Chapter 19. Treatment of Psychological Disorders

Mental Health Treatment: Past and Present

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 16 minutes

Treatment in the Past

For much of history, the mentally ill have been treated very poorly. It was believed that mental illness was caused by demonic possession, witchcraft, or an angry god (Szasz, 1960). For example, in medieval times, abnormal behaviours were viewed as a sign that a person was possessed by demons. If someone was considered to be possessed, there were several forms of treatment to release spirits from the individual. The most common treatment was exorcism, often conducted by priests or other religious figures: Incantations and prayers were said over the person’s body, and she may have been given some medicinal drinks. Another form of treatment for extreme cases of mental illness was trephining: A small hole was made in the afflicted individual’s skull to release spirits from the body. Most people treated in this manner died. In addition to exorcism and trephining, other practices involved execution or imprisonment of people with psychological disorders. Still others were left to be homeless beggars. Generally speaking, most people who exhibited strange behaviours were greatly misunderstood and treated cruelly. The prevailing theory of psychopathology in earlier history was the idea that mental illness was the result of demonic possession by either an evil spirit or an evil god because early beliefs incorrectly attributed all unexplainable phenomena to deities deemed either good or evil.

From the late 1400s to the late 1600s, a common belief perpetuated by some religious organisations was that some people made pacts with the devil and committed horrible acts, such as eating babies (Blumberg, 2007). These people were considered to be witches and were tried and condemned by courts — they were often burned at the stake. Worldwide, it is estimated that tens of thousands of mentally ill people were killed after being accused of being witches or under the influence of witchcraft (Hemphill, 1966).

By the 18th century, people who were considered odd and unusual were placed in asylums (Figure PY.1). Asylums were the first institutions created for the specific purpose of housing people with psychological disorders, but the focus was on ostracising them from society rather than treating their disorders. Often these people were kept in windowless dungeons, beaten, and chained to their beds, with little to no contact with caregivers.

In the late 1700s, a French physician, Philippe Pinel, argued for more humane treatment of the mentally ill. He suggested that they be unchained and talked to, and that’s just what he did for patients at La Salpêtrière in Paris in 1795 (Figure PY.2). Patients benefited from this more humane treatment, and many were able to leave the hospital.

In the 19th century, Dorothea Dix led reform efforts for mental health care in the United States (Figure PY.3). She investigated how those who are mentally ill and poor were cared for, and she discovered an underfunded and unregulated system that perpetuated abuse of this population (Tiffany, 1891). Horrified by her findings, Dix began lobbying various state legislatures and the US Congress for change (Tiffany, 1891). Her efforts led to the creation of the first mental asylums in the United States.

Despite reformers’ efforts, however, a typical asylum was filthy, offered very little treatment, and often kept people for decades. At Willard Psychiatric Center in upstate New York, for example, one treatment was to submerge patients in cold baths for long periods of time. Electroshock treatment was also used, and the way the treatment was administered often broke patients’ backs; in 1943, doctors at Willard administered 1,443 shock treatments (Willard Psychiatric Center, 2009). (Electroshock is now called electroconvulsive treatment, and the therapy is still used, but with safeguards and under anaesthesia. A brief application of electric stimulus is used to produce a generalised seizure. Controversy continues over its effectiveness versus the side effects.) Many of the wards and rooms were so cold that a glass of water would be frozen by morning (Willard Psychiatric Center, 2009). Willard’s doors were not closed until 1995. Conditions like these remained commonplace until well into the 20th century.

Starting in 1954 and gaining popularity in the 1960s, antipsychotic medications were introduced. These proved a tremendous help in controlling the symptoms of certain psychological disorders, such as psychosis. Psychosis was a common diagnosis of individuals in mental hospitals, and it was often evidenced by symptoms like hallucinations and delusions, indicating a loss of contact with reality. Then in 1963, Congress passed and John F. Kennedy signed the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act, which provided federal support and funding for community mental health centres (National Institutes of Health, 2013). This legislation changed how mental health services were delivered in the United States. It started the process of deinstitutionalisation — the closing of large asylums — by providing for people to stay in their communities and be treated locally. In 1955, there were 558,239 severely mentally ill patients institutionalised at public hospitals (Torrey, 1997). By 1994 (by percentage of the population) there were 92% fewer hospitalised individuals (Torrey, 1997).

Mental Health Treatment Today

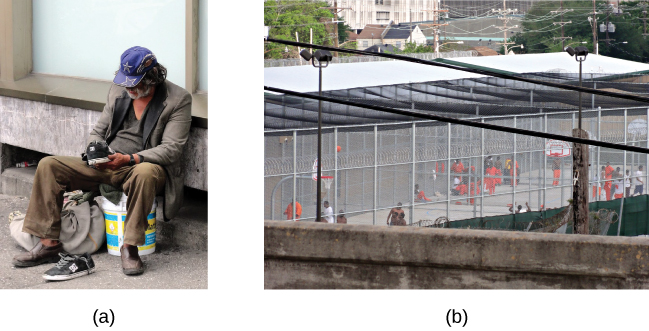

Today, there are community mental health centres across the nation. They are located in neighbourhoods near the homes of clients, and they provide large numbers of people with mental health services of various kinds and for many kinds of problems. Unfortunately, part of what occurred with deinstitutionalisation was that those released from institutions were supposed to go to newly created centres, but the system was not set up effectively. Centres were underfunded; staff was not trained to handle severe illnesses such as schizophrenia; there was high staff burnout; and no provision was made for the other services people needed, such as housing, food, and job training. Without these supports, those people released under deinstitutionalisation often ended up homeless. Even today, a large portion of the homeless population is considered to be mentally ill (Figure PY.4). Statistics show that 26% of homeless adults living in shelters experience mental illness (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD], 2011).

Mental Health and the Corrections System: Indigenous people over-represented

Another group of the mentally ill population is managed by the corrections system. In Canadian prisons, the prevalence of mental health disorders is notably higher than in the general population, affecting a significant portion of the incarcerated individuals. Studies indicate that about 25% of men and up to 50% of women in federal custody are identified with serious mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety disorders (Sapers, 2016). The rate is particularly high among women, who are also more likely to be diagnosed with borderline personality disorder compared to their male counterparts (Beaudette & Stewart, 2016). Additionally, mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder are common among inmates; a notable presence of co-occurring substance abuse disorders complicates treatment and rehabilitation (Stewart & Wilton, 2017).

In the Canadian correctional system, Indigenous people are significantly over-represented. While Indigenous men and women represent a small fraction of the general population, they face incarceration rates much higher than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Indigenous men are incarcerated at a rate 10 times greater than that for non-Indigenous men. The rate for Indigenous women is 19 times greater than that for non-Indigenous women. These disparities are in part a result of the complex interaction of the egregious harm done by separating children from their families, the socioeconomic disadvantages due to the theft of land and resources by colonial agencies, and the cultural genocidal legacies of colonisation (Statistics Canada, 2021).

Despite the pressing need, there is a significant gap in providing adequate mental health services to Indigenous inmates. Systemic barriers and a lack of culturally appropriate interventions mean that many do not receive the care they need. Recognising these issues, various levels of government have initiated reforms aimed at acknowledging the unique circumstances of Indigenous offenders and improving mental health care within correctional facilities (Correctional Service Canada, 2019; Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2020).

Today, instead of asylums, there are psychiatric hospitals run by state governments and local community hospitals, focused on short-term care. In all types of hospitals, the emphasis is on short-term stays, with the average length of stay being less than two weeks and often only several days. This is partly due to the very high cost of psychiatric hospitalisation, which can be about $800 to $1000 per night (Stensland, Watson, & Grazier, 2012). Therefore, insurance coverage often limits the length of time a person can be hospitalised for treatment. Usually, individuals are hospitalised only if they are an imminent threat to themselves or others.

Most people suffering from mental illnesses are not hospitalised. If someone is feeling very depressed, complains of hearing voices, or feels anxious all the time, they might seek psychological treatment. A friend, spouse, or parent might refer someone for treatment. The individual might go see their primary care physician first and then be referred to a mental health practitioner.

Some people seek treatment because they are involved with the state’s child protective services — that is, their children have been removed from their care due to abuse or neglect. The parents might be referred to psychiatric or substance abuse facilities and the children would likely receive treatment for trauma. If the parents are interested in and capable of becoming better parents, the goal of treatment might be family reunification. For other children whose parents are unable to change — for example, the parent or parents who are heavily addicted to drugs and refuse to enter treatment — the goal of therapy might be to help the children adjust to foster care and/or adoption (Figure PY.5).

Some people seek therapy because the criminal justice system referred them or required them to go. For some individuals, for example, attending weekly counseling sessions might be a condition of parole. If an individual is mandated to attend therapy, they are seeking services involuntarily. Involuntary treatment refers to therapy that is not the individual’s choice. Other individuals might voluntarily seek treatment. Voluntary treatment means the person chooses to attend therapy to obtain relief from symptoms.

Psychological treatment can occur in a variety of places. An individual might participate in traditional healing methods (e.g., sweat lodge ceremonies, herbal medicines, smudging, and talking circles) facilitated by and under the guidance of Elders or traditional healers. An individual might go to a community mental health centre or a practitioner in private or community practice. A child might see a school counselor, school psychologist, or school social worker. An incarcerated person might receive group therapy in prison. There are many different types of treatment providers, and licensing requirements vary from state to state. Besides psychologists and psychiatrists, there are clinical social workers, marriage and family therapists, and trained religious personnel who also perform counseling and therapy.

In Canada, mental health treatment funding is supported by a combination of public health insurance, private insurance, and out-of-pocket payments. Under the Canada Health Act, which mandates accessibility and universality, provincial and territorial health insurance plans must cover medically necessary hospital and physician services, including those for mental health (Government of Canada, 2021). However, not all mental health services, especially those provided outside hospitals or by non-physicians, are covered, which may necessitate private insurance or direct payments by individuals.

The landscape of mental health coverage began evolving significantly with the introduction of policies that push for parity (equality) between mental and physical health treatments. For example, several provinces have taken steps to ensure better coverage and access to mental health services. Ontario, through its Health Insurance Plan (OHIP), provides coverage for psychiatry and some psychological therapy sessions delivered by physicians, aligning with the principles of parity where treatment for mental health issues is covered under the same terms as physical health issues (Ontario Ministry of Health, 2020).

Additionally, the Mental Health Commission of Canada advocates for consistent and equitable treatment across all types of health insurance, promoting policies that ensure mental health services are funded on par with physical health services, reflecting the approach of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in the US (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2020).

Image Attributions

Figure PY.1. Figure 16.4 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.2. Figure 16.5 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.3. Figure 16.6 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.4. Figure 16.7 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PY.5. Figure 16.8 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).