Chapter 18. Psychological Disorders

Neurodiversity

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 49 minutes

In most introductory psychology texts, including the first edition of this one, this section is entitled “Neurodevelopmental Disorders”. This terminology presents atypical brain organisation and development as disordered. All brains differ to some degree, so neurodivergence is a normal variation in the structure and function of a nervous system, even if it’s less common (Chappel & Worsley, 2021). Instead, in this chapter we will use the term neurodiversity, which was coined by autistic sociologist Judy Singer to acknowledge the diversity of neurotypes (different kinds of brain organisation and function) that can appear in a population of healthy people.

Your neurotype is present from birth to the end of your life, influencing development, cognition, sensory perception, emotional and behavioural regulation, and social behaviour, so it’s a fundamental part of who you are, guiding and informing your experience of the world. In this view, people who fall within the average range of neurotypes are neurotypical (NT), and people who exist outside of it are neurodivergent (Baumer & Frueh, 2021). In fact, the term “neurotypical” doesn’t refer to a specific neurotype, since there’s a lot of variation between the brains of neurotypical people as well.

Differences in function that result from a person’s neurotype can change over time, and some people may not be identified as neurodiverse until adulthood. This section will focus on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Keep in mind that dyslexia, dyscalculia, Down syndrome, hyperlexia, dyspraxia, Meares-Irlen Syndrome and Tourette Syndrome are often also considered to be types of neurodivergence as well.

Discussing Disability and Neurodivergence

The shift from “neurodevelopmental disorders” to “neurodiversity” reflects a change in the way we understand disability and neurodivergence. Historically, the medical model was used to define disability as defects in disabled people that should be cured or prevented (Hogan, 2019). Following this logic, poor outcomes like low employment and educational attainment are a result of disabled people’s limitations, and systemic factors that make these goals unattainable for them aren’t addressed. This means that under the medical model, disabled people are expected to overcome barriers related to disability, even if those barriers could be eliminated by making changes at a social level so that a wider variety of needs are considered. This model values the prevention of disability over the rights and wellbeing of disabled people and has even been used to argue for the prevention or “curing” of things like same-gender attraction, which are not disabilities. Even in Canada, some provinces continued to classify homosexuality as a medical disorder until 2010 (CBC News, 2010).

An alternative promoted by many disabled people is the social model, which argues that disability mostly happens when systemic social factors disadvantage people with certain types of bodies and brains (Hogan, 2019; World Health Organization, 2022). Consider a person with colour deficiency trying to read a map. If the map uses colours affected by their colour deficiency, they may not be able to see the borders between countries, making the map useless to them. This person isn’t limited in their ability to understand maps, they are disadvantaged because their needs weren’t considered when the map was made. The social model isn’t meant to replace medical treatment when it’s needed, its primary goal is to improve and protect the rights of disabled people, which includes making treatment and accommodations more accessible (Guevara, 2021).

A related change involves ‘person first language’ (e.g., saying “a person with autism” instead of saying “an autistic person”), which is intended to reduce stigma by separating the condition from the person (Baumer & Frueh, 2021). This sometimes conflicts with language used by neurodivergent people; for example, many autistic people prefer identity-first language (e.g., “Autistic person”). This is meant to acknowledge that autism is a fundamental part of an autistic person, and that respecting personhood shouldn’t require the separation of a person from their neurotype (Kenny, 2015; Brown, 2011). However, not all neurodiverse people prefer identity-first language and in this text, we wish to respect differences in language preferences within these communities, with the understanding that discussions are ongoing. In this section, a mix of identity first and person first language will be used in order to acknowledge the lack of consensus and to respect both positions that may be held by neurodiverse people.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Consider the following scenarios:

Samar is writing a quiz in class. He studied for it, but he has trouble paying attention long enough to follow along with lectures, so he listened to the recording several times to review. He’s proud of himself for keeping track of the quiz date and prepping in time, as he has trouble managing and remembering dates, and has missed important dates in the past. Samar speeds through it, feeling confident. Later he realises he may have misread the instructions and missed a question. Despite studying and understanding the material, Samar doesn’t get the mark he hoped for. He visits his professor during office hours, but he misplaced his quiz, and the professor gets frustrated with him for losing focus when she is speaking to him. Outside of class, Samar struggles to connect with others because he loses track of conversations and often feels out of the loop. Samar may have primarily inattentive attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD-PI).

Alaiya is writing a quiz in class. She can’t help tapping her feet and pencil, and she nearly stands up to pace, but she knows she’ll get into trouble for doing that. She tried to study, but she was jittery, and she couldn’t focus. The feeling made her so anxious that she gave up and played video games to calm down, though she didn’t mean to. She tried to join a study group, but she had trouble following the flow of conversation, blurting things out before others had finished talking. She left the group embarrassed and worried that they thought she was rude. Despite her effort, Aliya is discouraged when she gets her mark back. She visits her professor during office hours, but there’s a line and she only manages to wait in it for a few minutes before she feels stressed and under stimulated and has to leave. Alaiya may have primarily hyperactive-impulsive ADHD (ADHD-HI).

As demonstrated above, ADHD presents in many ways. People like Samar mainly experience inattentive-type symptoms, having difficulty with sustained attention and tasks involving working memory. Others like Alaiya have more hyperactive-impulsive-type symptoms, meaning they’re motivated to seek stimulation and struggle with self-control. Others present with a combination of inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive traits (ADHD-C). Interestingly, the proportion of people with ADHD-PI increases with age, while the proportion with ADHD-HI decreases. For example, 23% of preschool age children with ADHD are primarily inattentive, but this percentage rises 75% in high school. In contrast, about 5% of preschool children are primarily hyperactive, and by high school only about 1.1% of people with ADHD are primarily inattentive. (de la Peña, 2020; Willcutt, 2012). This makes sense, since impulse control and sustained attention rely on brain systems that are still developing at this age, even for neurotypical children.

Symptoms and Traits

There are many ways that ADHD can present, so it’s likely that it represents a number of neurotypes with similar features. Since ADHD is neurodevelopmental (the growth and development of the brain and nervous system, affecting learning, communication, and behaviour), these traits are present since early childhood and exist across different settings. It’s also important to remember that some of the behavioural issues seen in people with ADHD are also seen in people experiencing trauma, sleep disorders, sensory processing disorders, and autism spectrum disorder. Some of these conditions can also coexist with ADHD. (Wolraich et al., 2019). The criteria currently used to diagnose ADHD come from the DSM-5, and involve inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Inattention

Inattentive symptoms involve difficulty keeping attention, so people with these symptoms often struggle to complete tasks, follow instructions, and use organisational skills. They may also have trouble holding attention for play or leisure activities, and may feel easily distracted (APA, 2013). Like Samar with his professor, people with these kinds of symptoms may have trouble maintaining attention in conversation or during interaction and are sometimes misunderstood as being distracted or withdrawn by others. As a result of these difficulties, they may struggle with self-esteem and social interaction, and may be reluctant to do things that require sustained attention. Some of these symptoms appear to be related to differences in sensory processing and may mean that people with these symptoms need more time to register and respond to stimuli (de la Peña, 2020).

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

People with hyperactive and impulsive symptoms may have trouble being still. For example, children with ADHD may have trouble remaining seated when it’s expected for them to do so and may have a tendency to run or climb in inappropriate situations. For teens and adults with ADHD, this is commonly experienced as an intense discomfort and restlessness, even if they can suppress the urge to move. People with these symptoms may have trouble waiting their turn in conversation, and unintentionally interrupt others. As with inattentive symptoms, people with hyperactive-impulsive symptoms may have trouble engaging in play and leisure activities in the same way that neurotypical people do, and they may feel or appear to be constantly on the go (APA, 2013). Like Aliyah in her study group, people with these traits are sometimes misunderstood by others, and can experience social difficulties as a result.

Common Traits and Experiences

ADHD and Executive Function

Executive functions are skills that allow us to direct attention, focus, plan, control our behaviour, and regulate emotions (Diamond, 2012). Executive dysfunction occurs when those skills are impaired, resulting in difficulty with time management, impulse control, and emotional regulation. Many people with ADHD experience significant impairment relating to executive function (Silverstein et al., 2018). A specific executive function associated with ADHD is working memory (WM; sometimes used interchangeably with short-term memory). This is the component of memory that allows us to hold information in mind so we can work with it in the moment. Many people with ADHD have a lower WM capacity and have more difficulty manipulating information in WM (Martinussen et al., 2005).

Given the range of skills involved in executive function, it’s not surprising that executive dysfunction could contribute to many impairments that people with ADHD experience. It isn’t yet known if executive dysfunction is a core feature of ADHD, but some studies found that executive function abilities in early childhood can predict ADHD symptoms later in life (Sjöwall et al., 2015; Brocki et al. 2009), and many people with ADHD score differently than neurotypical people on certain executive function skills (Fan & Wang, 2022). There is evidence that parts of the frontal and parietal lobes involved in executive function processes are less active in people with ADHD (Faraone et al., 2015). Further evidence can be found in people with ADHD who respond well to stimulant medication, since they’re more likely than non-responders to show reduced activity in frontal lobe areas involved in executive functions (Ogrim & Kroptov, 2019). These differences in brain activity and response to stimulants help to explain the range of ways ADHD can present.

ADHD and Attention

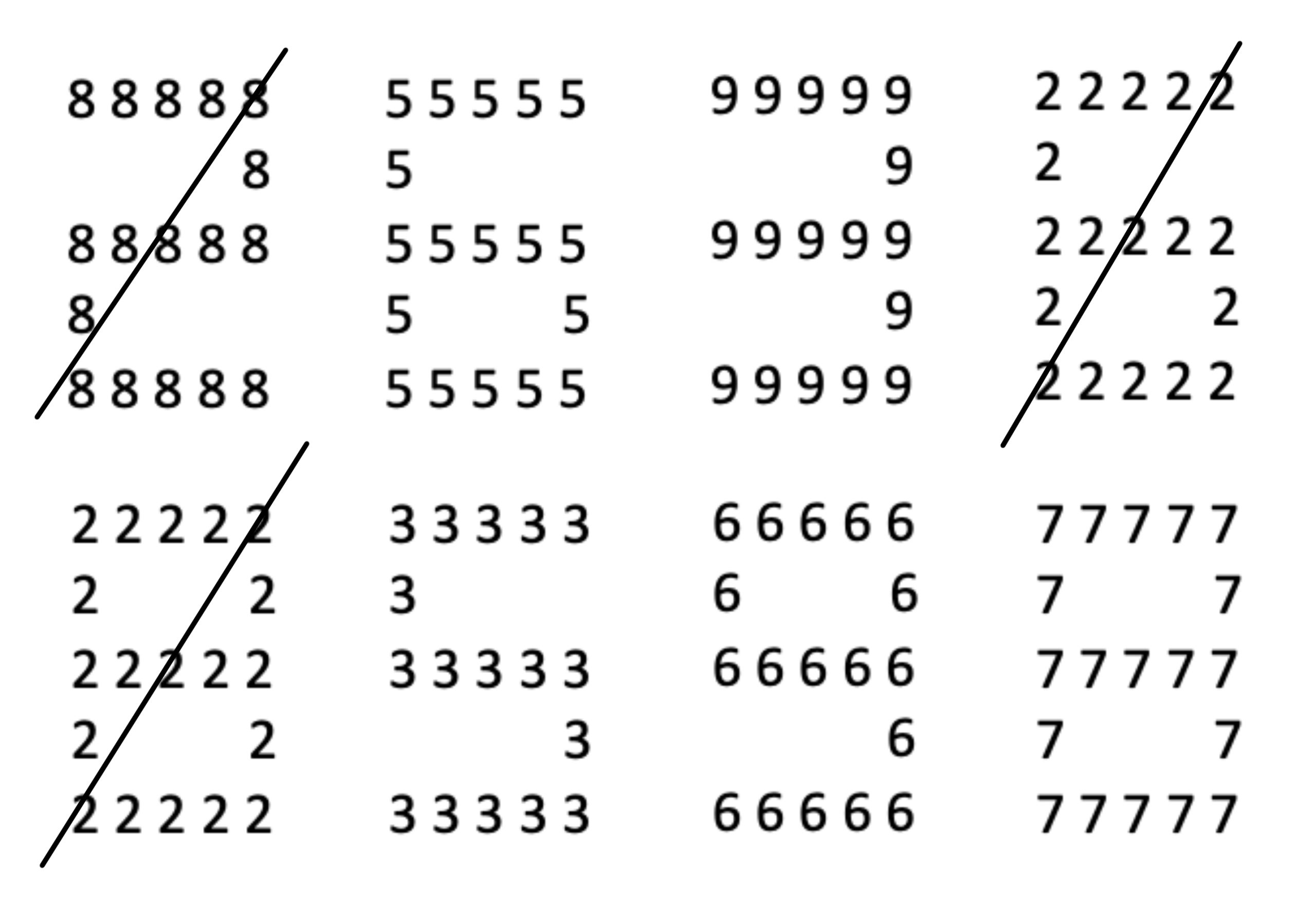

The name itself implies that ADHD is a lack of attention, but this isn’t totally accurate. Instead, the brains of people with ADHD have trouble directing attention the way neurotypical brains do, so they do more local processing, or processing of individual details that make up a big picture rather than processing the picture as a whole (Song & Hakoda, 2012), which is called global processing (Figure PD.10). As a result, someone taking a test may focus on a single multiple-choice option without reading the question itself as a whole, as Samar did. Samar had trouble focusing his attention on the expected parts of the test, and he also had trouble shifting his attention to more relevant information.

Local and global processing skills can be tested using a Compound Digit Cancelation Test (Figure PD.10). In this test, digits are arranged spatially to make up larger compound digits. Digits making up compound digits require local processing, since they can be processed as individual details. The compound digits require global processing, since the subject must combine local features to understand them. In this example, the subject was told to cross out twos and eights, whether they appeared at the local or global level. They correctly selected the two made of eights, the six made of twos, and the eight made of twos, but they missed the eight made of sevens, indicating that they may be better at local than global processing, since they more frequently identified twos and eights at the local level.

An interesting result of this difference in attention is hyperfocus, a state of increased attention and motivation directed towards a particular subject. Hyperfocus is also reported by neurotypical people, but it’s more common in autistic people and those with ADHD (Groen et al., 2020). People experiencing hyperfocus often lose their sense of time and ignore other stimuli, including bodily needs, because they can’t disengage. Hyperfocus can be a negative experience when focused on subjects that cause anxiety or which interfere with function, but it can also be enjoyable, resulting in increased productivity if focused on tasks that are beneficial to the individual (Hupfeld, 2018).

Strengths for People with ADHD

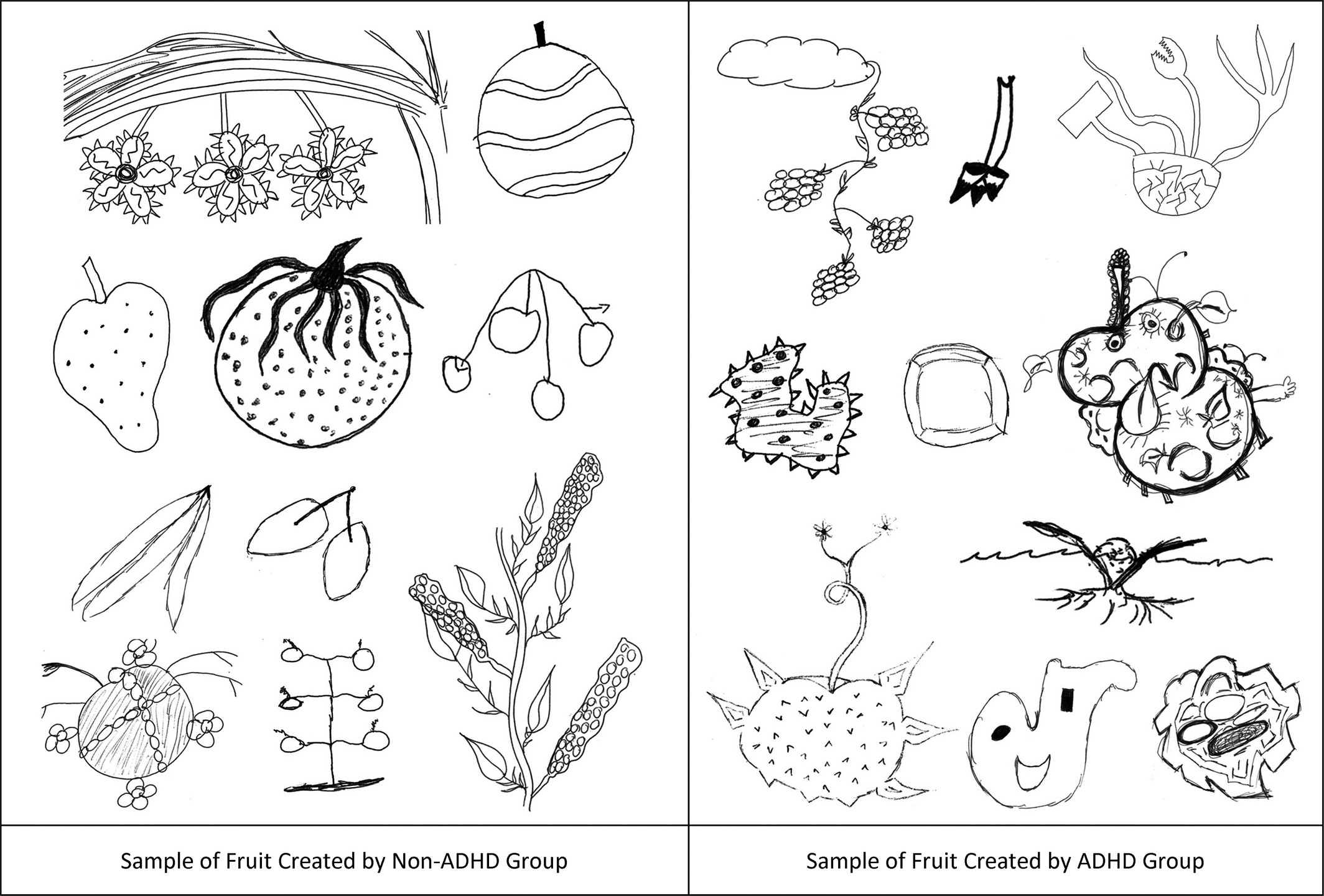

Like other kinds of neurodivergence, ADHD involves both impairments and special skills less common in neurotypical people. One strength for people with ADHD is creativity, a skill that is enhanced by the ability to combine information in new and unexpected ways. People with ADHD on average display more flexible thinking than neurotypical people on word association tasks (White & Shah, 2016), and are less restricted by existing knowledge during drawing tasks, resulting in more original creations (Figure PD.11; White, 2018). Traits like impulsivity and difficulty ignoring “irrelevant” stimuli, both associated with ADHD, are also more common in people who display high levels of creativity (Zabelina et al., 2015, Zabelina et al., 2013), so there may be common features in the neurobiology of ADHD and creativity.

Beyond creativity, ADHD adults identified higher levels of energy, courage, adventurousness, and non-conformity as positive factors they associate with their ADHD (Holthe & Langvik, 2017, Sedgwick et al., 2018). There is also a higher-than-average rate of ADHD in populations of athletes, suggesting that some aspects of this neurotype support athletic engagement, like quick decision making and high energy (Han, 2019). In fact, Olympic athletes Simone Biles, Michael Phelps, and Molly Seidel all have ADHD. Other Icons with ADHD include musicians Solange Knowles, Henry Lau and engineer Dean Kamen, who invented the Segway and iBOT (Figure PD.12).

Causes of ADHD

Given that ADHD can present in a variety of ways, it makes sense that there are a variety of contributing factors. It appears that ADHD is about 74% heritable, with many genes making small contributions, but environmental factors can also have an influence. For example, ADHD is more likely in those born premature, and those with early childhood infection. This may be because premature birth and infection cause inflammation, which alters neuron and synapse development. Many of the genes associated with ADHD are also involved in the growth and activity of neurons and synapses, especially those that use the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine. Indeed, the most common drug therapies for ADHD are stimulants like methylphenidate, which target dopamine and norepinephrine systems (Nùñez-Jaramillo et al., 2021).

Stimulants were first prescribed in the 1930s to treat headaches, but they were more effective for helping some people to concentrate. Later, researchers discovered that stimulant medications increased dopamine activity in certain areas, so they started studying dopamine systems in people with ADHD (Lange et al., 2010). Now we know that some people with ADHD have less dopamine activity in the basal ganglia, the frontal lobes, and the circuits that connect the two. Working together, these areas are involved in motivation, guiding attention, and impulse control, using dopamine as a messenger, so this pattern is more associated with attentional and hyperactive traits (Chu et al., 2021) than with inattentive traits. Other people with ADHD have higher than average connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and a subcortical area called the basal ganglia. This area is involved in perceptions of reward, and heightened connectivity here is associated with more impulsivity (Nùñez-Jaramillo et al., 2021).

Treatment and Support

Because there are a variety of factors that can result in the development of ADHD, treatments must be personalised. As we learned earlier, people with ADHD who have less frontal lobe activity respond better to treatment with stimulants, with reduced hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. Commonly prescribed stimulants are amphetamine and related drugs including methylphenidate, which blocks reuptake dopamine and norepinephrine to increase their levels in the synapse, and atomoxetine, which only blocks reuptake of norepinephrine. This increased activity of dopamine supports increased activity in the frontal areas that are less active in some people with ADHD (Nùñez-Jaramillo et al., 2021). However, these drugs aren’t effective for everyone, and people taking them usually need other kinds of support.

There are also effective non-pharmacological therapies for people with ADHD, which aim to teach families and people with ADHD to manage stress and emotions, communicate effectively, and implement strategies to help maintain and direct attention. Some examples of this are Behavioural Parent Training, which teaches parents of children with ADHD how to support their children, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) which aims to alter maladaptive thought patterns, and Mindfulness training, which can help in the self-regulation of attention (Modest-Lowe et al., 2015).

ADHD and Exercise

Regular exercise can increase the effectiveness of ADHD drugs, possibly by boosting activity in the prefrontal cortex (Choi et al., 2015). Exercise also improves symptoms of depression and anxiety, especially in combination with psychotherapy, and may also be effective in preventing future depressive symptoms (Hu et al. 2020; Martinsen, 2008). Read this article about exercise intervention for ADHD from the Children and Adults with Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (CHADD) organisation, to learn more.

The Autism Spectrum

Min is sitting in class. The fluorescent lights buzz and flicker like strobe lights across their vision. It becomes harder to understand the professor’s words in the cloud of static, and they begin to panic. They need to go somewhere darker and quieter, but lectures aren’t recorded, and they have trouble interacting with strangers so they don’t know anyone to get notes from. They want to rock in their seat so they can calm down and self-regulate, but they’ve been told it’s disruptive. As Min leaves after class, someone speaks to them, but Min is so overwhelmed that they can’t understand, and it feels like there’s something stopping the words in their brain from getting to their mouth. Min puts a practiced “friendly” expression on their face, hoping it was appropriate for the social context. They get home just in time to start crying and rocking in the privacy of their room. They can’t think or stop, and they’re exhausted afterwards. As the term goes on it gets harder to be in class and by the end, Min struggles to speak and leave the house. They have to ask for extensions on their final projects.

Symptoms and Traits

“When you meet one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism”. Dr Stephen Mark Shore, an autistic professor of special education at Adelphi University in New York (De Ambrogi, 2024)

The term “autism” describes a range of neurotypes that share underlying patterns of activity and connectivity. For this reason, it’s referred to as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), acknowledging that autistic people can present in a variety of ways with many different needs. The quote by Dr. Shore above reminds us to not overgeneralise from one person with ASD to another.

In Canada, approximately 2% of children and youth aged 1 to 17 are diagnosed with autism, as indicated by the Public Health Agency of Canada’s analysis of the 2019 health survey data (Public Health Agency of Canada, n.d.; Autism Alliance of Canada, 2022). However, these estimates may not fully capture the true prevalence of autism due to variations in data collection methodologies and differences in diagnosis rates across regions. The prevalence of autism significantly varies across provinces and among different socio-economic groups, suggesting the potential for even higher rates than initially reported (Public Health Agency of Canada, n.d.).

Some autistic people refer to themselves as having “low support needs”, meaning that the impairment they experience requires relatively less support. Others refer to themselves as having “high support needs”, meaning that they need relatively more support to go about daily life. Min’s experience represents someone with lower support needs. Autistic people in these groups have the same kinds of traits, many of which can be categorised as differences in social communication and interaction with neurotypical people, or as restricted, repetitive behaviours. These two categories of traits come from the DSM-5, which is currently used in the diagnosis of ASD.

Social Communication and Interaction

There are 3 types of symptoms that may indicate differences in social communication and interaction (APA, 2013):

- Differences in or absence of social and emotional back and forth, like turn-taking in conversation or sharing interests and emotions.

- Differences in or absence of nonverbal communication behaviours such as eye contact, facial expression, gesture, and other body language.

- Difficulty understanding and performing according to neurotypical social expectations, and difficulty or a lack of interest in developing and maintaining relationships.

Due to differences in social behavior and processing, many autistic people have difficulty identifying lies and non-literal language (Williams et al., 2018; Pexman et al., 2010), and benefit from direct communication about social expectations. Non-verbal communication in autistic individuals can vary. Some autistic people avoid eye contact, possibly because the subcortical areas of their brains, particularly the amygdala, are more active during eye contact (Hadjikhani, 2017). However, other autistic individuals may have a tendency to stare. Some autistic individuals and advocates argue that traits like avoiding eye contact or staring should be seen as differences rather than impairments. They point out that autistic people often do not experience the same social difficulties, such as misunderstandings or discomfort, when interacting with other autistic individuals (Crompton et al., 2020; Davis & Crompton, 2021).

Restrictive and Repetitive Patterns of Behaviour

There are four types of symptoms that may indicate restrictive and repetitive patterns of behaviour (APA, 2013):

- Repetitive movements, speech or use of objects.

- Preference for sameness and anxiety in response to changes or unexpected events.

- Extremely focused or intense interests, including strong attachments to objects; preoccupation with specific subjects or activities.

- Hyperreactivity, an increased response to certain sensory stimuli, and/or hyporeactivity, a decreased reactivity to certain sensory stimuli.

Because individuals with ASD process sensory stimuli differently, some sensations can be more painful or more pleasurable than they would be for neurotypical people. This can lead to an insistence on sameness, as a way to avoid stimuli that is overwhelming and difficult to deal with (MacLennan, 2020). When sensory differences make sensations more pleasurable, autistic people may be motivated to engage with them repeatedly both because they are enjoyable, and to reduce anxiety. Often, these kinds of repetitive behaviours are called “stims” by autistic people, though non-autistic people also stim sometimes (e.g., tapping the foot or twirling the hair). Another common pattern of repeated behaviour for autistic people is the development of intense, long-lasting interests in particular subjects, often called special interests (Grove et al., 2018). Like people with ADHD, autistic people may be prone to hyperfocus, especially when engaging with a special interest.

Common Traits and Experiences

Shutdowns and Meltdowns

Shutdowns and meltdowns are well-known but under-researched experiences for many autistic people. Meltdowns are an externalisation or release of stress that overwhelms an autistic person’s coping mechanisms, often preceded by sensory overload (Phung et al., 2021, Schaber, 2014). Externalisation may involve screaming, stomping, sometimes self-injurious stimming and other similar behaviours that allow the autistic person to reduce internal tension.

Shutdowns are the internalised version of meltdowns, also occurring when the individual can’t deal with stress and sensory overload. Rather than releasing tension externally, the individual shuts down or dissociates to reduce their exposure to the sensory environment. Adults with autism report that this involves decreased sensation; for example, they may experience physical numbness and narrowing of vision. An autistic person experiencing shutdown may be unresponsive and exhausted (Phung et al., 2021, Schaber, 2014).

During meltdowns and shutdowns, autistic people report impaired cognitive and sensory processing, loss of communication skills, and less control over their body (Nason, 2019). Meltdowns and shutdowns are not intentional and generally can’t be stopped once they start. People experiencing meltdown should never be held down, as this practice has the potential to injure and in the worst cases can be fatal (Bartlett & Ellis, 2020, Vogel, 2014). Rather, care must be taken to help them escape triggering environments and reduce the amount of stimulation and stress they’re experiencing so they can recover (Myles & Southwick, 1999).

Autistic Masking and Burnout

Masking involves suppressing autistic traits and using a learned set of rules or scripts to blend in with neurotypical people. Not all autistic people can mask, and while masking may help some overcome certain social barriers, it’s described as tiring and anxiety provoking (Hull et al., 2017), and is associated with autistic burnout.

Autistic burnout involves long-term exhaustion, reduced cognitive function, loss of previously mastered skills, social withdrawal, and an increase in autistic traits (Higgins et al., 2021; Raymaker et al., 2020). One might lose the ability to perform facial expressions or use verbal language; sensory processing issues intensify; and the individual may need to spend less time socialising, speaking, and masking (Phung et al., 2021).

While unmasking may be beneficial for long-term health, it may also put people with ASD at increased risk of violence. Data from police reports indicates that 42% of people killed by police in Canada were in mental distress, and data from the US indicates that 33-50% of people killed by police were disabled (Nicholson & Marcoux, 2018; Perry & Carter-Long, 2016). In many of these cases, disabled people displaying non-violent distress or behaviour associated with their disability or neurotype were reported as acting suspicious and were unable to respond to law enforcement as expected, at which point police proceeded to use violent force.

This was the case for Elijah Mccain, who was reported because he “looked sketchy”. In fact, Elijah was harmlessly stimming by waving his arms, and wearing an open-faced ski mask to combat cold as a result of his chronic anemia. He had not committed any crime, but he was killed during the encounter because he was visibly distressed, and “tensed up” when restrained (Thompkin, 2020).

As in Elijah’s case, this risk is increased for those particularly affected by anti-Black or Indigenous racism, who are already more likely to be victims of police violence (Lett et al., 2020; Diamond & Hogue, 2021). In order to make it safe for all people with ASD to take care of themselves and unmask, systemic forms of oppression must also be addressed.

Non-Verbal Autism

Approximately 25-30% of autistic children don’t develop verbal language. Some may develop verbal language skills as they age, while others won’t. For years it was assumed that non-verbal autistic people couldn’t communicate or advocate for themselves, however, while some do have trouble understanding language, others have good comprehension even if they can’t speak themselves (Rapin et al., 2009). In these cases, they may need access to alternate forms of communication like picture cards or text-to-speech apps. Autistic people given Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) methods or technologies communicate significantly more and have better communication skills (Ganz et al., 2012). Forms of sign language are effective for many people on the spectrum and are helpful in improving outcomes for autistic children (Goldstein, 2002) and autistic people with intellectual disabilities. Because verbal language is commonly lost during burnouts and meltdowns, AAC can also be helpful for those who are able to speak most of the time.

More About Augmentative and Alternative Communication

Watch these videos on Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) to learn more. This video from Fairfax County Schools, outlines Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) devices and how they help give students a voice in their learning; this video from Louisiana AEM shows how to create your own AAC board at home.

Autistic Strengths

Autistic people demonstrate several perceptual advantages, including above average pitch perception, spatial reasoning and recognition of visual patterns (Soulières et al., 2011, Stevenson & Gernsbacher, 2013). For example, some autistic people are hyperlexic, meaning that they can read at a higher level than expected for their age, possibly because they have an enhanced ability to recognise the visual characteristics of words (Mottron, 2006). This superior processing for lower-level sensory information also results in superior memory abilities for some autistic people like Stephen Wiltshire, whose exceptional visual memory allows him to accurately illustrate entire cityscapes after a single flight across the skyline.

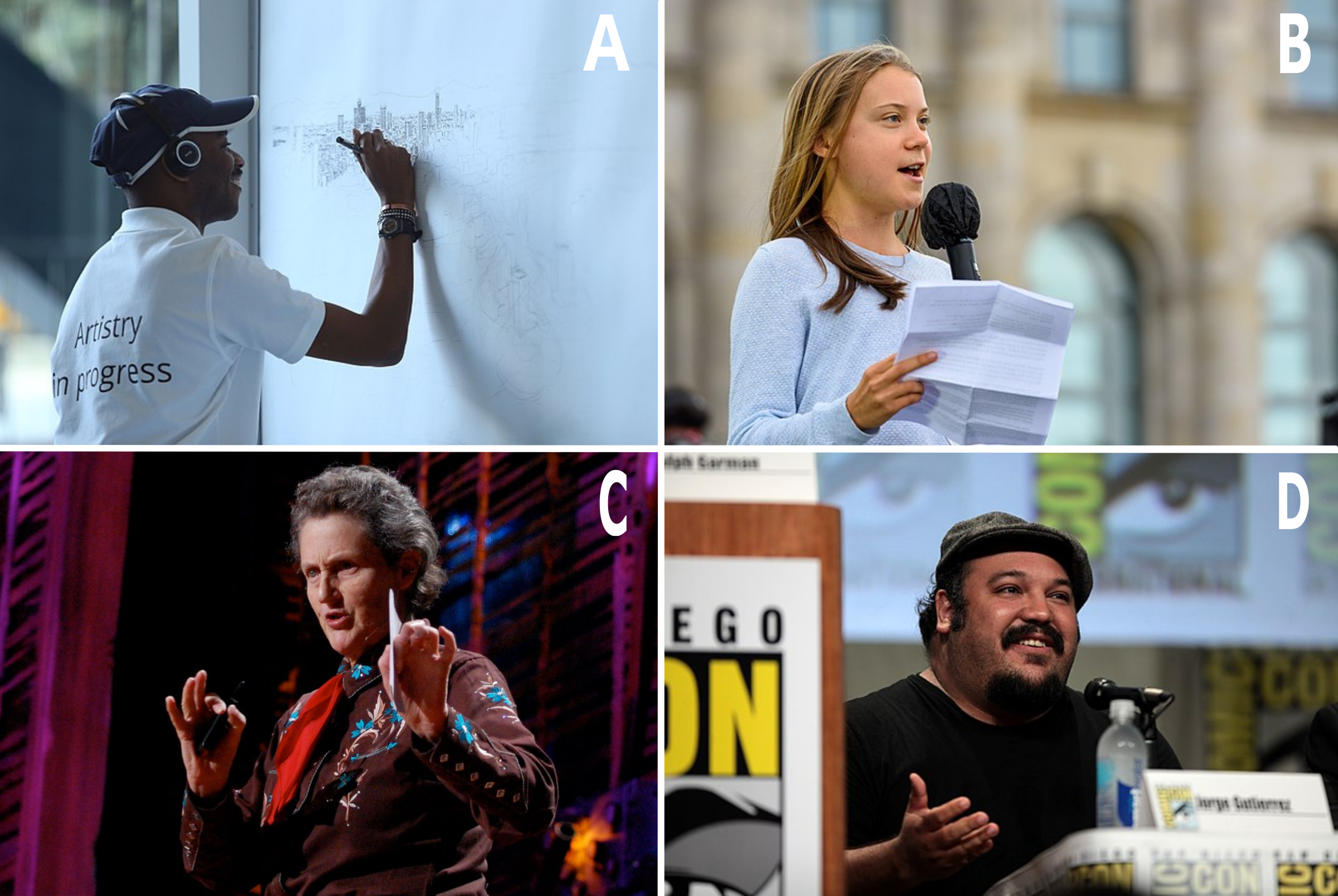

Many autistic people also demonstrate subtle differences in empathic processes and moral reasoning. For example, one study found that autistic people were less likely than neurotypical people to compromise their moral beliefs for personal gain, even when they were unobserved (Hu et al., 2020), and another found that autistic people were less likely than neurotypical people to show bias towards members of their own group (Uono et al., 2021). Other autistic icons include animal behaviour consultant Temple Grandin, climate activist Greta Thunberg, artist Stephen Wiltshire, and multidisciplinary filmmaker Jorge R. Gutiérrez, who co-wrote and directed The Book of Life (Figure PD.13).

Causes of Autism

The strongest evidence suggests that autism is mostly heritable. One study involving 2 million children across multiple countries found that genetics accounted for almost 80% of one’s likelihood of being diagnosed with autism (Bai et al., 2019). Relatives of people with autism also have higher rates of related genetic syndromes and autism-like traits (Chaste & Leboyer, 2022). Hundreds of genes have been identified as making some contribution, and many are involved in neural development, neurotransmitter function, and synapse function (Hodges et al., 2020). Scientists have found that many different genes play a role in autism. These genes are important for how the brain develops, how brain chemicals work, and how brain cells communicate with each other (Hodges et al., 2020). One of these genes is called SHANK3. It helps with brain cell connections that use a chemical called glutamate. Many autistic people have higher levels of glutamate in parts of their brain that are involved in movement and touch. This difference in glutamate levels is linked to unusual ways of processing sensory information.

Evidence also suggests that some of these genes affect the balance of certain brain chemicals (Al-Otaish et al., 2018; Cochran, 2015; He et al., 2021). For example, some autistic people have higher levels of excitatory neurotransmitters (which stimulate brain activity) and lower levels of inhibitory neurotransmitters (which calm brain activity) compared to neurotypical people. This difference is linked to the way autistic individuals process social information and sensory input.

Additionally, differences have been found in the growth patterns of grey and white matter in specific areas of the brain, particularly in the cerebellum, which is connected to the frontal and parietal lobes (D’Mello et al., 2015). These differences are associated with social traits and repetitive behaviors seen in autism. As expected, autistic individuals also show more activity in primary sensory areas of the brain, which relates to their unique sensory processing (Samson, 2011).

Researchers’ lie leads to decades of harm as parents believe “medical fake news” and avoid vaccines for their children

There is no support for the theory that vaccines or mercury contribute to the development of autism (DeStefano, 2007). A comprehensive meta-analysis involving over 1.25 million children found no relationship between vaccination and autism or autism spectrum disorders (ASD). This includes no link between autism and MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), thimerosal, or mercury in vaccines. (Taylor, Swerdfeger, & Eslick, 2014).

A pseudo (fake) study by Dr. Andrew Wakefield and colleagues (Wakefield, et al., 1998), which initially claimed a link between the MMR vaccine and autism, was later discredited due to ethical, medical, and scientific misconduct. Investigations revealed that the data presented were fraudulent, making this one of the most damaging medical hoaxes of the last 100 years. (Flaherty, 2011; Godlee et al., 2011).

Some people continue to believe in and pass on this medical fake news about vaccines and ASD. This research wrong-doing highlights how important it is that people are able to trust the medical world. This shocking story of medical research misconduct reminds us of the critical need for strict, ethical research and clear communication. Moving forward, it’s crucial that we adopt strategies that clearly explain that there is widespread scientific agreement on the safety and importance of vaccines. This involves not only direct and honest discussions but also teamwork among doctors, educators, and public health advocates to rebuild trust and support people in making informed choices about vaccinations.

Support for Autistic People and Caregivers

Historically, many techniques have aimed to suppress autistic traits rather than help autistic people to overcome disadvantages and meet their specific needs. For example, harmful applied behavioural analysis (ABA) focuses on punishing autistic behaviours and coping mechanisms like stimming. ABA has been identified as an abusive therapy by the Autistic community (ASAN, 2021; Sandoval-Norton & Shkedy, 2019).

Many adults with ASD report that punishment for stimming negatively affects their self-confidence and sense of control over their bodies (Kapp et al., 2019, Gardiner, 2017). Stimming indicates that an autistic person may be coping with something overwhelming, so it’s better to help them address that if they need assistance. This is especially important for autistic children and non-verbal people with autism, who experience barriers in communicating their needs (Sandoval-Norton & Shkedy, 2019). If someone stims when they are in rooms with yellow light, the light may be overwhelming and could be changed to make them more comfortable. Alternatively, if they can tolerate wearing glasses, coloured lenses might help.

If you don’t have these kinds of sensitivities, consider how it feels to try and walk with a rock in your shoe. If you can’t take the rock out, it might become the only thing you can think about, making it increasingly difficult to engage with your environment. However, if you take the rock out, you can recover and re-engage. These simple strategies can greatly impact an autistic person’s comfort and functioning.

Some autistic people find Social Skills Training (SST) helpful. Others argue that SST teaches neurodivergent people to mask and treat social interaction like math problems rather than engaging authentically and learning to identify and communicate their feelings (Roberts, 2022). It is argued that SST devalues neurodivergent social skills and, as we learned earlier, autistic people don’t experience the same social issues when interacting with each other (Roberts, 2021; Davis & Crompton, 2021). SST may enhance an autistic person’s ability to mask and succeed in some domains, but this may also come at a cost to their own well-being. It is possible that it wouldn’t be necessary if society were more accessible to them.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

Augmentative means adding to or enhancing communication, not to be confused with “argumentative,” which means having a tendency to argue. Examples of augmentative methods are:

- Using pictures: A person points to pictures on a communication board to express what they want or need.

- Speech-generating devices: A device that speaks out loud when a person selects words or symbols.

Alternative means providing another way to communicate when someone cannot use spoken words. Examples of alternative methods of communication are:

- Sign language: Using hand signs to communicate instead of spoken words.

- Text-to-speech apps: An app that converts typed text into spoken words for someone who cannot speak.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) helps people with communication difficulties express themselves more effectively.

Given the diversity of people on the spectrum, appropriate supports and accommodations vary widely. Some have already been discussed. For example, Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) can be helpful for those struggling with verbal communication, and alterations to the environment can help with sensory issues. Autistic people may also benefit from occupational therapy to learn skills that can help them live more independently and meet their goals. For example, many autistic people have issues with coordination, and benefit from physical training to develop fine motor skills. Occupational therapists can also help identify autistic strengths and recommend modifications to activities and environments that allow autistic people to perform at their full capacity.

People with ASD and caregivers also experience higher rates of anxiety and depression than neurotypical people, in part because of social stigma and a lack of accessibility. There is evidence that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and mindfulness training are effective for treating anxiety and depression in autistic people and caregivers (Ridderinkhof et al., 2017), and that mindfulness training may also have a positive impact on emotional and sensory regulation (White et al., 2018).

Similarities and Differences: Diagnostic Bias

Classically, ADHD and autism are considered conditions that affect white, cisgender AMAB children (assigned male at birth). Some estimates suggest that there are four times as many AMAB children as AFAB (assigned female at birth) children diagnosed with these conditions (Ramtekkar, 2010). Recently however, adult diagnosis has become more common, and new data indicates that this gender difference shrinks with age (Rutherford et al., 2016).

On average, AFAB (assigned female at birth) people are more likely to be misdiagnosed or diagnosed later in life (Adamis, 2022; Dworzynski et al., 2012). This may result from a lack of awareness about different presentations of autism and ADHD.

For example, assigned female at birth (AFAB) people with ADHD are more likely to have Primary Inattentive ADHD (ADHD-PI) symptoms, which means they mainly have trouble paying attention and are less likely to be hyperactive. AFAB autistic people also tend to show fewer social traits (like difficulty with social interactions) and more sensory traits (such as being very sensitive to sounds, lights, or textures) than AMAB (assigned male at birth) children (Lai et al., 2011; Adamis, 2022).

There is likely also a gender bias, as AMAB (assigned male at birth) children are more likely to be referred for diagnosis than AFAB (assigned female at birth) children with equivalent traits (Scuitto et al., 2004). On average AFAB autistic children with official diagnosis also have higher levels of autistic traits than AMAB children, suggesting that AFAB children need to experience more impairment to be diagnosed (Rutherford et al., 2016).

Interestingly some data indicates that there are higher than average rates of transgender or gender-diverse identity in neurodiverse populations. For example, Warrier et al. (2020) found that 24% of gender-diverse people in their sample had autism, as compared to only 5% of cisgender people.

Evidence suggests there is also a diagnostic bias against people of colour, particularly Black people, as Black autistic children are 2 times more likely to be misdiagnosed with conduct disorder than white autistic children with the same traits (Mandell et al., 2006; Fombonne & Zuckerman, 2022). Similarly, Black children are 5.1 times more likely to be diagnosed with adjustment disorder and 2.4 times more likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorder, while white children with the same traits are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD (Ballentine, 2019). No difference has been found in levels of ADHD or autism-related traits between these groups. If children of colour and non-Hispanic white children display the same rates of ADHD and autism-like behaviours but are diagnosed differently, then it’s likely that race-based bias is affecting the way they are being perceived by diagnosticians (Fadus et al., 2019).

Similarities and Differences: Sensory Processing

People with ADHD and/or autism have differences in sensory processing that affect the way they react to stimuli. For example, some are hypo-reactive to interoceptive stimuli, which are sensations that come from inside the body, like hunger pains or the feeling of a full bladder. If you have trouble with interoception, you may struggle to identify sensations like pain or hunger, which can cause distress as you may not know how to address unpleasant sensory experiences. Many autistic people also have alexithymia, meaning that they have trouble sensing and identifying their own emotions and the emotions of others.

Others are hyper-reactive to certain stimuli, like sound, light, and physical sensation. These people may need to wear tinted lenses or ear plugs and may avoid certain kinds of material for clothing in order to avoid becoming overstimulated.

It is even possible to be both under and over responsive to a kind of stimuli, and to switch between the two (Wigham, 2014). Some sensory differences can also result in positive experiences. For example, a heightened response to sound can enhance enjoyment of music, while differences in somatosensory processing might make it feel really good or soothing to rock back and forth. Everyone engages in this kind of sensory seeking behaviour sometimes, but autistic people may be motivated to do this more often, both for enjoyment and for self-care.

Sensory differences influence cognitive and behavioural differences as well. For example, someone with ADHD may have trouble maintaining attention because they are hyper-reactive to sound and are distracted by noises in the environment. This hyper-reactivity could result from a reduced ability to filter stimuli as evidenced by neuroimaging studies, which have found higher activity in lower-level sensory areas like the superior and inferior colliculi, which help the body direct itself toward visual and auditory stimuli (Panagiotidi et al., 2020).

Alternatively, people with ADHD may appear inattentive because they have low sensitivity to sound and attempts to get their attention haven’t registered (Shimizu et al., 2014). One theory suggests that some people with ADHD are under-stimulated at baseline, resulting in hyper-activity and sensation-seeking behaviours to self-generate stimulation. There is evidence that increased environmental simulation can enhance performance for some people with ADHD. For example, Söderlund et al. (2007) found that subjects with ADHD did better on cognitive tasks with white noise in the background. Remember also that stimulant medications prescribed to people with ADHD act by increasing neural stimulation in areas that are under-active (Ogrim et al., 2013).

In people with autism, sensory reactivity can predict stimming, insistence on sameness, and special interests (Kapp et al., 2019). Like people with ADHD, people with autism have trouble ignoring certain stimuli. This might be because autistic people take longer to habituate, meaning that their nervous systems keep reacting to unchanging stimuli longer than the nervous systems of neurotypical people.

Autistic people also seem to filter and group stimuli less than neurotypical people, possibly resulting from differences in association areas, which combine information from different senses. Association areas are parts of the brain that integrate information from various senses like sight and sound. Some evidence suggests that in autistic people, these differences result in better processing for individual stimuli than for groups (Proff et al., 2022; Quintin, 2019). This means autistic individuals might focus more effectively on single pieces of information rather than on collections of information. This is a tendency toward local processing, similar to that of people with ADHD. (Local processing refers to paying more attention to small details rather than the overall picture.) For those with ADHD, however, this might result from difficulty shifting attention from one detail to another (Gargaro et al., 2015; Cardillo et al., 2020). In other words, people with ADHD may struggle to move their focus from one piece of information to another.

Image Attributions

Figure PD.10. Figure PY.10 by Max Dysart as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PD.11. Figure PY.11 by White, 2018 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PD.12. (a) Solange Knowles (Adapted from work by Neon Tommy, licensed under CC BY 2.0) (b) Henry Lau (Adapted from work by NewsInstar, licensed under CC BY 3.0) (c) Dean Kamen (Adapted from work by Greg Heartsfield, licensed under CC BY 2.0) (d) Simone Biles (Adapted from work by Agência Brasil Fotografias, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Figure PD.13. (a) Stephen Wiltshire (Adapted from work by Gobierno CDMX, licensed under CC0 1.0). (b) Greta Thunberg (adapted from work by Stefan Müller, licensed under CC BY 2.0 ). (c) Temple Grandin (adapted from work by Red Maxwell, licensed under CC BY 2.0 ). (d) Jorge R. Gutiérrez (adapted from work by Gage Skidmore, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0).

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).