone else’s feelings, we may even decide that they are bad people who deserve our negative behaviour. To escape from feeling poorly about themselves, people may believe that “If I had it all to do over again, I would not change anything important.”

Image Attributions

Figure SL.2. Unnamed image by The National Guard is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure SL.3. Homeless Man by Matthew Woitunski is used under a CC BY 3.0 license; Homeless New York 2008 by JMSuarez is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure SL.4. Figure 12.4 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License and contains modifications of the following works: credit a: modification of Danau Tamblingan, family picnic by Arian Zwegers; and (b) modification of China Tuanshan – women playing Mahjongg by Anja Disseldorp which are both licensed under a CC BY 2.0 License.

Figure SL.5. Figure 12.15 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure SL.6. (a) Vote Obama 08 by Mykl Roventine is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license. (b) hope-ium” by “shutterblog” is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).